Rugby union

Rugby union, commonly known simply as rugby, is a close-contact team sport that originated at Rugby School in the first half of the 19th century. One of the two codes of rugby football, it is based on running with the ball in hand. In its most common form, a game is played between two teams of 15 players each, using an oval-shaped ball on a rectangular field called a pitch. The field has H-shaped goalposts at both ends.

South African Victor Matfield takes a line-out against New Zealand in 2006 | |

| Highest governing body | World Rugby |

|---|---|

| Nicknames | |

| First played | 19th century, England, United Kingdom |

| Registered players | 6,600,000[3][nb 1] |

| Clubs | 180,630 |

| Characteristics | |

| Contact | Full |

| Team members | 15 (with up to 8 substitutes) |

| Mixed-sex | Separate competitions |

| Type |

|

| Equipment |

|

| Venue | Rugby field |

| Presence | |

| Country or region | Worldwide (most popular in certain European and Commonwealth countries) |

| Olympic | Part of the Summer Olympic programme in 1900, 1908, 1920 and 1924 Rugby sevens included in 2016 and 2020 |

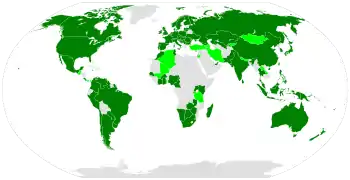

Rugby union is a popular sport around the world, played by people of all genders and ages. In 2014, there were more than 6 million people playing worldwide, of whom 2.36 million were registered players. World Rugby, previously called the International Rugby Football Board (IRFB) and the International Rugby Board (IRB), has been the governing body for rugby union since 1886, and currently has 101 countries as full members and 18 associate members.

In 1845, the first laws were written by pupils at Rugby School; other significant events in the early development of rugby include the decision by Blackheath F.C. to leave The Football Association in 1863 and, in 1895, the split between rugby union and rugby league. Historically rugby union was an amateur sport, but in 1995 formal restrictions on payments to players were removed, making the game openly professional at the highest level for the first time.[4]

Rugby union spread from the Home Nations of Great Britain and Ireland, with other early exponents of the sport including Australia, New Zealand, South Africa and France. The sport is followed primarily in the British Isles, France, Georgia, Oceania, Southern Africa, Argentina, and to a lesser extent Italy, Uruguay, the United States,[5][6][7] Canada, and Japan, its growth occurring during the expansion of the British Empire and through French proponents (Rugby Europe) in Europe. Countries that have adopted rugby union as their de facto national sport include Fiji, Georgia, Madagascar,[8] New Zealand, Samoa, Tonga, and Wales.

International matches have taken place since 1871 when the first game was played between Scotland and England at Raeburn Place in Edinburgh. The Rugby World Cup, first held in 1987, is held every four years. The Six Nations Championship in Europe and The Rugby Championship in the Southern Hemisphere are other important international competitions that are held annually.

National club and provincial competitions include the Premiership in England, the Top 14 in France, the Bunnings NPC in New Zealand, the League One in Japan and the Currie Cup in South Africa. Other transnational club competitions include the United Rugby Championship of club teams from Ireland, Italy, Scotland, South Africa and Wales, European Rugby Champions Cup in Europe, and Super Rugby Pacific in Australia, New Zealand and the Pacific Islands.

History

Rugby football stems from the form of the game played at Rugby School, which former pupils then introduced to their universities.

Former Rugby School student Albert Pell is credited with having formed the first "football" team while a student at Cambridge University.[9] Major private schools each used different rules during this early period, with former pupils from Rugby and Eton attempting to carry their preferred rules through to their universities.[10] A significant event in the early development of rugby football was the production of a written set of rules at Rugby School in 1845,[11][12] followed by the Cambridge Rules that were drawn up in 1848.[13]

Formed in 1863, the national governing body The Football Association (FA) began codifying a set of universal football rules. These new rules specifically banned players from running with the ball in hand and also disallowed hacking (kicking players in the shins), both of which were legal and common tactics under the Rugby School's rules of the sport. In protest at the imposition of the new rules, the Blackheath Club left the FA[14][15] followed by several other clubs that also favoured the "Rugby Rules". Although these clubs decided to ban hacking soon afterwards, the split was permanent, and the FA's codified rules became known as "association football" whilst the clubs that had favoured the Rugby Rules formed the Rugby Football Union in 1871,[14] and their code became known as "rugby football".

In 1895, there was a major schism within rugby football in England in which numerous clubs from Northern England resigned from the RFU over the issue of reimbursing players for time lost from their workplaces. The split highlighted the social and class divisions in the sport in England. Although the rules of the game were not a factor in the split, the breakaway teams subsequently adopted some rule changes and this became the separate code of "rugby league". The RFU's code thereafter took on the name "rugby union" to differentiate it from rugby league,[16] but both versions of the sport are known simply as "rugby" throughout most of the world.[17]

First internationals

The first rugby football international was played on 27 March 1871 between Scotland and England in Edinburgh. Scotland won the game 1–0.[14][18] By 1881 both Ireland and Wales had representative teams and in 1883 the first international competition, the Home Nations Championship had begun. 1883 is also the year of the first rugby sevens tournament, the Melrose Sevens,[19] which is still held annually.

Two important overseas tours took place in 1888: a British Isles team visited Australia and New Zealand—although a private venture, it laid the foundations for future British and Irish Lions tours;[20] and the 1888–89 New Zealand Native football team brought the first overseas team to British spectators.[21]

During the early history of rugby union, a time before commercial air travel, teams from different continents rarely met. The first two notable tours both took place in 1888—the British Isles team touring New Zealand and Australia,[22] followed by the New Zealand team touring Europe.[23] Traditionally the most prestigious tours were the Southern Hemisphere countries of Australia, New Zealand and South Africa making a tour of a Northern Hemisphere, and the return tours made by a joint British and Irish team.[24] Tours would last for months, due to long traveling times and the number of games undertaken; the 1888 New Zealand team began their tour in Hawkes Bay in June and did not complete their schedule until August 1889, having played 107 rugby matches.[25] Touring international sides would play Test matches against international opponents, including national, club and county sides in the case of Northern Hemisphere rugby, or provincial/state sides in the case of Southern Hemisphere rugby.[22][26]

Between 1905 and 1908, all three major Southern Hemisphere rugby countries sent their first touring teams to the Northern Hemisphere: New Zealand in 1905, followed by South Africa in 1906 and Australia in 1908. All three teams brought new styles of play, fitness levels and tactics,[27] and were far more successful than critics had expected.[28]

The New Zealand 1905 touring team performed a haka before each match, leading Welsh Rugby Union administrator Tom Williams to suggest that Wales player Teddy Morgan lead the crowd in singing the Welsh National Anthem, Hen Wlad Fy Nhadau, as a response. After Morgan began singing, the crowd joined in: the first time a national anthem was sung at the start of a sporting event.[29][nb 2] In 1905 France played England in its first international match.[27]

Rugby union was included as an event in the Olympic Games four times during the early 20th century. No international rugby games and union-sponsored club matches were played during the First World War, but competitions continued through service teams such as the New Zealand Army team.[31] During the Second World War no international matches were played by most countries, though Italy, Germany and Romania played a limited number of games,[32][33][34] and Cambridge and Oxford continued their annual University Match.[35]

The first officially sanctioned international rugby sevens tournament took place in 1973 at Murrayfield, one of Scotland's biggest stadiums, as part of the Scottish Rugby Union centenary celebrations.[36]

World Cup and professionalism

In 1987 the first Rugby World Cup was held in Australia and New Zealand, and the inaugural winners were New Zealand. The first World Cup Sevens tournament was held at Murrayfield in 1993. Rugby Sevens was introduced into the Commonwealth Games in 1998 and was added to the Olympic Games of 2016.[37] Both men and women's Sevens took place at the 2020 Olympic Games in Tokyo.[38]

Rugby union was an amateur sport until the IRB declared the game "open" in August 1995 (shortly after the completion of the 1995 World Cup), removing restrictions on payments to players.[39][40] However, the pre-1995 period of rugby union was marked by frequent accusations of "shamateurism",[41] including an investigation in Britain by a House of Commons Select committee in early 1995.[42][43] Following the introduction of professionalism trans-national club competitions were started, with the Heineken Cup in the Northern Hemisphere and Super Rugby in the Southern Hemisphere.[44][45]

The Tri Nations, an annual international tournament involving Australia, New Zealand and South Africa, kicked off in 1996.[45] In 2012, this competition was extended to include Argentina, a country whose impressive performances in international games (especially finishing in third place in the 2007 Rugby World Cup) was deemed to merit inclusion in the competition. As a result of the expansion to four teams, the tournament was renamed The Rugby Championship.[46]

Teams and positions

Each team starts the match with 15 players on the field and seven or eight substitutes.[47] Players in a team are divided into eight forwards (two more than in rugby league) and seven backs.[48]

Forwards

The main responsibilities of the forward players are to gain and retain possession of the ball. Forwards play a vital role in tackling and rucking opposing players.[49] Players in these positions are generally bigger and stronger and take part in the scrum and line-out.[49] The forwards are often collectively referred to as the 'pack', especially when in the scrum formation.[50]

Front row

The front row consists of three players: two props (the loosehead prop and the tighthead prop) and the hooker. The role of the two props is to support the hooker during scrums, to provide support for the jumpers during line-outs and to provide strength and power in rucks and mauls. The third position in the front row is the hooker. The hooker is a key position in attacking and defensive play and is responsible for winning the ball in the scrum. Hookers normally throw the ball in at line-outs.[48][51]

Second row

The second row consists of two locks or lock forwards. Locks are usually the tallest players in the team, and specialise as line-out jumpers.[48] The main role of the lock in line-outs is to make a standing jump, often supported by the other forwards, to either collect the thrown ball or ensure the ball comes down on their side. Locks also have an important role in the scrum, binding directly behind the three front row players and providing forward drive.[48]

entering the scrum

Back row

The back row, not to be confused with 'Backs', is the third and final row of the forward positions, who are often referred to as the loose forwards.[50] The three positions in the back row are the two flankers and the number 8. The two flanker positions called the blindside flanker and openside flanker, are the final row in the scrum. They are usually the most mobile forwards in the game. Their main role is to win possession through 'turn overs'.[48] The number 8 packs down between the two locks at the back of the scrum. The role of the number 8 in the scrum is to control the ball after it has been heeled back from the front of the pack, and the position provides a link between the forwards and backs during attacking phases. [52]

Backs

The role of the backs is to create and convert point-scoring opportunities. They are generally smaller, faster and more agile than the forwards.[49] Another distinction between the backs and the forwards is that the backs are expected to have superior kicking and ball-handling skills, especially the fly-half, scrum-half, and full-back.[49]

Half-backs

The half-backs consist of two positions, the scrum-half and the fly-half also known in the Southern Hemisphere as, half-back and first five-eighth respectively. The fly-half is crucial to a team's game plan, orchestrating the team's performance.[52] They are usually the first to receive the ball from the scrum-half following a breakdown, lineout, or scrum, and need to be decisive with what actions to take and be effective at communicating with the outside backs.[52] Many fly-halves are also their team's goal kickers. The scrum-half is the link between the forwards and the backs.[52] They receive the ball from the lineout and remove the ball from the back of the scrum, usually passing it to the fly-half.[53] They also feed the scrum and sometimes have to act as a fourth loose forward.[54]

Three-quarters

There are four three quarter positions: two centres (inside and outside) and two wings (left and right), the inside centre is commonly referred to as the second five-eighth in the Southern Hemisphere. The centres will attempt to tackle attacking players; whilst in attack, they should employ speed and strength to breach opposition defences.[52] The wings are generally positioned on the outside of the backline. Their primary function is to finish off moves and score tries.[55] Wings are usually the fastest players in the team and are elusive runners who use their speed to avoid tackles.[56]

Full-back

The full-back is normally positioned several metres behind the back line. They often field opposition kicks and are usually the last line of defence should an opponent break through the back line.[52] Two of the most important attributes of a good full-back are dependable catching skills and a good kicking game.[57]

Laws and gameplay

Scoring

Rugby union is played between two teams – the one that scores more points wins the game. Points can be scored in several ways: a try, scored by grounding the ball in the in-goal area (between the goal line and the dead-ball line), is worth 5 points and a subsequent conversion kick scores 2 points; a successful penalty kick or a drop goal each score 3 points.[58] The values of each of these scoring methods have been changed over the years.[59]

Playing field

According to World Rugby's Laws of the Game,[60] a typical rugby ground, formally known as the "playing enclosure", is formed by two major zones:

- The "playing area", which includes the "field of play" and the two "in-goals", and

- The "perimeter area", a clear space, free of obstructions such as fences and other objects which could pose a danger to players and officials (but not including marker flags, which are typically of soft construction).

The referee (and their assistants) generally have full authority and responsibility for all players and other officials inside the playing enclosure. Fences or ropes (particularly at amateur clubs) are generally used to mark the extent of this area, although in modern stadia this may include the entire arena floor or other designated space.

The Laws, above all, require that the playing enclosure's surface be safe, whilst also permitting grass, sand, clay, snow or conforming artificial turf to be used; the surface would generally be uniform across both the playing area and perimeter area, although depending on how large the perimeter is, other surfaces such as dirt, artificial turf, etc. may be used outside of a "sliding" perimeter from the bounds of the playing area.

Playing area

For the most part, the "playing area" is where the majority of play occurs. The ball is generally considered live whilst in this area, so long as players do not infringe, with special rules applied to specific zones of the playing area.

The playing area consists of:

- The 'field of play", bounded by (but not including) the sidelines and goal-lines, and

- One "in-goal" area at each end of the field, each bounded by, but not including, the extensions two parallel sidelines (known in this context as the "touch in-goal" lines) and the dead-ball line, and its other bound being the goal line (or "try line") which is included as part of the "in-goal" area.

Field of play

A typical "field of play" is generally 100 metres long by 68–70 metres wide for senior rugby, depending on the specific requirements of each ground. The Laws require the field of play to be between 94 metres (103 yards) and 100 metres (109 yards) long, with a width of between 68 metres (75 yards) and 70 metres (77 yards).

As other football codes, such as association football and rugby league, have specified a preferred or standard 68 metre width, this is often used unless a ground has been specifically designed to accommodate a 70-metre rugby field. 100 metres is the typical length, with a line (see below) often marked at halfway with "50" on it, representing 50 metres from each goal line. The variations have been allowed in the Laws, possibly to accommodate older grounds (perhaps even pre-metrification when yards and feet were specified) and developing nations.

Other lines and markings

The field of play is divided by a solid "halfway" line, drawn perpendicular to the sidelines at their midpoint. A 0.5m line is marked perpendicular to the halfway lines at its midpoint, designating the spot where the kickoffs shall be taken. The areas between each goal line and the halfway line are known as "halves" as in other football codes.

A pair of solid lines are also drawn perpendicular to the sidelines, 22 metres (formerly 25 yards) from each end of the field of play and called the 22-metre lines, or "22"s. An area at each end, also known as the "22", is bounded by, but does not include, the sidelines, goal line and 22-metre line. In this area, a defensive player who cleanly catches a ball kicked by the other team, without the ball having already touched the ground after the kick, is entitled to claim a free kick, or "mark".

Additional broken or dashed lines (of 5 metre dash lengths, according to the Laws) are drawn in each half or on each side of, the field, each with specific purposes under the Laws:

- "10-metre" lines: Dashed lines 10 metres either side of, and parallel to, the halfway line, designating the minimum distance a receiving team must retreat when receiving a kick-off, and the minimum distance a kick-off must travel to be legal. Equivalent to the 40-metre lines in rugby league but generally marked differently.

- "5-metre" lines: Dashed lines 5 metres into the field of play, parallel to each goal line. Scrums can be packed no nearer to each goal line than this line, and referees will often penalise scrum and ruck infringements in this area more harshly as defending sides will often try to stifle the attacking side's breakdown play.

- "Tram tracks/tramlines": Unnamed in the Laws and sometimes also referred to, confusingly, as the "5-metre" and "15-metre" lines, these two pairs of dashed lines are drawn parallel to each sideline, 5 metres and 15 metres, respectively, into the field of play from the nearer sideline, terminating at each of their respective ends' 5-metre line (parallel and adjacent to the goal line). The area between these lines are where players must stand when contesting a lineout throw.

- Additionally, the area between the two perpendicular sets of "5-metre" lines (i.e. 5 metres from each sideline and 5 metres from each goal line) is designated the "scrum zone". Where an offence occurs outside this area and the non-infringing side wishes to pack a scrum, the mark of the scrum will be moved into the zone by the referee.

Generally, points where the dashed lines intersect other lines will be marked with a "T" or cross shape, although the extensions of dashed lines are generally not drawn within 5 metres of the goal lines or sidelines, to allow a clear demarcation of the field of play's boundaries.

The Laws require the playing area to be rectangular in shape, however variations may be permitted with the approval of relevant unions. A notable example is Chatswood Oval in Sydney, Australia, an elliptically shaped cricket ground which is the home of Gordon rugby club, that has curved dead-ball lines to maximise the available in-goal space.

Where multiple sports share a field (e.g. a rugby league and a rugby union club sharing one field), lines may be overlaid on top of each other, sometimes in different colours. However, particularly for television, rugby union line markings are generally painted white. Some exceptions include the Wallabies (Australia's national team) who often have yellow markings. Local clubs may use black, yellow, or other colours on grass, with other surfaces possibly requiring different marking techniques.

Unlike association football, where on-field advertising is strictly forbidden in the laws,[61] World Rugby allows sponsors logos to be painted on the playing surface. This is another way in which clubs can make money in the professional era and is also often used by host nations, professional leagues and tournaments as additional revenue streams, particularly when games are broadcast. In recent years, augmented reality technology has been used to replace painting to protect the surface or save costs on painting fields, producing a similar effect for broadcast albeit sometimes with poorer results.[62]

In-goal areas

The in-goal areas sit behind the goal lines, equivalent to American football's "end zones". The in-goal areas must be between 6 metres (7 yards) and 22 metres (25 yards) deep and cover the full width of the field. A ball grounded in this area by an attacking player will generally result in a try being awarded, unless there has been a previous infringement or the player has gone out-of-bounds whilst in possession of the ball.

Perimeter area

The perimeter area is considered "out-of-bounds" for the ball and the players, normally resulting in the non-infringing team receiving possession of the ball at a restart. The perimeter area can be divided into two areas:

- "Touch": The perimeter area beyond the sidelines of the playing area, but between the goal lines.

- "Touch-in-goal": The perimeter areas behind each goal line outside of the playing area. Some may refer to a ball which crosses the dead-ball lines as "dead", rather than touch-in-goal.

For the purposes of determining if a ball is "out-of-bounds" (i.e. has left the playing area), the perimeter area extends indefinitely away from the playing area.

When a ball or player goes into touch, a lineout throw is generally awarded to the opposition at the spot on the sideline where they left the field. Exceptions include a kick out "on the full" (i.e. the ball did not land in the field-of-play before going into touch) in which case the lineout would still take place on the sideline but back in line with where the ball was kicked, or when a team takes a free kick from a penalty where they would retain the right to throw-in.

The perimeter area should be clear and free of obstructions and heavy, solid objects which could pose a danger to players for at least 5 metres from the playing area, according to the Laws. Players often leave the playing area whether accidentally or due to being forced off of the field, sometimes sliding or needing to slow down from a sprint. Many venues at elite levels leave larger spaces around the field to accommodate fitter and faster (or heavier) players. Fixed cameras on tripods and advertising hoardings are often the main culprits for injuring players in the perimeter area.

Flag posts

Also required in the perimeter area are a set of 14 flag posts, each with a minimum height of 1.2 metres, marking the intersections of certain lines or other nominated distances. These are generally a plastic pole on a spring loaded or otherwise soft base, sometimes with a flag on top, covered in foam padding. Others may be moulded plastic or disposable cardboard. At lower levels, these flags may not be used, but are still specified in the Laws. Flags are placed as follows:

- One flag post at each intersection of the touch-in-goal lines and the goal-lines (4 flags total)

- One flag post at each intersection of the touch-in-goal lines and the dead-ball lines (4 flags total)

- One flag post positioned 2 metres outside of both of the sidelines, in line with both of the 22-metre lines (4 flags total)

- One flag post positioned 2 metres outside of both of the sidelines, in line with the halfway line (2 flags total)

Goalposts

Rugby goalposts are H-shaped and are situated in the middle of the goal lines at each end of the field. They consist of two vertical poles (known as "uprights"), generally made of steel or other metal but sometimes wood or a plastic, 5.6 metres (6.1 yd) apart, connected by a horizontal "crossbar" 3 metres (3.3 yd) above the ground. The minimum height for posts' uprights is 3.4 metres (3.7 yd),[63] with taller posts generally seen. The bottom parts of each upright are generally wrapped in purpose-made padding to protect players from injury when coming into contact with the posts and creating another opportunity for sponsors. If an attacking player grounds the ball onto the base of the upright or post padding, a try will be awarded as the base of the upright is considered in-goal.

Match structure

At the beginning of the game, the captains and the referee toss a coin to decide which team will kick off first. Play then starts with a dropkick, with the players chasing the ball into the opposition's territory, and the other side trying to retrieve the ball and advance it. The dropkick must make contact with the ground before kicked. If the ball does not reach the opponent's 10-metre (11-yard) line 10 meters away, the opposing team has two choices: to have the ball kicked off again, or to have a scrum at the centre of the half-way line.[64] If the player with the ball is tackled, frequently a ruck will result.[65]

Games are divided into 40-minute halves, with an intermission of not more than 15 minutes in the middle.[66] The sides exchange ends of the field after the half-time break.[66] Stoppages for injury or to allow the referee to take disciplinary action do not count as part of the playing time, so that the elapsed time is usually longer than 80 minutes.[66] The referee is responsible for keeping time, even when—as in many professional tournaments—he is assisted by an official time-keeper.[66] If time expires while the ball is in play, the game continues until the ball is "dead", and only then will the referee blow the whistle to signal half-time or full-time; but if the referee awards a penalty or free-kick, the game continues.[66]

In the knockout stages of rugby competitions, most notably the Rugby World Cup, two extra time periods of 10 minutes periods are played (with an interval of 5 minutes in between) if the game is tied after full-time. If scores are level after 100 minutes then the rules call for 20 minutes of sudden-death extra time to be played. If the sudden-death extra time period results in no scoring a kicking competition is used to determine the winner. However, no match in the history of the Rugby World Cup has ever gone past 100 minutes into a sudden-death extra time period.[67]

Passing and kicking

pass the ball

Forward passing (throwing the ball ahead to another player) is not allowed; the ball can be passed laterally or backwards.[68] The ball tends to be moved forward in three ways—by kicking, by a player running with it or within a scrum or maul. Only the player with the ball may be tackled or rucked. A "knock-on" is committed when a player knocks the ball forward, and play is restarted with a scrum.[68]

Any player may kick the ball forward in an attempt to gain territory. When a player anywhere in the playing area kicks indirectly into touch so that the ball first bounces in the field of play, the throw-in is taken where the ball went into touch.[69] If the player kicks directly into touch (i.e. without bouncing in-field first) from within one's own 22-metre (24-yard) line, the lineout is taken by the opposition where the ball went into touch, but if the ball is kicked into touch directly by a player outside the 22-metre (24-yard) line, the lineout is taken level to where the kick was taken.[69]

Breakdowns

The aim of the defending side is to stop the player with the ball, either by bringing them to ground (a tackle, which is frequently followed by a ruck) or by contesting for possession with the ball-carrier on their feet (a maul). Such a circumstance is called a breakdown and each is governed by a specific law.

Tackling

A player may tackle an opposing player who has the ball by holding them while bringing them to ground. Tacklers cannot tackle above the shoulder (the neck and head are out of bounds),[70] and the tackler has to attempt to wrap their arms around the player being tackled to complete the tackle. It is illegal to push, shoulder-charge, or to trip a player using feet or legs, but hands may be used (this being referred to as a tap-tackle or ankle-tap).[71][72] Tacklers may not tackle an opponent who has jumped to catch a ball until the player has landed.[70]

Rucking and Mauling

Mauls occur after a player with the ball has come into contact with an opponent but the handler remains on his feet; once any combination of at least three players have bound themselves a maul has been set.[50] A ruck is similar to the maul, but in this case the ball has gone to ground with at least three attacking players binding themselves on the ground in an attempt to secure the ball.[50]

Set pieces

Lineout

When the ball leaves the side of the field, a line-out is awarded against the team which last touched the ball.[73] Forward players from each team line up a metre apart, perpendicular to the touchline and between 5 and 15 m (5.5 and 16.4 yd) from the touchline.[73] The ball is thrown from the touchline down the centre of the lines of forwards by a player (usually the hooker) from the team that did not play the ball into touch.[73] The exception to this is when the ball went out from a penalty, in which case the side who gained the penalty throws the ball in.[73]

Both sides compete for the ball and players may lift their teammates.[74] A jumping player cannot be tackled until they stand and only shoulder-to-shoulder contact is allowed; deliberate infringement of this law is dangerous play, and results in a penalty kick.[75]

Scrum

A scrum is a way of restarting the game safely and fairly after a minor infringement.[76] It is awarded when the ball has been knocked or passed forward, if a player takes the ball over their own try line and puts the ball down, when a player is accidentally offside or when the ball is trapped in a ruck or maul with no realistic chance of being retrieved. A team may also opt for a scrum if awarded a penalty.[76]

A scrum is formed by the eight forwards from each team crouching down and binding together in three rows, before interlocking with the opposing team.[76] For each team, the front row consists of two props (loosehead and tighthead) either side of the hooker.[76] The two props are typically amongst the strongest players on the team. The second row consists of two locks and the two flankers. Behind the second row is the number 8. This formation is known as the 3–4–1 formation.[77] Once a scrum is formed the scrum-half from the team awarded the feed rolls the ball into the gap between the two front-rows known as the tunnel.[76] The two hookers then compete for possession by hooking the ball backwards with their feet, while each pack tries to push the opposing pack backwards to help gain possession.[76] The side that wins possession can either keep the ball under their feet while driving the opposition back, in order to gain ground, or transfer the ball to the back of the scrum where it can be picked up by the number 8 or by the scrum-half.[76]

Officials and offences

There are three match officials: a referee, and two assistant referees. The referees are commonly addressed as "Sir".[78] The latter, formerly known as touch judges, had the primary function of indicating when the ball had gone into "touch"; their role has been expanded and they are now expected to assist the referee in a number of areas, such as watching for foul play and checking offside lines.[78] In addition, for matches in high level competitions, there is often a television match official (TMO; popularly called the "video referee"), to assist with certain decisions, linked up to the referee by radio.[79] The referees have a system of hand signals to indicate their decision. [80]

Common offences include tackling above the shoulders, collapsing a scrum, ruck or maul, not releasing the ball when on the ground, or being offside.[81] The non-offending team has a number of options when awarded a penalty: a "tap" kick, when the ball is kicked a very short distance from hand, allowing the kicker to regather the ball and run with it; a punt, when the ball is kicked a long distance from hand, for field position; a place-kick, when the kicker will attempt to score a goal; or a scrum.[81] Players may be sent off (signalled by a red card) or temporarily suspended ("sin-binned") for ten minutes (yellow card) for foul play or repeated infringements, and may not be replaced.[81]

Occasionally, infringements are not caught by the referee during the match and these may be "cited" by the citing commissioner after the match and have punishments (usually suspension for a number of weeks) imposed on the infringing player.[82]

Replacements and substitutions

During the match, players may be replaced (for injury) or substituted (for tactical reasons).[47] A player who has been replaced may not rejoin play unless he was temporarily replaced to have bleeding controlled; a player who has been substituted may return temporarily, to replace a player who has a blood injury or has suffered a concussion, or permanently, if he is replacing a front-row forward.[47] In international matches, eight replacements are allowed; in domestic or cross-border tournaments, at the discretion of the responsible national union(s), the number of replacements may be nominated to a maximum of eight, of whom three must be sufficiently trained and experienced to provide cover for the three front row positions.[47][83]

Prior to 2016, all substitutions, no matter the cause, counted against the limit during a match. In 2016, World Rugby changed the law so that substitutions made to replace a player deemed unable to continue due to foul play by the opposition would no longer count against the match limit. This change was introduced in January of that year in the Southern Hemisphere and June in the Northern Hemisphere.[84]

Equipment

The most basic items of equipment for a game of rugby union are the ball itself, a rugby shirt (also known as a "jersey"), rugby shorts, socks, and boots. The rugby ball is oval in shape (technically a prolate spheroid), and is made up of four panels.[85] The ball was historically made of leather, but in the modern era most games use a ball made from a synthetic material. World Rugby lays out specific dimensions for the ball, 280–300 mm (11–12 in) in length, 740–770 mm (29–30 in) in circumference of length and 580–620 mm (23–24 in) in circumference of width.[85] Rugby boots have soles with studs to allow grip on the turf of the pitch. The studs may be either metal or plastic but must not have any sharp edges or ridges.[86]

Protective equipment is optional and strictly regulated. The most common items are mouthguards, which are worn by almost all players, and are compulsory in some rugby-playing nations.[87] Other protective items that are permitted include headgear; thin (not more than 10 mm thick), non-rigid shoulder pads and shin guards; which are worn underneath socks.[86] Bandages or tape can be worn to support or protect injuries; some players wear tape around the head to protect the ears in scrums and rucks. Female players may also wear chest pads.[86] Although not worn for protection, some types of fingerless mitts are allowed to aid grip.[86]

It is the responsibility of the match officials to check players' clothing and equipment before a game to ensure that it conforms to the laws of the game.[86]

Governing bodies

The international governing body of rugby union (and associated games such as sevens) is World Rugby (WR).[88] The WR headquarters are in Dublin, Ireland.[88] WR, founded in 1886, governs the sport worldwide and publishes the game's laws and rankings.[88] As of February 2014, WR (then known as the IRB, for International Rugby Board) recorded 119 unions in its membership, 101 full members and 18 associate member countries.[3] According to WR, rugby union is played by men and women in over 100 countries.[88] WR controls the Rugby World Cup,[88] the Women's Rugby World Cup,[89] Rugby World Cup Sevens,[90] HSBC Sevens Series,[91] HSBC Women's Sevens Series,[92] World Under 20 Championship,[93] World Under 20 Trophy,[94] Nations Cup[95] and the Pacific Nations Cup.[96] WR holds votes to decide where each of these events are to be held, except in the case of the Sevens World Series for men and women, for which WR contracts with several national unions to hold individual events.

Six regional associations, which are members of WR, form the next level of administration; these are:

- Rugby Africa, formerly Confederation of African Rugby (CAR)[97]

- Asia Rugby, formerly Asian Rugby Football Union (ARFU)[98]

- Rugby Americas North, formerly North America Caribbean Rugby Association (NACRA)[99]

- Rugby Europe, previously Fédération Internationale de Rugby Amateur – Association Européenne de Rugby (FIRA-AER)[100]

- Oceania Rugby, formerly Federation of Oceania Rugby Unions (FORU)[101]

- Sudamérica Rugby, formerly Confederación Sudamericana de Rugby (South American Rugby Confederation, or CONSUR)[102]

SANZAAR (South Africa, New Zealand, Australia and Argentina Rugby) is a joint venture of the South African Rugby Union, New Zealand Rugby, Rugby Australia and the Argentine Rugby Union (UAR) that operates Super Rugby and The Rugby Championship (formerly the Tri Nations before the entry of Argentina).[103] Although UAR initially had no representation on the former SANZAR board, it was granted input into the organisation's issues, especially with regard to The Rugby Championship,[104] and became a full SANZAAR member in 2016 (when the country entered Super Rugby).

National unions oversee rugby union within individual countries and are affiliated to WR. Since 2016, the WR Council has 40 seats. A total of 11 unions—the eight foundation unions of England, Scotland, Ireland, Wales, Australia, New Zealand, South Africa and France, plus Argentina, Canada and Italy—have two seats each. In addition, the six regional associations have two seats each. Four more unions—Georgia, Japan, Romania and the USA—have one seat each. Finally, the chairman and Vice Chairman, who usually come from one of the eight foundation unions (although the current Vice Chairman, Agustín Pichot, is with the non-foundation Argentine union) have one vote each.[105][88]

Global reach

The earliest countries to adopt rugby union were England, the country of inception, and the other three Home Nations, Scotland, Ireland and Wales. The spread of rugby union as a global sport has its roots in the exporting of the game by British expatriates, military personnel, and overseas university students. The first rugby club in France was formed by British residents in Le Havre in 1872, while the next year Argentina recorded its first game: 'Banks' v 'City' in Buenos Aires.[106]

Seven countries have adopted rugby union as their de facto national sport; they are Fiji,[107] Georgia, Madagascar,[108][109][110] New Zealand,[111] Samoa,[112] Tonga[113] and Wales.[114]

Oceania

A rugby club was formed in Sydney, New South Wales, Australia in 1864; while the sport was said to have been introduced to New Zealand by Charles Monro in 1870, who played rugby while a student at Christ's College, Finchley.[14]

Several island nations have embraced the sport of rugby. Rugby was first played in Fiji circa 1884 by European and Fijian soldiers of the Native Constabulary at Ba on Viti Levu island.[115][116] Fiji then sent their first overseas team to Samoa in 1924, who in turn set up their own union in 1924.[117] Along with Tonga, other countries to have national rugby teams in Oceania include the Cook Islands, Niue, Papua New Guinea and Solomon Islands.[118]

North America and Caribbean

In North America a club formed in Montreal in 1868, Canada's first club. The city of Montreal also played its part in the introduction of the sport in the United States, when students of McGill University played against a team from Harvard University in 1874.[14][106] The two variants of gridiron football — Canadian football and, to a lesser extent, American football — were once considered forms of rugby football but are seldom now referred to as such. In fact, the governing body of Canadian football, Football Canada, was known as the Canadian Rugby Union (CRU) as late as 1967, more than fifty years after the sport parted ways with the established rules of rugby union. The Grey Cup, the trophy awarded to the victorious team playing in the namesake championship of the professional Canadian Football League (CFL), was originally awarded to the champion of the CRU. The two strongest leagues in the CRU, the Interprovincial Rugby Football Union in Eastern Canada and the Western Interprovincial Football Union in Western Canada, evolved into the present day CFL.

Although the exact date of arrival of rugby union in Trinidad and Tobago is unknown, their first club Northern RFC was formed in 1923, a national team was playing by 1927 and due to a cancelled tour to British Guiana in 1933, switched their venue to Barbados; introducing rugby to the island.[119][120] Other Atlantic countries to play rugby union include Jamaica[121] and Bermuda.[122]

Rugby union is the fastest growing college sport and sport in general in the US.[5][6][7]

Major League Rugby is the professional Rugby union competition in the US and Canada.

Europe

The growth of rugby union in Europe outside the 6 Nations countries in terms of playing numbers, attendances, and viewership has been sporadic. Historically, British and Irish home teams played the Southern Hemisphere teams of Australia, New Zealand, and South Africa, as well as France. The rest of Europe were left to play amongst themselves. During a period when it had been isolated by the British and Irish Unions, France, lacking international competition, became the only European team from the top tier to regularly play the other European countries; mainly Belgium, the Netherlands, Germany, Spain, Romania, Poland, Italy and Czechoslovakia.[100][123] In 1934, instigated by the French Rugby Federation, FIRA (Fédération Internationale de Rugby Amateur) was formed to organise rugby union outside the authority of the IRFB.[100] The founding members were Italy, Romania, Netherlands, Portugal, Czechoslovakia, and Sweden.

Other European rugby playing nations of note include Russia, whose first officially recorded match is marked by an encounter between Dynamo Moscow and the Moscow Institute of Physical Education in 1933.[124] Rugby union in Portugal also took hold between the First and Second World Wars, with a Portuguese National XV set up in 1922 and an official championship started in 1927.[125]

In 1999, FIRA agreed to place itself under the auspices of the IRB, transforming itself into a strictly European organising body. Accordingly, it changed its name to FIRA–AER (Fédération Internationale de Rugby Amateur – Association Européenne de Rugby). It adopted its current name of Rugby Europe in 2014.

South America

Although Argentina is the best-known rugby playing nation in South America, founding the Argentine Rugby Union in 1899,[126] several other countries on the continent have a long history. Rugby had been played in Brazil since the end of the 19th century, but the game was played regularly only from 1926, when São Paulo beat Santos in an inter-city match.[127] It took Uruguay several aborted attempts to adapt to rugby, led mainly by the efforts of the Montevideo Cricket Club; these efforts succeeded in 1951 with the formation of a national league and four clubs.[128] Other South American countries that formed a rugby union include Chile (1948),[129] and Paraguay (1968).[130]

Súper Liga Americana de Rugby is the professional Rugby union competition in South America.

Asia

Many Asian countries have a tradition of playing rugby dating from the British Empire. India began playing rugby in the early 1870s, the Calcutta Football Club forming in 1873. However, with the departure of a local British army regiment, interest in rugby diminished in the area.[131] In 1878, The Calcutta Football Club was disbanded, and rugby in India faltered.[132] Sri Lanka claims to have founded their union in 1878, and although little official information from the period is available, the team won the All-India cup in Madras in 1920.[133] The first recorded match in Malaysia was in 1892, but the first confirmation of rugby is the existence of the HMS Malaya Cup which was first presented in 1922 and is still awarded to the winners of the Malay sevens.[134]

Rugby union was introduced to Japan in 1899 by two Cambridge students: Ginnosuke Tanaka and Edward Bramwell Clarke.[135][136] The Japan RFU was founded in 1926 and its place in rugby history was cemented when Japan hosted the 2019 World Cup.[137] It was the first country outside the Commonwealth, Ireland and France to host the event, and was viewed by the IRB as an opportunity for rugby union to extend its reach,[137] particularly in Asia. Other Asian playing countries of note include Singapore, South Korea, China and The Philippines, while the former British colony of Hong Kong is notable within rugby for its development of the rugby sevens game, especially the Hong Kong Sevens tournament which was founded in 1976.[138]

Rugby in the Middle East and the Gulf States has its history in the 1950s, with clubs formed by British and French Services stationed in the region after the Second World War.[139] When these servicemen left, the clubs and teams were kept alive by young professionals, mostly Europeans, working in these countries. The official union of Oman was formed in 1971.[140] Bahrain founded its union a year later, while in 1975 the Dubai Sevens, the Gulf's leading rugby tournament, was created. Rugby remains a minority sport in the region with Israel and the United Arab Emirates, as of 2019, being the only member union from the Middle East to be included in the IRB World Rankings.[141]

Africa

In 1875, rugby was introduced to South Africa by British soldiers garrisoned in Cape Town.[106] The game spread quickly across the country, displacing Winchester College football as the sport of choice in South Africa and spreading to nearby Zimbabwe. South African settlers also brought the game with them to Namibia and competed against British administrators in British East Africa. During the late 19th and early 20th century, the sport in Africa was spread by settlers and colonials who often adopted a "whites-only" policy to playing the game. This resulted in rugby being viewed as a bourgeois sport by the indigenous people with limited appeal.[142] Despite this enclaves of black participation developed notably in the Eastern Cape and in Harare. The earliest countries to see the playing of competitive rugby include South Africa, and neighbouring Rhodesia (modern-day Zimbabwe), which formed the Rhodesia Rugby Football Union in 1895 and became a regular stop for touring British and New Zealand sides.[143]

In more recent times the sport has been embraced by several African nations. In the early 21st century Madagascar has experienced crowds of 40,000 at national matches,[144] while Namibia, whose history of rugby can be dated from 1915, have qualified for the final stages of the World Cup four times since 1999.[145] Other African nations to be represented in the World Rugby Rankings as Member Unions include Côte d'Ivoire, Kenya, Uganda and Zambia.[141] South Africa and Kenya are among the 15 "core teams" that participate in every event of the men's World Rugby Sevens Series.[146]

Women's rugby union

NC Hustlers vs. Midwest II

Records of women's rugby football date from the late 19th century, with the first documented source being Emily Valentine's writings, in which she states that she set up a rugby team in Portora Royal School in Enniskillen, Ireland in 1887.[147] Although there are reports of early women's matches in New Zealand and France, one of the first notable games to prove primary evidence was the 1917 war-time encounter between Cardiff Ladies and Newport Ladies; a photo of which shows the Cardiff team before the match at the Cardiff Arms Park.[148] Since the 1980s, the game has grown in popularity among female athletes, and by 2010, according to World Rugby, women's rugby was being played in over 100 countries.[149]

The English-based Women's Rugby Football Union (WRFU), responsible for women's rugby in England, Scotland, Ireland, and Wales, was founded in 1983, and is the oldest formally organised national governing body for women's rugby. This was replaced in 1994 by the Rugby Football Union for Women (RFUW) in England with each of the other Home Nations governing their own countries.[150]

The premier international competition in rugby union for women is the Women's Rugby World Cup, first held in 1991; from 1994 through 2014, it was held every four years.[150] After the 2014 event, the tournament was brought forward a year to 2017 to avoid clashing with other sporting cycles, in particular the Rugby World Cup Sevens competition.[151] The Women's Rugby World Cup returned to a four-year cycle after 2017, with future competitions to be held in the middle year of the men's World Cup cycle.

Major international competitions

Rugby World Cup

The most important competition in rugby union is the Rugby World Cup, a men's tournament that has taken place every four years since the inaugural event in 1987. South Africa are the reigning champions, having defeated England in the final of the 2019 Rugby World Cup in Yokohama. New Zealand and South Africa have each won the title three times (New Zealand: 1987, 2011, 2015; South Africa: 1995, 2007, 2019), Australia have won twice (1991 and 1999), and England once (2003). England is the only team from the Northern Hemisphere to have won the Rugby World Cup.[152]

The Rugby World Cup has continued to grow since its inception in 1987. The Rugby League World Cup dates from 1954 in contrast. The first tournament, in which 16 teams competed for the title, was broadcast to 17 countries with an accumulated total of 230 million television viewers. Ticket sales during the pool stages and finals of the same tournament was less than a million. The 2007 World Cup was contested by 94 countries with ticket sales of 3,850,000 over the pool and final stage. The accumulated television audience for the event, then broadcast to 200 countries, was a claimed 4.2 billion.[153]

The 2019 Rugby World Cup took place in Japan between 20 September and 2 November. It was the ninth edition and the first time the tournament has been held in Asia.[154]

Regional tournaments

Major international competitions are the Six Nations Championship and The Rugby Championship, held in Europe and the Southern Hemisphere respectively.[155]

The Six Nations is an annual competition involving the European teams England, France, Ireland, Italy, Scotland and Wales.[156] Each country plays the other five once. Following the first internationals between England and Scotland, Ireland and Wales began competing in the 1880s, forming the Home International Championships.[156] France joined the tournament in the 1900s and in 1910 the term Five Nations first appeared.[156] However, the Home Nations (England, Ireland, Scotland, and Wales) excluded France in 1931 amid a run of poor results, allegations of professionalism and concerns over on-field violence.[157] France then rejoined in 1939–1940, though World War II halted proceedings for a further eight years.[156] France has played in all the tournaments since WWII, the first of which was played in 1947.[156] In 2000, Italy became the sixth nation in the contest and Rome's Stadio Olimpico has replaced Stadio Flaminio as the venue for their home games since 2013.[158]

The Rugby Championship is the Southern Hemisphere's annual international series for that region's top national teams. From its inception in 1996 through 2011, it was known as the Tri Nations, as it featured the hemisphere's traditional powers of Australia, New Zealand and South Africa.[159] These teams have dominated world rankings in recent years, and many considered the Tri Nations to be the toughest competition in international rugby.[160][161] The Tri Nations was initially played on a home and away basis with the three nations playing each other twice.[162]

In 2006 a new system was introduced where each nation plays the others three times, though in 2007 and 2011 the teams played each other only twice, as both were World Cup years.[159] Since Argentina's strong performances in the 2007 World Cup,[163] after the 2009 Tri Nations tournament, SANZAR (South Africa, New Zealand and Australian Rugby) invited the Argentine Rugby Union (UAR) to join an expanded Four Nations tournament in 2012.[164] The competition has been officially rechristened as The Rugby Championship beginning with the 2012 edition. The competition reverted to the Tri Nations' original home-and-away format, but now involving four teams. In World Cup years, an abbreviated tournament is held in which each team plays the others only once. In 2020, the "Tri Nations" format was temporarily revived due to the withdrawal of South Africa owing to the COVID-19 pandemic.[165]

Rugby within multi-sport events

Rugby union was played at the Olympic Games in 1900, 1908, 1920 and 1924.[166] As per Olympic rules, the nations of Scotland, Wales and England were not allowed to play separately as they are not sovereign states. In 1900, France won the gold, beating Great Britain 27 points to 8 and defeating Germany 27 points to 17.[166] In 1908, Australia defeated Great Britain, claiming the gold medal, the score being 32 points to three.[166] In 1920, the United States, fielding a team with many players new to the sport of rugby, upset France in a shock win, eight points to zero. In 1924, the United States again defeated France 17 to 3, becoming the only team to win gold twice in the sport.[166]

In 2009 the International Olympic Committee voted with a majority of 81 to 8 that rugby union be reinstated as an Olympic sport in at least the 2016 and 2020 games, but in the sevens, 4-day tournament format.[37][167] This is something the rugby world has aspired to for a long time and Bernard Lapasset, president of the International Rugby Board, said the Olympic gold medal would be considered to be "the pinnacle of our sport" (Rugby Sevens).[168]

Rugby sevens has been played at the Commonwealth Games since the 1998 Games in Kuala Lumpur.[169] The most gold medal holders are New Zealand who have won the competition on four successive occasions until South Africa beat them in 2014.[170] Rugby union has also been an Asian Games event since the 1998 games in Bangkok, Thailand. In the 1998 and 2002 editions of the games, both the usual fifteen-a-side variety and rugby sevens were played, but from 2006 onwards, only rugby sevens was retained. In 2010, the women's rugby sevens event was introduced. The event is likely to remain a permanent fixture of the Asian Games due to elevation of rugby sevens as an Olympic sport from the 2016 Olympics onwards. The present gold medal holders in the sevens tournament, held in 2014, are Japan in the men's event and China in the women's.

Women's international rugby

Women's international rugby union began in 1982, with a match between France and the Netherlands played in Utrecht.[171] As of 2009 over six hundred women's internationals have been played by over forty different nations.[172]

The first Women's Rugby World Cup was held in Wales in 1991, and was won by the United States.[150] The second tournament took place in 1994, and from that time through 2014 was held every four years. The New Zealand Women's team then won four straight World Cups (1998, 2002, 2006, 2010)[173] before England won in 2014. Following the 2014 event, World Rugby moved the next edition of the event to 2017, with a new four-year cycle from that point forward.[174] New Zealand are the current World Cup holders.

As well as the Women's Rugby World Cup there are also other regular tournaments, including a Six Nations, run in parallel to the men's competition. The Women's Six Nations, first played in 1996 has been dominated by England, who have won the tournament on 14 occasions, including a run of seven consecutive wins from 2006 to 2012. However, since then, England have won only in 2017; reigning champion France have won in each even-numbered year (2014, 2016, 2018) whilst Ireland won in 2013 and 2015.

Professional rugby union

Rugby union has been professionalised since 1995. The following table shows professional and semi-professional rugby union competitions.

| Competition | Teams | Countries | Average Attendance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Super Rugby | 12[lower-alpha 1] | New Zealand (5), Australia (5), Fiji(1), Pacific Islands(1) | 20,384 |

| Premiership | 13 | England | 15,065 |

| Japan Rugby League One | 16 | Japan | 14,952 (2020)[175] |

| Top 14 | 14 | France | 14,055 (2019–2020) |

| Currie Cup | 9 | South Africa | 11,125 |

| United Rugby Championship | 16 | Ireland (4), Wales (4), Scotland (2), Italy (2), South Africa (4)[lower-alpha 2] | 8,586 |

| Mitre 10 Cup | 14 | New Zealand | 7,203 |

| Rugby Pro D2 | 16 | France | 4,222 |

| RFU Championship | 12 | England | 2,738 |

| Major League Rugby | 13 | Canada (1), United States (12) | 2,300[lower-alpha 3] |

| NRC | 8[lower-alpha 4] | Australia (7), Fiji (1) | 1,450 |

| Didi 10 | 10 | Georgia | Unknown |

| Rugby Premier League | 10 | Russia | Unknown |

| CEC Bank SuperLiga | 7 | Romania | Unknown |

| Global Rapid Rugby | 6 | Australia;(1), China (1), Fiji (1), Hong Kong (1), Malaysia (1), Samoa (1) | Unknown |

| Súper Liga Americana de Rugby | 6 | Argentina (1), Uruguay (1), Brazil (1), Chile (1), Paraguay (1), Colombia (1) | Unknown |

- Super Rugby peaked at 18 teams in 2016 and 2017, but reverted to 15 in 2018 with the loss of two teams from South Africa and one from Australia.

- The two South African teams that were dropped from Super Rugby after its 2017 season joined the renamed Pro14 for the 2017–18 season.

- (in 2018)

- The NRC began in 2014 with nine teams, all from Australia. It dropped to eight when one of Sydney's three original sides was removed after the 2015 season. The league returned to nine teams with the arrival of the Fijian Drua in 2017, but reverted to eight when a second Sydney side was removed after the 2017 season.

Variants

Rugby union has spawned several variants of the full-contact, 15-a-side game. The two most common differences in adapted versions are fewer players and reduced player contact.

The oldest variant is rugby sevens (sometimes 7s or VIIs), a fast-paced game which originated in Melrose, Scotland in 1883. In rugby sevens, there are only seven players per side, and each half is normally seven minutes. Major tournaments include the Hong Kong Sevens and Dubai Sevens, both held in areas not normally associated with the highest levels of the 15-a-side game.

A more recent variant of the sport is rugby tens (10s or Xs), a Malaysian invention with ten players per side.[176]

Touch rugby, in which "tackles" are made by simply touching the ball carrier with two hands, is popular both as a training game and more formally as a mixed sex version of the sport played by both children and adults.[177][178]

Several variants have been created to introduce the sport to children with a less physical contact.[179] Mini rugby is a version aimed at fostering the sport in children.[180][181] It is played with only eight players and on a smaller pitch.[180]

Tag Rugby is a version in which the players wear a belt with two tags attached by velcro, the removal of either counting as a 'tackle'. Tag Rugby also varies in that kicking the ball is not allowed.[182] Similar to Tag Rugby, American Flag Rugby, (AFR), is a mixed gender, non-contact imitation of rugby union designed for American children entering grades K-9.[183] Both American Flag Rugby and Mini Rugby differ from Tag Rugby in that they introduce more advanced elements of rugby union as the participants age.[180]

Other less formal variants include beach rugby and snow rugby.[179][184]

Influence on other sports

Rugby league was formed after the Northern Union broke from the Rugby Football Union in a disagreement over payment to players. It went on to change its laws and became a football code in its own right. The two sports continue to influence each other to this day.

American football[185][186] and Canadian football[187] are derived from early forms of rugby football.[187]

Australian rules football was influenced by rugby football and other games originating in English public schools.[188][189][190]

James Naismith took aspects of many sports including rugby to invent basketball.[191] The most obvious contribution is the jump ball's similarity to the line-out as well as the underhand shooting style that dominated the early years of the sport. Naismith played rugby at McGill University.[192]

Swedish football was a code whose rules were a mix of Association and Rugby football rules.[193][194]

Rugby lends its name to wheelchair rugby, a full-contact sport which contains elements of rugby such as crossing a try line with the ball to score.[195]

Statistics and records

According to a 2011 report by the Centre for the International Business of Sport, over four and a half million people play rugby union or one of its variants organised by the IRB.[196] This is an increase of 19 percent since the previous report in 2007.[197] The report also claimed that since 2007 participation has grown by 33 percent in Africa, 22 percent in South America and 18 percent in Asia and North America.[197] In 2014 the IRB published a breakdown of the total number of players worldwide by national unions. It recorded a total of 6.6 million players globally, of those, 2.36 million were registered members playing for a club affiliated to their country's union.[3] The 2016 World Rugby Year in Review reported 8.5 million players, of which 3.2 million were registered union players and 1.9 million were registered club players; 22% of all players were female.[198]

The most capped international player from the tier 1 nations is Welsh captain Alun Wyn Jones who has played over 150 internationals. While the top scoring tier 1 international player is New Zealand's Dan Carter, who has amassed 1442 points during his career.[199] In April 2010 Lithuania which is a second tier rugby nation, broke the record of consecutive international wins for second tier rugby nations. In 2016, the All Blacks of New Zealand set the new record 18 consecutive test wins among tier 1 rugby nations, bettering their previous consecutive run of 17.[200] This record was equalled by England on 11 March 2017 with a win over Scotland at Twickenham.[201] The highest scoring international match between two recognised unions was Hong Kong's 164–13 victory over Singapore on 27 October 1994.[202] While the largest winning margin of 152 points is held by two countries, Japan (a 155–3 win over Chinese Taipei) and Argentina (152–0 over Paraguay) both in 2002.[202]

The record attendance for a rugby union game was set on 15 July 2000 in which New Zealand defeated Australia 39–35 in a Bledisloe Cup game at Stadium Australia in Sydney before 109,874 fans.[203] The record attendance for a match in Europe of 104,000 (at the time a world record) was set on 1 March 1975 when Scotland defeated Wales 12–10 at Murrayfield in Edinburgh during the 1975 Five Nations Championship.[203] This crowd however is an estimate and contemporaneous newspaper accounts list a crowd of 80,000 only. The record attendance for a domestic club match is 99,124, set when Racing 92 defeated Toulon in the 2016 Top 14 final on 24 June at Camp Nou in Barcelona. The match had been moved from its normal site of Stade de France near Paris due to scheduling conflicts with France's hosting of UEFA Euro 2016.[204]

In culture

Thomas Hughes 1857 novel Tom Brown's Schooldays, set at Rugby School, includes a rugby football match, also portrayed in the 1940s film of the same name. James Joyce mentions Irish team Bective Rangers in several of his works, including Ulysses (1922) and Finnegans Wake (1939), while his 1916 semi-autobiographical work A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man has an account of Ireland international James Magee.[205] Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, in his 1924 Sherlock Holmes tale The Adventure of the Sussex Vampire, mentions that Dr Watson played rugby for Blackheath.[206]

Henri Rousseau's 1908 work Joueurs de football shows two pairs of rugby players competing.[207] Other French artists to have represented the sport in their works include Albert Gleizes' Les Joueurs de football (1912), Robert Delaunay's Football. L'Équipe de Cardiff (1916) and André Lhote's Partie de Rugby (1917).[208] The 1928 Gold Medal for Art at the Amsterdam Olympics was won by Luxembourg's Jean Jacoby for his work Rugby.[209]

In film, Ealing Studios' 1949 comedy A Run for Your Money and the 1979 BBC Wales television film Grand Slam both centre on fans attending a match.[210] Films that explore the sport in more detail include independent production Old Scores (1991) and Forever Strong (2008). Invictus (2009), based on John Carlin's book Playing the Enemy, explores the events of the 1995 Rugby World Cup and Nelson Mandela's attempt to use the sport to connect South Africa's people post-apartheid.[211][212]

In public art and sculpture there are many works dedicated to the sport. There is a 27 feet (8.2 m) bronze statue of a rugby line-out by pop artist Gerald Laing at Twickenham[213] and one of rugby administrator Sir Tasker Watkins at the Millennium Stadium.[214] Rugby players to have been honoured with statues include Gareth Edwards in Cardiff and Danie Craven in Stellenbosch.[215]

See also

- Experimental law variations

- International Rugby Hall of Fame, now merged with the former IRB Hall of Fame

- International rugby union eligibility rules

- International rugby union player records

- International rugby union team records

- List of international rugby union teams

- List of oldest rugby union competitions

- List of rugby union terms

- World Rugby Hall of Fame, a merger of the IRB and International Rugby Halls of Fame

- Concussions in rugby union

- List of rugby union stadiums by capacity

References

Notes

- As of 2014 the International Rugby Board, now known as World Rugby, removed the total breakdown of world-wide player numbers by country, by age and sex to publish instead an overall figure per country. This document, titled '119 countries... 6.6 million players' adds the number of registered and unregistered players reported by each country. Some unions only report their registered players, i.e. those who play for an affiliated club or region. Other unions, such as England's Rugby Football Union, also report people taking part in outreach and educational programs, or unregistered players. In the 2012 figures reported by the RFU they reported 1,990,988 people playing rugby in England, including 1,102,971 under 13s, 731,685 teens and 156,332 seniors. Some of those recorded would have experienced rugby via educational visits to schools, playing tag or touch rugby, rather than playing regularly for a club. The figures released in 2014 give an overall figure of those playing A7AAAAAAAAA rugby union, or one of its variants, as 6,684,118, but also reports that of that total, 3.36 million are registered players, while 4.3 million are unregistered.

- Although the United States national anthem, "The Star-Spangled Banner", was first sung before baseball games in the mid-19th century, it did not become the official national anthem until 1931. In addition, the song's pregame use did not become customary until the 1920s.[30]

Footnotes

- "The Origins of Rugby". hanazono-rugby-hos.com. Retrieved 26 December 2021.

- Else, David (2007). British language & culture (2nd ed.). Lonely Planet. p. 97. ISBN 978-1-86450-286-2.

- "119 countries... 6.6 million players" (PDF). IRB. Retrieved 27 February 2014.

- Scianitti, Matthew (18 June 2011). "The world awaits for Canada's rugby team". National Post. Archived from the original on 29 January 2013. Retrieved 8 March 2020.

- "U.S Rugby Scholarships – U.S Sports Scholarships".

- "Rugby: Fastest growing sport in the U.S. also one of the oldest – Global Sport Matters, Rugby: Fastest growing sport in the U.S. also one of the oldest – Global Sport Matters". 19 July 2018.

- "Where Is Rugby the Most Popular Among Students: Comparison of US and UK Student Leagues | Love Rugby League". 17 October 2020. Archived from the original on 12 August 2021. Retrieved 9 December 2020.

- "Madagascar take Sevens honours". International Rugby Board. 23 August 2007. Archived from the original on 24 October 2012. Retrieved 1 December 2013.

- Marshall & Jordon 1951, p. 13

- Marshall & Jordon 1951, pp. 13–14

- Godwin & Rhys 1981, p. 9

- "Six ways the town of Rugby helped change the world". BBC News. 1 February 2014. Archived from the original on 4 March 2014.

- "Early Laws". Rugbyfootballhistory.com. Retrieved 6 February 2010.

- Godwin & Rhys 1981, p. 10

- "History of Football – The Global Growth". FIFA. Archived from the original on 12 May 2013. Retrieved 12 November 2019.

- Tony Collins (2006). "Schism 1893–1895". Rugby's great split: class, culture and the origins of rugby league football (2nd ed.). Routlage. pp. 87–120. ISBN 0-415-39616-6.

- McGaughey, William. "A Short History of Civilization IV". Five Epochs of Civilization: Chapter 7 (2000). worldhistorysite.com. Archived from the original on 12 May 2013. Retrieved 26 September 2011.

- "Historical Rugby Milestones 1870s". Rugby Football History. Retrieved 22 March 2015.

- Godwin & Rhys 1981, p. 12

- "1888 Australia & New Zealand". The British and irish Lions. Archived from the original on 7 June 2011. Retrieved 13 August 2011.

- Ryan, Greg (1993). Forerunners of the All Blacks. Christchurch, New Zealand: Canterbury University Press. p. 44. ISBN 0-908812-30-2.

- "The History". lionsrugby.com. Retrieved 24 September 2011.

- "IRB Hall of Fame Welcomes Five Inductees". International Rugby Board. 23 November 2008. Archived from the original on 24 August 2010. Retrieved 24 September 2011.

- Griffiths 1987, p. ix "In the first century of rugby union's history the IRB only recognised matches with international status if both teams in a match came from a small pool of countries: Australia, British Lions, England, France, Ireland, New Zealand, Scotland, South Africa and Wales."

- "New Zealand Natives' rugby tour of 1888–9". New Zealand History Online. Retrieved 24 September 2011.

- "Take a trip down memory lane courtesy of our historian John Griffiths". espnscrum.com. 23 November 2008. Retrieved 6 October 2011. "1 October: The original Wallabies beat a strong Gloucestershire XV 16–0 at Kingsholm, 2 October: The Invincible Second All Blacks have their toughest tour assignment when they are considered lucky to scrape home 13–10 against a star-studded Newport XV, 2 October: Argentina serve notice of their rapidly rising rugby stock by beating a Cardiff side captained by Gerald Davies."

- Godwin & Rhys 1981, p. 18

- Thomas & Rowe 1954, p. 27 "When they arrived in this country [Britain] they were regarded as an unknown quantity, but it was not anticipated that they would give the stronger British teams a great deal of opposition. The result of the very first match against Devon was regarded as a foregone conclusion by most British followers."

- "The anthem in more recent years". BBC Cymru Wales history. BBC Cymru Wales. 1 December 2008. Retrieved 3 December 2010.

- Cyphers, Luke; Trex, Ethan (8 September 2011). "The song remains the same". ESPN The Magazine. Retrieved 20 November 2014.

- Godwin & Rhys 1981, p. 19

- "ITALY TOUR – Bucharest, 14 April 1940: Romania 3–0 Italy (FT)". ESPNscrum. Retrieved 12 November 2019.

- "ITALY TOUR – Stuttgart, 5 May 1940: Germany (0) 0–4 (4) Italy (FT)". ESPNscrum. Retrieved 12 November 2019.

- "ROMANIA TOUR – Milan, 2 May 1942: Italy (8) 22–3 (0) Romania (FT)". ESPNscrum. Retrieved 12 November 2019.

- Godwin & Rhys 1981, p. 22

- "Rugby in the Olympics: Future". IRB. Archived from the original on 10 August 2011. Retrieved 18 August 2011.

- Klein, Jeff (13 August 2009). "I.O.C. Decision Draws Cheers and Complaints From Athletes". The New York Times. Retrieved 13 August 2009.

- "Tokyo 2020 Olympic Sports: Rugby". Retrieved 25 June 2019.

- Stubbs 2009, p. 118

- "History of the RFU". RFU. Archived from the original on 22 April 2010. Retrieved 28 September 2011.

- "Ontario: The Shamateurs". TIME. 29 September 1947. Archived from the original on 3 February 2011. Retrieved 6 February 2010.

- Rentoul, John (17 March 1995). "Amateur status attacked by MPs — Sport — The Independent". The Independent. London: INM. ISSN 0951-9467. OCLC 185201487. Archived from the original on 25 December 2012. Retrieved 19 November 2011.

- "History of Rugby Union". Archived from the original on 6 April 2013. Retrieved 6 February 2010.

- "European Rugby Cup: History". ERC. Archived from the original on 8 February 2007. Retrieved 21 March 2007.

- Gaynor, Bryan (21 April 2001). "Union's off-field game a real winner". The New Zealand Herald.

- ""The Rugby Championship" to replace Tri Nations". rugby.com.au. Archived from the original on 8 March 2016. Retrieved 29 April 2014.

- "Law 3 Number of Players" (PDF). World Rugby. p. 33. Archived from the original (PDF) on 16 February 2015. Retrieved 28 September 2015.

- "A Beginner's Guide to Rugby Union" (PDF). World Rugby. p. 6. Retrieved 28 September 2015.

- "Rugby Union Positions". talkrugbyunion.co.uk. Archived from the original on 6 April 2013. Retrieved 13 August 2011.

- "Rugby Glossary". ESPN Scrum.com. Retrieved 13 August 2011.

- "Rugby Positions Explained". Rugby Coaching. 27 September 2011. Archived from the original on 3 April 2013. Retrieved 30 September 2012.

- "A Beginner's Guide to Rugby Union" (PDF). World Rugby. p. 7. Retrieved 28 September 2015.

- "A Beginner's Guide to Rugby Union" (PDF). World Rugby. p. 8. Retrieved 28 September 2015.

- Bompa & Claro 2008, p. 62

- Brown, Guthrie and Growden & (2010)

- Ferguson, David (7 January 2006). "Scottish rugby welcomes back Lomu". The Scotsman. Retrieved 1 September 2011.

- MacDonald, H. F. (1938). Rugger Practice and Tactics – A Manual of Rugby Football Technique. p. 97.

- "Law 9 Method of Scoring" (PDF). World Rugby. pp. 62–65. Archived from the original (PDF) on 16 February 2015. Retrieved 28 September 2015.

- "Scoring through the ages". rugbyfootballhistory.com. Retrieved 16 August 2011.

- worldrugby.org. "Laws of the Game | World Rugby Laws". www.world.rugby. Retrieved 18 August 2021.

- "The Field of play | IFAB". www.theifab.com. Retrieved 18 August 2021.

- "Bledisloe Cup 2018: 'Annoying' on-field advertising causes major distraction for television viewers". www.sportingnews.com. Retrieved 18 August 2021.

- "A Guide to Rugby Pitch Dimensions, Sizes and Markings: Everything you ever needed to know". Retrieved 25 June 2019.

- "Law 13 Kick-off and Restart Kicks" (PDF). World Rugby. pp. 85–91. Archived from the original (PDF) on 16 February 2015. Retrieved 28 September 2015.

- Midgley, Ruth (1979). The Official World Encyclopedia of Sports and Games. London: Diagram Group. p. 394. ISBN 0-7092-0153-2.

- "Law 5: Time" (PDF). World Rugby. pp. 45–47. Archived from the original (PDF) on 16 February 2015. Retrieved 27 February 2014.

- "IRB Laws – Time". 7 December 2013. Archived from the original on 25 March 2008. Retrieved 7 December 2013.

- "Law 12 Knock-on or Throw Forward" (PDF). World Rugby. pp. 81–83. Archived from the original (PDF) on 16 February 2015. Retrieved 28 September 2015.

- "Law 19 Touch and Lineout" (PDF). World Rugby. pp. 117–137. Archived from the original (PDF) on 16 February 2015. Retrieved 28 September 2015.

- "Law 10 Foul play". IRB. p. 10.4(e). Archived from the original on 22 October 2014. Retrieved 26 April 2016.

- "Law 10 Foul play". IRB. p. 10.4(d). Archived from the original on 9 February 2014. Retrieved 27 February 2014.