Russification

Russification (Russian: русификация, romanized: rusifikatsiya), or Russianization, is a form of cultural assimilation in which non-Russians, whether involuntarily or voluntarily, give up their culture and language in favor of the Russian culture and the Russian language.

In a historical sense, the term refers to both official and unofficial policies of the Russian Empire and the Soviet Union with respect to their national constituents and to national minorities in Russia, aimed at Russian domination and hegemony.

The major areas of Russification are politics and culture. In politics, an element of Russification is assigning Russian nationals to leading administrative positions in national institutions. In culture, Russification primarily amounts to the domination of the Russian language in official business and the strong influence of the Russian language on national idioms. The shifts in demographics in favour of the ethnic Russian population are sometimes considered as a form of Russification as well.

Analytically, it is helpful to distinguish Russification, as a process of changing one's ethnic self-label or identity from a non-Russian ethnonym to Russian, from Russianization, the spread of the Russian language, culture, and people into non-Russian cultures and regions, distinct also from Sovietization or the imposition of institutional forms established by the Communist Party of the Soviet Union throughout the territory ruled by that party.[1] In this sense, although Russification is usually conflated across Russification, Russianization, and Russian-led Sovietization, each can be considered a distinct process. Russianization and Sovietization, for example, did not automatically lead to Russification – change in language or self-identity of non-Russian peoples to being Russian. Thus, despite long exposure to the Russian language and culture, as well as to Sovietization, at the end of the Soviet era non-Russians were on the verge of becoming a majority of the population in the Soviet Union.[2]

History

An early case of Russification took place in the 16th century in the conquered Khanate of Kazan (medieval Tatar state which occupied the territory of former Volga Bulgaria) and other Tatar areas. The main elements of this process were Christianization and implementation of the Russian language as the sole administrative language.

After the Russian defeat in the Crimean War in 1856 and the Polish rebellion of 1863, Tsar Alexander II increased Russification to reduce the threat of future rebellions. Russia was populated by many minority groups, and forcing them to accept the Russian culture was an attempt to prevent self-determination tendencies and separatism. In the 19th century, Russian settlers on traditional Kazakh land (misidentified as Kyrgyz at the time) drove many of the Kazakhs over the border to China.[3]

Azerbaijan

Russian was introduced to the South Caucasus following its colonisation in the first half of the nineteenth century after Qajar Iran was forced to cede its Caucasian territories per the Treaty of Gulistan and Treaty of Turkmenchay in 1813 and 1828 respectively to Russia.[4] By 1830 there were schools with Russian as the language of instruction in the cities of Shusha, Baku, Yelisavetpol (Ganja), and Shemakha (Shamakhi); later such schools were established in Kuba (Quba), Ordubad, and Zakataly (Zaqatala). Education in Russian was unpopular amongst ethnic Azerbaijanis until 1887 when Habib bey Mahmudbeyov and Sultan Majid Ganizadeh founded the first Russian–Azerbaijani school in Baku. A secular school with instruction in both Russian and Azeri, its programs were designed to be consistent with cultural values and traditions of the Muslim population.[5] Eventually 240 such schools for both boys and girls, including a women's college founded in 1901, were established prior to the "Sovietization" of the South Caucasus.[6] The first Russian-Azeri reference library opened in 1894.[7] In 1918, during the short period of the Azerbaijan's independence, the government declared Azeri the official language, but the use of Russian in government documents was permitted until all civil servants mastered the official language.[8]

In the Soviet era, the large Russian population of Baku, the quality and prospects of education in Russian, increased access to Russian literature, and other factors contributed to the intensive Russification of the Baku's population. Its direct result by the mid-twentieth century was the formation of a supra-ethnic urban Baku subculture, uniting people of Russian, Azerbaijani, Armenian, Jewish, and other origins and whose special features were being cosmopolitan and Russian-speaking.[9][10][11] The widespread use of Russian resulted in a phenomenon of 'Russian-speaking Azeris', i.e. an emergence of an urban community of Azerbaijani-born ethnic Azeris who considered Russian their native language.[12] In 1970, 57,500 Azeris (1.3%) identified Russian as their native language.[13]

Belarus

Russian and Soviet authorities conducted policies of Russification of Belarus from 1772 to 1991, interrupted by the Belarusization policy in the 1920s.

With the gaining to the power of pro-Russian president Alexander Lukashenko in 1994, the Russification policy was renewed.[14][15][16][17]

Finland

The Russification of Finland (1899–1905, 1908–1917), sortokaudet ("times of oppression" in Finnish) was a governmental policy of the Russian Empire aimed at the termination of Finland's autonomy. Finnish opposition to Russification was one of the main factors that ultimately led to Finland's declaration of independence in 1917.

Latvia

On September 14, 1885, an ukaz was signed by Alexander III setting the mandatory use of Russian for Baltic governorate officials. In 1889, it was extended to apply to official proceedings of the Baltic municipal governments as well.[18] By the beginning of 1890s, Russian was enforced as the language of instruction in Baltic governorate schools.[19]

After Soviet re-occupation of Latvia in 1944, Russian became the language of State business, and Russian served as the language of inter-ethnic communication among the increasingly urbanized non-Russian ethnic groups, making cities major centres for the use of Russian language and made functional bilingualism in Russian a minimum necessity for the local population.[20]

In an attempt to partially reverse the Soviet Russification policies and give the Latvian language more equal positions to Russian, the so-called Latvian national communist faction within the Communist Party of Latvia passed a bill in 1957 that made the knowledge of both Latvian and Russian obligatory for all Communist Party employees, government functionaries and service sector staff. The law included a 2-year deadline for gaining proficiency in both languages.[21]

In 1958, as the two-year deadline for the bill was approaching, the Communist Party of the Soviet Union set out to enact an education reform, a component of which, the so-called Thesis 19, would give parents in all of the Soviet Republics, with the exception of Russian SSR, a choice for their children in public schools to study either the language of the republic's titular nation (in this case Latvian) or Russian, as well as one foreign language, in contrast, to the previous education system, where it was mandatory for school children to learn all three languages.[21]

Due to strong opposition from the Latvian national communists and the Latvian public, Latvian SSR was only one of two of the 12 Soviet Republics that did not yield to the increasing pressure to adopt Thesis 19 and excluded its contents from their ratified statutes. This led to the eventual purge of the Latvian national communists from the Communist Party ranks between 1959 and 1962. A month after the removal of the Latvian National Communist leader Eduards Berklavs All-Union legislation was implemented in Latvia by Arvīds Pelše.[21]

In an attempt to further widen the use of Russian and reverse the work of the national communists, a bilingual school system was established in Latvia, with parallel classes being taught in both Russian and Latvian. The number of such schools increased dramatically, including regions where the Russian population was minimal, and by July 1963 there were already 240 bilingual schools.[21]

The effect of the reform was the gradual decline in the number of assigned hours for learning Latvian in Russian schools and the increase of hours allocated for learning Russian in Latvian schools. In 1964–1965 the total weekly average of Latvian language classes and Russian language and literature classes in Latvian schools across all grades was reported to be 38.5 and 72.5 hours respectively, in comparison with 79 hours being devoted to Russian language and 26 hours being devoted to Latvian language and literature in Russian schools. The reform has been attributed to the persistence of poor Latvian language knowledge among Russians living in Latvia and the increasing language gap between Latvians and Russians.[21]

In 1972, the Letter of 17 Latvian communists, was smuggled outside the Latvian SSR and circulated in the Western world, accusing Communist Party of the Soviet Union of "Great Russian chauvinism" and "progressive Russification of all life in Latvia":[22]

The first main task is to transfer from Russia, Belorussia, and the Ukraine as many Russians, Belorussians and Ukrainians as possible, and to resettle them permanently in Latvia (...) Now the republic already has a number of large enterprises where there are almost no Latvians among the workers, engineering-technical personnel, and directors (...); there are also those where most of the workers are Latvians, but none of the executives understands Latvian (...) About 65% of the doctors working in municipal health institutions do not speak Latvian (...) Demands of the newcomers to increase Russian-language radio and television broadcasts in the republic are being satisfied. At the present time one radio program and one television program is broadcast entirely in Russian, and the other program is mixed. Thus about two-thirds of the radio and television broadcasts in the republic are in Russian. (...) about half of the periodicals published in Latvia are in Russian anyway. Works of Latvian writers and school textbooks in Latvian cannot be published, because there is a lack of paper, but books written by Russian authors and school textbooks in Russian are published. (..) There are many collectives where Latvians have an absolute majority. Nevertheless, if there is a single Russian in the collective, he will demand that the meeting be conducted in Russian, and his demand will be satisfied. If this is not done, then the collective is accused of nationalism.[23]

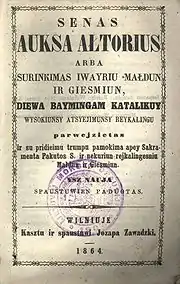

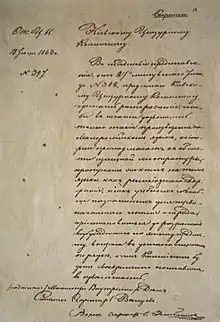

Lithuania and Poland

In 19th century, the Russian Empire strove to replace the Ukrainian, Polish, Lithuanian, and Belarusian languages and dialects by Russian in those areas, which were annexed by the Russian Empire after the Partitions of Poland (1772–1795) and the Congress of Vienna (1815). Imperial Russia faced a crucial critical cultural situation by 1815:

Large sections of Russian society had come under foreign influence as a result of the Napoleonic wars and appeared open to change. As a consequence of absorbing so much Polish territory, by 1815 no less than 64 per cent of the nobility of the Romanov realm was of Polish descent, and since there were more literate Poles than Russians, more people within it could read and write Polish than Russian. The third largest city, Vilnius, was entirely Polish in character and its university was the best in the Empire.[24]

Russification in Congress Poland intensified after the November Uprising of 1831, and in particular after the January Uprising of 1863.[25] In 1864, the Polish and Belarusian languages were banned in public places; in the 1880s, Polish was banned in schools, on school grounds and in the offices of Congress Poland. Research and teaching of the Polish language, of Polish history or of Catholicism were forbidden. Illiteracy rose as Poles refused to learn Russian. Students were beaten for resisting Russification.[26] A Polish underground education network formed, including the famous Flying University. According to Russian estimates, by 1901 one-third of the inhabitants in the Congress Poland was involved in clandestine education based on Polish literature.[27]

Starting in the 1840s, Russia considered introducing Cyrillic script for spelling the Polish language, with the first school books printed in the 1860s; the reform was eventually deemed unnecessary because of introduction of school education in the Russian language.[28]

A similar development took place in Lithuania.[25] Its Governor General, Mikhail Muravyov (in office 1863–1865), prohibited the public use of spoken Polish and Lithuanian and closed Polish and Lithuanian schools; teachers from other parts of Russia who did not speak these languages were moved in to teach pupils. Muravyov also banned the use of Latin and Gothic scripts in publishing. He was reported as saying, "What the Russian bayonet didn't accomplish, the Russian school will." ("Что не додѣлалъ русскій штыкъ – додѣлаетъ русская школа.") This ban, lifted only in 1904, was disregarded by the Knygnešiai, the Lithuanian book smugglers, who brought Lithuanian publications printed in the Latin alphabet, the historic orthography of the Lithuanian language, from Lithuania Minor (part of East Prussia) and from the United States into the Lithuanian-speaking areas of Imperial Russia. The knygnešiai came to symbolise the resistance of Lithuanians against Russification.

The Russification campaign also promoted the Russian Orthodox faith over Catholicism. The measures used included closing down Catholic monasteries, officially banning the building of new churches and giving many of the old ones to the Russian Orthodox church, banning Catholic schools and establishing state schools which taught only the Orthodox religion, requiring Catholic priests to preach only officially approved sermons, requiring that Catholics who married members of the Orthodox church convert, requiring Catholic nobles to pay an additional tax in the amount of 10% of their profits, limiting the amount of land a Catholic peasant could own, and switching from the Gregorian calendar (used by Catholics) to the Julian one (used by members of the Orthodox church).

Most of the Orthodox Church property in the 19th century Congress Poland was acquired at the expense of the Catholic Church of both rites (Roman and Greek Catholic).[29]

After the 1863 January Uprising, many manors and great chunks of land were confiscated from nobles of Polish and Lithuanian descent who were accused of helping the uprising; these properties were later given or sold to Russian nobles. Villages where supporters of the uprising lived were repopulated by ethnic Russians. Vilnius University, where the language of instruction had been Polish rather than Russian, closed in 1832. Lithuanians and Poles were banned from holding any public jobs (including professional positions, such as teachers and doctors) in Lithuania; this forced educated Lithuanians to move to other parts of the Russian Empire. The old legal code was dismantled and a new one based on the Russian code and written in the Russian language was enacted; Russian became the only administrative and juridical language in the area. Most of these actions ended at the beginning of the Russo-Japanese War of 1904–1905, but others took longer to be reversed; Vilnius University re-opened only after Russia had lost control of the city in 1919.

Bessarabia/Moldova

Bessarabia was annexed by the Russian Empire in 1812. In 1816 Bessarabia became an autonomous state, but only until 1828. In 1829, the use of the Romanian language was forbidden in the administration. In 1833, the use of the Romanian language was forbidden in churches. In 1842, teaching in Romanian was forbidden in secondary schools; it was forbidden in elementary schools in 1860.

The Russian authorities encouraged the migration of Moldovans to other provinces of the Russian Empire (especially in Kuban, Kazakhstan and Siberia), while foreign ethnic groups (especially Russians and Ukrainians, called in the 19th century "Little Russians") were encouraged to settle there. Though the 1817 census did not record ethnicity, Romanian authors have claimed that Bessarabia was populated at the time by 86% Moldovans, 6.5% Ukrainians, 1.5% Russians (Lipovans) and 6% other ethnic groups. 80 years later, in 1897, the ethnic structure was very different: only 56% Moldovans, but 11.7% Ukrainians, 18.9% Russians and 13.4% other ethnic groups.[30] During 80 years, between 1817 and 1897, the share of the Moldovan population dropped by 30%.

After the Soviet occupation of Bessarabia in 1940, the Romanian population of Bessarabia was persecuted by Soviet authorities, especially in the years following the annexation, based mostly on social, educational, and political grounds; because of this, Russification laws were imposed again on the Romanian population. The Moldovan language promoted during the Interwar period by the Soviet authorities first in the Moldavian Autonomous Soviet Socialist Republic, and after 1940 taught in the Moldavian Soviet Socialist Republic, was actually the Romanian language but written with a version of the Cyrillic script derived from the Russian alphabet. Proponents of Cyrillic orthography argue that the Romanian language was historically written with the Cyrillic script, albeit a different version of it (see Moldovan alphabet and Romanian Cyrillic alphabet for a discussion of this controversy).[31]

The cultural and linguistic effects of Russification manifest themselves in persistent identity questions. During the breakup of the Soviet Union, this led to the separation of a large and industrialized portion of the country, becoming the de facto independent state of Transnistria, whose main official language is Russian.

Ukraine

Russian and Soviet authorities conducted policies of Russification of Ukraine from 1709 to 1991, interrupted by the Korenizatsiya policy in the 1920s. Since Ukraine's independence, its government has implemented Ukrainization policies to decrease the use of Russian and favour Ukrainian.

A number of Ukrainian activists died by suicide in protest against Russification, including Vasyl Makukh in 1968 and Oleksa Hirnyk in 1978.

After the 2014 Russian Annexation of Crimea and establishment of unrecognized Russian-supported militants in eastern Ukraine, Russification was imposed on people in these areas.[32]

Uralic-speaking peoples

Indigenous to large parts of western and central Russia are speakers of the Uralic languages, such as the Vepsians, Mordvins, Maris and Permians. Historically, the Russification of these peoples begins already with the original eastward expansion of the East Slavs. Written records of the oldest period are scarce, but toponymic evidence indicates[33][34][35] that this expansion was accomplished at the expense of various Volga-Finnic peoples, who were gradually assimilated by Russians; beginning with the Merya and the Muroma in the early 2nd millennium AD.

The Russification of the Komi began in the 13th to 14th centuries but did not penetrate into the Komi heartlands until the 18th century. Komi-Russian bilingualism has become the norm over the 19th and has led to increasing Russian influence in the Komi language.[36]

The enforced Russification of Russia's remaining indigenous minorities has intensified particularly during the Soviet era and continues unabated in the 21st century, especially in connection to urbanization and the dropping population replacement rates (particularly low among the more western groups). As a result, several of Russia's indigenous languages and cultures are currently considered endangered. E.g. between the 1989 and 2002 censuses, the assimilation numbers of the Mordvins have totalled over 100,000, a major loss for a people totalling less than one million in number.[37]

Under the Soviet Union

After the 1917 revolution, authorities in the USSR decided to abolish the use of the Arabic alphabet in native languages in Soviet-controlled Central Asia, in the Caucasus, and in the Volga region (including Tatarstan). This detached the local Muslim populations from exposure to the language and writing system of the Quran. The new alphabet for these languages was based on the Latin alphabet and was also inspired by the Turkish alphabet. However, by the late 1930s, the policy had changed. In 1939–1940 the Soviets decided that a number of these languages (including Tatar, Kazakh, Uzbek, Turkmen, Tajik, Kyrgyz, Azerbaijani, and Bashkir) would henceforth use variations of the Cyrillic script. It was claimed that the switch was made "by the demands of the working class."

Early 1920s through mid-1930s: Indigenization

Stalin's Marxism and the National Question (1913) provided the basic framework for nationality policy in the Soviet Union.[38] The early years of said policy, from the early 1920s to the mid-1930s, were guided by the policy of korenizatsiya ("indigenization"), during which the new Soviet regime sought to reverse the long-term effects of Russification on the non-Russian populations.[39] As the regime was trying to establish its power and legitimacy throughout the former Russian empire, it went about constructing regional administrative units, recruiting non-Russians into leadership positions, and promoting non-Russian languages in government administration, the courts, the schools, and the mass media. The slogan then established was that local cultures should be "socialist in content but national in form." That is, these cultures should be transformed to conform with the Communist Party's socialist project for the Soviet society as a whole but have active participation and leadership by the indigenous nationalities and operate primarily in the local languages.

Early nationalities policy shared with later policy the object of assuring control by the Communist Party over all aspects of Soviet political, economic, and social life. The early Soviet policy of promoting what one scholar has described as "ethnic particularism"[40] and another as "institutionalized multinationality",[41] had a double goal. On the one hand, it had been an effort to counter Russian chauvinism by assuring a place for non-Russian languages and cultures in the newly formed Soviet Union. On the other hand, it was a means to prevent the formation of alternative ethnically based political movements, including pan-Islamism[42] and pan-Turkism.[43] One way of accomplishing this was to promote what some regard as artificial distinctions between ethnic groups and languages rather than promoting amalgamation of these groups and a common set of languages based on Turkish or another regional language.[44]

The Soviet nationalities policy from its early years sought to counter these two tendencies by assuring a modicum of cultural autonomy to non-Russian nationalities within a federal system or structure of government, though maintaining that the ruling Communist Party was monolithic, not federal. A process of "national-territorial delimitation" (ru:национально-территориальное размежевание) was undertaken to define the official territories of the non-Russian populations within the Soviet Union. The federal system conferred highest status to the titular nationalities of union republics, and lower status to the titular nationalities of autonomous republics, autonomous provinces, and autonomous okrugs. In all, some 50 nationalities had a republic, province, or okrug of which they held nominal control in the federal system. Federalism and the provision of native-language education ultimately left as a legacy a large non-Russian public that was educated in the languages of their ethnic groups and that identified a particular homeland on the territory of the Soviet Union.

Late 1930s and wartime: Russian comes to the fore

By the late 1930s, however, there was a notable policy shift. Purges in some of the national regions, such as Ukraine, had occurred already in the early 1930s. Before the turnabout in Ukraine in 1933, a purge of Veli Ibrahimov and his leadership in the Crimean ASSR in 1929 for "national deviation" led to the Russianization of government, education, and the media and to the creation of a special alphabet for Crimean Tatar to replace the Latin alphabet.[45] Of the two dangers that Joseph Stalin had identified in 1923, now bourgeois nationalism (local nationalism) was said to be a greater threat than Great Russian chauvinism (great power chauvinism). In 1937, Faizullah Khojaev and Akmal Ikramov were removed as leaders of the Uzbek SSR and in 1938, during the third great Moscow show trial, convicted and subsequently put to death for alleged anti-Soviet nationalist activities.

After Stalin, a Russified Georgian, became the undisputed leader of the Soviet Union, the Russian language gained greater emphasis. In 1938, Russian became a required subject of study in every Soviet school, including those in which a non-Russian language was the principal medium of instruction for other subjects (e.g., mathematics, science, and social studies). In 1939, non-Russian languages that had been given Latin-based scripts in the late 1920s were given new scripts based on the Cyrillic script. One likely rationale for these decisions was the sense of impending war and that Russian was the language of command in the Red Army.

Before and during World War II, Joseph Stalin deported to Central Asia and Siberia several entire nationalities for their suspected collaboration with the German invaders: Volga Germans, Crimean Tatars, Chechens, Ingush, Balkars, Kalmyks, and others. Shortly after the war, he deported many Ukrainians, Balts and Estonians to Siberia as well.[46]

After the war, the leading role of the Russian people in the Soviet family of nations and nationalities was promoted by Stalin and his successors. This shift was most clearly underscored by Communist Party General Secretary Stalin's Victory Day toast to the Russian people in May 1945:[47]

I would like to raise a toast to the health of our Soviet people and, before all, the Russian people. I drink, before all, to the health of the Russian people, because in this war they earned general recognition as the leading force of the Soviet Union among all the nationalities of our country.

Naming the Russian nation the primus inter pares was a total turnabout from Stalin's declaration 20 years earlier (heralding the korenizatsiya policy) that "the first immediate task of our Party is vigorously to combat the survivals of Great-Russian chauvinism." Although the official literature on nationalities and languages in subsequent years continued to speak of there being 130 equal languages in the USSR,[48] in practice a hierarchy was endorsed in which some nationalities and languages were given special roles or viewed as having different long-term futures.[49]

1958–59 education reform: parents choose language of instruction

An analysis of textbook publishing found that education was offered for at least one year and for at least the first class (grade) in 67 languages between 1934 and 1980.[50] However, the educational reforms undertaken after Nikita Khrushchev became First Secretary of the Communist Party in the late 1950s began a process of replacing non-Russian schools with Russian ones for the nationalities that had lower status in the federal system or whose populations were smaller or displayed widespread bilingualism already.[51] Nominally, this process was guided by the principle of "voluntary parental choice." But other factors also came into play, including the size and formal political status of the group in the Soviet federal hierarchy and the prevailing level of bilingualism among parents.[52] By the early 1970s schools in which non-Russian languages served as the principal medium of instruction operated in 45 languages, while seven more indigenous languages were taught as subjects of study for at least one class year. By 1980, instruction was offered in 35 non-Russian languages of the peoples of the USSR, just over half the number in the early 1930s.

Moreover, in most of these languages schooling was not offered for the complete 10-year curriculum. For example, within the RSFSR in 1958–59, full 10-year schooling in the native language was offered in only three languages: Russian, Tatar, and Bashkir.[53] And some nationalities had minimal or no native-language schooling. By 1962–1963, among non-Russian nationalities that were indigenous to the RSFSR, whereas 27% of children in classes I-IV (primary school) studied in Russian-language schools, 53% of those in classes V-VIII (incomplete secondary school) studied in Russian-language schools, and 66% of those in classes IX-X studied in Russian-language schools. Although many non-Russian languages were still offered as a subject of study at a higher class level (in some cases through complete general secondary school – the 10th class), the pattern of using the Russian language as the main medium of instruction accelerated after Khrushchev's parental choice program got under way.

Pressure to convert the main medium of instruction to Russian was evidently higher in urban areas. For example, in 1961–62, reportedly only 6% of Tatar children living in urban areas attended schools in which Tatar was the main medium of instruction.[53] Similarly in Dagestan in 1965, schools in which the indigenous language was the medium of instruction existed only in rural areas. The pattern was probably similar, if less extreme, in most of the non-Russian union republics, although in Belarus and Ukraine schooling in urban areas was highly Russianized.[54]

Doctrine catches up with practice: rapprochement and fusion of nations

The promotion of federalism and of non-Russian languages had always been a strategic decision aimed at expanding and maintaining rule by the Communist Party. On the theoretical plane, however, the Communist Party's official doctrine was that eventually nationality differences and nationalities as such would disappear. In official party doctrine as it was reformulated in the Third Program of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union introduced by Nikita Khrushchev at the 22nd Party Congress in 1961, although the program stated that ethnic distinctions would eventually disappear and a single common language would be adopted by all nationalities in the Soviet Union, "the obliteration of national distinctions, and especially language distinctions, is a considerably more drawn-out process than the obliteration of class distinctions." At that time, however, Soviet nations and nationalities were undergoing a dual process of further flowering of their cultures and of rapprochement or drawing together (сближение – sblizhenie) into a stronger union. In his Report on the Program to the Congress, Khrushchev used even stronger language: that the process of further rapprochement (sblizhenie) and greater unity of nations would eventually lead to a merging or fusion (слияние – sliyanie) of nationalities.[55]

Khrushchev's formula of rapprochement-fusing was moderated slightly, however, when Leonid Brezhnev replaced Khrushchev as General Secretary of the Communist Party in 1964 (a post he held until his death in 1982). Brezhnev asserted that rapprochement would lead ultimately to the complete "unity" of nationalities. "Unity" was an ambiguous term because it could imply either the maintenance of separate national identities but a higher stage of mutual attraction or similarity between nationalities, or the total disappearance of ethnic differences. In the political context of the time, "rapprochement-unity" was regarded as a softening of the pressure towards Russification that Khrushchev had promoted with his endorsement of sliyanie.

The 24th Party Congress in 1971, however, launched the idea that a new "Soviet people" was forming on the territory of the USSR, a community for which the common language – the language of the "Soviet people" – was the Russian language, consistent with the role that Russian was playing for the fraternal nations and nationalities in the territory already. This new community was labeled a people (народ – narod), not a nation (нация – natsiya), but in that context the Russian word narod ("people") implied an ethnic community, not just a civic or political community.

Thus, until the end of the Soviet era, doctrinal rationalization had been provided for some of the practical policy steps that were taken in the areas of education and the media. First of all, the transfer of many "national schools" (schools based on local languages) to Russian as a medium of instruction accelerated under Khrushchev in the late 1950s and continued into the 1980s.[56]

Second, the new doctrine was used to justify the special place of the Russian language as the "language of inter-nationality communication" (язык межнационального общения) in the USSR. Use of the term "inter-nationality" (межнациональное) rather than the more conventional "international" (международное) focused on the special internal role of Russian language rather than on its role as a language of international discourse. That Russian was the most widely spoken language, and that Russians were the majority of the population of the country, were also cited in justification of the special place of the Russian language in government, education, and the media.

At the 27th CPSU Party Congress in 1986, presided over by Mikhail Gorbachev, the 4th Party Program reiterated the formulas of the previous program:

Characteristic of the national relations in our country are both the continued flourishing of the nations and nationalities and the fact that they are steadily and voluntarily drawing closer together on the basis of equality and fraternal cooperation. Neither artificial prodding nor holding back of the objective trends of development is admissible here. In the long term historical perspective, this development will lead to complete unity of the nations.... The equal right of all citizens of the USSR to use their native languages and the free development of these languages will be ensured in the future as well. At the same time learning the Russian language, which has been voluntarily accepted by the Soviet people as a medium of communication between different nationalities, besides the language of one's nationality, broadens one's access to the achievements of science and technology and of Soviet and world culture.

Some factors favoring Russification

Progress in the spread of the Russian language as a second language and the gradual displacement of other languages was monitored in Soviet censuses. The Soviet censuses of 1926, 1937, 1939, and 1959, had included questions on "native language" (родной язык) as well as "nationality." The 1970, 1979, and 1989 censuses added to these questions one on "other language of the peoples of the USSR" that an individual could "use fluently" (свободно владеть). It is speculated that the explicit goal of the new question on the "second language" was to monitor the spread of Russian as the language of internationality communication.[57]

Each of the official homelands within the Soviet Union was regarded as the only homeland of the titular nationality and its language, while the Russian language was regarded as the language for interethnic communication for the whole Soviet Union. Therefore, for most of the Soviet era, especially after the korenizatsiya (indigenization) policy ended in the 1930s, schools in which non-Russian Soviet languages would be taught were not generally available outside the respective ethnically based administrative units of these ethnicities. Some exceptions appeared to involve cases of historic rivalries or patterns of assimilation between neighboring non-Russian groups, such as between Tatars and Bashkirs in Russia or among major Central Asian nationalities. For example, even in the 1970s schooling was offered in at least seven languages in Uzbekistan: Russian, Uzbek, Tajik, Kazakh, Turkmen, Kyrgyz, and Karakalpak.

While formally all languages were equal, in almost all Soviet republics the Russian/local bilingualism was "asymmetric": the titular nation learned Russian, whereas immigrant Russians generally did not learn the local language.

In addition, many non-Russians who lived outside their respective administrative units tended to become Russified linguistically; that is, they not only learned Russian as a second language but they also adopted it as their home language or mother tongue – although some still retained their sense of ethnic identity or origins even after shifting their native language to Russian. This includes both the traditional communities (e.g., Lithuanians in the northwestern Belarus (see Eastern Vilnius region) or the Kaliningrad Oblast (see Lithuania Minor)) and the communities that appeared during Soviet times such as Ukrainian or Belarusian workers in Kazakhstan or Latvia, whose children attended primarily the Russian-language schools and thus the further generations are primarily speaking Russian as their native language; for example, 57% of Estonia's Ukrainians, 70% of Estonia's Belarusians and 37% of Estonia's Latvians claimed Russian as the native language in the last Soviet census of 1989. Russian replaced Yiddish and other languages as the main language of many Jewish communities inside the Soviet Union as well.

Another consequence of the mixing of nationalities and the spread of bilingualism and linguistic Russification was the growth of ethnic intermarriage and a process of ethnic Russification—coming to call oneself Russian by nationality or ethnicity, not just speaking Russian as a second language or using it as a primary language. In the last decades of the Soviet Union, ethnic Russification (or ethnic assimilation) was moving very rapidly for a few nationalities such as the Karelians and Mordvinians.[58] However, whether children born in mixed families where one of the parents was Russian were likely to be raised as Russians depended on the context. For example, the majority of children in families where one parent was Russian and the other Ukrainian living in North Kazakhstan chose Russian as their nationality on their internal passport at age 16. However, children of mixed Russian and Estonian parents living in Tallinn (the capital city of Estonia), or mixed Russian and Latvian parents living in Riga (the capital of Latvia), or mixed Russian and Lithuanian parents living in Vilnius (the capital of Lithuania) most often chose as their own nationality that of the titular nationality of their republic – not Russian.[59]

More generally, patterns of linguistic and ethnic assimilation (Russification) were complex and cannot be accounted for by any single factor such as educational policy. Also relevant were the traditional cultures and religions of the groups, their residence in urban or rural areas, their contact with and exposure to the Russian language and to ethnic Russians, and other factors.[60]

Modern Russia

On 19 June 2018, the Russian State Duma adopted a bill that made education in all languages but Russian optional, overruling previous laws by ethnic autonomies, and reducing instruction in minority languages to only two hours a week.[61][62][63] This bill has been likened by some commentators, such as in Foreign Affairs, to a policy of Russification.[61]

When the bill was still being considered, advocates for minorities warned that the bill could endanger their languages and traditional cultures.[63][64] The law came after a lawsuit in the summer of 2017, where a Russian mother claimed that her son had been "materially harmed" by learning the Tatar language, while in a speech Putin argued that it was wrong to force someone to learn a language that is not their own.[63] The later "language crackdown" in which autonomous units were forced to stop mandatory hours of native languages was also seen as a move by Putin to "build identity in Russian society".[63]

Protests and petitions against the bill by either civic society, groups of public intellectuals or regional governments came from Tatarstan (with attempts for demonstrations suppressed),[65] Chuvashia,[63] Mari El,[63] North Ossetia,[65][66] Kabardino-Balkaria,[65][67] the Karachays,[65] the Kumyks,[65][68] the Avars,[65][69] Chechnya,[61][70] and Ingushetia.[71][61] Although the Duma representatives from the Caucasus did not oppose the bill,[61] it prompted a large outcry in the North Caucasus[65] with representatives from the region being accused of cowardice.[61] The law was also seen as possibly destabilizing, threatening ethnic relations and revitalizing the various North Caucasian nationalist movements.[61][63][65] The International Circassian Organization called for the law to be rescinded before it came into effect.[72] Twelve of Russia's ethnic autonomies, including five in the Caucasus called for the legislation to be blocked.[61][73]

On 10 September 2019, Udmurt activist Albert Razin self-immolated in front of the regional government building in Izhevsk as it was considering passing the controversial bill to reduce the status of the Udmurt language.[74] Between 2002 and 2010 the number of Udmurt speakers dwindled from 463,000 to 324,000.[75] Other languages in the Volga region recorded similar declines in the number of speakers; between the 2002 and 2010 censuses the number of Mari speakers declined from 254,000 to 204,000[64] while Chuvash recorded only 1,042,989 speakers in 2010, a 21.6% drop from 2002.[76] This is attributed to a gradual phasing out of indigenous language teaching both in the cities and rural areas while regional media and governments shift exclusively to Russian.

In the North Caucasus, the law came after a decade in which educational opportunities in the indigenous languages was reduced by more than 50%, due to budget reductions and federal efforts to decrease the role of languages other than Russian.[61][65] During this period, numerous indigenous languages in the North Caucasus showed significant decreases in their numbers of speakers even though the numbers of the corresponding nationalities increased, leading to fears of language replacement.[65][77] The numbers of Ossetian, Kumyk and Avar speakers dropped by 43,000, 63,000 and 80,000 respectively.[65] As of 2018, it has been reported that the North Caucasus is nearly devoid of schools that teach in mainly their native languages, with the exception of one school in North Ossetia, and a few in rural regions of Dagestan; this is true even in largely monoethnic Chechnya and Ingushetia.[65] Chechen and Ingush are still used as languages of everyday communication to a greater degree than their North Caucasian neighbours, but sociolinguistics argue that the current situation will lead to their degradation relative to Russian as well.[65]

In 2020, a set of amendments to the Russian constitution was approved by the State Duma[78] and later the Federation Council.[79] One of the amendments is to enshrine Russian as the “language of the state-forming nationality” and the Russian people as the ethnic group that created the nation.[80] The amendment has been met with criticism from Russia's minorities[81][82] who argue that it goes against the principle that Russia is a multinational state and will only marginalize them further.[83]

See also

- Derussianization

- Geographical distribution of Russian speakers

- Territorial evolution of Russia

- Dissolution of Russia

- Orthodoxy, Autocracy, and Nationality

- Education in the Soviet Union

- Slavophilia

- Population transfer in the Soviet Union

- Prometheism

- Citizenship of Russia

- Rashism

- Russophilia

- Russian imperialism

- Soviet people

- Soviet patriotism

- Colonialism

References

- Vernon V. Aspaturian, "The Non-Russian Peoples," in Allen Kassof, Ed., Prospects for Soviet Society (New York: Praeger, 1968): 143–198. Aspaturian also distinguished both Russianization and Russification from Sovietization, the process of spreading Soviet institutions and the Soviet socialist restructuring of social and economic relations in accordance with the ruling Communist Party's vision. (Aspaturian was a Soviet studies specialist, Evan Pugh Professor Emeritus of political science and former director of the Slavic and Soviet Language and Area Center at Pennsylvania State University.)

- Barbara A. Anderson and Brian D. Silver,"Demographic Sources of the Changing Ethnic Composition of the Soviet Union," Population and Development Review 15, No. 4 (Dec., 1989), pp. 609–656.

- Alexander Douglas Mitchell Carruthers, Jack Humphrey Miller (1914). Unknown Mongolia: a record of travel and exploration in north-west Mongolia and Dzungaria, Volume 2. Philadelphia: Lippincott. p. 345. Retrieved 29 May 2011.(Original from Harvard University)

- Dowling, Timothy C. (2 December 2014). Russia at War: From the Mongol Conquest to Afghanistan, Chechnya, and Beyond ... ISBN 9781598849486. Retrieved 23 April 2015.

- Humbatov, Tamara. Baku and the Germans: 1885 - 1887 years Archived 2011-07-19 at the Wayback Machine.

- Mamedov, N. education system in Azerbaijan Archived 2017-02-05 at the Wayback Machine.

- Azerbaijan in the second half of the nineteenth century Archived 2012-05-29 at the Wayback Machine.

- Aryeh Wasserman. «A Year of Rule by the Popular Front of Azerbaijan». Yaacov Ro'i (ed.). Muslim Eurasia: Conflicting Legaies. Routledge, 1995; p. 153

- Rumyantsev, Sergey. capital, a city or village. Results of urbanization in a separate taken in the South Caucasus republic.

- Mamardashvili, Merab. «The solar plexus" of Eurasia.

- Chertovskikh, Juliana and Lada Stativina . Azerbaijan lost Nasiba Zeynalova.

- Yunusov, Arif. Ethnic and migration processes in the post-Soviet Azerbaijan.

- Alexandre Bennigsen, S. Enders Wimbush. Muslims of the Soviet Empire. C. Hurst & Co. Publishers, 1985; with. 138

- Belarus has an identity crisis // openDemocracy

- Vadzim Smok. Belarusian Identity: the Impact of Lukashenka’s Rule // Analytical Paper. Ostrogorski Centre, BelarusDigest, 9 December 2013

- Галоўная бяда беларусаў у Беларусі — мова // Novy Chas (in Belarusian)

- Аляксандар Русіфікатар // Nasha Niva (in Belarusian)

- Thaden, Edward C., ed. (2014). Russification in the Baltic Provinces and Finland. Princeton: Princeton University Press. p. 58. ISBN 978-0691-615-29-5.

- Thaden, Edward C., ed. (2014). Russification in the Baltic Provinces and Finland. Princeton: Princeton University Press. p. 59. ISBN 978-0691-615-29-5.

- Grenoble, Lenore A. (2003). Language Policy in the Soviet Union. Dordrecht: Kluwer Academic Publishers. p. 204. ISBN 1-4020-1298-5.

- Loader, Michael (2016). "The Rebellious Republic: The 1958 Education Reform and Soviet Latvia" (PDF). Journal of the Institute of Latvian History. Riga: University of Latvia (3). ISBN 978-1-4020-1298-3.

- Gwertzman, Bernard (27 February 1972). "Protest on Soviet laid to Latvians". New York Times. Retrieved 31 July 2018.

- "The 17 Latvian Communist Protest Letter". letton.ch. Retrieved 31 July 2018.

- Zamoyski, Adam (2009). Poland: a history. Hammersmith: Harper Press. p. 228. ISBN 9780007282753.

- O'Connor, Kevin (2003). The History of the Baltic States. Greenwood Press. p. 58. ISBN 0-313-32355-0.

- Porter, Brian (2001). When Nationalism Began to Hate: Imagining Modern Politics in Nineteenth-Century Poland (PDF). Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-515187-9. Archived from the original (PDF) on 21 June 2010.

- Bideleux, Robert; Jeffries, Ian (1998). A History of Eastern Europe: Crisis and Change. Routledge. p. 185. ISBN 978-0415161114.

- "Archived copy" (PDF). www.aboutbooks.ru. Archived from the original (PDF) on 9 July 2016. Retrieved 12 January 2022.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - Szabaciuk, Andrzej (2013). "Rosyjski Ulster". Kwestia chełmska w polityce imperialnej Rosji w latach 1863–1915 (in Polish). KUL. p. 209. ISBN 978-83-7702-819-3.

- Ion Nistor / Istoria Basarabiei. Editie si studiu bio-bibliografic de Stelian Neagoe / Bucuresti, Editura HUMANITAS, 1991,

- "Short History of the Cyrillic Alphabet – Ivan G. Iliev – IJORS International Journal of Russian Studies". www.ijors.net.

- "Rights Group: Ukrainian Language Near Banished In Donbas Schools". RadioFreeEurope/RadioLiberty. 15 September 2019. Retrieved 17 December 2021.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - Saarikivi, Janne (2006). Substrata Uralica: Studies on Finno-Ugrian substrate in Northern Russian dialects (PhD thesis). ISBN 978-9949-11-474-0.

- Helimski, Eugene (2006). "The "Northwestern" Group of Finno-Ugric Languages and its Heritage in the Place Names and Substratum Vocabulary of the Russian North" (PDF). Slavica Helsingiensia. 27. Retrieved 10 August 2014.

- Rahkonen, Pauli (2011). "Finno-Ugrian hydronyms of the river Volkhov and Luga catchment areas" (PDF). Suomalais-Ugrilaisen Seuran Aikakauskirja. 2011 (93). doi:10.33340/susa.82436. S2CID 244880934. Retrieved 10 August 2014.

- Leinonen, Marja (2006). "The Russification of Komi" (PDF). Slavica Helsingiensia. 27. Retrieved 10 August 2014.

- Lallukka, Seppo (2008). "Venäjän valtakunnallinen ja suomalais-ugrilainen väestökriisi". In Saarinen, Sirkka; Herrala, Eeva (eds.). Murros: Suomalais-ugrilaiset kielet ja kulttuurit globalisaation paineessa. Uralica Helsingiensia (in Finnish). ISBN 978-952-5667-05-9. Retrieved 10 August 2014.

- Rouland 2004, p. 183.

- For a general timeline of Soviet policy towards the nationalities, see the Russian-language Wikipedia article on "Nationalities policy of Russia" (ru:Национальная политика России).

- Yuri Slezkine, "The USSR as a Communal Apartment, Or How a Socialist State Promoted Ethnic Particularism," Slavic Review 53, No. 2 (Summer 1994): 414–452.

- Rogers Brubaker, "Nationhood and the National Question in the Soviet Union and Post-Soviet Eurasia: An Institutionalist Account," Theory and Society 23 (February, 1994): 47–78.

- This was not focused simply on religion. In the Revolutionary and immediate post-Revolutionary period, after at first coöpting jadidist Tatar Sultan Galiyev into a leadership position in the Russian Communist Party (Bolsheviks), the Soviet regime soon turned to fight against his project and ideas for uniting Muslim peoples in a broader national liberal movement.

- See Slezkine (1994) and Ronald Wixman, Language Aspects of Ethnic Patterns and Processes in the North Caucasus, University of Chicago Geography Research Series, No. 19 (1980).

- Wixman (1980). One scholar has pointed out that the basic task of defining "what was a nationality" was assigned to ethnographers immediately after the formation of the USSR in 1924, and that they were asked to work quickly so that a population census could be taken with accounting by nationality. In contrast, the only complete imperial Russian census in 1897 did not use nationality at all as a category but instead used religion and language as ethnic markers. See Francine Hirsch, "The Soviet Union as a Work in Progress: Ethnographers and Category Nationality in the 1926, 1937, and 1939 Censuses," Slavic Review 56 (Summer 1997): 256–278.

- H. B. Paksoy, "Crimean Tatars," in Modern Encyclopedia of Religions in Russia and Soviet Union (Academic International Press, 1995), Vol. VI: 135–142.

- Robert Conquest, The Nation Killers: The Soviet Deportation of Nationalities (London: MacMillan, 1970) (ISBN 0-333-10575-3); S. Enders Wimbush and Ronald Wixman, "The Meskhetian Turks: A New Voice in Central Asia," Canadian Slavonic Papers 27, Nos. 2 and 3 (Summer and Fall, 1975): 320–340; and Alexander Nekrich, The Punished Peoples: The Deportation and Fate of Soviet Minorities at the End of the Second World War (New York: W. W. Norton, 1978) (ISBN 0-393-00068-0).

- This translation is drawn from CyberUSSR.com: http://www.cyberussr.com/rus/s-toast-r.html

- For example, M. I. Isaev, Сто тридцать равноправных; о языках народов СССР. [One hundred and thirty with equal rights; on languages of the peoples of the USSR]. Moscow: Nauka, 1970.

- In the specialized literature on sociolinguistics that evolved in the 1960s and later, scholars described such a hierarchy of societal functions by distinguishing Russian at the top of the hierarchy as the "language of inter-nationality communication," then the "national literary languages" of major Soviet nations (Ukrainian, Estonian, Uzbek, etc.), the "literary languages" of smaller nationalities and peoples (Chuvash, Mordvinian, etc.), and the languages of small ethnic groups. (See, inter alia, Yu. D. Desheriyev and I. F. Protchenko, Равитие языков народов СССР в советскую эпоху [Development of languages of the peoples of the USSR in the Soviet epoch]. Moscow: Prosveshchenie, 1968.) For an analysis by an American scholar of the different "functions" of major nationalities in the Soviet system of rule, see John A. Armstrong, "The Ethnic Scene in the Soviet Union: The View of the Dictatorship," in Erich Goldhagen, Ed., Ethnic Minorities in the Soviet Union (New York: Praeger, 1968): 3–49.

- On the differential and changing roles of Russian and the non-Russian languages in Soviet education over time see Barbara A. Anderson and Brian D. Silver, "Equality, Efficiency, and Politics in Soviet Bilingual Education Policy: 1934–1980," American Political Science Review 78 (December, 1984): 1019–1039.

- Yaroslav Bilinsky, "The Soviet Education Laws of 1958–59 and Soviet Nationality Policy," Soviet Studies 14 (Oct. 1962): 138–157.

- Brian D. Silver, "The Status of National Minority Languages in Soviet Education: An Assessment of Recent Changes," Soviet Studies 26 (Jan. 1974): 28–40; Isabelle Kreindler,"The Changing Status of Russian in the Soviet Union," International Journal of the Sociology of Language 33 (1982): 7–39; Anderson and Silver (1984).

- Silver (1974).

- Bilinsky (1962).

- Scholars often misattribute the endorsement of "sliyanie" to the Party Program. This word does not appear in the Party Program but only in Khrushchev's Report on the Program (his second speech at the Congress), though it did appear in officially approved literature about nationalities policy in subsequent years.

- See Anderson and Silver (1984). During this period, in most of the non-Russian official regions, the Ministry of Education distributed three main alternative school curricula, for: (1) Russian schools in which all subjects were taught in Russian, except for foreign (non-Soviet) languages; (2) "national schools" in which the native language was used as the main medium of instruction and Russian was taught as a subject of study (which might be termed the traditional national school); and (3) "national schools" in which Russian was the main medium of instruction and the native language was taught only as a separate subject (a new type of "national school" established after the 1958–59 education reforms). There were also some hybrid versions of the latter two types.

- Brian D. Silver, "The Ethnic and Language Dimensions in Russian and Soviet Censuses," in Ralph S. Clem, Ed., Research Guide to the Russian and Soviet Censuses (Ithaca: Cornell Univ. Press, 1986): 70–97.

- Barbara A. Anderson and Brian D. Silver, "Some Factors in the Linguistic and Ethnic Russification of Soviet Nationalities: Is Everyone Becoming Russian?" in Lubomyr Hajda and Mark Beissinger, Eds., The Nationality Factor in Soviet Politics and Society (Boulder: Westview, 1990): 95–130.

- For a summary of ethno-linguistic research conducted by Soviet scholars see Rasma Kārkliņa. 1986. Ethnic Relations in the USSR: The Perspective from Below (Boston and London: Allen & Unwin).

- Brian Silver, "Social Mobilization and the Russification of Soviet Nationalities," American Political Science Review 68 (March, 1974): 45–66; Brian D. Silver, "Language Policy and the Linguistic Russification of Soviet Nationalities," in Jeremy R. Azrael, Ed., Soviet Nationality Policies and Practices (New York: Praeger, 1978): 250–306.

- "Putin's Plan to Russify the Caucasus". Foreign Affairs. 1 August 2018.

- "Госдума приняла в первом чтении законопроект об изучении родных языков". RIA Novosti. 19 June 2018.

- "Russian minorities fear for languages amid new restrictions". Deutsche Welle. 5 December 2017.

- Coalson, Robert; Lyubimov, Dmitry; Alpaut, Ramazan (20 June 2018). "A Common Language: Russia's 'Ethnic' Republics See Language Bill As Existential Threat". Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty. Retrieved 9 August 2018.

- Kaplan, Mikail (31 May 2018). "How Russian state pressure on regional languages is sparking civic activism in the North Caucasus". Open Democracy. Archived from the original on 30 November 2018.

- "Тамерлан Камболов попросит Путина защитить осетинский язык". Gradus. 3 August 2018.

- "Кабардино-Балкария против законопроекта о добровольном обучении родным языкам". 23 April 2018.

- "Кумыки потребовали снять с повестки дня Госдумы законопроект о добровольном изучении языков". Idel Real. 10 May 2018.

- "В Хасавюрте прошёл митинг в поддержку преподавания родного языка". Idel Real. 15 May 2018.

- "Чеченские педагоги назвали факультативное изучение родного языка неприемлемым". Kavkaz Uzel. 30 July 2018.

- "Общественники Ингушетии: законопроект о языках – "циничная дискриминация народов"". Kavkaz Realii. 12 June 2018.

- "Международная черкесская ассоциация призвала заблокировать закон о родных языках". Kavkaz Uzel. 5 July 2018.

- "Представители нацреспублик России назвали закон о родных языках антиконституционным". Kavkaz Uzel. 1 July 2018.

- "Russian Scholar Dies From Self-Immolation While Protesting to Save Native Language". The Moscow Times. 10 September 2019. Retrieved 11 September 2019.

- "Man Dies After Self-Immolation Protest Over Language Policies in Russia's Udmurtia". Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty. 10 September 2019. Retrieved 11 September 2019.

- Blinov, Alexander (10 June 2022). "Alexander Blinov: "In state structures, the Chuvash language most often performs a symbolic function"". Realnoe Vremya (in Russian). Retrieved 5 July 2022.

- "Живой на бумаге".

- Seddon, Max; Foy, Henry (10 March 2020). "Kremlin denies Russia constitution rewrite is Putin power grab". Financial Times. Retrieved 11 March 2020.

- "Russian Lawmakers Adopt Putin's Sweeping Constitutional Amendments". The Moscow Times. 11 March 2020. Retrieved 11 March 2020.

- Budryk, Zack (3 March 2020). "Putin proposes gay marriage constitutional ban in Russia". The Hill. Retrieved 11 March 2020.

- Jalilov, Rustam (11 March 2020). "Amendment to state-forming people faces criticism in the North Caucasus". Caucasian Knot (in Russian). Retrieved 11 March 2020.

- Alpout, Ramadan (10 March 2020). ""We are again foreigners, but now officially." Amendment to the constituent people". Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty (in Russian). Retrieved 11 March 2020.

- Rakhmatullin, Timur (5 March 2020). "Who to benefit from 'Russian article' in the Constitution?". Realnoe Vremya. Retrieved 11 March 2020.

Further reading

- Anderson, Barbara A., and Brian D. Silver. 1984. "Equality, Efficiency, and Politics in Soviet Bilingual Education Policy: 1934–1980," American Political Science Review 78 (December): 1019–1039.

- Armstrong, John A. 1968. "The Ethnic Scene in the Soviet Union: The View of the Dictatorship," in Erich Goldhagen, Ed., Ethnic Minorities in the Soviet Union (New York: Praeger): 3–49.

- Aspaturian, Vernon V. 1968. "The Non-Russian Peoples," in Allen Kassof, Ed., Prospects for Soviet Society. New York: Praeger: 143–198.

- Azrael, Jeremy R., Ed. 1978. Soviet Nationality Policies and Practices. New York: Praeger.

- Włodzimierz Bączkowski (1958). Russian colonialism: the Tsarist and Soviet empires. New York, Frederick A. Praeger. p. 97.

- Bilinsky, Yaroslav. 1962. "The Soviet Education Laws of 1958–59 and Soviet Nationality Policy," Soviet Studies 14 (Oct. 1962): 138–157.

- Carrère d'Encausse, Hélène (1992). Grand défi (Grand Defile; Bolsheviks and Nations 1917–1930). Warsaw, Most. p. 186.

- Conquest, Robert (1977). The nation killers. Houndmills, Macmillan Press. p. 222. ISBN 0-333-10575-3.

- Andrzej Chwalba (1999). Polacy w służbie Moskali (Poles in the Muscovite Service). Kraków, PWN. p. 257. ISBN 83-01-12753-8.

- Gross, J. T. (2000). Revolution from abroad; the soviet conquest of Poland's western Ukraine and western Belorussia. Princeton, Princeton University Press. p. 396. ISBN 0-691-09603-1.

- Gasimov, Zaur (Ed.), Kampf um Wort und Schrift. Russifizierung in Osteuropa im 19.-20. Jahrhundert. Göttingen:V&R 2012.

- Hajda, Lubomyr, and Mark Beissinger, Eds. 1990. The Nationality Factor in Soviet Politics and Society. Boulder, CO: Westview.

- Kaiser, Robert, and Jeffrey Chinn. 1996. The Russians as the New Minority in the Soviet Successor States. Boulder, CO: Westview.

- Karklins, Rasma. 1986. Ethnic Relations in the USSR: The Perspective from Below. Boston and London: Allen & Unwin.

- Kreindler, Isabelle. 1982. "The Changing Status of Russian in the Soviet Union," International Journal of the Sociology of Language 33: 7–39.

- Lewis, E. Glyn. 1972. Multilingualism in the Soviet Union: Aspects of Language Policy and its Implementation. The Hague: Mouton.

- Pavlenko, Aneta. 2008. Multilingualism in Post-Soviet Countries. Multilingual Matters, Tonawanda, NY. ISBN 1-84769-087-4.

- Rodkiewicz, Witold (1998). Russian nationality policy in the Western provinces of the Empire (1863–1905). Lublin, Scientific Society of Lublin. p. 295. ISBN 83-87833-06-1.

- Rouland, Michael (2004). "A nation on stage: music and the 1936 Festival of Kazak Arts". In Neil Edmunds, ed., Soviet Music and Society under Lenin and Stalin: The baton and sickle (pp. 181–208). Abingdon & New York, NY: RoutledgeCurzon. ISBN 978-0-415-30219-7.

- Serbak, Mykola (1997). Natsional'na politika tsarizmu na pravoberežniy Ukrayni (National Politics of Tsardom in Right-bank Ukraine). Kyiv, Kyiv Shevchenko University Press. p. 89. ISBN 5-7763-9036-2.

- Silver, Brian D. 1974. "The Status of National Minority Languages in Soviet Education: An Assessment of Recent Changes," Soviet Studies 26 (January): 28–40.

- Silver, Brian D. 1986. "The Ethnic and Language Dimensions in Russian and Soviet Censuses," in Ralph S. Clem, Ed., Research Guide to the Russian and Soviet Censuses (Ithaca: Cornell Univ. Press): 70–97.

- Leonard Szymański (1983). Zarys polityki caratu wobec szkolnictwa ogólnokształcącego w Królestwie Polskim w latach 1815–1915 (Sketch of the Tsarist Politics Regarding General Education in the Kingdom of Poland Between 1815 and 1915). Wrocław, AWF. p. 1982.

- Thaden, Edward C., Ed. 1981. Russification in the Baltic Provinces and Finland, 1855–1914. Princeton: Princeton University Press. ISBN 0-691-05314-6

- Weeks, Theodore R. (1996). Nation and state in late Imperial Russia: nationalism and Russification on the western frontier, 1863–1914. DeKalb, Northern Illinois University Press. p. 297. ISBN 0-87580-216-8.

- Weeks, Theodore R. (2001). "Russification and the Lithuanians, 1863–1905". Slavic Review. 60 (1): 96–114. doi:10.2307/2697645. JSTOR 2697645. S2CID 163956911.

- Weeks, Theodore R. (2004). "Russification: Word and Practice 1863–1914" (PDF). Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society. 148 (4): 471–489. Archived from the original (PDF) on 23 May 2012.

- Weeks, Theodore R. (2011). Russification / Sovietization. Institute of European History.

- Wixman, Ronald. 1984. The Peoples of the USSR: An Ethnographic Handbook. New York: M.E. Sharpe and London, Macmillan.

- John Morison, ed. (2000). Ethnic and national issues in Russian and East European history; selected papers from the Fifth World Congress of Central and East European Studies. Houndmills, Basingstoke, Macmillan Press; New York, St. Martin's Press. p. 337. ISBN 0-333-69550-X.

- Problemy natsional'nogo soznaniâ pol'skogo naseleniâ na Belarusi (Problems of National Identity of Poles in Belarus). Grodno, Society of Poles in Belarus. 2003. p. 288.

External links

- Russification in Lithuania

- LTV online documentary examines 'Russification' and its effects. 16 April 2020. Public Broadcasting of Latvia.

- The Civic Identity of Russifying Officials in the Empire’s Northwestern Region after 1863 by Mikhail Dolbilov

- Permanent mission of Caucasian Institute for Democracy Foundation opened in Tskhinvali – Regnum News Agency (Russia), 9 December 2005

- Tatarstan Rejects Dominant Role of Russians – Kommersant, 6 March 2006

- Forgetting How to Speak Russian | Fast forward | OZY (7 January 2014)