Shrewsbury

Shrewsbury (/ˈʃroʊzb(ə)ri/ (![]() listen) SHROHZ-b(ə)ree, also /ˈʃruːz-/ (

listen) SHROHZ-b(ə)ree, also /ˈʃruːz-/ (![]() listen) SHROOZ-)[4][5][6] is a market town and the county town of Shropshire, England, on the River Severn, 150 miles (240 km) north-west of London; at the 2011 census, it had a population of 71,715.[3][7]

listen) SHROOZ-)[4][5][6] is a market town and the county town of Shropshire, England, on the River Severn, 150 miles (240 km) north-west of London; at the 2011 census, it had a population of 71,715.[3][7]

Shrewsbury | |

|---|---|

County town | |

Clockwise from top: Shrewsbury skyline, Shrewsbury Castle, English Bridge and The Square | |

Flag  Coat of arms | |

| Motto(s): Floreat Salopia ("May Shrewsbury Flourish") | |

Shrewsbury Shrewsbury shown within Shropshire and England | |

| Coordinates: 52.708°N 2.754°W | |

| Sovereign state | United Kingdom |

| Constituent country | England |

| Region | West Midlands |

| Ceremonial county | Shropshire |

| Local government | Shropshire |

| Founded | c. 9th century |

| Market charter | 1189 |

| Administrative HQ | Riggs Hall[1] |

| Government | |

| • Type | Town council |

| • Governing body | Shrewsbury Town Council[2] |

| • UK Parliament | Shrewsbury and Atcham |

| Elevation | 233 ft (71 m) |

| Population (2011) | |

| • Total | 71,715 [3] |

| Demonym | Salopian |

| Time zone | GMT |

| • Summer (DST) | BST |

| Post codes | SY1, SY2, SY3 |

| Area code | 01743 |

| Police Force | West Mercia Police |

| Fire Service | Shropshire Fire |

| Ambulance Service | West Midlands |

The town centre has a largely unspoilt medieval street plan and over 660 listed buildings,[8] including several examples of timber framing from the 15th and 16th centuries. Shrewsbury Castle, a red sandstone fortification, and Shrewsbury Abbey, a former Benedictine monastery, were founded in 1074 and 1083 respectively by the Norman Earl of Shrewsbury, Roger de Montgomery.[9] The town is the birthplace of Charles Darwin and is where he spent 27 years of his life.[10]

9 miles (14 km) east of the Welsh border, Shrewsbury serves as the commercial centre for Shropshire and mid-Wales, with a retail output of over £299 million per year and light industry and distribution centres, such as Battlefield Enterprise Park, on the outskirts. The A5 and A49 trunk roads come together as the town's by-pass and five railway lines meet at Shrewsbury railway station.

History

Early history

The town was the early capital of the Kingdom of Powys,[11] known to the ancient Britons as Pengwern, signifying "the alder hill";[12] and in Old English as Scrobbesburh (dative Scrobbesbyrig), which may mean either "Scrobb's fort" or "the fortified place in the bushes" (or "shrubs", the modern derivate).[13] This name gradually evolved in three directions, into Sciropscire, which became Shropshire; into Sloppesberie, which became Salop / Salopia (an alternative name for both town and county), and into Schrosberie, which eventually became the town's name, Shrewsbury.[12] Its later Welsh name Amwythig means "fortified place".[14]

Over the ages, the geographically important town has been the site of many conflicts, particularly between the English and Welsh. The Angles, under King Offa of Mercia, took possession in 778.[15]

Nearby is the village of Wroxeter, 5 miles (8 km) to the south-east. This was once the site of Viroconium, the fourth largest cantonal capital in Roman Britain. As Caer Guricon it is a possible alternative for the Dark Age seat of the Kingdom of Powys.[16] The importance of the Shrewsbury area in the Roman era was underlined with the discovery of the Shrewsbury Hoard in 2009.[17][18]

Medieval

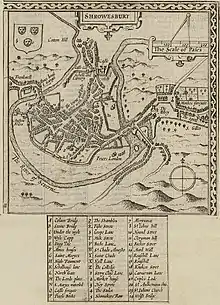

Shrewsbury's known history commences in the Early Middle Ages, having been founded c. 800 AD. It is believed that Anglo-Saxon Shrewsbury was most probably a settlement fortified through the use of earthworks comprising a ditch and rampart, which were then shored up with a wooden stockade.[20] There is evidence to show that by the beginning of the 900s, Shrewsbury was home to a mint.[20]

Roger de Montgomery was given the town as a gift from William, and built Shrewsbury Castle in 1074,[9] taking the title of Earl. He founded Shrewsbury Abbey as a Benedictine monastery in 1083.[21] The 3rd Earl, Robert of Bellême, was deposed in 1102 and the title forfeited, in consequence of rebelling against Henry I and joining the Duke of Normandy's invasion of England in 1101.[12] In 1138, King Stephen successfully besieged the castle held by William FitzAlan for the Empress Maud during the period known as the Anarchy.[22]

From 1155, during the reign of Henry II, there was a leper hospital dedicated to St Giles and associated with Shrewsbury Abbey. From the 1220s, there was also a general hospital dedicated to St John the Baptist.[23]

In 1283, Edward I summoned a parliament in Shrewsbury (later adjourned to Acton Burnell[24]) to try and condemn David III, last of the independent native line of Princes of Wales, to execution by hanging, drawing and quartering within the town after David was captured, ending his rebellion against the King.[25]

It was in the late Middle Ages (14th and 15th centuries) when the town was at its height of commercial importance. This success was mainly due to wool production, a major industry at the time, and the wool trade with the rest of Britain and Europe, with the River Severn and Watling Street acting as trading routes.[26] The Shrewsbury Drapers Company dominated the trade in Welsh wool for many years.[27]

In the midst of its commercial success, Shrewsbury was devastated by the Black Death, which records suggest arrived in the spring of 1349.[28] Examining the number of local church benefices falling vacant due to death, 1349 alone saw twice as many vacancies as the previous ten years combined, suggesting a high death toll in Shrewsbury.[29]

In 1403 the Battle of Shrewsbury was fought a few miles north of the town centre, at Battlefield; it was fought between King Henry IV and Henry Hotspur Percy, with the King emerging victorious,[30] an event celebrated in William Shakespeare's Henry IV, Part 1, Act 5.[31]

Early modern

Shrewsbury's monastic gathering was disbanded with the Dissolution of the Monasteries and as such the Abbey was closed in 1540. However, it is believed that Henry VIII thereafter intended to make Shrewsbury a cathedral city after the formation of the Church of England, but the citizens of the town declined the offer. Despite this, Shrewsbury thrived throughout the 16th and 17th centuries; largely due to the town's fortuitous location, which allowed it to control the Welsh wool trade. As a result, a number of grand edifices, including the Ireland's Mansion (built 1575) and Draper's Hall (1658), were constructed. It was also in this period that Edward VI gave permission for the foundation of a free school, which was later to become Shrewsbury School.

The monastic hospitals, and incomes from their endowments, were transferred to secular owners. St Giles leper hospital passed to the Prince family, later Earls of Tankerville. St John the Baptist hospital passed to the Wood family, and became almshouses.[23]

During the English Civil War, the town was a Royalist stronghold and only fell to Parliament forces after they were let in by a parliamentarian sympathiser at the St Mary's Water Gate (now also known as Traitor's Gate). After Thomas Mytton captured Shrewsbury in February 1645; in following with the ordnance of no quarter; a dozen Irish prisoners were selected to be killed after picking lots.[32][33] This prompted Prince Rupert to respond by executing Parliamentarian prisoners in Oswestry.

Shrewsbury Unitarian Church was founded in 1662. By the 18th century Shrewsbury had become an important market town and stop off for stagecoaches travelling between London and Holyhead on their way to Ireland; this led to the establishment of a number of coaching inns, many of which, such as the Lion Hotel, are extant to this day.

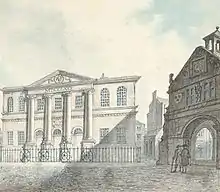

A town hall was built in the Market Place on the site of an ancient guildhall in 1730;[34] it was demolished and a new combined guildhall and shirehall was erected on the site in 1837.[35]

Local soldier and statesman Robert Clive was Shrewsbury's MP from 1762 until his death in 1774; Clive also served once as the town's mayor in 1762.[36]

St Chad's Church collapsed in 1788 after attempts to expand the crypt compromised the structural integrity of the tower above. Now known as Old St Chad's, the remains of the church building and its churchyard are on the corner of Princess Street, College Hill and Belmont. A new St Chad's Church was built just four years after the collapse, but as a large neo-classical round church and in a different and more elevated location, at the top of Claremont Hill close to The Quarry.[20]

In the period directly after Napoleon's surrender after Waterloo (18 June 1815), the town's own 53rd (Shropshire) Regiment of Foot was sent to guard him in his exile on St Helena. A locket containing a lock of the emperor's hair (presented to an officer of the 53rd) remains to this day in the collections of the Shropshire Regimental Museum at Shrewsbury Castle.[37]

Late modern

The town is home to the Ditherington Flax Mill, completed in 1797, the world's first iron-framed building, which is commonly regarded as "the grandfather of the skyscraper". Its importance was officially recognised in the 1950s, resulting in it becoming a Grade I listed building.[38][39] Shrewsbury in the Industrial Revolution was on the Shrewsbury Canal (operating by 1797) which linked it with the Shropshire Canal and the rest of the canal network of Great Britain.[40]

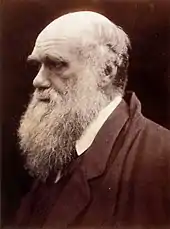

Shrewsbury has played a part in Western intellectual history, by being the town where the naturalist Charles Darwin was born in 1809 and brought up.[41]

The town suffered very little from air raids in the Second World War, the worst case in Shrewsbury was in 1940, a woman and her two grandchildren were killed when a cottage was destroyed on Ellesmere Road, the only local air raid deaths.[42] Therefore, many of its ancient buildings remain intact and there was little redevelopment in the 1960s and 1970s, which arguably destroyed the character of many historic towns in the UK. However, some historic buildings were demolished to make way for the brutalist architectural style of the 1960s, though the town was saved from a new 'inner ring road' due to its challenging geography.[43] A notable example of 1960s/70s construction in Shrewsbury was Telecom House on Smithfield Road, demolished in the 2000s.[44]

The town was targeted by the IRA in 1992. One bomb detonated within the grounds of Shrewsbury Castle causing severe damage to the regimental museum of the Shropshire Light Infantry.[45] The damage caused was estimated to be in the region of £250,000 and many irreplaceable artefacts were lost. A second bomb detonated in the Darwin Shopping Centre but was put out by the sprinkler system before any major damage was caused. Finally, a third bomb was discovered elsewhere in the town centre but failed to do any damage.[46]

From the late 1990s, the town experienced severe flooding problems from the Severn and Rea Brook. In the autumn of 2000 large swathes of the town were underwater, notably Frankwell, which flooded three times in six weeks.[47] The Frankwell flood defences were completed in 2003, along with the new offices of Shrewsbury and Atcham Borough Council. More recently, such as in 2005 and 2007 but not 2020, flooding has been less severe, and the defences have generally held back floodwaters from the town centre areas. However, the town car parks are often left to be flooded in the winter, which reduces trade in the town, most evidenced in the run up to Christmas in 2007.[48]

Shrewsbury won the West Midlands Capital of Enterprise award in 2004.[49] The town has two large expanding business parks, Shrewsbury Business Park by the A5 in the southeast and Battlefield Enterprise Park in the north. There are many residential developments currently under construction in the town to cater for the increasing numbers of people wishing to live in the town, which is a popular place to commute to Telford, Wolverhampton and Birmingham from.[50]

A 2005 report on prison population found that HM Prison Shrewsbury was the most overcrowded in England and Wales.[51] The prison, which was also known as the Dana, was closed in 2013 and then sold by the Ministry of Justice to private property developers in 2014.[52]

In 2009 Shrewsbury Town Council was formed and the town's traditional coat of arms was returned to everyday use.[53]

Geography

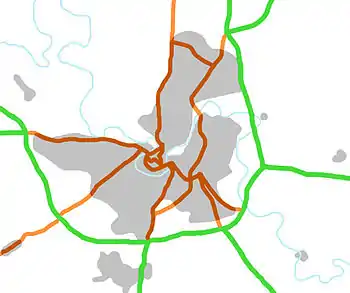

Shrewsbury is about 14 miles (23 km) west of Telford, 43 miles (69 km) west of Birmingham and the West Midlands Conurbation, and about 153 miles (246 km) north-west of the capital, London. More locally, the town is to the east of Welshpool, with Bridgnorth and Kidderminster to the south-east. The border with Wales is 9 miles (14 km) to the west. The town centre is partially built on a hill whose elevation is, at its highest, 246 feet (75 m) above sea level. The longest river in the UK, the River Severn, flows through the town, forming a meander around its centre.[12] The town is subject to flooding from the river.

Atcham

Bayston Hill

Hanwood

Bicton

Upton

Magna A5 (TELFORD) ->

Uffington

Abbey Foregate

TC

Underdale

Belvidere

Monkmoor

Belle Vue

Meole Brace

Sutton Farm

Emstrey

Kingsland

Porthill

Frankwell

Shelton

Bicton

Heath Copthorne

Radbrook

Nobold

Castlefields

Bagley

Ditherington

Harlescott

Sundorne

Battlefield

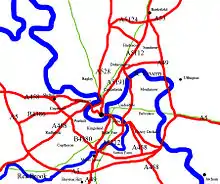

A clickable link map of Shrewsbury showing suburbs and surrounding villages.

|

The town is near Haughmond Hill, a site where Precambrian rocks, some of the oldest rocks in the county can be found,[54] and the town itself is sited on an area of largely Carboniferous rocks.[55] A fault, the Hodnet Fault, starts approximately at the town, and runs as far as Market Drayton.

Suburbs

There are a number of suburbs and surrounding villages. The River Severn separates the western, southern and eastern suburbs from the town centre and northern suburbs. An example of a large neighbouring village that has effectively become part of the suburban area is Bayston Hill, which grew considerably in the latter half of the 20th century and is now separated from the Meole Brace suburb by only a few fields and the A5 by-pass. It remains, however, a separate entity to the town, with its own parish council, etc. Bayston Hill lies 3 miles (5 km) south of the town centre of Shrewsbury and on the A49 and near to the A5.[56] The smaller village of Battlefield, north of the town, is considered a suburb of Shrewsbury. It is covered by the parish of Shrewsbury.[57]

Climate

The climate of Shrewsbury is similar to that of the rest of Shropshire, generally moderate. Rainfall averages 76 to 100 cm (30 to 39 in), influenced by being in the rainshadow of the Cambrian Mountains from warm, moist frontal systems of the Atlantic Ocean, which bring generally light precipitation in autumn and spring.[58] The nearest weather station is at Shawbury, about 6.5 miles (10.5 km) north-east of Shrewsbury town centre. The local topography, being that of a low-lying plain surrounded by higher ground to the west, south and east gives the Shrewsbury area its own microclimate – the absolute maximum at Shawbury of 34.9 °C (94.8 °F) and absolute minimum of −25.2 °C (−13.4 °F) represents the largest temperature range of any individual weather station in the British Isles – although the maximum range of average temperatures tends to peak to the south east of the Shrewsbury area, particularly in the south east midlands, inland East Anglia and inland south east England.

In an average year, the warmest day is 28.4 °C (83.1 °F),[59] giving a total of 8.9 days[60] of 25.1 °C (77.2 °F) or above. The absolute maximum of 34.9 °C (94.8 °F)[61] was recorded in August 1990.

Conversely, the coldest night of the year typically falls to −9.6 °C (14.7 °F)[62] – in total 61.7 air frosts are recorded in an average year. The absolute minimum of −25.2 °C (−13.4 °F)[63] was recorded in 1981.

Annual average rainfall averages around 650 mm, with over 1 mm falling on 124 days of the year.

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Record high °C (°F) | 14.6 (58.3) |

17.4 (63.3) |

21.5 (70.7) |

25.2 (77.4) |

26.7 (80.1) |

31.2 (88.2) |

35.7 (96.3) |

34.9 (94.8) |

29.6 (85.3) |

28.1 (82.6) |

18.4 (65.1) |

15.4 (59.7) |

35.7 (96.3) |

| Average high °C (°F) | 7.5 (45.5) |

8.1 (46.6) |

10.3 (50.5) |

13.2 (55.8) |

16.3 (61.3) |

19.1 (66.4) |

21.1 (70.0) |

20.7 (69.3) |

18.1 (64.6) |

14.2 (57.6) |

10.3 (50.5) |

7.7 (45.9) |

13.9 (57.0) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 4.3 (39.7) |

4.6 (40.3) |

6.3 (43.3) |

8.6 (47.5) |

11.5 (52.7) |

14.4 (57.9) |

16.3 (61.3) |

16.0 (60.8) |

13.7 (56.7) |

10.4 (50.7) |

6.9 (44.4) |

4.5 (40.1) |

9.8 (49.6) |

| Average low °C (°F) | 1.2 (34.2) |

1.2 (34.2) |

2.3 (36.1) |

3.9 (39.0) |

6.8 (44.2) |

9.6 (49.3) |

11.5 (52.7) |

11.4 (52.5) |

9.3 (48.7) |

6.6 (43.9) |

3.5 (38.3) |

1.3 (34.3) |

5.7 (42.3) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −21.4 (−6.5) |

−12.9 (8.8) |

−12.2 (10.0) |

−5.9 (21.4) |

−3.3 (26.1) |

−0.5 (31.1) |

2.5 (36.5) |

0.8 (33.4) |

−2.5 (27.5) |

−5.9 (21.4) |

−12.5 (9.5) |

−25.2 (−13.4) |

−25.2 (−13.4) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 57.4 (2.26) |

43.3 (1.70) |

43.4 (1.71) |

47.1 (1.85) |

53.6 (2.11) |

59.0 (2.32) |

57.6 (2.27) |

64.2 (2.53) |

61.1 (2.41) |

68.8 (2.71) |

60.8 (2.39) |

66.3 (2.61) |

682.5 (26.87) |

| Average snowfall mm (inches) | 26 (1.0) |

19 (0.7) |

3 (0.1) |

4 (0.2) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

1 (0.0) |

27 (1.1) |

80 (3.1) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 1.0 mm) | 12.1 | 10.8 | 10.2 | 10.4 | 10.0 | 10.1 | 10.5 | 10.5 | 10.0 | 11.3 | 12.5 | 13.1 | 131.6 |

| Average snowy days | 3.0 | 2.9 | 1.1 | 0.3 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.2 | 1.6 | 9.1 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 90 | 87 | 84 | 83 | 82 | 84 | 83 | 83 | 86 | 88 | 90 | 90 | 86 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 52.8 | 74.9 | 114.6 | 158.1 | 194.9 | 187.5 | 193.3 | 168.0 | 134.7 | 97.5 | 61.8 | 49.9 | 1,487.8 |

| Mean daily daylight hours | 8.3 | 9.9 | 11.9 | 14.0 | 15.8 | 16.8 | 16.3 | 14.7 | 12.7 | 10.6 | 8.7 | 7.7 | 12.3 |

| Average ultraviolet index | 2 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 3 |

| Source 1: Met Office[64] European Climate Assessment and Dataset[65] | |||||||||||||

| Source 2: WeatherAtlas[66] | |||||||||||||

Government

The Borough of Shrewsbury's first Charter was granted by King Henry I allowing the collection of rents. King Richard I granted another early charter in 1189 and from that time the town's regional importance and influence increased, as well as its autonomy from the county of Shropshire. Further charters were granted in 1199 (King John), 1495 (Henry VII), 1638 (Charles I) and 1685 (James II). In 1974 a charter from the Queen incorporated the Borough of Shrewsbury and Atcham, under the auspices of which the town remained until 2009.[68]

Shrewsbury is the administrative centre for the new Shropshire Council, the unitary authority covering most of Shropshire (but excluding the Borough of Telford and Wrekin, a separate unitary authority area). Shropshire Council have their headquarters at the Shirehall, on Abbey Foregate.[69]

Shrewsbury is in the Shrewsbury and Atcham constituency and is the only large settlement in the constituency. At the most recent general election, in 2019, Daniel Kawczynski of the Conservative Party was elected with a majority of 11,217. Previous MPs for Shrewsbury have included 19th century Prime Minister Benjamin Disraeli.[70]

Shrewsbury has been twinned with Zutphen, Netherlands since 1977.[71] The Royal Navy submarine HMS Talent is affiliated with Shrewsbury and the town also served as the administrative headquarters of the British Army's regional 143 (West Midlands) Brigade whose administrative HQ was based at Copthorne Barracks, until 2014.[72]

Town Council

| Shrewsbury Town Council | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Year | Lab | Lib | Con | Grn | ||||

| 2009 | 3 | 2 | 12 | 0 | ||||

| 2010* | 4 | 2 | 11 | 0 | ||||

| 2012* | 4 | 3 | 10 | 0 | ||||

| 2013 | 7 | 5 | 5 | 0 | ||||

| 2017 | 7 | 3 | 6 | 1 | ||||

| 2021 | 7 | 6 | 2 | 2 | ||||

| The changing political make-up of the town council. * = by-election | ||||||||

Shrewsbury was until 2009 an unparished area and had no town or parish council(s). Instead, the Mayor of Shrewsbury and Atcham, based at the Guildhall in Dogpole,[73] was also the mayor of the town. However, as part of wider changes to local governance in Shropshire, the town was parished on 13 May 2008, with a single parish created covering the entire town and previously unparished area. Shrewsbury is the second most populous civil parish in England (only Weston-super-Mare has a greater population) with a population of approximately 72,000. The area of the parish is 3,799 hectares (9,390 acres).

The town council, which is the parish council, first convened on 1 April 2009, and its chair is the Mayor of Shrewsbury. For the interim period before the first elections, the existing county councillors who represented electoral divisions covering Shrewsbury were the town councillors. On 4 June 2009, the first election was held to the town council, with councillors elected from 17 single-member wards coterminous with Shropshire Council electoral divisions.

The political make-up of the town council, as of the 2021 local elections, sees Labour as the largest party with 7 seats, the Liberal Democrats with 6, the Conservatives with 2 and the Green Party with 2. The Mayor of Shrewsbury for 2018–19 is Peter Nutting.[74]

The town council was based at the Guildhall on Frankwell Quay, a facility which had originally been built in 2004 as the headquarters of Shrewsbury and Atcham Borough Council; however the town council moved to Riggs Hall in 2017.[75] Riggs Hall is one of the original buildings on the former site of Shrewsbury School on Castle Gates (to the rear of the town's main library).[76]

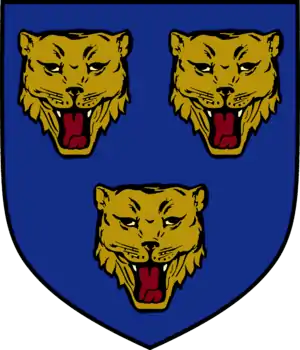

Coat of arms

The coat of arms of the former Shrewsbury Borough Council, and now the Town Council, depicts three loggerheads (leopards), with the motto Floreat Salopia, a Latin phrase that can be translated to "May Shrewsbury Flourish".[77][78] The coat of arms of the (now abolished) Shrewsbury and Atcham Borough Council was Shrewsbury's shield with the addition of Atcham Bridge running above the leopards. Shrewsbury Town F.C. historically used the leopard, but from 1986 till 1992 had a Celtic shrew and from 2007 to 2015 had a badge depicting a lion rather than a leopard. A new leopard badge embedded in a circular shape returned for 2015–16 season. The flag of Shropshire, and other county crests etc., also uses the three loggerheads.

Demography

| Shrewsbury and Atcham Compared | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| 2001 UK Census | S'bury & Atch. | West Midlands | England |

| Total population | 95,850 | 5,267,308 | 49,138,831 |

| White | 98.5% | 86.2% | 87.0% |

| Asian | 0.4% | 7.3% | 4.6% |

| Black | 0.1% | 2.0% | 2.3% |

| Over 65 years old | 17.2% | 16.0% | 15.9% |

| Christian | 77.9% | 72.6% | 71.7% |

| No Religion | 13.7% | 12.3% | 14.6% |

According to the United Kingdom Census 2001, the population of the town of Shrewsbury was 67,126.[79] The same census put the population of the wider (and now abolished) borough of Shrewsbury and Atcham at 95,850.[79] In 1981 the population of the town was 57,731 and in 1991 the population of the town was 64,219.[80] Shrewsbury is Shropshire's second largest town, after Telford.

The 2001 census indicates that the population of the town consists of 51.1% females, and 48.9% males, which echoes the trend of Shrewsbury and Atcham borough, and that of Shropshire as a whole.[81] According to the same census, the ethnic composition of the town is largely white, at 98.5% of the total population. The next largest ethnic group is mixed race, at 0.5% of the town's population. 0.4% of the population is Indian, Pakistani or Bangladeshi, and 0.1% of the population is South Asian or British Asian. A further 0.1% is Black, Caribbean or African.[81]

Historical population

The population figures below are for the borough of Shrewsbury and Atcham, which existed only between 1974 and 2009, and covered a much wider area than the town.

|

|

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Source: A Vision of Britain through Time | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

In 2011, the town of Shrewsbury had a population of 71,715. 93.9% of the population were classed as White British, compared with 95.4% for the surrounding district.[7]

Economy

Throughout the Medieval period, Shrewsbury was a centre for the wool trade,[82] and used its position on the River Severn to transport goods across England via the canal system. Unlike many other towns in this period, Shrewsbury never became a centre for heavy industry. By the early 1900s, the town became focused on transport services and the general service and professional sector, owing to its position on the A5 road, part of the strategic route to North Wales.[83] In 1958 the Sentinel Waggon Works at Shrewsbury was taken over by Rolls-Royce Limited for the manufacture of their range of diesel industrial engines, so that the factory at Derby could concentrate on aero engines. The factory which manufactured steam and later diesel locomotives had come on the market in 1956.[84]

The town is the location of the town and county councils, and a number of retail complexes, both in and out of the town centre, and these provide significant employment. Shrewsbury is well known for being home to a high number of independent businesses, including shops, cafes and restaurants. Wyle Cop in Shrewsbury is said to have the 'longest uninterrupted row of independent shops'.[85] Four in five jobs in the town are in the service industry. Within this sector, the largest employers are the administration and distribution sectors, which includes retail, food and accommodation.[81]

Shrewsbury is home to four shopping centres. The Darwin Shopping Centre houses many high street retailers such as Marks & Spencer, H&M, Topshop and Primark.[86] Riverside provides further retail accommodation for stores although all the major chains except Heron Foods (under Cooltrader branding) have moved out pending proposed closure of the centre for redevelopment.[87] A plan to redevelop Riverside and integrate a new development with the Darwin and Pride Hill centres was granted planning permission in April 2012. The project is dubbed "New Riverside".[88][89] The Parade Shopping Centre is a fourth centre exclusively housing independent retailers. There are two retail warehouse clusters: at Meole Brace Retail Park to the south, and at Sundorne Retail Park to the north. Major supermarkets in the town are the Tesco Extra at Harlescott, Morrisons on Whitchurch Road, Asda on Old Potts Way, and Sainsbury's at Meole Brace.

The visitor economy of Shrewsbury and Atcham was worth about £115 million in 2001, with about 2,500 people employed directly in the visitor industry and 3,400 indirectly. There were about 3.1 million visitors – both day visitors and staying visitors – to the borough in 2001, with 88% being day visitors and 12% being staying visitors; staying visitors accounted for 42% of spending.[90] Shrewsbury's position of being the only sizable town for a large area, especially to the west in Mid-Wales, allows it to attract a large retail base beyond that of its resident population. This is not only evident in the retail sector, but also in the healthcare sector, where the Royal Shrewsbury Hospital has the only A&E department westwards until Aberystwyth, about 75 miles (121 km) away.[91]

Businesses in Shrewsbury voted in favour of a Business Improvement District in late 2013 and Shrewsbury BID started operating in April 2014. Shrewsbury BID delivers on a five-year business plan of projects, which include major destination marketing campaigns, significant cost savings for businesses and strategic work ensuring the best possible town centre environment in which business can flourish. The company is governed by a board of directors and employs three staff full-time.[92]

Although a less prominent brewing centre than at Burton-on-Trent, beer made in Shrewsbury was celebrated as early as about 1400 when the bard Iolo Goch praised the supply of "Crwg Amwythig" dispensed at the Sycharth palace of Owain Glyndŵr.[93] In 1900 there were eight breweries in the town, chief among them being Southam's and Trouncer's, which also had their own maltings and owned many local public houses, as well as five other maltsters,[94] but the conventional brewing industry gradually closed after takeovers in the 1960s, and the last maltings, at Ditherington, in 1987.[95] A real ale brewery, The Salopian Brewery, was established in the town in 1995.[96] It was based in the Old Dairy on Mytton Oak Road before relocating in 2014 to Hadnall a few miles north of the town.[97]

In terms of social and economic deprivation, according to the Overall Index of Multiple Deprivation of 2004, one Super Output Area (SOA) in the town is in the bottom 15% of all areas nationally. This area is in the ward of Harlescott.[98] A further four SOAs fall into the bottom 30% nationally, these being in the wards of Monkmoor, Sundorne, Battlefield and Heathgates and Meole Brace. The most affluent areas of the town are generally to the south and west, around the grounds of Shrewsbury School, and the Copthorne area.

Architecture

Landmarks

The historic town centre still retains its medieval street pattern and many narrow passages. Some of the passages, especially those that pass through buildings from one street to the next, are called "shuts" (the word deriving from "to shoot through" from one street to another).[99] Many specialist shops, traditional pubs and local restaurants can be found in the hidden corners, squares and lanes of Shrewsbury. Many of the street names have remained unchanged for centuries and there are some more unusual names, such as Longden Coleham, Dogpole, Mardol, Frankwell, Roushill, Grope Lane, Gullet Passage, Murivance, the Dana, Portobello, Bear Steps, Shoplatch and Bellstone.[100]

The public library, in the pre-1882 Shrewsbury School building,[101] is on Castle Street. Above the main entrance are two statues bearing the Greek inscriptions "Philomathes" and "Polymathes". These portray the virtues "Lover of learning" and "Much learning" to convey the lesson that it is good to gain knowledge through a love of learning.

In the centre of the town lies The Quarry. This 29 acre (120,000 m2)[102] riverside park attracts thousands of people throughout the year and is enjoyed as a place of recreation. Shrewsbury has traditionally been known as the "Town of Flowers", a moniker incorporated into many of the signs on entrance to the town via major roads, although this was replaced in 2007 with 'the birthplace of Charles Darwin'.[10]

The British Army's Light Infantry has been associated with Shrewsbury since the 17th century when the first regiments were formed and many more regiments have been raised at Shrewsbury before being deployed all over the world from the American Revolutionary War to the current conflicts in Iraq and Afghanistan. Today, after several major reorganisations, the Light Infantry now forms part of the regiment known simply as the Rifles. Shrewsbury's Copthorne Barracks, spiritual home of the Light Division, ultimately housed the Headquarters of the British Army's 143 (West Midlands) Brigade before it moved in 2014, while that of the 5th Division disbanded in April 2012 as part of the reorganisation of the Army's Support Command.[103]

Between 1962 and 1992 there was a hardened nuclear bunker, built for No 16 Group Royal Observer Corps Shrewsbury, who provided the field force of the United Kingdom Warning and Monitoring Organisation and would have sounded the four-minute warning alarm in the event of war and warned the population of Shrewsbury in the event of approaching radioactive fallout.[104] The building was manned by up to 120 volunteers who trained on a weekly basis and wore a Royal Air Force style uniform. After the breakup of the communist bloc in 1989, the Royal Observer Corps was disbanded between September 1991 and December 1995. However, the nuclear bunker still stands just inside Holywell Street near the Abbey as a lasting reminder of the Cold War, but is now converted and used as a veterinary practice.

The tourist information centre is situated in the Shrewsbury Museum & Art Gallery in what used to be the old Music Hall theatre in The Square. The three main museums are Shrewsbury Museum & Art Gallery, Shrewsbury Castle (which houses the Shropshire Regimental Museum) and the Coleham Pumping Station.[105] There are various private galleries and art shops around the town, including the Gateway Education and Arts Centre.[106] Another notable feature of the town is Lord Hill's Column, the largest free-standing Doric column in the world.[107]

The Quantum Leap is an abstract sculpture unveiled in the town centre in 2009 to mark the bicentenary of the birth of Shrewsbury biologist Charles Darwin.

Bridges

Shrewsbury's town centre, being almost entirely encircled by the River Severn, has nine bridges across the river and many that cross the Rea Brook.

Working downstream from Frankwell Bridge, a modern pedestrian footbridge spans the River Severn between Frankwell and the town centre. Welsh Bridge was built in the 1790s to replace the ancient St George's Bridge. Further along from the Welsh Bridge is the Porthill Bridge, a pedestrian suspension bridge running between The Quarry and Porthill, built in 1922. The next bridge along the river is Kingsland Bridge, a privately owned toll bridge, and the subsequent bridge is the Greyfriars Bridge, a pedestrian bridge between Coleham and the town centre. Following the Greyfriars Bridge is the English Bridge, historically called Stone Bridge, which was rebuilt in the 1920s. Beyond it is the railway station, which is partly built over the river. After the station is Castle Walk Footbridge, another modern pedestrian footbridge.[108][109] The last bridge to cross the river within the Shrewsbury bypass area is called Telford Way, which has separate lanes for vehicles (A5112), bicycles and pedestrians. A. E. Housman wrote of the area this verse, which mentions the bridges of the town:[110]

High the vanes of Shrewsbury gleam

Islanded in Severn stream;

The bridges from the steepled crest,

Cross the water east and west.

Religious sites

There are many churches in Shrewsbury, including Shrewsbury Abbey, founded by Roger de Montgomery in 1083.[111] Shrewsbury Greek Orthodox Church, a former Anglican church building, is off Sutton Road to the south.[112] Shrewsbury is home to the Roman Catholic Shrewsbury Cathedral, by the Town Walls,[113] as well as two other parishes in Harlescott and Monkmoor, within the Roman Catholic Diocese of Shrewsbury. One of the houses in Fish Street, facing St Alkmund's Church, was the site of John Wesley's first preaching in Shrewsbury; a wall plaque records the date as 16 March 1761. According to legend, the spire of St Alkmund's Church was damaged by the Devil in 1553, and climbed four times by a drunken steeplejack in 1621.[114]

There are several Anglican churches in Shrewsbury.[115] Methodists,[116] Baptists[117] and the United Reformed Church are also represented, alongside newer church groups including Elim Pentecostal[118] and two Newfrontiers, which are:

- Barnabas Community Church Shrewsbury, in Longden Coleham and the town's largest Church.

- Hope Church Shrewsbury, in the north of the town.

[119][120] Shrewsbury Evangelical Church met in the former Anglican parish church of St Julian at the Wyle Cop end of Fish Street,[121] later moving into the Springfield estate in the eastern suburbs.[122] Shrewsbury's first non-Christian place of worship, a Muslim centre, was approved in 2013.[123]

Many community projects in Shrewsbury are based in, or have been started by local churches, including the Isaiah 58 project, which is the primary work amongst homeless people in the town, whilst 'Churches Together in Shrewsbury' works to help homeless people through the Ark project.[124][125] Shrewsbury Food Bank, based at Barnabas Community Church Centre and part of 'Food Bank PLUS,' provides debt relief for local people, as well as a wide range of social action initiatives including 'Money Advice' (a confidential, not for profit debt, benefits and financial help service) and Eclipse Child Bereavement, which works with local schools to help children who have experienced losses to overcome their situation. Also run by Barnabas are projects including '360 Journey to Work,' which help people gain skills in applying for jobs and basics like CV writing, and 'Cage football,' an initiative that is lent out to local community groups, youth clubs and other churches.[126]

Notable Salopians

There have been a number of notable Salopians, and people otherwise associated with the town of Shrewsbury, including Charles Darwin, the biologist and evolutionary theorist.[127] Darwin, one of the most important thinkers of the 19th century,[128] was born in Shrewsbury on 12 February 1809 at the Mount House, baptised at St Chad's Church and educated at Shrewsbury School. He spent his formative years in the town, the town's river and proximity to the countryside inspired his interest in the natural world and the abundance of ice-age boulders within the town sparked his interest in geology.[129] When he was a teenager, he worked with his father at the Royal Salop Infirmary. After leaving the town, Darwin frequently returned and stayed at the Lion Hotel on Wyle Cop.

Shrewsbury has been home to many contributors to literature. Thomas Churchyard (ca.1523–1604) son of a farmer, was an author of autobiographical or semi-autobiographical verse collections.[130] Before the First World War, the poet Wilfred Owen lived in the town, and there is a memorial to Owen at Shrewsbury Abbey.[131] Classicist Mary Beard was educated in Shrewsbury and her father was a prominent Shrewsbury architect.[132] In the early years of the 18th century, the Irish dramatist George Farquhar resided in the town while acting as a recruiting officer for the Army. He drew on this experience in writing the comedy The Recruiting Officer. The romantic novelist Mary Webb lived in and around Shrewsbury and was buried there upon her death. Other actors with associations with the town include Nick Hancock, presenter of They Think It's All Over, who, like Palin, was educated at Shrewsbury School.[133] Actor Jason Bateman's mother was born in Shrewsbury.[134] Comedian George Robey lived in the town, near Lord Hill's Column, before and during the Second World War.[135]

People with political associations have connections with the town. Leo Blair, the father of former Prime Minister Tony Blair, was a resident of the town.[136] Former residents have included Michael Heseltine, a Conservative politician who was educated at Shrewsbury School,[137] and Sir William Pulteney, 5th Baronet, who was once Britain's richest man, and was MP for Shrewsbury.[138] He lived in apartments at Shrewsbury Castle. Robert Clive was MP for Shrewsbury, and also the mayor.[139][140]

Ian Hunter (or Ian Patterson), the lead singer of the 1970s pop group Mott the Hoople, was a resident of 23a Swan Hill in the town centre, and wrote a song of the same name.[141] Lange, a DJ and dance music producer, who was born in Shrewsbury.[142] The 1980s pop group T'Pau was formed in the town and the band's vocalist Carol Decker was born and educated in the town, along with other members of the band.[143] Notable music historian and composer Charles Burney was born and educated in the town.[144]

Sporting Salopians include footballers Danny Guthrie of Newcastle United[145] and Shrewsbury Town youth academy graduates and England goalkeeper Joe Hart[146] and Wales midfielder David Edwards. Sheffield Wednesday and Scotland striker Steven Fletcher was born in the town, where his serviceman father was stationed. Four FA Cup Final winning players who took part in the first decade of the Cup's history were born in or lived in Shrewsbury: John Hawley Edwards, Henry Wace and John Wylie, of the Wanderers and Clopton Lloyd-Jones of Clapham Rovers.[147] Sandy Lyle, a professional golfer, was born in the town.[148] Neville Cardus spent some of his formative years as assistant cricket coach at Shrewsbury School.[149]

Other notable people of the town include; comic book artist Charlie Adlard was born in Shrewsbury and is most known for illustrating The Walking Dead; Robert Cadman, a performer and steeplejack, who is buried in the town, at St Mary's Church; Simon Gosling, a visual effects designer was born in the town, and was resident there until 1994;[150] John Gwynn, an 18th-century architect, who designed the English Bridge and the bridge at Atcham was born in the town;[151] Percy Thrower, the gardener and broadcaster lived in Shrewsbury, where he set up the garden centre near Meole Brace and just down the road from the football club.[152]

Flight Lieutenant Eric Lock DSO, DFC and Bar was born in nearby Bayston Hill and was educated at Prestfelde preparatory school on London Road. Lock became internationally recognised as a high scoring fighter ace of the Royal Air Force in the Second World War with 26 victories before his death in combat at the age of 21. He was the RAF's most successful British-born pilot in the Battle of Britain.[153][154] One Victoria Cross recipient is known to have lived in Shrewsbury; Arthur Herbert Procter, who was decorated in 1916 during World War I and retired from his later full-time clergy ministry in 1964 to briefly live at Mytton Oak Road, Copthorne, before relocating to Sheffield.[155]

The forerunner of Private Eye was a school magazine edited by Richard Ingrams, Willie Rushton, Christopher Booker and Paul Foot at Shrewsbury School in the mid-1950s.[156] Michael Palin, the writer, actor and comedian; John Peel, the tastemaker and radio DJ also attended Shrewsbury School.[157]

Culture

Museums and entertainment

Shrewsbury has a busy spring and summer events season, which includes music, art, food and sport.

The town is home to the 'longest running flower show in the world'. The annual Shrewsbury Flower Show is a two-day event, which takes place in mid-August, has been running for more than 125 years.[158] The event attracts around 100,000 visitors each year and offers a multitude of events, exhibitions and gardens, with a fireworks display at the end of each day.

The Shrewsbury Folk Festival has been held in Shrewsbury since 2006. Held annually over the August bank holiday, the event is very popular, with people travelling from across the UK to attend.[159]

Comics Salopia (formerly the Cartoon Festival) is a large biannual festival of the comics arts, attracting over a quarter of a million visitors. In format and scope it aims to rival on a smaller scale the world-famous Angouleme International Comics Festival in mid France.

Other events held in Shrewsbury's busy spring and summer of events include the Shrewsbury Bookfest, Shrewsbury Regatta, Cycle Grand Prix, Shrewsbury Carnival, Food Festival, Dragon Boat Race and the Coracle World Championships.[160] Since 2017, Shrewsbury International Comedy Festival has been held over the third weekend of July in multiple venues across town & featuring acts previewing material prior to the Edinburgh Fringe Festival.

Shrewsbury celebrates the intrinsic links to Darwin with an annual Darwin Festival in February. The two and a half week multi-media event celebrates the town as the 'Origin of Independent Thinking' with activities including lectures, dance performances and live music.[161]

The Old Market Hall cinema opened in 2004 in the prominent Tudor market hall positioned in The Square. The independent cinema features daily screens of films from around the world along with a cafe and bar.[162]

Theatre Severn is the town's main performing arts complex, it is situated in Frankwell next to the Welsh Bridge on the bank of the River Severn. The theatre includes two performance spaces, the 635 seat Main Auditorium and a smaller studio space, the Walker Theatre which can accommodate 250 seating or 500 standing. The venue includes a full sized dance studio, function rooms and a restaurant.[163] The new complex replaced the old theatre, the Music Hall, which itself has been refurbished and expanded in preparation for its current use as home to Shrewsbury Museum and Art Gallery (opened 2014).[164]

Further museums in the town include the acclaimed Shropshire Regimental Museum, renamed in 2019 Soldiers of Shropshire Museum,[165] based at Shrewsbury Castle,[9] and the restored 19th century steam-powered Coleham Pumping Station, which opens for tours on specific days each year. Nearby National Trust properties include the last remaining Town Walls Tower which dates from the 14th century and, just outside the town, Attingham Park, former home of the Noel-Hill family, Barons Berwick.[166]

There are some very old public houses, which have been continuously open, such as the Golden Cross in Princess Street, the Dun Cow in Abbey Foregate, and the King's Head in Mardol. The Golden Cross is reputed to be the oldest licensed public house in Shrewsbury and records show that it was used as an inn as far back as 1428. Its original name was the Sextry, because it was originally the sacristy of Old St Chad's Church.[167]

In the arts

Famous literary figures who have lived in or visited the town include (in the 17th century) Daniel Defoe, Celia Fiennes, the Shrewsbury School-educated Arthur Mainwaring and Ambrose Philips and playwright George Farquhar whose 1706 play 'The Recruiting Officer' was set in the town.[168]

The town appears in the Brother Cadfael novels by Ellis Peters (pen name of Edith Pargeter). The novels take Shrewsbury Abbey for their setting, with Shrewsbury and other places in Shropshire portrayed regularly, and have made Medieval Shrewsbury familiar to a wide worldwide readership.[169]

Later, in the 18th and 19th centuries, the likes of John Wesley, Thomas de Quincey and Benjamin Disraeli the latter of which was MP for Shrewsbury 1841–47, would visit the town. Charles Dickens once visited to present a series of lectures at the Music Hall, staying at the Lion Hotel. However, in this period the town's most prolific literary figure and famous son was born – Charles Darwin.

Darwin was educated at Shrewsbury School and later, with the development of his 1859 work On the Origin of Species became the pre-eminent naturalist of the 19th century. Although Darwin's work was both revolutionary and highly controversial at the time, his teachings and beliefs have become ever more globalised and he is today widely recognised as the father of the modern theory of evolution.

In his 1910 novel, Howards End, E. M. Forster makes a brief reference to "astonishing Shrewsbury", an impression he received after having visited the town in the early 20th century. In the same century, Shrewsbury became famous for its poets. The Great War poet Wilfred Owen was a resident. Mary Webb, the novelist, much loved the town and referred to it many a time in her works under the guise of Silverton.

In film, Shrewsbury was used as the setting for the popular 1984 film, A Christmas Carol,[170] which filmed many of its interior and exterior shots in and around the town. The gravestone prop of Ebenezer Scrooge (played by George C. Scott) that was used in the movie is still present in the graveyard of St Chad's Church.

In early 2017, Shrewsbury BID, The Hive and GRAIN Photography Hub organised an outdoor Magnum Photos exhibition.[171] Inspired by Shrewsbury's links to Charles Darwin, this exhibition showcased the theme of evolution through the eyes of international photographers. The 10-week exhibition was free to the public and staged at St Mary's Churchyard and The Square.

Media

Two newspapers are published for Shrewsbury – the local edition of the county's Shropshire Star and the more traditional Shrewsbury Chronicle, which is one of the oldest weekly newspapers in the country, having produced its first edition in 1772.[172][173] There are three radio stations that specifically serve either the Shrewsbury area or encompass it as part of a Shropshire-wide broadcast. They are: Free Radio Shropshire & Black Country;,[174] BBC Radio Shropshire, which is based in Shrewsbury;[175] and, as of September 2006, The Severn, which broadcasts from the Shropshire Star building in Telford.[176]

In 2009 an online independent media company launched covering Shrewsbury and Shropshire. shropshirelive.com,[177]

Food

Shrewsbury is well known in culinary circles for being the namesake of a classic English dessert.[178] Shrewsbury cakes (or biscuits) are typically crisp and brittle creations that may incorporate fruit. They can be small in size for serving several at a time, or large for serving as a dessert in their own right. Traditionally Shrewsbury cakes have a distinct hint of lemon.

The playwright William Congreve mentioned Shrewsbury cakes in his play The Way of the World in 1700 as a simile[179] (Witwoud – "Why, brother Wilfull of Salop, you may be as short as a Shrewsbury cake, if you please. But I tell you 'tis not modish to know relations in town"). The recipe is also included in several early cookbooks including The Compleat Cook of 1658.[180] A final reference to the cakes can be seen to this day as the subject of a plaque affixed to a building close to Shrewsbury's town library by the junction of Castle Street and School Gardens. The aforementioned plaque marks the spot where the Shrewsbury Cake's recipe is said to have been pioneered in 1760 by Mr Pailin; a further quote, drawn from Richard Harris Barham's Ingoldby Legends, reads:

Oh! Pailin. Prince of Cake Compounders

The mouth liquifies at the very name.

Shrewsbury is the origin of the most popular Simnel cake recipe. Different towns had their own recipes and shapes of the Simnel cake. Bury, Devizes and Shrewsbury produced large numbers to their own recipes, but it is the Shrewsbury version that became most well known. Shrewsbury had a large cheese market in Victorian times.

Education

Shrewsbury is home to Shrewsbury School, a public school, on a large site (in Kingsland) just south of the town centre overlooking the loop of the Severn. The school was once in the town centre, in the buildings that are now the main county library on Castle Street.[181] Opposite it on the other side of the river is Shrewsbury High School, an independent girls' day school.

The long established Prestfelde School is an independent preparatory school, on London Road, close to the Lord Hill's Column. As part of the Woodard Schools group, it is affiliated to the largest group of Church of England schools in the country. Whilst originally a school for boys it diversified and, in the late 1990s, started accepting girls between the ages of three and thirteen. The school is set in 30 acres (12 ha) of grounds on the outskirts of the town.[182] The town's other long-established boys' preparatory school, Kingsland Grange (on Old Roman Road in Kingsland, Shropshire|Kingsland), merged in 2007 with the junior department of Shrewsbury Girls' High School, sharing the two sites with some classes remaining all-boys or all-girls, but others switching to a co-ed format.[183]

Adcote School is an independent day and boarding school for girls, 5 miles (8.0 km) northwest of Shrewsbury. The school was founded in 1907 and is set in a Grade I listed country house built in 1879 for Rebecca Darby – a great niece of Abraham Darby and a member of the iron-master family who built Ironbridge.

However, the majority of the town's pupils attend one of the seven comprehensive schools. The Priory School, formerly a grammar school for girls;[184] Meole Brace School currently carries the status of Science College; The Grange School the status of Arts College; Sundorne School the status of Sports College and Belvidere School has the status of Technology College.

In 2016, The Grange and Sundorne officially merged to form Shrewsbury Academy. The school has two campuses however it is planned in the next few years for all pupils to move to the Corndon Crescent site, formerly Sundorne. In the future, a new building will be constructed in Shrewsbury to house Shrewsbury Academy.

The Wakeman School, which was geographically the closest school to the town centre 'loop', next to the English Bridge, was previously called Shrewsbury Technical School, and was attended by the notable First World War poet Wilfred Owen. It closed as part of reorganisation in July 2013.[185] Additionally, two other establishments outside town serve town students – The Corbet School to the north-west at Baschurch; and Mary Webb School, in the village of Pontesbury to the south-west.

Post-16 education is handled by Shrewsbury Sixth Form College, previously the Priory School for Boys,[186] ranked 17th in the top 20 of sixth form colleges nationally by the Sunday Times newspaper in November 2012,[187] and Shrewsbury College of Arts and Technology, which handles primarily vocational courses.

During the Commonwealth which followed the execution of Charles I, a Shropshire man, Richard Baxter, a puritan minister suggested the establishment of a university for Wales at Shrewsbury and thought he could obtain the support of Cromwell and Parliament for the scheme.[188] In the end the scheme came to nothing and it was not until the 2000s that higher education institutions were established in the town: University Centre Shrewsbury has been offering postgraduate courses since autumn 2014 and undergraduate students are being welcomed to the institution from autumn 2015. Established by the University of Chester and Shropshire Council, the University Centre is focused on high-quality teaching and research, fostering entrepreneurship, contributing to the community and, ultimately, making a global impact.[189]

Transport

Shrewsbury is the county's public transport hub; it has road and rail links to the rest of the county and country.

Lines

Five railway lines connect the town to most corners of Shropshire and the region. Shrewsbury railway station is served by Transport for Wales Rail and West Midlands Trains with trains running north to Chester, Manchester Piccadilly, Crewe and Wrexham General, south to Hereford and Cardiff Central, west to Aberystwyth, and east to Birmingham International via Telford, Shifnal and Wolverhampton.[191] Heart of Wales line trains also operate to Swansea.

Services

In May 1998, Virgin Trains West Coast introduced a service from Shrewsbury to London Euston;[192] it was withdrawn in 2000. On 28 April 2008, open access operator Wrexham & Shropshire commenced services from Wrexham General to London Marylebone, restoring the county's direct rail link to the capital; previously, Shropshire had been one of only two mainland English counties without a dedicated service to the capital, the other being Rutland.[193] However, the service ceased on 28 January 2011. Virgin Trains reintroduced a service to London Euston in December 2014.[194]

Shrewsbury General

The main railway station building of Shrewsbury General includes a clock tower, imitation Tudor chimneys and carved heads in the frames of every window. There is a small British Transport Police station within the building.

Closed stations

- Shrewsbury Abbey

- Shrewsbury West

Proposed station

- Shrewsbury Parkway

Bus

Bus services in the town are operated by Arriva Midlands and serve most parts of the town from Shrewsbury bus station, adjacent to the Darwin Shopping Centre, and a short walk from the railway station. Arriva also operate county services both independent of and on behalf of Shropshire County Council. There are other bus companies operating around the Shrewsbury area, including Boulton's of Shropshire, Minsterley Motors and Tanat Valley Coaches with the last operating services crossing from over the Welsh border from nearby towns including Llanfyllin, Montgomery, Newtown and Welshpool.

Shrewsbury has a park & ride bus scheme in operation and three car parks on the edge of town are used by many who want to travel into the town centre. The three car parks are at Harlescott (to the north, colour-coded blue), Oxon (to the west, colour-coded pink) and Meole Brace (to the south, colour-coded green). It is proposed that a fourth one be built to the east of the town, at either Emstrey or Preston.[195]

Road

Shrewsbury has been an important centre for road traffic. In 1815, Thomas Telford designed a new coaching route from London to Holyhead in order to improve communications with Ireland. He routed the new road via Shrewsbury, which opened in 1830. The road is now the A5.[196] The road connects the town northwest to Oswestry, and east towards Telford, where it joins the M54. The A5 once ran through the town centre, until a bypass was built in the 1930s. Subsequently, in 1992, a 17-mile (27 km) dual carriageway was completed at a cost of £79 million to the south of the town and was made to form part of the A5 route. This dual carriageway was built further out of the town to act as a substantial link to Telford, as well as a bypass for the town.[197]

The A49 also goes to Shrewsbury, joining the A5 at the south of the town, coming from Ludlow and Leominster. At this point, the road merges with the A5 for 3 miles (4.8 km), before separating again to the east of the town. From there it runs north, passing Sundorne, then Battlefield, before heading out towards Whitchurch. At Battlefield, the A53 route begins and heads north-east towards Shawbury and Market Drayton, then onwards towards Newcastle-under-Lyme and Stoke-on-Trent.

The A458 (Welshpool-Bridgnorth) runs through the town centre, entering in the west and leaving to the southeast. The A528 begins in the town centre and heads north, heading for Ellesmere. The A488 begins just west of the town centre in Frankwell and heads out to Bishop's Castle, Clun and Knighton crossing the border in the southwest of Shropshire.

Major roads within the town include the A5112, A5191 and A5064. The A5191 goes north-south via the town centre, while the A5112 runs north-south to the east of the town centre. The A5064 is a short, one mile (1.6 km) stretch of road to the southeast of the town centre, called "London Road". Additionally, the A5124, the most recent bypass, was completed in 1998, and runs across the northern edge of the town at Battlefield (connecting the A49/A53 to the A528), though it did exist before as Harlescott Lane (which has since become unclassified).

Construction of a major new artery referred to as the North West Relief Road (NWRR) was granted central government funding in April 2019. Together with the existing A5 and A49 by-passes, the Battlefield Link Road (A5124) and the Oxon Link Road (construction expected to be completed by 2021), this will result in the completion of the ring road around the outskirts of the town. The NWRR will involve the construction of a new bridge over the River Severn, upstream from the town centre.[198]

Cycling

Shrewsbury has a comprehensive network of on-road and traffic-free cycle routes.[199] In 2008 the town was awarded Cycling Town status by Cycling England;[200] as a result, it benefited from £1.8 million of grant funding from the Department for Transport between 2008 and 2011. The funding was used to make improvements to the cycle network in Shrewsbury, and to provide cycle training, information and advice to people to help encourage them to cycle to school and work.[201]

Sport

.jpg.webp)

Shrewsbury is home to a professional football club, Shrewsbury Town Football Club. The team currently competes in the third tier of English football, Football League One and since 2007 has played their home games at New Meadow – from 1910 to 2007 the club played at the Gay Meadow stadium. Shrewsbury Town's achievements include winning the Welsh Cup six times, a record for an English club, a 10-year run in the old Second Division now known as The Championship from 1979 until 1989, a Third Division Championship in 1979, a Division 3 Championship and victory in the Conference National Playoff Final 2004. The town is also home to a semi-professional football club, Haughmond, who take their name from the nearby Haughmond Hill. The team currently compete in the Midland Football League and play their home games at Shrewsbury Sports Village, in the Sundorne area of the town.

There is a local rugby club, Shrewsbury Rugby Club.[202]

The River Severn in the town is used for rowing by both Pengwern Boat Club[203] and the Royal Shrewsbury School Boat Club (RSSBC).[204] More recently these have been joined by rowing students of Harper Adams University, University Centre Shrewsbury and some crews from other local schools. There in an annual rowing regatta in the town in May.

Shrewsbury Sports Village is a sports centre in the Sundorne district of the town, aimed at providing a wide range of sports facilities for townspeople.[205] There are a number of motorsports and golf facilities (including Meole Brace Municipal Golf Course) in the area. The local motorsports heritage includes the Loton Park Hillclimb and Hawkstone Park Motocross Circuit near Shrewsbury. Shrewsbury Motocross Club has staged motocross events in the area for over 30 years.[206]

Shrewsbury holds its own annual Sprint Triathlon which takes place each September at the West Midlands Country Showground and organised by SYTri (Shrewsbury Triathlon Club) and permitted by the British Triathlon Federation.

A free weekly parkrun takes place in the centre of Shrewsbury. Shrewsbury has also seen activity in the physical discipline, Parkour.[207]

Twin town

Shrewsbury has no twin towns. Until 2018 Shrewsbury was twinned with Zutphen, Netherlands, a move inspired by the fact Sir Philip Sidney, an alumnus of Shrewsbury School, was fatally wounded there in 1586. At the end of the Second World War Shrewsbury's then Mayor, Harry Steward, who was made in 1946 an honorary citizen of Zutphen in return, launched an appeal for second-hand tools, clothes, bedding and other materials towards the town's post-war reconstruction after Nazi German occupation and war damage.[208] The association was ended in late 2018 when the municipal council of Zutphen chose to review all of its global twinning arrangements due to budgetary constraints.[209]

A potential twinning of Shrewsbury with Bayreuth, Germany, was under discussion in 2009.[210]

See also

- List of Mayors of Shrewsbury

- Listed buildings in Shrewsbury

- Reabrook Valley – local nature reserve

- Shrewsbury sauce

Notes

- RAF Shawbury is located approximately 7 miles (11 km) NE of Shrewsbury, and 12 miles (19 km) NW of Telford.

References

- Shrewsbury Town Council Archived 20 April 2017 at the Wayback Machine Contact Us (accessed 23 March 2017)

- Shrewsbury Town Council

- National Statistics Archived 7 April 2014 at the Wayback Machine – population density and area of the parish of Shrewsbury in 2011

- "'Shroosbury' v 'Shrowsbury'". Shropshire Star. Shrewsbury: MNA Media. 6 February 2008. p. 1. Archived from the original on 15 March 2015. Retrieved 6 March 2013.

- Room, Adrian (2006). Placenames of the World: Origins And Meanings of the Names for 6,600 Countries, Cities, Territories, Natural Features And Historic Sites. Stamford: McFarland. p. 345. ISBN 0786422483.

- Oxford Dictionary of English (Second edition (revised) ed.). 647563 of 801946: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-861057-2.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location (link) - "Local statistics". Office for National Statistics. 12 May 2017. Archived from the original on 25 November 2016. Retrieved 25 July 2017.

- "About Shrewsbury | Original Shrewsbury". Enjoy England. Archived from the original on 1 November 2007. Retrieved 14 June 2018.

- "Shrewsbury Castle and Shropshire Regimental Museum | Original Shrewsbury". originalshrewsbury.co.uk. Retrieved 14 June 2018.

- "Charles Darwin: His Life, Work and Shrewsbury | Original Shrewsbury". originalshrewsbury.co.uk. Archived from the original on 14 June 2018. Retrieved 14 June 2018.

- Jenkins, Simon (2008). Wales: Churches, Houses, Castles. London: Allen Lane. p. 245.

- "Imperial Gazetteer entry for Shrewsbury". Visions of Britain. Archived from the original on 22 October 2012. Retrieved 4 March 2008.

- "Shrewsbury". Encarta. Microsoft. Archived from the original on 18 July 2008. Retrieved 24 February 2008.

- "About Shrewsbury | Original Shrewsbury". originalshrewsbury.co.uk. Retrieved 14 June 2018.

- Shipley, John (2019). Secret Shrewsbury. Amberley Publishing. ISBN 978-1445678450.

- "The Wroxeter Hinterland Project". University of Birmingham. Archived from the original on 25 September 2006. Retrieved 23 February 2008.

- Pett, Daniel (7 September 2009). "Recent discovery of a Roman Coin Hoard in the Shrewsbury Area". Portable Antiquities Scheme. Archived from the original on 6 March 2012. Retrieved 9 July 2010.

- Reavill, Peter (25 October 2011). "Inquest into largest coin hoard from Shropshire". Portable Antiquities Scheme. Retrieved 12 February 2017.

- "Shrewsbury Historic Timeline | Original Shrewsbury". Archived from the original on 29 July 2017.

- Lambert, Tim. "Saxon and Medieval Shrewsbury". A Short History of Shrewsbury, Shropshire, England. A World History Encyclopaedia. Archived from the original on 15 March 2012.

- "Shrewsbury Abbey | Original Shrewsbury". originalshrewsbury.co.uk. Retrieved 14 June 2018.

- "Shrewsbury Castle". Castle Wales. Retrieved 8 June 2018.

- "Hospitals: Shrewsbury Pages 105-108 A History of the County of Shropshire: Volume 2. Originally published by Victoria County History, London, 1973". British History Online. Retrieved 13 July 2020.

- "Acton Burnell Castle". Virtual Shropshire. Archived from the original on 30 November 2007. Retrieved 28 November 2007.

- Pierce, Thomas Jones (1959). "Dafydd ap Gruffydd (David III, died 1283), prince of Gwynedd". Dictionary of Welsh Biography. National Library of Wales.

- Mitchell, Jean (March 1955). "Reviewed Work: The Shrewsbury Drapers and the Welsh Wool Trade in the XVI and XVII Centuries. by T. C. Mendenhall". Review. The Economic Journal. Wiley. 65 (257): 147–149. doi:10.2307/2227468. JSTOR 2227468.

- History of Shrewsbury Drapers, Shrewsbury Drapers, archived from the original on 25 March 2016, retrieved 2 April 2016

- Shipley, John (2017). The A-Z of Curious Shropshire : Strange Stories of Mysteries, Crimes and Eccentrics. The History Press. ISBN 9780750983174.

The Black Death arrives in Shropshire around the spring of 1349....

- Gasquet, Francis A. (1908). The Black Death of 1348 and 1349 (2nd ed.). London: George Bell & Sons. pp. 166–167. ISBN 9781331933663.

- "Battle of Shrewsbury – Henry VI at Shrewsbury". About.com. Archived from the original on 4 May 2008. Retrieved 23 February 2008.

- "Henry IV, Part 1, Act 5, scene 2". Folger Shakespeare. Retrieved 14 July 2020.

- Carlton 1994, p. 262.

- "Shrewsbury, the house at the Castle Gates and the hanged Irish mercenaries". Gwendda. 29 January 2015. Archived from the original on 25 November 2016.

- Lewis, Samuel (1833). A Topographical Dictionary of England: With Historical and Statistical Descriptions. S. Lewis & Co.

- Pidgeon, Henry (1837). Memorials of Shrewsbury: being a concise description of the town and its environs. p. 116.

Old Shire Hall Shrewsbury Robert Smirke 1837.

- "Former Mayors of Shrewsbury 1638 to present". Shrewsbury Town Council. Archived from the original on 29 November 2014. Retrieved 19 November 2014.

- "Kings Shropshire Light Infantry". Durham Light Infantry Association, South Shields. 7 January 2013. Archived from the original on 8 May 2012.

- W. G. Rimmer, 'Castle Foregate Flax Mill, Shrewsbury' Transactions of Shropshire Archaeological Society LVI (1957–60), 49ff.

- "'Father of the skyscraper' rescued for the nation". English Heritage. Archived from the original on 16 January 2009.

- "Thomas Telford in Shropshire". BBC Shropshire. Archived from the original on 31 May 2009. Retrieved 4 March 2008.

- "History of Charles Darwin" (PDF). Ondix.com. Archived (PDF) from the original on 17 December 2008. Retrieved 23 February 2008.

- Simcox, Kenneth (1983). A Town at War, Shrewsbury 1939–45. Shropshire Libraries. p. 14. ISBN 0-903802-25-2.

- Rowley, Trevor (2006). The English Landscape in the Twentieth Century. A&C Black. p. 149. ISBN 9781852853884. Retrieved 13 April 2008.

shrewsbury england redevelopment architecture 1960s 1970s.

- "Smithfield Cattle Market, Shrewsbury". Discovering Shropshire's History. Retrieved 14 July 2020.

- Kirby, Terry (26 August 1992). "Firebomb attack at army museum linked to IRA". The Independent.

- "Shropshire bombing". Shropshire History. Retrieved 19 June 2019.

- "Shrewsbury flood alleviation scheme". Environment Agency. Archived from the original on 10 January 2007. Retrieved 24 February 2008.

- "Flood watch continues on Severn". BBC Shropshire News. 10 December 2007. Archived from the original on 13 December 2007. Retrieved 24 February 2008.

- "Advantage WM". Archived from the original on 21 June 2008. Retrieved 18 September 2007.

- "Travel – A day on the Shrewsbury-Birmingham line". BBC Shropshire. Archived from the original on 27 January 2007. Retrieved 13 April 2008.

- "Jail most overcrowded in country". BBC News. 27 July 2005. Retrieved 16 January 2008.

- Shropshire Star Archived 1 February 2015 at the Wayback Machine Sold: Shrewsbury's Dana prison to become homes and offices (20 November 2014)

- "Case study on the experience of newly established local (parish and town) councils". National Association of Local Councils. Retrieved 14 July 2020.

- "Haughmond Hill". Shropshire Geology. Archived from the original on 9 October 2007. Retrieved 2 January 2008.

- "Shropshire's Geological Trail". Shropshire Rocks!. Archived from the original on 19 November 2008. Retrieved 2 January 2008.

- "Bayston Hill Parish Council". Shrop.net. Archived from the original on 27 July 2007. Retrieved 16 March 2008.

- "Expansion of Retail parks". Shrewsbury & Atcham council. Retrieved 16 March 2008.

- "Shropshire". MSN Encarta. Archived from the original on 18 July 2008. Retrieved 24 February 2008.

- "1971-00 average warmest day". Archived from the original on 11 June 2012. Retrieved 3 March 2011.

- "1971-00 >25c days average". Archived from the original on 11 June 2012. Retrieved 3 March 2011.

- "1990 Maximum". Archived from the original on 11 June 2012. Retrieved 3 March 2011.

- "1971-00 average coldest day". Archived from the original on 11 June 2012. Retrieved 3 March 2011.

- "1981 December". Archived from the original on 19 January 2011. Retrieved 3 March 2011.

- "Shawbury 1991–2020 averages". Met Office. Retrieved 21 July 2022.

- "Indices Data – Shawbury STAID 1633". KNMI. Retrieved 21 July 2022.

- "Monthly weather forecast and Climate – Shawbury, United Kingdom". Weather Atlas. Retrieved 21 July 2022.

- "About The Column". Friends of Lord Hill's Column. Retrieved 15 February 2022.

- "Establishment of Shrewsbury Town Council". Shrewsbury and Atcham Borough Council. Retrieved 4 April 2008.

- "Shropshire County Council Home Page". Shropshire County Council. Archived from the original on 11 May 2008. Retrieved 23 February 2008.

- "Benjamin Disraeli (1804–1881)". VictorianWeb.org. Archived from the original on 14 February 2008. Retrieved 23 February 2008.

- "Culture and Arts – Zutphen on the Ijsel". BBC Shropshire. Archived from the original on 15 December 2004. Retrieved 18 September 2007.

- "The Herefordshire Light Infantry". British Light Infantry Regiments. LightInfantry.org.uk. 18 September 2016.

- The Macmillan Guide to the United Kingdom 1978-79. Palgrave Macmillan. 1978. ISBN 978-1349815111.

- "The Mayor of Shrewsbury | Shrewsbury Town Council". www.shrewsburytowncouncil.gov.uk. Retrieved 14 June 2018.

- "Contact us | Shrewsbury Town Council". www.shrewsburytowncouncil.gov.uk. Retrieved 14 June 2018.

- "Riggs Hall Riggs Hall, to rear of Library". Historic England. Archived from the original on 24 March 2017. Retrieved 25 July 2017.

- "Origins of the name of Shrewsbury". Shrewsbury and Atcham Borough Council. Archived from the original on 27 September 2007. Retrieved 17 January 2008.

- "Shrewsbury and Atcham Borough Council". civicheraldry.co.uk. Archived from the original on 20 November 2007. Retrieved 5 April 2008.

- "Census – 2001 – Population & Age Structure". Shropshire County Council. Archived from the original on 30 June 2006. Retrieved 2 January 2008.

- "Shrewsbury". World Gazetteer. Archived from the original on 1 October 2007. Retrieved 16 January 2008.

- "Shrewsbury Town" (PDF). Safety Partnership. Archived from the original (PDF) on 17 December 2008. Retrieved 17 January 2008.

- "The Shrewsbury Drapers Guild". shrewsburydrapers.org.uk. Archived from the original on 20 November 2008. Retrieved 4 April 2008.

- "Shrewsbury, Shropshire Industry Statistics". A Vision of Britain. Retrieved 9 March 2008.

- Robotham, William Arthur (1970). Silver Ghosts and Silver Dawn. London: Constable. pp. 160, 161.

- "Wyle Cop | Original Shrewsbury". originalshrewsbury.co.uk. Retrieved 14 June 2018.

- "Darwin and Pride Hill Shopping Centres | Original Shrewsbury". originalshrewsbury.co.uk. Retrieved 14 June 2018.

- "Shrewsbury Riverside development moves forward despite calls for a pause". Shropshire Star. 24 February 2022. Retrieved 19 October 2022.

- "£150m Shrewsbury mega mall approved", Construction Enquirer, 19 April 2012, archived from the original on 5 June 2012

- "Property Week, Shearer shapes Shrewsbury". Archived from the original on 29 March 2012. Retrieved 1 February 2011.

- "A Visitor Economy Strategy and Action Plan for Shrewsbury & Atcham". Shrewsbury & Atcham Borough Council. Archived from the original on 27 September 2006. Retrieved 21 March 2008.

- "Hospital's cash plans are delayed". BBC News. 10 July 2006. Archived from the original on 13 July 2006. Retrieved 23 February 2008.

- "Shrewsbury BID". Archived from the original on 9 May 2017.

- Pidgeon, Henry (1851). Memorials of Shrewsbury. J. H. Leake. p. 261.

- Kelly's Directory of Shropshire. Kelly's. 1900. pp. 333, 391.

- "Shrewsbury Flaxmill Maltings Story (see Creating a Master Plan for the future)". Friends of the Flaxmill-Maltings. Archived from the original on 22 December 2018. Retrieved 21 December 2018.

- "Salopian Brewing Company Ltd". www.quaffale.org.uk. Retrieved 9 December 2017.

- ":: Welcome to Salopian Breweries". Salopian Brewery. Archived from the original on 2 October 2017. Retrieved 9 December 2017.

- "Index of multiple deprivation – overall results". Shropshire County Council. Archived from the original on 21 November 2008. Retrieved 17 January 2008.

- Scott-Davies, Allan; Sears, R.S., Shuts and Passages of Shrewsbury, Shropshire Books, June 1986. ISBN 978-0-903802-34-5

- "Shropshire Information". FatBadgers.co.uk. Archived from the original on 2 February 2008. Retrieved 23 February 2008.

- "Shrewsbury School history". shrewsbury.org.uk. Archived from the original on 14 March 2009. Retrieved 11 May 2009.

- "The Quarry Park | Original Shrewsbury". originalshrewsbury.co.uk. Retrieved 14 June 2018.

- "The Kings Shropshire Light Infantry (53rd and 85th foot)". Army.mod.uk. Archived from the original on 28 July 2006. Retrieved 4 March 2008.

- "UKWMO Group Controls". Subbrit.org.uk. Archived from the original on 25 October 2007. Retrieved 17 March 2008.

- "Shrewsbury Museums". Shrewsbury Museum Service. Archived from the original on 3 May 2006. Retrieved 18 September 2007.

- "The Gateway | Original Shrewsbury". originalshrewsbury.co.uk. Retrieved 14 June 2018.

- "Photo Gallery". Shrewsbury and Atcham Borough Council. Archived from the original on 7 November 2007. Retrieved 2 January 2008.

- "A Short History of Shrewsbury". localhistories.org. Archived from the original on 19 February 2008. Retrieved 3 February 2008.

- "Severn Bridges | Original Shrewsbury". originalshrewsbury.co.uk. Archived from the original on 14 June 2018. Retrieved 14 June 2018.

- "Complete Housman". greenend.org.uk/~martinh. Archived from the original on 13 January 2008. Retrieved 17 March 2008.

- "History of Shrewsbury Abbey". ShrewsburyAbbey.com. Archived from the original on 21 June 2008. Retrieved 17 March 2008.

- "Shrewsbury Orthodox Church". ShrewsburyOrthodox.com. Archived from the original on 11 May 2008. Retrieved 17 March 2008.

- "Shrewsbury Cathedral Home Page". ShrewsburyCathedral.org. Archived from the original on 5 June 2008. Retrieved 17 March 2008.