Solar panel

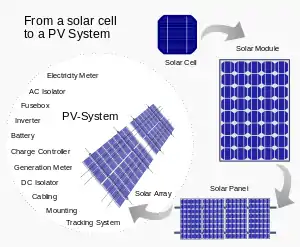

A solar cell panel, solar electric panel, photo-voltaic (PV) module or solar panel is an assembly of photovoltaic cells mounted in a framework for generating energy. Solar panels use sunlight as a source of energy to generate direct current electricity. A collection of PV modules is called a PV panel, and a system of PV panels is called an array. Arrays of a photovoltaic system supply solar electricity to electrical equipment.

History

In 1839, the ability of some materials to create an electrical charge from light exposure was first observed by the French physicist Edmond Becquerel.[1] Though these initial solar panels were too inefficient for even simple electric devices, they were used as an instrument to measure light.[2]

The observation by Becquerel was not replicated again until 1873, when the English electrical engineer Willoughby Smith discovered that the charge could be caused by light hitting selenium. After this discovery, William Grylls Adams and Richard Evans Day published "The action of light on selenium" in 1876, describing the experiment they used to replicate Smith's results.[1][3]

In 1881, the American inventor Charles Fritts created the first commercial solar panel, which was reported by Fritts as "continuous, constant and of considerable force not only by exposure to sunlight but also to dim, diffused daylight."[4] However, these solar panels were very inefficient, especially compared to coal-fired power plants.

In 1939, Russell Ohl created the solar cell design that is used in many modern solar panels. He patented his design in 1941.[5] In 1954, this design was first used by Bell Labs to create the first commercially viable silicon solar cell.[1]

Theory and construction

Photovoltaic modules use light energy (photons) from the Sun to generate electricity through the photovoltaic effect. Most modules use wafer-based crystalline silicon cells or thin-film cells. The structural (load carrying) member of a module can be either the top layer or the back layer. Cells must be protected from mechanical damage and moisture. Most modules are rigid, but semi-flexible ones based on thin-film cells are also available. The cells are usually connected electrically in series, one to another to the desired voltage, and then in parallel to increase current. The power (in watts) of the module is the mathematical product of the voltage (in volts) and the current (in amperes) of the module. The manufacturing specifications on solar panels are obtained under standard conditions, which is not the real operating condition the solar panels are exposed to on the installation site.[6]

A PV junction box is attached to the back of the solar panel and functions as its output interface. External connections for most photovoltaic modules use MC4 connectors to facilitate easy weatherproof connections to the rest of the system. A USB power interface can also be used.[7] Solar panels also use metal frames consisting of racking components, brackets, reflector shapes, and troughs to better support the panel structure.

Arrays of PV modules

A single solar module can produce only a limited amount of power; most installations contain multiple modules adding voltages or current to the wiring and PV system. A photovoltaic system typically includes an array of photovoltaic modules, an inverter, a battery pack for energy storage, charge controller, interconnection wiring, circuit breakers, fuses, disconnect switches, voltage meters, and optionally a solar tracking mechanism. Equipment is carefully selected to optimize output, and energy storage, reduce power loss during power transmission, and convert from direct current to alternating current.

Smart solar modules

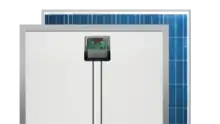

Several companies have begun embedding electronics into PV modules. This enables performing MPPT for each module individually, and the measurement of performance data for monitoring and fault detection at module level. Some of these solutions make use of power optimizers, a DC-to-DC converter technology developed to maximize the power harvest from solar photovoltaic systems. As of about 2010, such electronics can also compensate for shading effects, wherein a shadow falling across a section of a module causes the electrical output of one or more strings of cells in the module to fall to zero, but not having the output of the entire module fall to zero.

Smart modules are a type of solar panel that has a power optimizer embedded into the solar module at the time of manufacturing. Typically the power optimizer is embedded in the junction box of the solar module. Power optimizers attached to the frame of a solar module, or connected to the photovoltaic circuit through a connector, are not properly considered smart modules.[8]

Smart modules are different from traditional solar panels because the power electronics embedded in the module offers enhanced functionality such as panel-level maximum power point tracking, monitoring, and enhanced safety.

History

Solar panel installers saw significant growth between 2008 and 2013.[9] Due to that growth many installers had projects that were not "ideal" solar roof tops to work with and had to find solutions to shaded roofs and orientation difficulties.[10] This challenge was initially addressed by the re-popularization of micro-inverters and later the invention of power optimizers.

Solar panel manufacturers partnered with micro-inverter companies to create AC modules and power optimizer companies partnered with module manufacturers to create smart modules.[11] In 2013 many solar panel manufacturers announced and began shipping their smart module solutions.[12]

Module interconnection

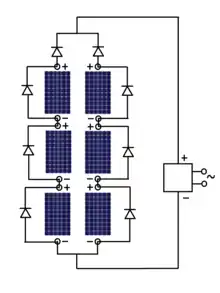

Module electrical connections are made with conducting wires that take the current off the modules and are sized according to the current rating and fault conditions.

Panels are typically connected in series of one or more panels to form strings to achieve a desired output voltage, and strings can be connected in parallel to provide the desired current capability (amperes) of the PV system.

Blocking and bypass diodes may be incorporated within the module or used externally, to deal with partial array shading, to maximize output. For series connections, bypass diodes are placed in parallel with modules to allow current to bypass shaded modules which would be high resistance. For paralleled connections, a blocking diode may be placed in series with each module's string to prevent shaded strings' internal impedance from short circuiting other strings.

Concentrator

Some special solar PV modules include concentrators in which light is focused by lenses or mirrors onto smaller cells. This enables the use of cells with a high cost per unit area (such as gallium arsenide) in a cost-effective way.

Mounting and tracking

.jpg.webp)

To maximize total energy output, modules are often oriented to face south (in the Northern Hemisphere) or north (in the Southern Hemisphere) and tilted to allow for the latitude.

Ground

Large utility-scale solar power plants usually use ground-mounted photovoltaic systems. Their solar modules are held in place by racks or frames that are attached to ground-based mounting supports.[13][14] Ground based mounting supports include:

- Pole mounts, which are driven directly into the ground or embedded in concrete.

- Foundation mounts, such as concrete slabs or poured footings

- Ballasted footing mounts, such as concrete or steel bases that use weight to secure the solar module system in position and do not require ground penetration. This type of mounting system is well suited for sites where excavation is not possible such as capped landfills and simplifies decommissioning or relocation of solar module systems.

Roof

Roof-mounted solar power systems consist of solar modules held in place by racks or frames attached to roof-based mounting supports.[15] Roof-based mounting supports include:

- Rail mounts, which are attached directly to the roof structure and may use additional rails for attaching the module racking or frames.

- Ballasted footing mounts, such as concrete or steel bases that use weight to secure the panel system in position and do not require through penetration. This mounting method allows for decommissioning or relocation of solar panel systems with no adverse effect on the roof structure.

- All wiring connecting adjacent solar modules to the energy harvesting equipment must be installed according to local electrical codes and should be run in a conduit appropriate for the climate conditions

Tracking

Solar trackers increase the energy produced per module at the cost of mechanical complexity and increased need for maintenance. They sense the direction of the Sun and tilt or rotate the modules as needed for maximum exposure to the light.[16][17]

Alternatively, fixed racks can hold modules stationary throughout the day at a given tilt (zenith angle) and facing a given direction (azimuth angle). Tilt angles equivalent to an installation's latitude are common. Some systems may also adjust the tilt angle based on the time of year.[18]

On the other hand, east- and west-facing arrays (covering an east–west facing roof, for example) are commonly deployed. Even though such installations will not produce the maximum possible average power from the individual solar panels, the cost of the panels is now usually cheaper than the tracking mechanism and they can provided more economically valuable power during morning and evening peak demands than north or south facing systems.[19]

Inverters

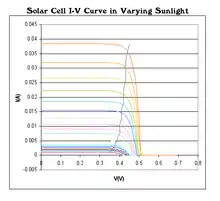

In general with solar panels, if not enough current is taken from PVs, then power isn't maximised. If too much current is taken then the voltage collapses. The optimum current draw depends on the amount of sunlight striking the panel. Solar panel capacity is specified by the MPP (maximum power point) value of solar panels in full sunlight.

- Solar inverters convert the DC power to AC power by performing the process of maximum power point tracking (MPPT): solar inverter samples the output Power (I-V curve) from the solar cell and applies the proper resistance (load) to solar cells to obtain maximum power.

- MPP (Maximum power point) of the solar panel consists of MPP voltage (V mpp) and MPP current (I mpp): it is a capacity of the solar panel and the higher value can make higher MPP.

Solar panels are wired to inverters in parallel or series (a 'string'). In string connections the voltages of the modules add, but the current is determined by the lowest performing panel. This is known as the "Christmas light effect". In parallel connections the voltages must be the same to work, but currents add. Arrays are connected up to meet the voltage requirements of the inverters and to not greatly exceed the current limits.

Micro-inverters work independently to enable each panel to contribute its maximum possible output for a given amount of sunlight, but can be more expensive.[20]

Connectors

Outdoor solar panels usually include MC4 connectors. Automotive solar panels may also include an auxiliary power outlet and/or USB adapter. Indoor panels (including solar pv glasses, thin films and windows) can integrate microinverter (AC Solar panels).

Efficiency

.png.webp)

Each module is rated by its DC output power under standard test conditions (STC) and hence the on field output power might vary. Power typically ranges from 100 to 365 Watts (W). The efficiency of a module determines the area of a module given the same rated output – an 8% efficient 230 W module will have twice the area of a 16% efficient 230 W module. Some commercially available solar modules exceed 24% efficiency.[22][23] Currently, the best achieved sunlight conversion rate (solar module efficiency) is around 21.5% in new commercial products[24] typically lower than the efficiencies of their cells in isolation. The most efficient mass-produced solar modules have power density values of up to 175 W/m2 (16.22 W/ft2).[25]

The current versus voltage curve of a module gives us useful information about its electrical performance.[26] Manufacturing processes often cause differences in the electrical parameters of different modules photovoltaic, even in cells of the same type. Therefore, only the experimental measurement of the I–V curve allows us to accurately establish the electrical parameters of a photovoltaic device. This measurement provides highly relevant information for the design, installation and maintenance of photovoltaic systems. Generally, the electrical parameters of photovoltaic modules are measured by indoor tests. However, outdoor testing has important advantages such as no expensive artificial light source required, no sample size limitation, and more homogeneous sample illumination.

Scientists from Spectrolab, a subsidiary of Boeing, have reported development of multi-junction solar cells with an efficiency of more than 40%, a new world record for solar photovoltaic cells.[27] The Spectrolab scientists also predict that concentrator solar cells could achieve efficiencies of more than 45% or even 50% in the future, with theoretical efficiencies being about 58% in cells with more than three junctions.

Capacity factor of solar panels is limited primarily by geographic latitude and varies significantly depending on cloud cover, dust, day length and other factors. In the United Kingdom, seasonal capacity factor ranges from 2% (December) to 20% (July), with average annual capacity factor of 10-11%, while in Spain the value reaches 18%.[28] Globally, capacity factor for utility-scale PV farms was 16.1% in 2019.[29]

Radiation-dependent efficiency

Depending on construction, photovoltaic modules can produce electricity from a range of frequencies of light, but usually cannot cover the entire solar radiation range (specifically, ultraviolet, infrared and low or diffused light). Hence, much of the incident sunlight energy is wasted by solar modules, and they can give far higher efficiencies if illuminated with monochromatic light. Therefore, another design concept is to split the light into six to eight different wavelength ranges that will produce a different color of light, and direct the beams onto different cells tuned to those ranges.[30] This has been projected to be capable of raising efficiency by 50%.

Aluminum nanocylinders

Research by Imperial College London has shown that solar panel efficiency is improved by studding the light-receiving semiconductor surface with aluminum nanocylinders, similar to the ridges on Lego blocks. The scattered light then travels along a longer path in the semiconductor, absorbing more photons to be converted into current. Although these nanocylinders have been used previously (aluminum was preceded by gold and silver), the light scattering occurred in the near-infrared region and visible light was absorbed strongly. Aluminum was found to have absorbed the ultraviolet part of the spectrum, while the visible and near-infrared parts of the spectrum were found to be scattered by the aluminum surface. This, the research argued, could bring down the cost significantly and improve the efficiency as aluminum is more abundant and less costly than gold and silver. The research also noted that the increase in current makes thinner film solar panels technically feasible without "compromising power conversion efficiencies, thus reducing material consumption".[31]

Technology

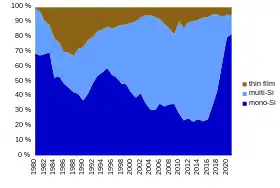

Most solar modules are currently produced from crystalline silicon (c-Si) solar cells made of polycrystalline and monocrystalline silicon.[32] In 2013, crystalline silicon accounted for more than 90 percent of worldwide PV production, while the rest of the overall market is made up of thin-film technologies using cadmium telluride, CIGS and amorphous silicon[33]

Emerging, third generation solar technologies use advanced thin-film cells. They produce a relatively high-efficiency conversion for a lower cost compared with other solar technologies. Also, high-cost, high-efficiency, and close-packed rectangular multi-junction (MJ) cells are usually used in solar panels on spacecraft, as they offer the highest ratio of generated power per kilogram lifted into space. MJ-cells are compound semiconductors and made of gallium arsenide (GaAs) and other semiconductor materials. Another emerging PV technology using MJ-cells is concentrator photovoltaics ( CPV ).

Thin film

In rigid thin-film modules, the cell and the module are manufactured on the same production line. The cell is created on a glass substrate or superstrate, and the electrical connections are created in situ, a so-called "monolithic integration." The substrate or superstrate is laminated with an encapsulant to a front or back sheet, usually another sheet of glass. The main cell technologies in this category are cadmium telluride (CdTe), amorphous silicon (a-Si), a-Si+uc-Si tandem, or copper indium gallium selenide (CIGS). Amorphous silicon has a sunlight conversion rate of 6–12%.

Flexible thin film cells and modules are created on the same production line by depositing the photoactive layer and other necessary layers on a flexible substrate. If the substrate is an insulator (e.g. polyester or polyimide film) then monolithic integration can be used. If it is a conductor then another technique for electrical connection must be used. The cells are assembled into modules by laminating them to a transparent colourless fluoropolymer on the front side (typically ETFE or FEP) and a polymer suitable for bonding to the final substrate on the other side.

Performance and degradation

Module performance is generally rated under standard test conditions (STC): irradiance of 1,000 W/m2, solar spectrum of AM 1.5 and module temperature at 25 °C.[34] The actual voltage and current output of the module changes as lighting, temperature and load conditions change, so there is never one specific voltage at which the module operates. Performance varies depending on geographic location, time of day, the day of the year, amount of solar irradiance, direction and tilt of modules, cloud cover, shading, soiling, state of charge, and temperature. Performance of a module or panel can be measured at different time intervals with a DC clamp meter or shunt and logged, graphed, or charted with a chart recorder or data logger.

For optimum performance, a solar panel needs to be made of similar modules oriented in the same direction perpendicular to direct sunlight. Bypass diodes are used to circumvent broken or shaded panels and optimize output. These bypass diodes are usually placed along groups of solar cells to create a continuous flow.[35]

Electrical characteristics include nominal power (PMAX, measured in W), open-circuit voltage (VOC), short-circuit current (ISC, measured in amperes), maximum power voltage (VMPP), maximum power current (IMPP), peak power, (watt-peak, Wp), and module efficiency (%).

Open-circuit voltage or VOC is the maximum voltage the module can produce when not connected to an electrical circuit or system.[36] VOC can be measured with a voltmeter directly on an illuminated module's terminals or on its disconnected cable.

The peak power rating, Wp, is the maximum output under standard test conditions (not the maximum possible output). Typical modules, which could measure approximately 1 by 2 metres (3 ft × 7 ft), will be rated from as low as 75 W to as high as 600 W, depending on their efficiency. At the time of testing, the test modules are binned according to their test results, and a typical manufacturer might rate their modules in 5 W increments, and either rate them at +/- 3%, +/-5%, +3/-0% or +5/-0%.[37][38][39]

Influence of temperature

The performance of a photovoltaic (PV) module depends on the environmental conditions, mainly on the global incident irradiance G in the plane of the module. However, the temperature T of the p–n junction also influences the main electrical parameters: the short circuit current ISC, the open circuit voltage VOC and the maximum power Pmax. In general, it is known that VOC shows a significant inverse correlation with T, while for ISC this correlation is direct, but weaker, so that this increase does not compensate for the decrease in VOC. As a consequence, Pmax decreases when T increases. This correlation between the power output of a solar cell and the working temperature of its junction depends on the semiconductor material, and is due to the influence of T on the concentration, lifetime, and mobility of the intrinsic carriers, i.e., electrons and gaps. inside the photovoltaic cell.

Temperature sensitivity is usually described by temperature coefficients, each of which expresses the derivative of the parameter to which it refers with respect to the junction temperature. The values of these parameters can be found in any data sheet of the photovoltaic module; are the following:

- β: VOC variation coefficient with respect to T, given by ∂VOC/∂T.

- α: Coefficient of variation of ISC with respect to T, given by ∂ISC/∂T.

- δ: Coefficient of variation of Pmax with respect to T, given by ∂Pmax/∂T.

Techniques for estimating these coefficients from experimental data can be found in the literature[40]

Degradation

The ability of solar modules to withstand damage by rain, hail, heavy snow load, and cycles of heat and cold varies by manufacturer, although most solar panels on the U.S. market are UL listed, meaning they have gone through testing to withstand hail.[41]

Potential-induced degradation (also called PID) is a potential-induced performance degradation in crystalline photovoltaic modules, caused by so-called stray currents.[42] This effect may cause power loss of up to 30%.[43]

The largest challenge for photovoltaic technology is the purchase price per watt of electricity produced. Advancements in photovoltaic technologies have brought about the process of "doping" the silicon substrate to lower the activation energy thereby making the panel more efficient in converting photons to retrievable electrons.[44]

Chemicals such as boron (p-type) are applied into the semiconductor crystal in order to create donor and acceptor energy levels substantially closer to the valence and conductor bands.[45] In doing so, the addition of boron impurity allows the activation energy to decrease twenty-fold from 1.12 eV to 0.05 eV. Since the potential difference (EB) is so low, the boron is able to thermally ionize at room temperatures. This allows for free energy carriers in the conduction and valence bands thereby allowing greater conversion of photons to electrons.

The power output of a photovoltaic (PV) device decreases over time. This decrease is due to its exposure to solar radiation as well as other external conditions. The degradation index, which is defined as the annual percentage of output power loss, is a key factor in determining the long-term production of a photovoltaic plant. To estimate this degradation, the percentage of decrease associated with each of the electrical parameters. The individual degradation of a photovoltaic module can significantly influence the performance of a complete string. Furthermore, not all modules in the same installation decrease their performance at exactly the same rate. Given a set of modules exposed to long-term outdoor conditions, the individual degradation of the main electrical parameters and the increase in their dispersion must be considered. As each module tends to degrade differently, the behavior of the modules will be increasingly different over time, negatively affecting the overall performance of the plant.

There are several studies dealing with the power degradation analysis of modules based on different photovoltaic technologies available in the literature. According to a recent study,[46] the degradation of crystalline silicon modules is very regular, oscillating between 0.8% and 1.0% per year.

On the other hand, if we analyze the performance of thin-film photovoltaic modules, an initial period of strong degradation is observed (which can last several months and even up to 2 years), followed by a later stage in which the degradation stabilizes, being then comparable to that of crystalline silicon.[47] Strong seasonal variations are also observed in such thin-film technologies because the influence of the solar spectrum is much greater. For example, for modules of amorphous silicon, micromorphic silicon or cadmium telluride, we are talking about annual degradation rates for the first years of between 3% and 4%.[48] However, other technologies, such as CIGS, show much lower degradation rates, even in those early years.

Maintenance

Solar panel conversion efficiency, typically in the 20% range, is reduced by the accumulation of dust, grime, pollen, and other particulates on the solar panels, collectively referred to as soiling. "A dirty solar panel can reduce its power capabilities by up to 30% in high dust/pollen or desert areas", says Seamus Curran, associate professor of physics at the University of Houston and director of the Institute for NanoEnergy, which specializes in the design, engineering, and assembly of nanostructures.[49] The average soiling loss in the world in 2018 is estimated to be at least 3% – 4%.[50]

Paying to have solar panels cleaned is a good investment in many regions, as of 2019.[50] However, in some regions, cleaning is not cost-effective. In California as of 2013 soiling-induced financial losses were rarely enough to warrant the cost of washing the panels. On average, panels in California lost a little less than 0.05% of their overall efficiency per day.[51]

There are also occupational hazards with solar panel installation and maintenance. A 2015–2018 study in the UK investigated 80 PV-related incidents of fire, with over 20 "serious fires" directly caused by PV installation, including 37 domestic buildings and 6 solar farms. In 1⁄3 of the incidents a root cause was not established and in a majority of others was caused by poor installation, faulty product or design issues. The most frequent single element causing fires was the DC isolators.[52]

A 2021 study by kWh Analytics determined median annual degradation of PV systems at 1.09% for residential and 0.8% for non-residential ones, almost twice that previously assumed.[53] A PVEL module reliability study found an increasing trend in solar module failure rates with 30% of manufacturers experiencing safety failures related to junction boxes (growth from 20%) and 26% bill-of-materials failures (growth from 20%).[54]

Cleaning methods for solar panels can be divided into 5 groups: manual tools, mechanized tools (such as tractor mounted brushes), installed hydraulic systems (such as sprinklers), installed robotic systems, and deployable robots. Manual cleaning tools are by far the most prevalent method of cleaning, most likely because of the low purchase cost. However, in a Saudi Arabian study done in 2014, it was found that "installed robotic systems, mechanized systems, and installed hydraulic systems are likely the three most promising technologies for use in cleaning solar panels".[55]

Waste and recycling

There was 30 thousand tonnes of PV waste in 2021, and the annual amount was estimated by Bloomberg NEF to rise to more than 1 million tons by 2035 and more than 10 million by 2050.[56] Most parts of a solar module can be recycled including up to 95% of certain semiconductor materials or the glass as well as large amounts of ferrous and non-ferrous metals.[57] Some private companies and non-profit organizations are currently engaged in take-back and recycling operations for end-of-life modules.[58] EU law requires manufacturers to ensure their solar panels are recycled properly. Similar legislation is underway in Japan, India, and Australia.[59]

A 2021 study by Harvard Business Review indicates that, unless reused, by 2035 the discarded panels would outweigh new units by a factor of 2.56. They forecast the cost of recycling a single PV panel by then would reach $20–30, which would increase the LCOE of PV by a factor 4. Analyzing the US market, where no EU-like legislation exists as of 2021, HBR noted that without mandatory recycling legislation and with the cost of sending it to a landfill being just $1–2 there was a significant financial incentive to discard the decommissioned panels. The study assumed that consumers would replace panels half way through a 30 year lifetime to make a profit.[60] However prices of new panels increased in the year after the study.[61] A 2022 study found that modules were lasting longer than previously estimated, and said that might result in less PV waste than had been thought.[62]

Recycling possibilities depend on the kind of technology used in the modules:

- Silicon based modules: aluminum frames and junction boxes are dismantled manually at the beginning of the process. The module is then crushed in a mill and the different fractions are separated – glass, plastics and metals.[63] It is possible to recover more than 80% of the incoming weight.[64] This process can be performed by flat glass recyclers since morphology and composition of a PV module is similar to those flat glasses used in the building and automotive industry. The recovered glass, for example, is readily accepted by the glass foam and glass insulation industry.

- Non-silicon based modules: they require specific recycling technologies such as the use of chemical baths in order to separate the different semiconductor materials.[65] For cadmium telluride modules, the recycling process begins by crushing the module and subsequently separating the different fractions. This recycling process is designed to recover up to 90% of the glass and 95% of the semiconductor materials contained.[66] Some commercial-scale recycling facilities have been created in recent years by private companies.[67] For aluminium flat plate reflector: the trendiness of the reflectors has been brought up by fabricating them using a thin layer (around 0.016 mm to 0.024 mm) of aluminum coating present inside the non-recycled plastic food packages.[68]

Since 2010, there is an annual European conference bringing together manufacturers, recyclers and researchers to look at the future of PV module recycling.[69][70]

Production

| Module producer | Shipments in 2019 (GW)[71] |

|---|---|

| Jinko Solar | 14.2 |

| JA Solar | 10.3 |

| Trina Solar | 9.7 |

| LONGi Solar | 9.0 |

| Canadian Solar | 8.5 |

| Hanwha Q Cells | 7.3 |

| Risen Energy | 7.0 |

| First Solar | 5.5 |

| GCL System | 4.8 |

| Shunfeng Photovoltaic | 4.0 |

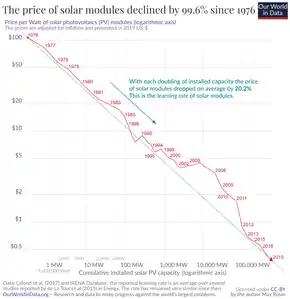

The production of PV systems has followed a classic learning curve effect, with significant cost reduction occurring alongside large rises in efficiency and production output.[72]

With over 100% year-on-year growth in PV system installation, PV module makers dramatically increased their shipments of solar modules in 2019. They actively expanded their capacity and turned themselves into gigawatt GW players.[73] According to Pulse Solar, five of the top ten PV module companies in 2019 have experienced a rise in solar panel production by at least 25% compared to 2019.[74]

The basis of producing solar panels revolves around the use of silicon cells.[75] These silicon cells are typically 10–20% efficient[76] at converting sunlight into electricity, with newer production models now exceeding 22%.[77] In order for solar panels to become more efficient, researchers across the world have been trying to develop new technologies to make solar panels more effective at turning sunlight into energy.[78]

In 2018, the world's top five solar module producers in terms of shipped capacity during the calendar year of 2018 were Jinko Solar, JA Solar, Trina Solar, Longi solar, and Canadian Solar.[79]

Price

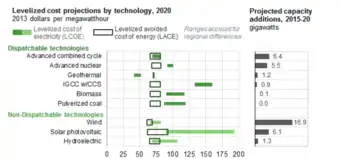

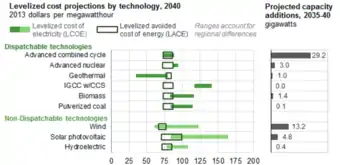

The price of solar electrical power has continued to fall so that in many countries it has become cheaper than ordinary fossil fuel electricity from the electricity grid since 2012, a phenomenon known as grid parity.[81]

Average pricing information divides in three pricing categories: those buying small quantities (modules of all sizes in the kilowatt range annually), mid-range buyers (typically up to 10 MWp annually), and large quantity buyers (self-explanatory—and with access to the lowest prices). Over the long term there is clearly a systematic reduction in the price of cells and modules. For example, in 2012 it was estimated that the quantity cost per watt was about US$0.60, which was 250 times lower than the cost in 1970 of US$150.[82][83] A 2015 study shows price/kWh dropping by 10% per year since 1980, and predicts that solar could contribute 20% of total electricity consumption by 2030, whereas the International Energy Agency predicts 16% by 2050.[84]

Real-world energy production costs depend a great deal on local weather conditions. In a cloudy country such as the United Kingdom, the cost per produced kWh is higher than in sunnier countries like Spain.

Following to RMI, Balance-of-System (BoS) elements, this is, non-module cost of non-microinverter solar modules (as wiring, converters, racking systems and various components) make up about half of the total costs of installations.

For merchant solar power stations, where the electricity is being sold into the electricity transmission network, the cost of solar energy will need to match the wholesale electricity price. This point is sometimes called 'wholesale grid parity' or 'busbar parity'.[81]

Some photovoltaic systems, such as rooftop installations, can supply power directly to an electricity user. In these cases, the installation can be competitive when the output cost matches the price at which the user pays for their electricity consumption. This situation is sometimes called 'retail grid parity', 'socket parity' or 'dynamic grid parity'.[87] Research carried out by UN-Energy in 2012 suggests areas of sunny countries with high electricity prices, such as Italy, Spain and Australia, and areas using diesel generators, have reached retail grid parity.[81]

Standards

Standards generally used in photovoltaic modules:

- IEC 61215 (crystalline silicon performance), 61646 (thin film performance) and 61730 (all modules, safety), 61853 (Photovoltaic module performance testing & energy rating)

- ISO 9488 Solar energy—Vocabulary.

- UL 1703 from Underwriters Laboratories

- UL 1741 from Underwriters Laboratories

- UL 2703 from Underwriters Laboratories

- CE mark

- Electrical Safety Tester (EST) Series (EST-460, EST-22V, EST-22H, EST-110).

Applications

There are many practical applications for the use of solar panels or photovoltaics. It can first be used in agriculture as a power source for irrigation. In health care solar panels can be used to refrigerate medical supplies. It can also be used for infrastructure. PV modules are used in photovoltaic systems and include a large variety of electric devices:

- Solar canals

- Photovoltaic power stations

- Rooftop solar PV systems

- Standalone PV systems

- Solar hybrid power systems

- Concentrated photovoltaics

- Floating solar; water-borne solar panels

- Solar planes

- Solar-powered water purification

- Solar-pumped lasers

- Solar vehicles

- Solar panels on spacecraft and space stations

Limitations

Impact on electricity network

With the increasing levels of rooftop photovoltaic systems, the energy flow becomes 2-way. When there is more local generation than consumption, electricity is exported to the grid. However, an electricity network traditionally is not designed to deal with the 2- way energy transfer. Therefore, some technical issues may occur. For example, in Queensland Australia, more than 30% of households used rooftop PV by the end of 2017. The duck curve appeared often for a lot of communities from 2015 onwards. An over-voltage issue may result as the electricity flows from PV households back to the network.[88] There are solutions to manage the over voltage issue, such as regulating PV inverter power factor, new voltage and energy control equipment at the electricity distributor level, re-conducting the electricity wires, demand side management, etc. There are often limitations and costs related to these solutions.

When electric networks are down, such as during the October 2019 California power shutoff, solar panels are often insufficient to fully provide power to a house or other structure, because they are designed to supply power to the grid, not directly to homes.[89]

Implication onto electricity bill management and energy investment

There is no silver bullet in electricity or energy demand and bill management, because customers (sites) have different specific situations, e.g. different comfort/convenience needs, different electricity tariffs, or different usage patterns. Electricity tariff may have a few elements, such as daily access and metering charge, energy charge (based on kWh, MWh) or peak demand charge (e.g. a price for the highest 30min energy consumption in a month). PV is a promising option for reducing energy charge when electricity price is reasonably high and continuously increasing, such as in Australia and Germany. However, for sites with peak demand charge in place, PV may be less attractive if peak demands mostly occur in the late afternoon to early evening, for example residential communities. Overall, energy investment is largely an economical decision and it is better to make investment decisions based on systematical evaluation of options in operational improvement, energy efficiency, onsite generation and energy storage.[90][91]

Solar module quality assurance

Solar module quality assurance involves testing and evaluating solar cells and Solar Panels to ensure the quality requirements of them are met. Solar modules (or panels) are expected to have a long service life between 20 and 40 years.[92] They should continually and reliably convey and deliver the power anticipated. modules presented to a wide exhibit of climate conditions alongside use in various temperatures. Solar modules can be tested through a combination of physical tests, laboratory studies, and numerical analyses.[93] Furthermore, solar modules need to be assessed throughout the different stages of their life cycle. Various companies such as Southern Research Energy & Environment, SGS Consumer Testing Services, TÜV Rheinland, Sinovoltaics, Clean Energy Associates (CEA), CSA Solar International and Enertis provide services in solar module quality assurance."The implementation of consistent traceable and stable manufacturing processes becomes mandatory to safeguard and ensure the quality of the PV Modules" [94]

Stages of testing

The lifecycle stages of testing solar modules can include: the Conceptual phase, manufacturing phase, transportation and installation, commissioning phase, and the in-service phase. Depending on the test phase, different test principles may apply.

Conceptual phase

The first stage can involve design verification where the expected output of the module is tested through computer simulation. Further, the modules ability to withstand natural environment conditions such as temperature, rain, hail, snow, corrosion, dust, lightning, horizon and near-shadow effects is tested. The layout for design and construction of the module and the quality of components and installation can also be tested at this stage.

Manufacturing phase

Inspecting manufacturers of components is carried through visitation. The inspection can include assembly checks, material testing supervision and Non Destructive Testing (NDT). Certification is carried our according to ANSI/UL1703, IEC 17025, IEC 61215, IEC 61646, IEC 61701 and IEC 61730-1/-2.

Transportation and installation phase

Inspections include pre-dispatch inspection, dimensional control, visual control, and damage control. Documentation and certificates should also be reviewed.

Commissioning phase and in-service phase

Solar module specialists will ensure that the production has followed correct procedure and ensure there is a save start up. The in-service phase involves regular inspections of the solar modules to confirm they are performing.

AC module

An AC module is a photovoltaic module which has a small AC inverter mounted onto its back side which produces AC power with no external DC connector.

AC modules are defined by Underwriters Laboratories as the smallest and most complete system for harvesting solar energy.[95]

See also

- Daisy chain (electrical engineering)

- Digital modeling and fabrication

- Domestic energy consumption

- Grid-tied electrical system

- Growth of photovoltaics

- MC4 connector

- Solar charger

- Solar cooker

- Solar still

- Junction box

References

- "April 25, 1954: Bell Labs Demonstrates the First Practical Silicon Solar Cell". APS News. American Physical Society. 18 (4). April 2009.

- Christian, M. "The history of the invention of the solar panel summary". Engergymatters.com. Energymatters.com. Retrieved 25 January 2019.

- Adams, William Grylls; Day, R. E. (1 January 1877). "IX. The action of light on selenium". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. 167: 313–316. doi:10.1098/rstl.1877.0009. ISSN 0261-0523.

- Meyers, Glenn (31 December 2014). "Photovoltaic Dreaming 1875--1905: First Attempts At Commercializing PV". cleantechnica.com. Sustainable Enterprises Media Inc. CleanTechnica. Retrieved 7 September 2018.

- Ohl, Russell (27 May 1941). "Light-sensitive electric device". Retrieved 7 September 2018.

- Kifilideen, Osanyinpeju; Adewole, Aderinlewo; Adetunji, Olayide; Emmanuel, Ajisegiri (2018). "Performance Evaluation of Mono-Crystalline Photovoltaic Panels in Funaab,Alabata, Ogun State, Nigeria Weather Condition". International Journal of Innovations in Engineering Research and Technology. 5 (2): 8–20.

- Kinsella, Pat (3 June 2021). "Are solar chargers worth it: a useful tool or a flash in the pan gimmick?". advnture.com. Retrieved 16 February 2022.

- "Solar Electronics, Panel Integration and the Bankability Challenge". Greentech Media. 23 August 2012. Retrieved 13 January 2014.

- "Solar Industry Data". SEIA. Retrieved 13 January 2014.

- "California Rooftop Photovoltaic (PV) Resource Assessment and Growth Potential by County" (PDF). California Energy Commission. September 2007. Archived from the original (PDF) on 13 December 2013. Retrieved 28 September 2022.

- "Solar Module OEMs Seeking Advantage With Inverter Electronics". Greentech Media. 23 October 2012. Retrieved 13 January 2014.

- "Leading Solar Module OEMs To Display Next-generation Tigo Energy Technology During PV Expo Japan". Tigo Energy. 28 February 2012. Retrieved 13 January 2014.

- SolarProfessional.com Ground-Mount PV Racking Systems March 2013

- Massachusetts Department of Energy Resources Ground-Mounted Solar Photovoltaic Systems, December 2012

- "A Guide To Photovoltaic System Design And Installation". ecodiy.org. Retrieved 26 July 2011.

- Shingleton, J. "One-Axis Trackers – Improved Reliability, Durability, Performance, and Cost Reduction" (PDF). National Renewable Energy Laboratory. Retrieved 30 December 2012.

- Mousazadeh, Hossain; et al. "A review of principle and sun-tracking methods for maximizing" (PDF). Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 13 (2009) 1800–1818. Elsevier. Retrieved 30 December 2012.

- "Optimum Tilt of Solar Panels". MACS Lab. Retrieved 19 October 2014.

- Perry, Keith (28 July 2014). "Most solar panels are facing the wrong direction, say scientists". The Daily Telegraph. Archived from the original on 11 January 2022. Retrieved 9 September 2018.

- "Micro Inverters for Residential Solar Arrays". Retrieved 10 May 2017.

- NREL (1 April 2022). "Champion Photovoltaic Module Efficiency Plot" (PDF). National Renewable Energy Laboratory. Retrieved 6 April 2022.

- Ulanoff, Lance (2 October 2015). "Elon Musk and SolarCity unveil 'world's most efficient' solar panel". Mashable. Retrieved 9 September 2018.

- da Silva, Wilson (17 May 2016). "Milestone in solar cell efficiency achieved". ScienceDaily. Retrieved 9 September 2018.

A new solar cell configuration developed by engineers at the University of New South Wales has pushed sunlight-to-electricity conversion efficiency to 34.5% -- establishing a new world record for unfocused sunlight and nudging closer to the theoretical limits for such a device.

- "SunPower e20 Module". 25 July 2014.

- "HIT® Photovoltaic Module" (PDF). Sanyo / Panasonic. Retrieved 25 November 2016.

- Piliougine, M.; Carretero, J.; Mora-López, L.; Sidrach‐de‐Cardona, M. (2011). Experimental system for current–voltage curve measurement of photovoltaic modules under outdoor conditions. Progress in Photovoltaics. Vol. 19. pp. 591–602. doi:10.1002/pip.1073. S2CID 96904811.

- KING, R.R., et al., Appl. Phys. Letters 90 (2007) 183516.

- Mearns, Euan (20 October 2015). "UK Solar PV Vital Statistics". Energy Matters. Retrieved 14 July 2021.

- "Solar PV capacity factor globally 2020". Statista. Retrieved 14 July 2021.

- Orcutt, Mike. "Managing Light To Increase Solar Efficiency". MIT Technology Review. Archived from the original on 20 February 2016. Retrieved 14 March 2018.

- "Improving the efficiency of solar panels". The Hindu. 24 October 2013. Retrieved 24 October 2013.

- "Advantages of Monocrystalline Flexible Solar Panel". Sun Gold Solar. 14 May 2017. Retrieved 22 July 2020.

- Photovoltaics Report, Fraunhofer ISE, 28 July 2014, pages 18,19

- Dunlop, James P. (2012). Photovoltaic systems. National Joint Apprenticeship and Training Committee for the Electrical Industry (3rd ed.). Orland Park, IL: American Technical Publishers, Inc. ISBN 978-1-935941-05-7. OCLC 828685287.

- Bowden, Stuart; Honsberg, Christiana. "Bypass Diodes". Photovoltaic Education. Retrieved 29 June 2021.

- "Open-Circuit Voltage (Battery)". Electrical School. 13 June 2018. Retrieved 30 June 2021.

- "REC Alpha Black Series Factsheet" (PDF).

- "TSM PC/PM14 Datasheet" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 29 October 2013. Retrieved 4 June 2012.

- "LBS Poly 260 275 Data sheet" (PDF). Retrieved 9 January 2018.

- Piliougine, M.; Oukaja, A.; Sidrach‐de‐Cardona, M.; Spagnuolo, G. (2021). Temperature coefficients of degraded crystalline silicon photovoltaic modules at outdoor conditions. Progress in Photovoltaics. Vol. 29. pp. 558–570. doi:10.1002/pip.3396. S2CID 233976803.

- "Are Solar Panels Affected by Weather?". Energy Informative. Retrieved 14 March 2018.

- "Solarplaza Potential Induced Degradation: Combatting a Phantom Menace". solarplaza.com. Retrieved 4 September 2017.

- (www.inspire.cz), INSPIRE CZ s.r.o. "What is PID? – eicero". eicero.com. Retrieved 4 September 2017.

- "How Solar Cells Work". HowStuffWorks. April 2000. Retrieved 9 December 2015.

- "Bonding in Metals and Semiconductors". 2012books.lardbucket.org. Retrieved 9 December 2015.

- Piliougine, M.; Oukaja, A.; Sánchez-Friera, P.; Petrone, G.; Sánchez-Pacheco, J.F.; Spagnuolo, G.; Sidrach-de-Cardona, M. (2021). Analysis of the degradation of single-crystalline silicon modules after 21 years of operation. Progress in Photovoltaics. Vol. 29. pp. 907–919. doi:10.1002/pip.3409. S2CID 234831264.

- Piliougine, M.; Oukaja, A.; Sidrach‐de‐Cardona, M.; Spagnuolo, G. (2022). Analysis of the degradation of amorphous silicon-based modules after 11 years of exposure by means of IEC60891:2021 procedure 3. Progress in Photovoltaics. Vol. 30. pp. 1176–1187. doi:10.1002/pip.3567. hdl:10630/24064. S2CID 248487635.

- Piliougine, M.; Sánchez-Friera, P.; Petrone, G.; Sánchez-Pacheco, J.F.; Spagnuolo, G.; Sidrach-de-Cardona, M. (2022). "New model to study the outdoor degradation of thin-film photovoltaic modules". Renewable Energy. 193: 857–869. doi:10.1016/j.renene.2022.05.063. S2CID 248926054.

- Crawford, Mike (October 2012). "Self-Cleaning Solar Panels Maximize Efficiency". The American Society of Mechanical Engineers. ASME. Retrieved 15 September 2014.

- Ilse K, Micheli L, Figgis BW, Lange K, Dassler D, Hanifi H, Wolfertstetter F, Naumann V, Hagendorf C, Gottschalg R, Bagdahn J (2019). "Techno-Economic Assessment of Soiling Losses and Mitigation Strategies for Solar Power Generation". Joule. 3 (10): 2303–2321. doi:10.1016/j.joule.2019.08.019.

- Patringenaru, Ioana (August 2013). "Cleaning Solar Panels Often Not Worth the Cost, Engineers at UC San Diego Find". UC San Diego News Center. UC San Diego News Center. Retrieved 31 May 2015.

- "Fire incidents involving solar panels". GOV.UK. Retrieved 22 June 2021.

- "Built solar assets are 'chronically underperforming' and modules degrading faster than expected, research finds". PV Tech. 8 June 2021. Retrieved 22 June 2021.

- "Solar module failure rates continue to rise as record number of manufacturers recognised in PVEL Module Reliability Scorecard". PV Tech. 26 May 2021. Retrieved 22 June 2021.

- Alshehri, Ali; Parrott, Brian; Outa, Ali; Amer, Ayman; Abdellatif, Fadl; Trigui, Hassane; Carrasco, Pablo; Patel, Sahejad; Taie, Ihsan (December 2014). "Dust mitigation in the desert: Cleaning mechanisms for solar panels in arid regions". 2014 Saudi Arabia Smart Grid Conference (SASG): 1–6. doi:10.1109/SASG.2014.7274289. ISBN 978-1-4799-6158-0. S2CID 23216963.

- Holger, Dieter (5 May 2022). "The Solar Boom Will Create Millions of Tons of Junk Panels". Wall Street Journal. ISSN 0099-9660. Retrieved 14 October 2022.

- Lisa Krueger "Overview of First Solar's Module Collection and Recycling Program" (PDF). Brookhaven National Laboratory p. 23. Retrieved 17 March 2017.

- Wambach, K. "A Voluntary Take Back Scheme and Industrial Recycling of Photovoltaic Modules" (PDF). Brookhaven National Laboratory p. 37. Retrieved 17 March 2017.

- Stone, Maddie (22 August 2020). "Solar Panels Are Starting to Die, Leaving Behind Toxic Trash". Wired. Retrieved 2 September 2020.

- "The Dark Side of Solar Power". Harvard Business Review. 18 June 2021. ISSN 0017-8012. Retrieved 22 June 2021.

- Stevens, Pippa (10 March 2022). "Solar costs jumped in 2021, reversing years of falling prices". CNBC. Retrieved 15 September 2022.

- "Working Out the Details of a Circular Solar Economy". www.nrel.gov. Retrieved 15 September 2022.

- Cynthia, Latunussa (9 October 2015). "Solar Panels can be recycled – BetterWorldSolutions – The Netherlands". BetterWorldSolutions – The Netherlands. Retrieved 29 April 2018.

- Latunussa, Cynthia E.L.; Ardente, Fulvio; Blengini, Gian Andrea; Mancini, Lucia (2016). "Life Cycle Assessment of an innovative recycling process for crystalline silicon photovoltaic panels". Solar Energy Materials and Solar Cells. 156: 101–11. doi:10.1016/j.solmat.2016.03.020.

- Wambach. 1999. p. 17

- Krueger. 1999. p. 23

- Wambach. 1999. p. 23

- Sonu, Mishra (21 December 2017). "Enhanced radiation trapping technique using low-cost aluminium flat plate reflector a performance analysis on solar PV modules". 2017 2nd International Conference for Convergence in Technology (I2CT). pp. 416–420. doi:10.1109/I2CT.2017.8226163. ISBN 978-1-5090-4307-1. S2CID 45196530.

- "First Breakthrough in Solar Photovoltaic Module Recycling, Experts Say". European Photovoltaic Industry Association. Archived from the original on 12 May 2013. Retrieved 1 January 2011.

- "3rd International Conference on PV Module Recycling". PV CYCLE. Archived from the original on 10 December 2012. Retrieved 1 October 2012.

- "LONGi: Who Are They And Why Do We Use Them". Pulse Solar. 5 August 2020.

- Harford, Tim (11 September 2019). "Can solar power shake up the energy market?". Retrieved 24 October 2019.

- "Solar PV Project Report | Helical Power". www.helicalpower.com.

- "LONGi: Who Are They And Why Do We Use Them". Pulse Solar. Retrieved 18 June 2020.

- "How Do Solar Panels Work?". Commercial Solar Australia. 5 September 2020.

- "Grand Challenges Make Solar Energy Economical". engineeringchallenges.org.

- "SolarCity Press Release". 2 October 2015. Retrieved 20 April 2017.

- Giges, Nancy (April 2014). "Making Solar Panels More Efficient". ASME.org. Retrieved 9 September 2018.

- "Top 10 solar module suppliers in 2018". PV Tech. 23 January 2019. Retrieved 24 October 2019.

- "Swanson's Law and Making US Solar Scale Like Germany". Greentech Media. 24 November 2014.

- Morgan Baziliana; et al. (17 May 2012). Re-considering the economics of photovoltaic power. UN-Energy (Report). United Nations. Archived from the original on 16 May 2016. Retrieved 20 November 2012.

- ENF Ltd. (8 January 2013). "Small Chinese Solar Manufacturers Decimated in 2012 | Solar PV Business News | ENF Company Directory". Enfsolar.com. Retrieved 29 August 2013.

- Harnessing Light. National Research Council. 1997. p. 162. doi:10.17226/5954. ISBN 978-0-309-05991-6.

- Farmer, J. Doyne; Lafond, François (2016). "How predictable is technological progress?". Research Policy. 45 (3): 647–65. arXiv:1502.05274. doi:10.1016/j.respol.2015.11.001. S2CID 154564641.

- MacDonald, A. E., Clack, C. T., Alexander, A., Dunbar, A., Wilczak, J., & Xie, Y. (2016). Future cost-competitive electricity systems and their impact on US CO 2 emissions. Nature Climate Change, 6(5), 526.

- MacDonald, A. E., Clack, C. T., Alexander, A., Dunbar, A., Wilczak, J., & Xie, Y. (2016). Future cost-competitive electricity systems and their impact on US CO 2 emissions. Nature Climate Change, 6(5), 526.

- "Solar Photovoltaics competing in the energy sector – On the road to competitiveness" (PDF). EPIA. Archived from the original (PDF) on 26 February 2013. Retrieved 1 August 2012.

- Miller, Wendy; Liu, Aaron; Amin, Zakaria; Wagner, Andreas (2018). "Power Quality and Rooftop-Photovoltaic Households: An Examination of Measured Data at Point of Customer Connection". Sustainability. 10 (4): 1224. doi:10.3390/su10041224.

- Martin, Chris (10 October 2019). "Californians Learning That Solar Panels Don't Work in Blackouts". Bloomberg. New York NY: Bloomberg LP.

- "Solutions for reducing facility electricity costs". Australian Ageing Agenda. 27 October 2017. Retrieved 12 August 2022.

- Miller, Wendy; Liu, Lei Aaron; Amin, Zakaria; Gray, Matthew (2018). "Involving occupants in net-zero-energy solar housing retrofits: An Australian sub-tropical case study". Solar Energy. 159: 390–404. Bibcode:2018SoEn..159..390M. doi:10.1016/j.solener.2017.10.008.

- Dickie, P.M. (1999). Regional Workshop on Solar Power Generation Using Photovoltaic Technology. DIANE publishing. p. 120. ISBN 9780788182648.

- Hough, T.P. (2006). Trends in solar energy research. Nova. p. 98. ISBN 9781594548666.

- Parra, Dr. Vicente / Dr. Ruperto Gómez (September 2018). "Implementing risk mitigation strategies through module factory and production inspections". PV Tech. 16: 25–28.

- UL1741 pp 17, Section 2.2

Bibliography

- Underwriters Laboratories (2005), UL 1741 Inverters, Converters, Controllers and Interconnection System Equipment for Use With Distributed Energy Resources, UL 1741, Northbrook, IL, p. 17