Spear-thrower

A spear-thrower, spear-throwing lever or atlatl (pronounced /ˈætlætəl/[1] or /ˈɑːtlɑːtəl/;[2] Nahuatl ahtlatl [ˈaʔt͡ɬat͡ɬ]) is a tool that uses leverage to achieve greater velocity in dart or javelin-throwing, and includes a bearing surface which allows the user to store energy during the throw.

.jpg.webp)

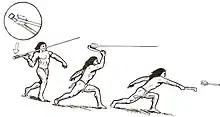

It may consist of a shaft with a cup or a spur at the end that supports and propels the butt of the spear. It's usually about as long as the user's arm or forearm. The user holds the spear-thrower in one hand, gripping near the end farthest from the cup. The user puts the butt end of the spear, or dart, in the cup, or grabs the spur with the end of the spear. The spear is much longer than the thrower. The user holds the spear parallel to the spear-thrower and going in the other direction. The user can hold the spear, with the index and thumb, with the same hand as the thrower, with the other fingers. The user reaches back with the spear pointed at the target. Then they make an overhand throwing motion with the thrower while letting go of the spear with the fingers.[3][4]

The dart is thrown by the action of the upper arm and wrist. The throwing arm together with the atlatl acts as a lever. The spear-thrower is a low-mass, fast-moving extension of the throwing arm, increasing the length of the lever. This extra length allows the thrower to impart force to the dart over a longer distance, thus imparting more energy and higher speeds.[5]

Common modern ball throwers (such as molded plastic arms used for throwing tennis balls for dogs to fetch) use the same principle.

A spear-thrower is a long-range weapon and can readily impart to a projectile speeds of over 150 km/h (93 mph).[6]

Spear-throwers appear very early in human history in several parts of the world, and have survived in use in traditional societies until the present day, as well as being revived in recent years for sporting purposes. In the United States, the Nahuatl word atlatl is often used for revived uses of spear-throwers (or the Mayan word hul'che); in Australia, the Dharug word woomera is used instead.

The ancient Greeks and Romans used a leather thong or loop, known as an ankule or amentum, as a spear-throwing device.[7] The Swiss arrow is a weapon that works similarly to amentum.

Design

Spear-thrower designs may include improvements such as thong loops to fit the fingers, the use of flexible shafts or stone balance weights. Dart shafts can be made thinner and highly flexible for added power and range, the fletching can be spiralized to add spin to the dart making it more stable and accurate. Darts resemble large arrows or small spears and are typically from 1.2 to 2.7 m (4 to 9 ft) in length and 9 to 16 mm (3/8" to 5/8") in diameter.

Another important improvement to the spear-thrower's design was the introduction of a small weight (between 60 and 80 grams) strapped to its midsection. Some atlatlists maintain that stone weights add mass to the shaft of the device, causing resistance to acceleration when swung and resulting in a more forceful and accurate launch of the dart. Others claim that spear-thrower weights add only stability to a cast, resulting in greater accuracy.

Based on previous work done by William S. Webb, William R. Perkins[8] claims that spear-thrower weights, commonly called "bannerstones", and characterized by a centered hole in a symmetrically shaped carved or ground stone, shaped wide and flat with a drilled hole and thus a little like a large wingnut, are an improvement to the design that created a silencing effect when swung. The use of the device would reduce the telltale "zip" of a swung atlatl to a more subtle "woof" sound that did not travel as far and was less likely to alert prey. Robert Berg's theory is that the bannerstone was carried by hunters as a spindle weight to produce string from natural fibers gathered while hunting, for the purpose of tying on fletching and hafting stone or bone points.[9]

Woomera

The woomera design is distinctly different from most other spear-throwers, in that it has a curved, hollow shape, which allows for it to be used for other purposes (in some cases) such as carrying food.

Artistic designs

Several Stone Age spear-throwers (usually now incomplete) are decorated with carvings of animals: the British Museum has a mammoth, and there is a hyena in France. Many pieces of decorated bone may have belonged to Bâtons de commandement.

The Aztec atlatl was often decorated with snake designs and feathers,[10] potentially evocative of its association with Ehecatl, the Aztec wind deity.[11]

History

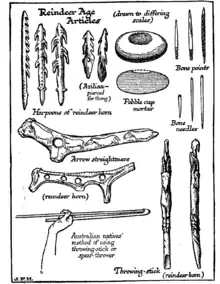

Wooden darts were known at least since the Middle Paleolithic (Schöningen, Torralba, Clacton-on-Sea and Kalambo Falls). While the spear-thrower is capable of casting a dart well over one hundred meters, it is most accurately used at distances of twenty meters or less. The spearthrower is believed to have been in use by Homo sapiens since the Upper Paleolithic (around 30,000 years ago).[12] Most stratified European finds come from the Magdalenian (late upper Palaeolithic). In this period, elaborate pieces, often in the form of animals, are common. The earliest secure data concerning atlatls have come from several caves in France dating to the Upper Paleolithic, about 21,000 to 17,000 years ago. The earliest known example is a 17,500-year-old Solutrean atlatl made of reindeer antler, found at Combe Saunière (Dordogne), France.[13] It is possible that the atlatl was invented earlier than this, as Mungo Man from 42,000 BP displays arthritis in his right elbow, a pathology referred to today as the "Atlatl elbow," resulting from many years of forceful torsion from using an atlatl.[14] At present there is no evidence for the use of atlatls in Africa. Peoples such as the Maasai and Khoi San throw spears without any aids, but its use in hunting is limited in comparison to the spear thrower since the animal must be very close and already immobile.

During the Ice Age, the atlatl was used by humans to hunt Megafauna. Ice Age Megafauna offered a large food supply when other game was limited, and the atlatl gave more power to pierce their thicker skin. In this time period, atlatls were usually made of wood or bone. Improvements made to spears' edge made it more efficient as well.[15]

In Europe, the spear-thrower was supplemented by the bow and arrow in the Epi-Paleolithic. Along with improved ease of use, the bow offered the advantage that the bulk of elastic energy is stored in the throwing device, rather than the projectile; arrow shafts can therefore be much smaller, and have looser tolerances for spring constant and weight distribution than atlatl darts. This allowed for more forgiving flint knapping: dart heads designed for a particular spear thrower tend to differ in mass by only a few percent. By the Iron Age, the amentum, a strap attached to the shaft, was the standard European mechanism for throwing lighter javelins. The amentum gives not only range, but also spin to the projectile.[16]

The spear-thrower was used by early Americans as well. It may have been introduced to America during the immigration across the Bering Land Bridge, and despite the later introduction of the bow and arrow, atlatl use was widespread at the time of first European contact. Atlatls are represented in the art of multiple pre-Columbian cultures, including the Basketmaker culture in the American Southwest, Maya in the Yucatán Peninsula, and Moche in the Andes of South America. Atlatls were especially prominent in the iconography of the warriors of the Teotihuacan culture of Central Mexico. A ruler from Teotihucan named Spearthrower Owl is an important figure described in Mayan stelae. Complete wooden spear-throwers have been found on dry sites in the western United States and in waterlogged environments in Florida and Washington. Several Amazonian tribes also used the atlatl for fishing and hunting. Some even preferred this weapon over the bow and arrow, and used it not only in combat but also in sports competitions. Such was the case with the Tarairiu, a Tapuya tribe of migratory foragers and raiders inhabiting the forested mountains and highland savannahs of Rio Grande do Norte in mid-17th-century Brazil. Anthropologist Harald Prins offers the following description:

The spear-thrower was an important part of life, hunting, and religion in the ancient Andes. The earliest known spear-thrower of the South Americas had a proximal handle piece and is commonly referred to as an estólica in Spanish references to indigenous Andean culture . Estólica and atlatl are therefore synonymous terms. The estólica is best known archaeologically from Nazca culture and the Inca civilization, but the earliest examples are known from associations with Chinchorro mummies.[17] The estólica is also known from Moche culture, including detailed respresentations on painted pottery, and in representations on textiles of the Wari culture[18]

The Andean estólica had a wooden body with a hook that was made of stone or metal. These hooks have been found at multiple highland sites including Cerro Baúl, a site of the Wari culture. In the Andes, the tips of darts were often capped with metal. Arrow points commonly had the same appearance as these Andean tips. The length of a common estòlica was about 50 cm. Estólica handles were commonly carved and modeled to represent real world accounts like animals and deities.[19]

Examples of estòlicas with no handle pieces have been interpreted as children's toys. Archaeologists found decorated examples in the Moche culture burial of the Lady of Cao at El Brujo in the Chicama valley. At her feet was a group of twenty-three atlatls with handle pieces that depicted birds. These “theatrical” estòlicas are different from normal weapons. They are much longer (80-100 cm) than the regular examples (50-60 cm). John Whittaker and Kathryn Kamp believe that they might have been part of a ceremony before the burial or symbolic references to indicate that the royal woman in the burial had been a warrior.

Estólicas are depicted along with maces, clubs, and shields on Moche vessels that illustrate warfare.[20] The atlatl appears in the artwork of Chavín de Huantar, such as on the Black and White Portal.

The atlatl, as used by these Tarairiu warriors, was unique in shape. About 88 cm (35 in) long and 3 to 4.5 cm (1+1⁄4 to 1+3⁄4 in) wide, this spear thrower was a tapering piece of wood carved of brown hard-wood. Well-polished, it was shaped with a semi-circular outer half and had a deep groove hollowed out to receive the end of the javelin, which could be engaged by a horizontal wooden peg or spur lashed with a cotton thread to the proximal and narrower end of the throwing board, where a few scarlet parrot feathers were tied for decoration. [Their] darts or javelins ... were probably made of a two-meter long wooden cane with a stone or long and serrated hard-wood point, sometimes tipped with poison. Equipped with their uniquely grooved atlatl, they could hurl their long darts from a great distance with accuracy, speed, and such deadly force that these easily pierced through the protective armor of the Portuguese or any other enemy.[21]

Among the Tlingit of Southeast Alaska, approximately one dozen very old elaborately carved specimens they call "shee áan" (sitting on a branch) remain in museum collections[22] and private collections, one having sold at auction for more than $100,000.

In September 1997, an atlatl dart fragment, carbon dated to 4360 ± 50 14C yr BP (TO 6870), was found in an ice patch on mountain Thandlät, the first of the southern Yukon Ice Patches to be studied.[23][24][25]: 363 [26]: 2

The people of New Guinea and Aboriginal people in Australia also use spear-throwers. In the mid Holocene,[27] Aboriginal people in Australia developed spear-throwers, known as woomeras.[28][29]

As well as its practical use as a hunting weapon, it may also have had social effects. John Whittaker, an anthropologist at Grinnell College, Iowa, suggests the device was a social equalizer in that it requires skill rather than muscle power alone. Thus women and children would have been able to participate in hunting.[6]

Whittaker said the stone-tipped projectiles from the Aztec atlatl were not powerful enough to penetrate Spanish steel plate armor, but they were strong enough to penetrate the mail, leather and cotton armor that most Spanish soldiers wore.[10] Whittaker said the Aztecs started their battles with atlatl darts followed with melee combat using the macuahuitl.[10]

Bâtons de commandement

Another type of Stone Age artefact that is sometimes excavated is the bâton de commandement. These are shorter, normally less than one foot long, and made of antler, with a hole drilled through them. When first found in the nineteenth century, they were interpreted by French archaeologists to be symbols of authority, like a modern Field Marshal's baton, and so named bâtons de commandement ("batons of command"). Though debate over their function continues, tests with replicas have found them, when used with a cord, very effective aids to spear or dart throwing.[30] Another theory is that they were "arrow-straighteners".

Bian Jian ("Spear sling")

Bian Jian (Chinese: 鞭箭, lit. 'Whip arrow') is a unique spear-thrower that was used during Song period. It can be described as a very long staff sling that throws a spear-sized dart instead of a rock-like projectile. It requires two operators unlike other spear-throwers. It should not be confused with another Bian Jian (邊箭).

Modern times

.jpg.webp)

In modern times, some people have resurrected the dart thrower for sports, often using the term atlatl, throwing either for distance and/or for accuracy. The World Atlatl Association was formed in 1987[31] to promote the atlatl.[32] Throws of almost 260 m (850 ft) have been recorded.[33] Colleges reported to field teams in this event include Grinnell College in Iowa, Franklin Pierce University in New Hampshire, Alfred University in New York, and the University of Vermont.[34]

Atlatls are sometimes used in modern times for hunting. In the U.S., the Pennsylvania Game Commission has given preliminary approval for legalization of the atlatl for hunting certain animals.[35] The animals that would be allowed to atlatl hunters have yet to be determined, but particular consideration has been given to deer. Currently, Alabama allows the atlatl for deer hunting, while a handful of other states list the device as legal for rough fish (those not sought for sport or food), some game birds and non-game mammals.[36] Starting in 2007, Missouri allowed use of the atlatl for hunting wildlife (excluding deer and turkey), and starting in 2010, also allowed deer hunting during the firearms portion of the deer season (except the muzzleloader portion).[37][38] Starting in 2012, Missouri allowed the use of atlatls during the fall archery deer and turkey hunting seasons and, starting in 2014, allowed the use of atlatls during the spring turkey hunting season as well.[39] Missouri also allows use of the atlatl for fishing, with some restrictions (similar to the restrictions for spearfishing and bowfishing).[40] The Nebraska Game and Parks Commission allows the use of atlatls for the taking of deer as of 2013.[41]

The woomera is still used today by some Aboriginal people for hunting in Australia. Yup'ik Eskimo hunters still use the atlatl, known locally as "nuqaq" (nook-ak), in villages near the mouth of the Yukon River for seal hunting.

Competitions

There are numerous atlatl competitions held every year, with spears and spear-throwers built using both ancient and modern materials. Events are often held at parks, such as Letchworth State Park in New York, Cahokia Mounds State Historic Site in Illinois, or Valley of Fire State Park in Nevada.[6] Atlatl associations around the world[42] host a number of local atlatl competitions. Chimney Point State Historic Site in Addison, Vermont hosts the annual Northeast Open Atlatl Championship. In 2009, the Fourteenth Annual Open Atlatl Championship was held on Saturday and Sunday, September 19 and 20. On the Friday before the Championship, a workshop was held to teach modern and traditional techniques of atlatl and dart construction, flint knapping, hafting stone points, and cordage making.[43] Competitions may be held in conjunction with other events, such as the Ohio Pawpaw Festival,[44] or at the Bois D'Arc Primitive Skills Gathering and Knap-in, held every September in southern Missouri.[45]

Atlatl events commonly include the International Standard Accuracy Competition (ISAC), in which contestants throw ten times at a bull's-eye target.[46] Other contests involving different distances or terrain may also be included, usually testing the atlatlist's accuracy rather than distance throwing.

Popular culture

In the sixth episode of the fourth season of the television competition Top Shot, the elimination round consisted of two contestants using the atlatl at ranges of 30, 45 and 60 feet.

An atlatl was the weapon of choice of a serial killer in the 2020 action-thriller The Silencing, where it is erroneously described as an illegal weapon.[47]

Lydia Demarek, a character in the popular fantasy novel series Brotherband, owns and often uses an atlatl.

See also

- Amentum

- Aztec warfare

- Hunter-gatherer societies

- Kestros

- Swiss arrow

- Woomera (spear-thrower)

References

- "atlatl". Oxford English Dictionary (Online ed.). Oxford University Press. (Subscription or participating institution membership required.)

- "atlatl". Dictionary.com Unabridged (Online). n.d.

- Archived at Ghostarchive and the Wayback Machine: "How to Throw an Atlatl and Dart". youtube.com. Retrieved 2021-06-30.

- Archived at Ghostarchive and the Wayback Machine: "The Atlatl: Most Underrated Stone Age Tool?". youtube.com. Retrieved 2021-06-30.

- "Atlatl History and Physics". Tasigh.org. Retrieved 2013-09-21.

- "Girls on top". The Economist. April 12, 2008.

- Blackmore, Howard L. (2000). Hunting Weapons: From the Middle Ages to the Twentieth Century. p. 103.

... the air'.31 A device which enabled all but the heaviest of spears to be cast a respectable distance was the spear thrower. ... It was known to the Greeks as the ankuli and to Romans as the amentum.3 The spear was rested in the hand and ...

- "Atlatls & Primitive Technology". Retrieved 2012-08-19.

- Berg, Robert S. (17 June 2005). "Bannerstones And How They Relate To The Atlatl". Retrieved 8 March 2018.

- "Mexicolore". Mexicolore. 21 December 2012. Retrieved 21 September 2013.

- Mexicolore's page on the atlatl, and its connection with Ehecatl

- McClellan, James Edward; Dorn, Harold (2006). Science and technology in world history: an introduction. Johns Hopkins University Press. p. 11. ISBN 978-0-8018-8360-6.

- Peregrine, Peter N.; Ember, Melvin (2001). "Europe". Encyclopedia of Prehistory. Vol. 4. Springer. ISBN 978-0-306-46258-0.

- "Mungo Lady and Mungo Man". mungo. n.d. Retrieved November 3, 2018.

- Toler, Pamela D. (30 October 2012). Mankind: The Story of All of Us. Running Press. p. 20. ISBN 978-0-7624-4703-9.

- Gardiner, E. Norman (1907). "Throwing the Javelin". The Journal of Hellenic Studies. 27: 249–273. doi:10.2307/624444. JSTOR 624444.

- Arriaza, Bernardo (1995). Beyond Death: The Chinchorro Mummies of Ancient Chile. Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution. ISBN 978-1560985129.

- Critchley, Zachary. "The Art of the Spearthrower: Understanding the Andean Estólica through Iconography". Retrieved 28 April 2021.

- Slater, Donald (2011). "Power Materialized: The Dart-Thrower as a Pan-Mesoamerican Status Marker". Ancient Mesoamerica. 22 (2): 371–388. doi:10.1017/S0956536111000277. S2CID 162483649. Retrieved 28 April 2021.

- Whittaker, John (2006). "Atlatl Use on Moche Pottery of Ancient Peru". The Newsletter of the World Atlatl Association, Inc. 19 (3).

- Prins, Harald E.L. (2010). "The Atlatl as Combat Weapon in 17th-Century Amazonia: Tapuya Indian Warriors in Dutch Colonial Brazil" (PDF). The Atlatl. 23 (2): 1–3. Archived from the original (PDF) on 29 February 2012. Retrieved 2013-05-08.

- "Fenimore Art Museum | Atlatl". Collections.fenimoreartmuseum.org. 8 December 1992. Archived from the original on 2013-09-23. Retrieved 21 September 2013.

- "Traditional Homeland". Kusawa Park Steering Committee. n.d. Archived from the original on 29 March 2017. Retrieved 2 December 2017.

- Kuzyk, G.W.; Russell, D.E.; Farnell, R.S.; Gotthardt, R.M.; Hare, P.G.; Blake, E. (1999). "In pursuit of prehistoric c caribou on Thandlät, southern Yukon" (PDF). Arctic. 52 (2): 214–219. doi:10.14430/arctic924.

- de la Cadena, Marisol; Starn, Orin, eds. (September 15, 2007). Indigenous Experience Today. Bloomsbury Academic. p. 384. ISBN 978-1845205195. Retrieved 2 December 2017.

- Hare, Greg (2011). The Frozen Past: The Yukon Ice Patches (PDF) (Report). Government of the Yukon. p. 36. ISBN 978-1-55362-509-4. Retrieved 2 December 2017.

- Laet, Sigfried J. de & International Commission for the New Edition of the History of the Scientific and Cultural Development of Mankind & International Commission for a History of the Scientific and Cultural Development of Mankind. History of mankind (1994). History of humanity. Routledge; Paris : Unesco, London; New York, p.1064

- Palter, John L. (1977). "Design and construction of Australian spear-thrower projectiles and hand-thrown spears". Archaeology & Physical Anthropology in Oceania. APA: 161–172.

- Cundy, B. J. (1989). "Formal variation in Australian spear and spearthrower technology". British Archaeological Reports. British Archaeological Reports Ltd. 546.

- Wescott, David, ed. (1999). Primitive Technology: A Book of Earth Skills. Society of Primitive Technology, Gibbs Smith. ISBN 9780879059118. Retrieved 21 September 2013 – via Google Books.

- "The World Atlatl Association: About Us". 10 May 2016. Retrieved 10 February 2017.

- "The World Atlatl Association: Modern sport". 12 May 2016. Retrieved 10 February 2017.

- "The Atlatl". Flight-toys.com. Retrieved 8 June 2009.

- "Our Towns: A College Team Takes Aim". Parade.com. 30 May 2010. Retrieved 21 September 2013.

- "Pennsylvania May Let Hunters Use Prehistoric Weapon". RedOrbit.com. 13 November 2005. Retrieved 8 June 2009.

- "Spear near in Pennsylvania? from espn.com". Sports.espn.go.com. 21 June 2006. Retrieved 8 June 2009.

- "2013 Firearms Deer Hunting | Missouri Department of Conservation". Mdc.mo.gov. 15 September 2013. Archived from the original on 21 May 2011. Retrieved 21 September 2013.

- Wang, Regina (28 September 2010). "Atlatl makes debut for Missouri deer season". Columbia Missourian. Archived from the original on 6 October 2010. Retrieved 21 September 2013.

- "Conservation Action: Meeting of the May 2011 Conservation Commission | Missouri Department of Conservation". Archived from the original on 16 November 2012. Retrieved 25 November 2011.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - "Missouri Department of Conservation, Wildlife Code: Sport Fishing: Seasons, Methods, Limits" (PDF). Sos.mo.gov. Retrieved 21 September 2013.

- "Whitetail and Mule Deer Hunting". State of Nebraska. Archived from the original on December 21, 2014. Retrieved December 21, 2014.

- "Atlatl Associations". Thunderbird Atlatl. Retrieved 2013-09-21.

- Archived September 5, 2009, at the Wayback Machine

- "2013 Ohio Pawpaw Festival". Ohiopawpawfest.com. Retrieved 2013-09-21.

- "Bois D' Arc Primitive Skills Gathering and Knap-in". Retrieved 2013-10-06.

- "ISAC Rules Package" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2017-02-11. Retrieved 2017-02-10.

- "Atlatl Madness's Atlatl Darts in a Movie!!! "The Silencing"". 21 July 2020. Retrieved 13 August 2020.

- Garrod, D. (1955). "Palaeolithic spear throwers". Proc. Prehist. Soc. 21: 21–35. doi:10.1017/s0079497x00017370.

- Hunter, W. (1992) "Reconstructing a Generic Basket Maker Atlatl", Bulletin of Primitive Technology, No. 4.

- Knecht, H. (1997) Projectile technology, New York, Plenum Press, 408 p. ISBN 0-306-45716-4

- Nuttall, Zelia (1891). The atlatl or spear-thrower of the ancient Mexicans. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Peabody Museum of American Archaeology and Ethnology. OCLC 3536622.

- Perkins, W. (1993) "Atlatl Weights, Function and Classification", Bulletin of Primitive Technology, No. 5.

- Prins, Harald E.L. (2010). The Atlatl as Combat Weapon in 17th-Century Amazonia: Tapuya Indian Warriors in Dutch Colonial Brazil. The Atlatl, Vol.23, No.2, pp. 1–3. http://waa.basketmakeratlatl.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/02/Tapuya-Atlatl-Article-by-Harald-Prins-25%5B%5D May 2010.pdf

- Stodiek, U. (1993) Zur Technik der jungpaläolithischen Speerschleuder (Tübingen).