Swedish-speaking population of Finland

The Swedish-speaking population of Finland (whose members are called by many names[Note 1]—see below; Swedish: finlandssvenskar; Finnish: suomenruotsalaiset) is a linguistic minority in Finland. They maintain a strong identity and are seen either as a separate cultural or ethnic group, while still being considered ethnic Finns,[Note 2][Note 3][Note 4] or as a distinct nationality.[Note 5] They speak Finland Swedish, which encompasses both a standard language and distinct dialects that are mutually intelligible with the dialects spoken in Sweden and, to a lesser extent, other Scandinavian languages.

| |

|---|---|

Flag of the Swedish-speaking Finns | |

| Total population | |

| 380,000[1] | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| 287,933 (2021)[2] | |

| 60,000–107,000[3][4] | |

| Languages | |

| Finland Swedish, Finnish | |

| Religion | |

| Lutheranism | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Swedes, Estonian Swedes | |

.svg.png.webp)

More than 17,000 Swedish-speaking Finns live in officially monolingual Finnish municipalities, and are thus not represented on the map.

According to Statistics Finland, Swedish is the mother tongue of about 260,000 people in mainland Finland and of about 26,000 people in Åland, a self-governing archipelago off the west coast of Finland, where Swedish speakers constitute a majority. Swedish-speakers comprise 5.2% of the total Finnish population[13] or about 4.9% without Åland. The proportion has been steadily diminishing since the early 19th century, when Swedish was the mother tongue of approximately 15% of the population and considered a prestige language.

According to a 2007 statistical analysis made by Fjalar Finnäs, the population of the minority group is stable,[14][15] and may even be increasing slightly in total numbers since more parents from bilingual families tend to register their children as Swedish speakers.[16] It is estimated that 70% of bilingual families—that is, ones with one parent Finnish-speaking and the other Swedish-speaking—register their children as Swedish-speaking.[17]

Terminology

The Swedish term finlandssvensk (literally 'Finland's-Swede'), which is used by the group itself, does not have an established English translation. The Society of Swedish Authors in Finland and the main political institutions for the Swedish-speaking minority, such as the Swedish People's Party and Swedish Assembly of Finland, use the expression Swedish-speaking population of Finland, but Swedish-speaking NGOs often use the term Finland-Swedes.[18]

The Research Institute for the Languages of Finland proposes Swedish-speaking Finns, Swedish Finns, or Finland-Swedes, the first of which is the sole form used on the institute's website. Some debators insist for the use of the more traditional English-language form, Finland-Swedes, as they view the labelling of them as Swedish-speaking Finns as a way of depriving them their ethnic affiliation, reducing it to merely a matter of language and de-emphasising the "Swedish part" of Finland-Swedish identity, i.e. their relations to Sweden.[Note 6][Note 7]

Among Finnish Americans the term Swede-Finn became dominant before the independence of Finland in 1917, and the term has remained common to the present, despite later immigrants tending to use different terms such as Finland-Swede.[21] The expressions Swedish-speaking Finns, Swedes of Finland, Finland Swedes, Finnish Swedes, and Swedish Finns are all used in academic literature.

History

Medieval Swedish colonisation

The first Swedish arrivals in Finland have often been linked to the putative First Swedish Crusade (ca. 1150) which, if it took place, served to expand Christianity and annex Finnish territories to the kingdom of Sweden. Simultaneously the growth of population in Sweden, together with lack of land, resulted in Swedish settlements in Southern and Western coastal areas of Finland.[Note 8][23] The Second Swedish Crusade against the Tavastians in the 13th century extended the Swedish settlements to Nyland (Uusimaa).[Note 9] During the 14th century, the population expansion from Sweden proper increasingly took the form of organised mass migration: the new settlers came in large numbers in large ships from various parts of Sweden's Eastern coast, from Småland to Hälsingland. Their departure from Sweden proper to Finland was encouraged and organized by the Swedish authorities.[Note 10] The coast of Ostrobothnia received large-scale Swedish settlements during the 13th and 15th centuries, in parallel with events that resulted in Swedish expansion to Norrland[Note 11] and Estonia's coastal area.

Debate about the origin of the Swedish-speaking population in Finland

The origin of the Swedish-speaking population in the territory that today constitutes Finland was a subject of fierce debate in the early 20th century as a part of the Finland's language strife. Some Finland-Swede scholars, such as Ralf Saxén, Knut Hugo Pipping and Tor Karsten, used place names in trying to prove that the Swedish settlement in Finland dates back to prehistoric times. Their views were opposed mainly by Heikki Ojansuu in the 1920s.[24][25]

In 1966, the historian Hämäläinen (as referenced by McRae 1993) addressed the strong correlation between the scholar's mother-tongue and the views on the Scandinavian settlement history of Finland.

"Whereas Finnish-speaking scholars tended to deny or minimize the presence of Swedish-speakers before the historically documented Swedish expeditions starting from the 12th century, Swedish-speaking scholars have found archeological and philological evidence for a continuous and Swedish or Germanic presence in Finland from pre-historic times."[26][Note 12]

Since the late 20th century, several Swedish-speaking philologists, archaeologists and historians from Finland have criticized the theories of Germanic/Scandinavian continuity in Finland.[28][29][30][31][32][33] Current research has established that the Swedish-speaking population and Swedish place names in Finland date to the Swedish colonisation of Nyland and Ostrobothnia coastal regions of Finland in the 12th and 13th centuries.[34][24][25]

Nationalism and language strife

The proportion of Swedish speakers in Finland has declined since the 18th century, when almost 20% spoke Swedish (these 18th-century statistics excluded Karelia and Kexholm County, which were ceded to Russia in 1743, and the northern parts of present-day Finland were counted as part of Norrland). When the Grand Duchy of Finland was formed and Karelia was reunited with Finland, the share of Swedish speakers was 15% of the population.

During the 19th century a national awakening occurred in Finland. It was supported by the Russian central administration for practical reasons, as a security measure to weaken Swedish influence in Finland. This trend was reinforced by the general wave of nationalism in Europe in the mid-19th century. As a result, under the influence of the German idea of one national language, a strong movement arose that promoted the use of the Finnish language in education, research and administration.[Note 13] Many influential Swedish-speaking families learned Finnish, fennicized their names and changed their everyday language to Finnish, sometimes not a very easy task. This linguistic change had many similarities with the linguistic and cultural revival of 19th century Lithuania where many former Polish speakers expressed their affiliation with the Lithuanian nation by adopting Lithuanian as their spoken language. As the educated class in Finland was almost entirely Swedish-speaking, the first generation of the Finnish nationalists and Fennomans came predominantly from a Swedish-speaking background.

| Year | Percent |

|---|---|

| 1610 | 17.5% |

| 1749 | 16.3% |

| 1815 | 14.6% |

| 1880 | 14.3% |

| 1900 | 12.9% |

| 1920 | 11.0% |

| 1940 | 9.5% |

| 1950 | 8.6% |

| 1960 | 7.4% |

| 1980 | 6.3% |

| 1990 | 5.9% |

| 2000 | 5.6% |

| 2010 | 5.4% |

| 2020 | 5.2% |

The language issue was not primarily an issue of ethnicity, but an ideological and philosophical issue as to what language policy would best preserve Finland as a nation. This also explains why so many academically educated Swedish speakers changed to Finnish: it was motivated by ideology. Both parties had the same patriotic objectives, but their methods were completely the opposite. The language strife would continue up until World War II.

The majority of the population – both Swedish and Finnish speakers – were farmers, fishermen and other workers. The farmers lived mainly in unilingual areas, while the other workers lived in bilingual areas such as Helsinki. This co-existence gave birth to Helsinki slang – a Finnish slang with novel slang words of Finnish, local and common Swedish and Russian origin. Helsinki was primarily Swedish-speaking until the late 19th century, see further: Fennicization of Helsinki.

The Swedish nationality and quest for territorial recognition

The Finnish-speaking parties, under the lead of Senator E. N. Setälä who played a major role in the drafting the language act (1922) and the language paragraphs (1919) in the Finnish constitution, interpreted the language provisions so that they are not supposed to suggest the existence of two nationalities. According to this view Finland has two national languages but only one nationality. This view was never shared in the Swedish-speaking political circles and paved the way for a linguistic conflict. Contrary to the Finnish-speaking view the leaders of the Swedish nationality movement (Axel Lille and others) maintained that the Swedish population of Finland constituted a nationality of its own and the provisions of the constitution act were seen to support the view.[12] The Finnish-speaking political circles denoted the cultural rights of Finland-Swedes as minority rights. The Finland-Swedish political view emphasized the equality of the Swedish nationality next to the Finnish-speaking nationality and the fact the national languages of Finland were the languages of the respective nationalities of the country, not the languages of the state itself. The concept of minority, although de facto the case for Swedish speakers, was perceived as being against the spirit of the constitution. However, gradually after the Second World War, the concept of minority has been increasingly applied to Swedish speakers, even within the Finland-Swedish political discourse.

The Swedish nationality movement was effectively mobilized during the aftermath of Finnish independence and the civil war that shortly followed. The Swedish assembly of Finland was founded to protect the linguistic integrity of Swedish-speakers and seek fixed territorial guarantees for the Swedish language for those parts of the country where Swedish speakers made up the local majority.[38] The Finnish-speaking parties and leadership studiously avoided self-government for Swedish speakers in the Finnish mainland. Of the broader wishes of the Swedish-speaking political movement only cultural concessions—most notably administrative autonomy for Swedish schools and a Swedish diocese—were realized, which nevertheless were sufficient to prevent more thorough conflict between the ethno-linguistic groups.[Note 14]

Developments since the late 19th century

The urbanization and industrialization that began in the late 19th century increased the interaction between people speaking different languages with each other, especially in the bigger towns. Helsinki (Helsingfors in Swedish and predominantly used until the late 19th century), named after medieval settlers from the Swedish province of Hälsingland, still mainly Swedish-speaking in the beginning of the 19th century, attracted Finnish-speaking workers, civil servants and university students from other parts of Finland, as did other Swedish-speaking areas.[Note 15] As a result, the originally unilingual Swedish-speaking coastal regions in the province of Nyland were cut into two parts. There was a smaller migration in the opposite direction, and a few Swedish-speaking "islands" emerged in towns like Tampere, Oulu and Kotka.

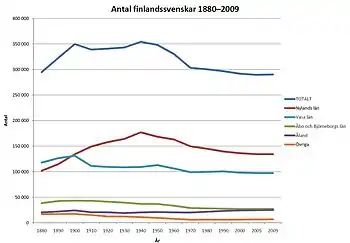

According to official statistics, Swedish speakers made up 12.9% of the total population of Finland of 2.6 million in 1900. By 1950 their proportion had fallen to 8.6% of a total of 4 million people, and by 1990 they formed 5.9% of the country's 5 million people. This sharp decline has since levelled off to more modest annual declines.

An important contribution to the decline of Swedish speakers in Finland during the second half of the 20th century was that many Swedish speakers emigrated to Sweden. An estimated 30–50% of all Finnish citizens who moved to Sweden were Swedish-speaking Finns. Reliable statistics are not available, as the Swedish authorities, as opposed to their Finnish counterpart, do not register languages. Another reason is that the natural increase of the Finnish-speakers has been somewhat faster than that of the Swedish-speakers until recent times, when the trend has reversed.

During most of the 20th century, marriages across language borders tended to result in children becoming Finnish speakers, and knowledge of Swedish declined. During the last decades the trend has been reversed: many bilingual families chose to register their children as Swedish speakers and put their children in Swedish schools. One motive is the language skills needed during their professional lives. Population statistics do not recognize bilingualism.

Historical relationship of the Swedish- and Finnish-speaking populations

The Finnish substrate toponyms (place names) within today's Swedish-speaking areas have been interpreted as indicative of earlier Finnish settlements in the area.[Note 16][Note 17] A toponymical analysis from e.g. the Turunmaa archipelago—today largely Swedish-speaking—suggests the existence of a large population of native Finnish speakers up until the early modern age.[Note 18] Whether the Finnish settlements prior to the arrival of the Swedes have been permanent or seasonal is debated. According to another toponymic study, some Finnish villages and farms on the south-western coast and the archipelago became Swedish-speaking by assimilation.[Note 19]

According to another view (e.g. Tarkiainen 2008) the two major areas of Swedish language speakers (Nyland and Ostrobothnia) were largely uninhabited at the time of the arrival of Swedes.[Note 20]

According to an interpretation based on the results of recent (2008) genome-wide SNP scans and on church records from the early modern period, Swedish-speaking peasantry has been overwhelmingly endogamous. Historian Tarkiainen (2008) presents that from the late Middle Ages onwards until relatively recent times, Swedish-speaking peasants tended to select their marriage partners from the same parish, often from the same village as themselves. This tends to be the rule among traditional peasant communities everywhere. As tightly-knit peasant communities tend to assimilate potential newcomers very quickly, this has meant that most marriages within the Swedish-speaking peasantry during this period were contracted with members of the same language group. During the time of early immigration by Swedes to the coastal regions (approximately between 1150 and 1350), the situation was different and according to a study from the 1970s (as referenced by Tarkiainen, 2008) the intermarriage rate between local Finns and Swedish newcomers was considerable. According to Tarkiainen, in the areas of initial Swedish immigration, the local Finns were assimilated into the Swedish-speaking population.[Note 21]

Culture, literature and folklore

Finland-Swedish folklore along the coast has been traditionally maritime-influenced. The folklore themes are typical in the Nordic context. Stories and tales involving the evil water-spirit are central. The origins of some of the tales have been German and French from which they have been adapted to the Nordic milieu. (Finland)-Swedish folklore has also had a significant impact on the folklore of Finnish speakers.[Note 22]

Finland-Swedish literature has a rich legacy. Under the lead of Edith Södergran, who also captivated audiences in English-speaking world, Gunnar Björling and Elmer Diktonius, the Finland-Swedish modernists of the early 20th century had a significant impact on the whole of Scandinavian modernism.

Tove Jansson is perhaps the most renowned example of Finland-Swedish prose. Her Moomin books have fascinated children and adults throughout the world.

On 6 November, Finnish Swedish Heritage Day, a general flag flying day, is celebrated in Finland; the day celebrates the Swedish-speaking population of Finland, their culture, and the bilinguality of Finland.[42]

Genetics

In a 2008 study a joint analysis was performed for the first time on Swedish and Finnish autosomal genotypes. Swedish-speakers from Ostrobothnia (reference population of the study representing 40% of all Swedish-speakers in Finland) did not differ significantly from the neighbouring, adjacent Finnish-speaking populations but formed a genetic cluster with the Swedes[Note 23] and also the amount of genetic admixture between the groups which have taken place historically. According to a 2008 Y-DNA study, a Swedish-speaking reference group from Larsmo, Ostrobothnia, differed significantly from the Finnish-speaking sub-populations in the country in terms of Y-STR variation. This study however was comparing one small Swedish-speaking municipality of 4652 inhabitants to Finnish-speaking provinces and only tells about the origin of two different Y-DNA haplotypes.[Note 24]

Identity

According to a sociological study published in 1981, the Swedish-speaking Finns meet the four major criteria for a separate ethnic group: self-identification of ethnicity, language, social structure, and ancestry.[Note 25] However, not all Swedish-speaking Finns are willing to self-identify as representatives of a distinct ethnicity. The major political organisation representing the Swedish-speakers in Finland, the Swedish People's Party, has defined the Swedish-speaking Finns as a people who express Finnish identity in the Swedish language. The issue is debated: an opposite view is still that the Swedish-speaking Finns are a sub-group of the ethnic Swedes, östsvenskar or "East Swedes".

Despite these varying viewpoints, the Swedish-speaking population in Finland in general have their own identity distinct from that of the majority, and they wish to be recognized as such.[Note 26] In speaking Swedish, Swedish-speaking Finns predominantly use the Swedish word finländare (approximately translatable as Finlanders) when referring to all Finnish nationals. The purpose is to use a term that includes both themselves and Finnish-speaking Finns because the Swedish word finnar, in Finland-Swedish usage, implies a Finnish-speaking Finn. In Sweden, this distinction between finländare and finnar is not widely understood and often not made.

In literature regarding to international law and minority rights, a view that the Swedish-speakers in Finland not only constitute an ethnic minority but a distinct nationality has also been presented.[Note 27]

Marriages between Swedish- and Finnish-speakers are nowadays very common. According to a study commissioned by the Swedish Assembly of Finland in 2005,[47] 48.5% of all families with children where at least one of the parents was Swedish-speaking were bilingual in the sense of one parent being Swedish- and the other Finnish-speaking (only families living in those municipalities where Swedish was at least a co-official language were included in this study). 67.7% of the children from these bilingual families were registered as Swedish-speaking. The proportion of those who attended schools where Swedish was the language of instruction was even higher. The Finnish authorities classify a person as a Swedish- or Finnish-speaker based only upon that person's (or parent's) own choice, which can be changed at any time. It is only possible to be registered either as Swedish- or Finnish-speaking, not both as in Canada, for example. It is significantly more common nowadays than it used to be for children from bilingual families to be registered as Swedish-speaking.

Historical predominance of the Swedish language among the gentry

Areas of modern-day Finland were integrated into the Swedish realm in the 13th century, at a time when that realm was still in the process of being formed. At the time of Late Middle Ages, Latin was still the language of instruction from the secondary school upwards and in use among the educated class and priests. As Finland was part of Sweden proper for 550 years, Swedish was the language of the nobility, administration and education. Hence the two highest estates of the realm, i.e. nobles and priests, had Swedish as their language. In the two minor estates, burghers and peasants, Swedish also held sway, but in a more varying degree depending on regional differences.

Most noble families of the medieval period arrived directly from Sweden.[Note 28][Note 29] A significant minority of the nobility had foreign origins (predominantly German), but their descendants normally adopted Swedish as their first language.

The clergy in the earlier part the formation of the Lutheran Church (in its High Church form) was constituted most often of the wealthier strata of the peasantry with the closely linked medieval Finnish nobility and the rising burgher class in the expanding cities. The Church required fluency in Finnish from clergymen serving in predominantly or totally Finnish-speaking parishes (most of the country); consequently clerical families tended to maintain a high degree of functional bilingualism. Clerical families in the whole seem to have been more fluent in Finnish than the burghers as whole. In the Middle Ages, commerce in the Swedish realm, including Finland, was dominated by German merchants who immigrated in large numbers to the cities and towns of Sweden and Finland. As a result, the wealthier burghers in Sweden (and in cities as Turku (Åbo) and Vyborg (Viborg)) during the late Middle Ages tended to be of German origin. In the 19th century, a new wave of immigration came from German-speaking countries predominantly connected to commercial activities, which has formed a notable part of the grand bourgeoisie in Finland to this day .

After the Finnish war, Sweden lost Finland to Russia. During the period of Russian sovereignty (1809–1917) the Finnish language was promoted by the Russian authorities as a way to sever the cultural and emotional ties with Sweden and to counter the threat of a reunion with Sweden. Consequently, the Finnish language began to replace Swedish in the administrative and cultural sphere during the later part of the 19th century.

The rise of the Finnish language to an increasingly prevalent position in society was, at the outset, mainly a construct of eager promoters of the Finnish language from the higher strata of society, mainly with Swedish-speaking family backgrounds. A later development, especially at the beginning of the 20th century, was the adoption or translation or modification of Swedish surnames into Finnish (fennicization). This was generally done throughout the entire society. In upper-class families it was predominantly in cadet branches of families that the name translations took place.[49]

Opposition to the Swedish language was partly based around historical prejudices and conflicts that had sprung up during the 19th century. The intensified language strife and the aspiration to raise the Finnish language and Finnic culture from peasant status to the position of a national language and a national culture gave rise to negative portrayals of Swedish speakers as foreign oppressors of the peaceful Finnish-speaking peasant.

Even though the proportional distribution of Swedish-speakers among different social strata closely reflects that of the general population, there is still a lingering conception of Swedish as a language of the historical upper class culture of Finland. This is reinforced by the fact that Swedish-speakers are statistically overrepresented among "old money" families as well as within the Finnish nobility consisting of about 6000 persons, of which about two thirds are Swedish-speakers. Still the majority of the Swedish-speaking Finns have traditionally been farmers and fishermen from the Finnish coastal municipalities and archipelago.

Bilingualism

Finland is a bilingual country according to its constitution. This means that members of the Swedish language minority have the right to communicate with the state authorities in their mother tongue.

On the municipal level, this right is legally restricted to municipalities with a certain minimum of speakers of the minority language. All Finnish communities and towns are classified as either monolingual or bilingual. When the proportion of the minority language increases to 8% (or 3000), then the municipality is defined as bilingual, and when it falls below 6%, the municipality becomes monolingual. In bilingual municipalities, all civil servants must have satisfactory language skill in either Finnish or Swedish (in addition to native-level skill in the other language). Both languages can be used in all communications with the civil servants in such a town. Public signs (such as street and traffic signs, as illustrated) are in both languages in bilingual towns and municipalities the name in majority language being on the top.

The Swedish-speaking areas in Finnish Mainland do not have fixed territorial protection, unlike the languages of several national minorities in Central Europe such as German in Belgium and North Italy. This has caused a heated debate among Swedish-speaking Finns. The current language act of Finland has been criticized as inadequate instrument to protect the linguistic rights of Swedish-speaking Finns in practice.[Note 30][Note 31] The criticism was partly legitimized by the report (2008) conducted by Finnish government which showed severe problems in the practical implementation of the language act.[Note 32][53] The recent administrative reforms in Finland have caused harsh criticism in the Swedish-speaking media and created fear over the survival of Swedish as an administrative language in Finland.[Note 33] A special status in the form partial self-determination and fixed protection for Swedish language in Swedish-speaking municipalities have been proposed in Finland's Swedish-speaking media.[Note 34]

Following an educational reform in the 1970s, both Swedish and Finnish became compulsory school subjects. The school subjects are not called Finnish or Swedish; the primary language in which lessons are taught depends upon the pupil's mother tongue. This language of instruction is officially and in general practice called the mother tongue (äidinkieli in Finnish, modersmål in Swedish). The secondary language, as a school subject, is called the other domestic language (toinen kotimainen kieli in Finnish, andra inhemska språket in Swedish). Lessons in the "other domestic language" usually start in the third, fifth or seventh form of comprehensive school and are a part of the curriculum in all secondary education. In polytechnics and universities, all students are required to pass an examination in the "other domestic language" on a level that enables them to be employed as civil servants in bilingual offices and communities. The actual linguistic abilities of those who have passed the various examinations however vary considerably.

Being a small minority usually leads to functional bilingualism. Swedish-speaking Finns are more fluent in Finnish than Finnish-speakers are in Swedish due to the practical matter of living in a predominantly Finnish-speaking country. In big cities with a significant Swedish-speaking population such as Helsinki and Turku, most of them are fluent in both Swedish and Finnish. Although in some municipalities Swedish is the only official language, Finnish is the dominant language in most towns and at most employers in Finland. In areas with a Finnish-speaking majority, Finnish is most often used when interacting with strangers and known Finnish speakers. However, 50% of all Swedish speakers live in areas in which Swedish is the majority language and in which they can use Swedish in all or most contexts (see demographics below).

Demographics

Of the Swedish-speaking population of Finland,

- 44% live in officially bilingual towns and municipalities where Finnish dominates,

- 41% live in officially bilingual towns and municipalities where Swedish dominates,

- 9% live in Åland, of whose population about 90% was Swedish-speaking in 2010,[56]

- 6% live in officially monolingual Finnish-speaking towns and municipalities.

Swedish-speaking immigrants

There is a small community of Swedish-speaking immigrants in Finland. Many of them come from Sweden, or have resided there (about 8,500 Swedish citizens live in Finland[57] and around 30,000 residents in Finland were born in Sweden[58]), while others have opted for Swedish because it is the main language in the city in which they live, or because their partners are Swedish-speaking.[59] About one quarter of immigrants in the Helsinki area would choose to integrate in Swedish if they had the option.[60] According to a report by Finland's Swedish think tank, Magma, there is a widespread perception among immigrants that they are more easily integrated in the Swedish-speaking community than in the majority society. However, some immigrants also question whether they ever will be fully accepted as Finland Swedes.[61] Swedish-speaking immigrants also have their own association, Ifisk,[62] and in the capital region there is a publicly financed project named Delaktig aimed at facilitating integration of immigrants who know or wish to learn Swedish.[63] Most if not all immigrants also wish to be fluent in Finnish due to the fact that it is the dominant language in Finnish society.

Diaspora

Swedish speakers have migrated to many parts of the world. One study has shown they are more likely to emigrate than the rest of the Finnish population.[64] It is estimated that between the early 1870s and late 1920s, approximately 70,000 Swedish-speaking Finns emigrated to North America. In Minnesota, a number settled on the Iron Range, in Minneapolis-Saint Paul, and in the northeastern part of the state including Duluth and along the North Shore of Lake Superior. Larsmont, Minnesota, a town named after Larsmo, Finland, was founded by Swedish-speaking Finns in the early 1900s.[65][66]

For a number of reasons, including geographical and linguistic reasons, Sweden has traditionally been the number one destination for Swedish-speaking emigrants. In one study covering the period 2000–2015, over half of the 26,000 Swedish-speaking Finns who had moved abroad moved to Sweden.[67] There are about 200,000 Swedish-speaking Finns living in Sweden (Sverigefinlandssvenskar), according to Finnish broadcaster Yle. Due to noticeable differences between Finland Swedish and Swedish as spoken in Sweden, Swedish-speaking Finns have been mistaken for non-native speakers and have been required to take language courses.[68][69] Groups, particularly Finlandssvenskarnas riksförbund i Sverige (Fris), an interest group, have campaigned for decades in Sweden for recognition as an official national minority group, in addition to the five existing recognized groups: Sámi, Jews, Romani, Sweden Finns, and Tornedalians. The issue has been debated in the Swedish Parliament (Riksdag) several times, with the 2017 attempt failing due to the ethnic group not being established in the country prior to 1900.[70][71]

The Swedish-Finn Historical Society is a Washington state, USA-based association which aims to preserve the ethnic group's emigration history.[65]

From 1990 to 2021, a total of 50,034 Swedish-speaking Finns have emigrated abroad. 76.5% moved to other Nordic countries. The most popular destinations were;

Sweden 32,867 (65.7%)

Sweden 32,867 (65.7%) Norway 3,437 (6.9%)

Norway 3,437 (6.9%) Denmark 1,872 (3.7%)

Denmark 1,872 (3.7%) United Kingdom 1,720 (3.4%)

United Kingdom 1,720 (3.4%) United States 1,446 (2.9%)

United States 1,446 (2.9%) Germany 1,352 (2.7%)

Germany 1,352 (2.7%) Spain 932 (1.9%)

Spain 932 (1.9%) Netherlands 495 (1.0%)

Netherlands 495 (1.0%) Iceland 115 (0.2%)

Iceland 115 (0.2%)

In 2021, 1,432 Finland-Swedes moved abroad, which was the lowest amount since 1996. Emigration peaked during 2015-2018, when nearly 2,000 emigrated annually. They made up 20.1% of Finnish emigrants in 2021. Net migration of Swedish-speakers from Sweden was 256 in 2021.[72]

Notable Swedish-speakers from Finland

- Lars Ahlfors, mathematician, Fields Medal winner

- Antti Ahlström, industrialist and founder of the Ahlstrom Corporation

- Gustaf Mauritz Armfelt, courtier and diplomat, and in Finland, he is considered one of the great Finnish statesmen

- Niklas Bäckström, ice hockey goaltender for the Minnesota Wild of the NHL

- Hjalmar von Bonsdorff, Admiral, first governor of Åland and politician

- Jörn Donner, writer, film director, actor, producer and politician

- Albert Edelfelt, painter

- Johan Albrecht Ehrenström, architect and chairman of the committee in charge of rebuilding the city of Helsinki

- Johan Casimir Ehrnrooth, soldier in the service of Imperial Russia, who also acted as Prime Minister of Bulgaria

- Arvid Adolf Etholén, Naval officer employed by the Russian-American Company[73]

- Karl-August Fagerholm, three times Prime Minister of Finland

- Kaj Franck, leading figure in Finnish design

- Akseli Gallen-Kallela, painter best known for his illustrations of the Kalevala (the Finnish national epic)

- Ragnar Granit, scientist, Nobel laureate in physiology or medicine in 1967

- Marcus Grönholm, rally driver, two-time world champion

- Bengt Holmström, Nobel laureate in economic sciences

- Fredrik Idestam, mining engineer and businessman, best known as a founder of Nokia

- Tove Jansson, painter, illustrator, writer, creator of Moomin characters

- Eero Järnefelt, realist painter

- Pernilla Karlsson, singer

- Linda Lampenius, classical violinist

- Kevin Lankinen, ice hockey goaltender for the Chicago Blackhawks of the NHL

- Mathias Lillmåns, vocalist of folk/black metal band Finntroll

- Magnus Lindberg, composer

- Isak Elliot Lundén, singer-songwriter

- Gustaf Mannerheim, Marshal and President of Finland, commander-in-chief during the Winter War

- Gustaf Nordenskiöld, explorer of the cliff dwellings of Mesa Verde, Colorado; son of Adolf Erik Nordenskiöld

- Adolf Erik Nordenskiöld, Arctic explorer, first to conquer the Northeast passage and circumnavigate Eurasia; father of Gustaf Nordenskiöld

- Paradise Oskar, singer-songwriter (real name: Axel Ehnström)

- Kebu, keyboard player, songwriter, producer (real name: Sebastian Teir)

- Emil von Qvanten, poet and politician

- Johan Ludvig Runeberg, romantic writer and Finland's national poet

- Helene Schjerfbeck, painter

- André Linman, musician

- Jean Sibelius, classical composer

- Krista Siegfrids, pop musician

- Janina Orlov, translator

- Johan Vilhelm Snellman, influential Fennoman philosopher and Finnish statesman

- Lars Sonck, architect

- Kaarlo Juho Ståhlberg, 1st President of Finland

- Pehr Evind Svinhufvud, 3rd President of Finland

- Edith Södergran, modernist poet

- Eric Tigerstedt, Finnish inventor at the beginning of the 20th century, often referred to as the "Thomas Edison of Finland"

- Zacharias Topelius, journalist, historian and author

- Linus Torvalds, software engineer, creator of the Linux kernel

- Michael Widenius, software programmer and the main author of the original version of the open source MySQL relational database management system

- Rudolf Walden, industrialist and general

- Martin Wegelius, composer, musicologist, and founder of the Sibelius Academy

- Georg Henrik von Wright, philosopher

See also

- Demographics of Finland

- Svenskfinland

- Finland Swedish – the language spoken by the Finland Swedes

- Finnish people – the ethnic groups of Finns

- Swedish people – the ethnic group of Swedes

- Sweden Finns – people of Finnish descent in Sweden

- Diocese of Borgå

- Swedish unit of the Finnish Broadcasting Company

- Swedish Assembly of Finland

- List of Swedish-speaking Finns

- List of Swedish-speaking and bilingual municipalities of Finland

- Svecoman movement

- Fennoman movement

- Fennicization

- Finlandssvensk samling

- Yle FSR

Notes

- Swedish-speaking Finns,[5] Finland-Swedes, Finland Swedes, Finnish Swedes, or Swedes of Finland. The term Swedo-Finnish[6][7] (Swedish: finlandssvensk; Finnish: suomenruotsalainen) can be used as an attribute.

- In a 2005 survey, 82% of the Swedish-speaking respondents felt the following best described their identity among the different choices provided: "Both belonging to a separate culture and being a Finn like others." (Swedish: Både att höra till en egen kultur, men också att vara en finländare bland alla andra. Finnish: Kuulumista omaan kulttuuriin, mutta myös suomalaisena olemista muiden joukossa.)[8]

- "At the same time the new generations are still proud of their special characteristics and of their culture as part of the Finnish people." ("Samanaikaisesti uudet sukupolvet ovat kuitenkin edelleen ylpeitä erityispiirteistään ja kulttuuristaan osana Suomen kansaa.")[9]

- "... Finland has a Swedish-speaking minority that meets the four major criteria of ethnicity, i.e. self-identification of ethnicity, language, social structure and ancestry[10][11]

- "In Finland this question (Swedish nationality) has been subjected to much discussion. The Finnish majority tries to deny the existence of a Swedish nationality. An example of this is the fact that the statutes always use the concept 'Swedish-speaking' instead of 'Swedish'". "The concept of nation has a different significance as meaning of a population group or an ethnic community, irrespectively of its organization. For instance, the Swedes of Finland, with their distinctive language and culture form a nationality which under the Finnish constitution shall enjoy equal rights with the Finnish nationality". "It is not correct to call a nationality a linguistic group or minority if it has developed a culture of its own. If there is not only a community of language but also of other characteristics such as folklore, poetry and literature, folk music, savvy, behavior, etc."[12]

- "Less well known internationally is the 6 percent minority of ethnic Swedes in Finland. While we never hear of 'Sami-speaking Norwegians', 'Hebrew-speaking Palestinians' etc., one often stumbles on the term 'Swedish-speaking Finns' to denote a certain group of ethnic Swedes. This is a way of denying the group their ethnic identity. Admittedly, something similar is practised in Turkey, where the Kurds are called 'Mountain Turks' in official quarters"[19]

- "To define a person as Swedish-speaking says nothing about whether he or she has Finland-Swedish identity". "McRae distinguishes a gap in Finland between the formal 'linguistic peace' and the practical 'linguistic instability' which put the Finland-Swedes in a 'sociological, psychological and political' minority position. Consistent with this, Allardt (2000:35) claims that the most serious contemporary problem for the Finland Swedes is the members of the group themselves: their 'submissiveness' and willingness to 'conceal their Finland-Swedishness' in the face of the majority. Furthermore, the Finland-Swedes' relations to Sweden are considered a sensitive issue in Finland. Höckerstedt (2000:8–9) argues that an emphasis on the 'Swedish' part of the Finland-Swedish identity is 'taboo-laden' and regarded as unpatriotic."[20]

- " Den svenska kolonisationen av Finland och områdets införlivande med Sverige hör till detta sammanhang. Sveriges jord räckte inte under denna expansiva tid till för befolkningen i Sverige. Skaror av svenskar sökte sig nytt land i Finlands kustområden, och fann där nya boplatser. För första gången smalt de inte samman med den infödda befolkningen, eftersom det svenska storsamhället verkade för svenskarnas nationella och språkliga fortbestånd i landet".[22]

- "Den svenska kolonisationen av västra Nyland skedde etappvis. De första invandrarna torde ha kommit till Egentliga Finland under missionstiden, när ett antal svenskar slog sig ner i Karisnejdens kustland, där vissa åldriga ortnamn med början på rots (t.ex. Rådsböle) vittnar om deras bosättning. Dessa namn syftar på Roslagen. Den andra vågen, som sökte sig till central bygden vid Pojovikens vattensystem, kom troligen under andra korståget på 1200-talet. Den förde sig inflyttare fråm flera håll in Sverige och ägde rum i skuggan av en militäroperation mot Tavastland."[22]

- "Den svenska kolonisationen hade en uppenbar masskaraktär och var styrd uppifrån, främst av kronan, vilket framgår av att hemmanen var kronohemman. Folk kom inte längre i allmogefarkoster utan skeppades över på större fraktfartyg, och tydligen från alla håll inom Sveariket – Åtminstone från Uppland, Småland, Gästrikland och Hälsingland.[22]

- "Från Sideby i söder till Karleby i norr, en sträcka på omkring 300 kilometerm går en obruten kedja av svenska hemman, byar och samhällen och detta kustland sträcker sig som en circa 30 kilometer bred zon inåt landet". "Österbottens bosättningshistoria har sin parallel i kolonisationen av Norrlandskusten under samma epok".[22]

- "Many scholars were drawn into this debate, and a later writer notes "a correlation between the scholar's mother-tongue and his view on the age and continuity of Scandinavian settlements of the country" (Hämäläinen, 1966), whereas Finnish writers tended to deny or minimize the presence of Swedish speakers before the historically documented expeditions of the twelfth century, Swedish-speaking scholars have found archeological and philological evidence for a continuous Swedish or Germanic presence in Finland from pre-historic times."[27]

- "Den nationella rörelsen i Finland, fennomanin, som utgick från Friedrich Hegels tankar, strävade efter att skapa en enad finsk nation för att stärka Finlands ställning. Nationens gränser skulle sammanfalla med dess folks gränser, och alltså också dess språks gränser. Målet var bland annat en förfinskning av Finland"[35]

- "For the mainland provinces, the Finnish-speaking parties and leadership studiously avoided self-government for Swedish speakers but instead offered cultural concessions—most notably administrative autonomy for Swedish schools and a Swedish diocese—that were sufficient to satisfy moderate Swedish-speakers and to discourage activists from striving for more. As our previous analysis has suggested at several points, a retrospective view of subsequent language development strongly suggest that the centre-oriented Swedish-speaking leadership made a flawed decision in accepting this settlement, though whether more could have been achieved at that point by harder bargaining is difficult to assess".

- "In towns, however, the linguistic balance started to change in the 20th century. The most significant changes have taken place in the past few decades, when new native speakers of Finnish moved into the towns in large numbers. The capital region of Helsinki has been affected the most by this development. Gradually, what were formerly profoundly Swedish-speaking parishes in the countryside have become densely populated towns with a majority of Finnish-speaking inhabitants"[39]

- "However, this does not mean that Swedes would have inhabited only settled areas that were completely unpopulated. Indeed, it is probable that no such areas were available. We can assume that the rest of the coastal area was inhabited by Finns at the time when the Swedish settlers arrived in the country. Our assumption is based on place names: the Swedish place names on the coast include numerous Finnish substrate names—incontrovertible proof of early Finnish settlement."[39]

- "Another indication of older Finnish settlement is evidenced by the fact that native speakers of Finnish named so many different types of places in the area that the substrate nomenclature seems to consist of names referring to village settlement rather than to names of natural features."[39]

- "This seems to support our conception that there was a large population of native speakers of Finnish in the archipelago and that it remained Finnish-speaking for a longer period than was previously believed."[39]

- "The Swedish colonization primarily focused on coastal areas and the archipelago, but eventually expanded as farms and villages that had previously been Finnish became Swedish-speaking".[40]

- "Östra Nyland var vid 1200-talets mitt ett ännu jungfruligt område än västra Nyland. Landskapet hade karaktären av en ofantlig, nästan obebudd ödemark med en havskust som endast sporadiskt, vid tiden för strömnings och laxfiske, besöktest av finnar från Tavastland samnt troligen även av samer"[22] "Efter kolonisationen fick kusten nästan helsvensk bosättning; bynamnen är till 70–100% av svensk ursprung. Enligt beräkningar av Saulo Kepsu (Kepsu, Saulo, Uuteen Maahan, Helsinki 2005) är bynamnen mest svenskdominerade i väster (Pojo-Karistrakten) och i öster (Borgå-Pernå) med en svacka i mellersta Nyland)"[22] "Finska ortnamn är ovanligt få inom Sibbo, vilket tyder på att området var praktiskt taget folktomt när svenskarna kom"[41]

- "Från senare tid vet man genom släktforskning att den svenska kustbefolkningen har varit starkt endogam i sin fortplantning, på så sätt att äkta makar kom från familjer som levde nära varandra, ofta i samma by. Så var fallet överallt bland allmogen, även den finska, och man gissar att antalet blandäktenskap mellan kontrahenter från olika språkgrupper under den tid som kyrkoböcker har förts har hållit sig stadigt under en procentenhet. När befolkningstalet har uppnått en viss storlek och näringslivet stabiliserats är det lätt att finna sin äktenskapliga partner på nära håll. Invandringstiden tycks däremot ha varit en tid då ett stort antal blandäktenskap ingicks mellan svenskar och finnar i de kustnära bygderna. Förhållandena måste ha varit mycket rörliga och den manliga övervikten bland inflyttarna stor. Forskarna har räknat ut att om blandningsprocenten var ca 20 procent – d.v.s. om bara vart femte äktenskap var ett blandäktenskap – skulle det ha tagit fyra till fem generationer innan de gemensamma dragen utgjorde 60 procent av de två gruppernas totala genuppsättning. Om blandningsprocenten däremot var endast 10 procent – bara vart tionde äktenskap var svensk-finskt – skulle det ha tagit åtta till nio generationer att uppnå samma resultat. Med tanke på att kolonisationstiden varade ungefär från 1150 till 1300, eller kanske 1350, och generationerna var kortare än i dag, är båda alternativen möjliga. Mest troligt är det att blandäktenskap var mycket vanliga i kolonisationens tidigaste fas. Det stora upptagandet av finska ortnamn tyder på detta, liksom också den finskpåverkade satsintonation som de finlandssvenska dialekterna uppvisar. Man får sålunda sannolikt räkna med en hög andel finnar, inte bara in särskilda byar eller "finnbölen", utan också i de svenska bosättningarna som familjemedlemmar och tjänstefolk. Språksituationen kan sålunda under den tidiga kolonisationsfasen och tiderna därefter betraktas som blandspråkig. Först så småningom smälter det finska inslaget ihop med det svenska och det exogama samhället sluter sig och blir endogamt".[22]

- "En del av stoffet har har gått vidare till finnarna och utgör ett element i västra Finlands folklore. Särskilt när det gäller folksångerna har finlandssvenskarna haft en stor betydelse för den yngre finska folkpoesin".[22]

- "Clear East-West duality was observed when the Finnish individuals were clustering using Geneland. Individuals from the Swedish-speaking part of Ostrobotnia clustered with Sweden when a joint analysis was performed on Swedish and Finnish autosomal genotypes".[43]

- "The subpopulation LMO (Larsmo, Swedish-speaking) differed significantly from all the other populations". "The geographical substructure among the Finnish males was notable when measured with the ΦST values, reaching values as high as ΦST=0.227 in the Yfiler data. This is rather extreme, given that, e.g., subpopulations Larsmo and Kymi are separated by mere 400 km, with no apparent physical dispersal barriers between them".[44]

- Finland has generally been regarded as an example of a monocultural and egalitarian society. However, Finland has a Swedish-speaking minority that meets the four major criteria of ethnicity, i.e. self-identification of ethnicity, language, social structure and ancestry.[45]

- "The identity of the Swedish[-speaking] minority is however clearly Finnish (Allardt 1997:110). But their identity is twofold: They are both Finland Swedes and Finns (Ivars 1987)." (Die Identität der schwedischen Minderheit ist jedoch eindeutig finnisch (Allardt 1997:110). Ihre Identität ist aber doppelt: sie sind sowohl Finnlandschweden als auch Finnen (Ivars 1987).)[46]

- "In Finland this question (Swedish nationality) has been subjected to much discussion. The Finnish majority tries to deny the existence of a Swedish nationality. An example of this is the fact that the statutes always use the concept "Swedish-speaking" instead of Swedish", "The wording of the Finnish Constitution (Art. 14.1): "Finnish and Swedish shall be the national languages of the republic" has been interpreted by linguist and constitution-writing politician E.N. Setälä and others as meaning that these languages are the State languages of Finland instead of the languages of the both nationalities of Finland", "It is not correct to call a nationality a linguistic group or minority, if it has developed culture of its own. If there is not only a community of language, but also of other characteristics such as folklore, poetry and literature, folk music, theater, behavior, etc."[12]

- "Nyland has always been characterised as an area of medieval colonisation conducted by the Swedes. Previously this colonisation has been seen as an immigration of independents peasants. As a new result a significant noble impact has been verified both in the colonisation activity itself and the establishing of parish churches as well".[48]

- "Frälseståndets ursprung var till två tredjedel svenskt, till en tredjedel tyskt. Någon social rörelse som skulle ha fört kristnade finnar uppåt till dessa poster fanns inte, då jordegendomen inte var ett vilkor för en ledande ställning inom förvaltning, rättskipning och skatteadministration".[22]

- "One factor for instability is that Finland's language legislation, unlike that of Belgium or Switzerland, is based on flexible rather than fixed linguistic territoriality, except in the Åland islands, where Swedish enjoys a permanently protected special status"[50]

- "Där Ahlberg anser att det är statens plikt och skyldighet att implementera vår finländska, teoretiska tvåspråkighet också i praktiken, bland annat via olika specialarrangemang i olika regioner, anser Wideroos att det lurar en risk i att lyfta ut speciella regioner ur sitt nationella och finlandssvenska sammanhang"[51]

- "Språklagen från 2004 tillämpas inte ordentligt, visar regeringen i en redogörelse. Myndigheterna uppvisar fortfarande stora brister i användningen av svenska"[52]

- "Svenska riksdagsgruppens ordförande Ulla-Maj Wideroos (SFP) säger att det finns en dold politisk agenda i Finland med målet att försvaga det finlandssvenska.Wideroos sade i Slaget efter tolv i Radio Vega i dag att regeringens förvaltningsreformer enbart har som mål att slå sönder svenskspråkiga strukturer".[54]

- "Den österbottniska kustregionen borde få en specialstatus"[55]

References

- Project, Joshua. "Finland Swedes in Finland". joshuaproject.net. Retrieved 16 October 2021.

- "Appendix table 1. Population according to language 1980–2021". Statistics Finland. 31 March 2022. Retrieved 5 August 2022.

- "Encyklopedi om invandring, integration och rasism: Finlandssvenskar". Archived from the original on 27 January 2012. Retrieved 16 February 2010.

- "Sweden – Joshua Project". joshuaproject.net.

- "What is a dialect?". Institute for the Languages of Finland. Kotus. Archived from the original on 22 February 2015. Retrieved 31 October 2014.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - Kenneth Douglas McRae (1997). Conflict and Compromise in Multilingual Societies: Finland, Volume 3.

- James. E. Jacob. and. William. R. Beer (eds.) (1985). Language Policy and National Unity.

{{cite book}}:|author=has generic name (help) - See (Swedish)(Finnish)"Folktingets undersökning om finlandssvenskarnas identitet – Identitet och framtid", Folktinget, 2005.

- Folktinget: Ruotsinkielisenä Suomessa. Helsinki 2012, p. 2.

- Allardt and Starck, 1981.

- Bhopal, 1997.

- Tore Modeen, The cultural rights of the Swedish ethnic group in Finland (Europa Ethnica, 3–4 1999, p. 56).

- "Population 31.12. by Region, Language, Age, Sex, Year and Information". Tilastokeskuksen PxWeb-tietokannat. Retrieved 16 June 2022.

- "YLE Internytt: Tvåspråkigheten på frammarsch". Yle (in Swedish).

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - "Svenska Finlands folkting: Finlandssvenskarna 2005 – en statistik rapport" (PDF). folktinget.fi (in Swedish). Archived from the original (PDF) on 28 September 2007. Retrieved 22 September 2007.

- Holm, Carina (2 October 2010). "Fler finlandssvenskar". Åbo Underrättelser (in Swedish). Archived from the original on 31 October 2014. Retrieved 6 October 2012.

- "Kysymykset: kuinka suuri osa suomenruotsalaisista on kaksikielisiä, siis niin että molemmat..." [what percentage of Finnish-Swedes are bilingual, meaning that both...]. Helsinki City Library (in Finnish). Archived from the original on 9 November 2013.

- See, Finland-Swedish Think Tank Magma and Finland-Swedish Association.

- "carlonordling.se". www.carlonordling.se.

- Hedberg, C. 2004. The Finland-Swedish wheel of migration. Identity, networks and integration 1976–2000. Geographiska regionstudier 61.87pp.Uppsala. ISBN 91-506-1788-5.

- Roinila, Mika (2012). Finland-Swedes in Michigan. MSU Press. p. 21. ISBN 978-1-60917-325-8.

- Tarkiainen, Kari (2008). Sveriges Österland: från forntiden till Gustav Vasa. Finlands svenska historia. Vol. 1. Svenska litteratursällskapet i Finland. ISBN 9789515831552.

- "Main outlines of Finnish history". thisisFINLAND (Finnish Ministry for Foreign Affairs). 9 January 2014. Retrieved 16 June 2022.

- Ainiala, Terhi; Saarelma, Minna; Sjöblom, Paula (2008). Nimistöntutkimuksen perusteet (in Finnish). Helsinki: Finnish Literature Society. p. 68. ISBN 978-951-746-992-0.

- Kiviniemi, Eero (1980). "Nimistö Suomen esihistorian tutkimuksen aineistona" (PDF). kotikielenseura.fi (in Finnish). Retrieved 16 June 2022.

- McRae, 1993.

- McRae, 1993, Conflict and Compromise in Multilingual Society, case Finland.

- Huldén, Lars; Martola, Nina (2001). Finlandssvenska bebyggelsenamn: namn på landskap, kommuner, byar i Finland av svenskt ursprung eller med särskild svensk form (in Swedish). Helsinki: Society of Swedish Literature in Finland. ISBN 9789515830715. OCLC 48690289.

- Orrman, Elias (1993). "Where source criticism fails" (PDF). Fennoscandia Archaeologica. X. Archived (PDF) from the original on 11 July 2020. Retrieved 16 June 2022.

- Wickholm, Anna (2003). "Pörnullbacken – ett brandgravfält eller brandgropgravar?". Muinaistutkija (in Swedish) (4).

- Meinander, C. F. (1983). "Om svenskarnes inflyttningar till Finland". Historisk Tidskrift för Finland (in Swedish). 3.

- Thors, Carl-Eric (1953). Studier över finlandssvenska ortnamnstyper (in Swedish). Helsinki: Svenska litteratursällskapet i Finland. OCLC 470054426.

- Ahlbäck, Olav (1954). "Den finlandssvenska bosättningens älder och ursprung". Finsk Tidskrift (in Swedish).

- Haggrén, Georg; Halinen, Petri; Lavento, Mika; Raninen, Sami; Wessman, Anna (2015). Muinaisuutemme jäljet (in Finnish). Helsinki: Gaudeamus. p. 340. ISBN 9789524953634.

- "Tavaststjerna i provinsialismernas snårskog.Det sverigesvenska förlagsargumentet i finlandssvensk språkvård Av CHARLOTTA AF HÄLLSTRÖM-REIJONEN, 2007" (PDF).

- Jungner, Anna. "Swedish in Finland". finland.fi. Archived from the original on 9 October 2004. Retrieved 17 June 2022.

- "Population and Society". Statistics Finland. Retrieved 17 June 2022.

- Nikander, Gabriel; von Born, Ernst (1921). Den svenska nationaliteten i Finland (in Swedish). Helsinki: Holger Schildts Förlagsaktiebolag. OCLC 185183111.

- Borrowing of Place Names in the Uralian Languages, edited by Ritva Liisa Pitkänen and Janne Saarikivi.

- A study by Lars Huldén, Professor of Scandinavian Philology (2001), referred in the doctoral dissertation by Felicia Markus Living on the Other Shore. Stockholm University 2004.

- Christer Kuvaja & Arja Rantanen, Sibbo sockens historia fram till år 1868, 1998.

- "Folktinget". folktinget.fi. 3 July 2005. Archived from the original on 3 July 2005. Retrieved 17 June 2022.

- Population Genetic Association and Zygosity testing on preamplified Dna. 2008. Ulf Hannelius.

- Jukka U. Palo et al. 2008. The effect of number of loci on geographical structuring and forensic applicability of Y-STR data in Finland. Int J Legal Med (2008)122:449–456.

- Allardt and Starck, 1981; Bhopal, 1997). Markku T. Hyyppä and Juhani Mäki: Social participation and health in a community rich in stock of social capital

- Saari, Mirja: Schwedisch als die zweite Nationalsprache Finnlands . Retrieved 10 December 2006.

- "Finlandssvenskarna 2005 — en statistisk rapport" (PDF). folktinget.fi (in Swedish). Archived from the original (PDF) on 28 September 2007. Retrieved 22 September 2007.

- Haggren & Jansson, 2005. New light on the colonisation of Nyland

- See List of Finnish noble families.

- Finland: Marginal Case of Bicommunalism?, Kenneth D. McRae, 1988.

- "Mångfaldspolitik säkrar mervärdet av tvåspråkigheten - Vasabladet". Archived from the original on 18 July 2011. Retrieved 2 September 2009.

- "http://svenska.yle.fi/nyheter/sok.phpid=154463&lookfor=&sokvariant=arkivet&advanced=yes&antal=10

- "Förverkligandet av de språkliga rättigheterna förutsätter konkreta åtgärder". Finnish Government (in Swedish). 26 March 2009. Archived from the original on 13 September 2012. Retrieved 17 June 2022.

- "Wideroos: Dold anti-svensk agenda". svenska.yle.fi.

- "Den österbottniska kustregionen borde få en specialstatus - Vasabladet". Archived from the original on 18 July 2011. Retrieved 2 September 2009.

- "Befolkning efter språk 31.12.2000–2011. Ålands statistik- och utredningsbyrå".

- "Finland bor stadigvarande ca 8 500 svenska medborgare. Dessa utgör en heterogen grupp med många olika typer av bakgrund".

- "Syntymävaltio iän ja sukupuolen mukaan maakunnittain 1990 – 2012". Stat.fi (in Finnish). Tilastokeskus. Archived from the original on 21 July 2012. Retrieved 11 May 2013.

- "p.19 Via svenska – Den svenskspråkiga integrationsvägen" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 17 October 2017. Retrieved 24 July 2012.

- "Invandrare intresserade av svenska". svenska.yle.fi.

- "p.105 Via svenska – Den svenskspråkiga integrationsvägen" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 17 October 2017. Retrieved 24 July 2012.

- Löcke, Gerd-Peter. "IFISK – IFISK". www.ifisk.net.

- "Lead Group's domain". delaktig.fi.

- Vento, Isak; Harjula, Mikael; Himmelroos, Staffan (25 May 2020). "Den finlandssvenska diasporan". Politiikasta (in Swedish). Archived from the original on 9 June 2022. Retrieved 17 June 2022.

- Sundman, Sara (24 December 2017). "Följ med HBL till finlandssvenska Larsmont i Minnesota!". Hufvudstadsbladet (in Swedish). Archived from the original on 18 June 2022. Retrieved 18 June 2022.

- Alanen, Arnold Robert (2012). "Finland Swedes". Finns in Minnesota. St. Paul, Minn.: Minnesota Historical Society Press. ISBN 9780873518604. OCLC 918316682.

- Kepsu, Kaisa (2016), Hjärnflykt eller inte?: En analys av den svenskspråkiga flyttningen mellan Finland och Sverige 2000-2015 (PDF) (in Swedish), Tankesmedjan Magma, p. 4, ISBN 978-952-5864-67-0, ISSN 2342-7884, retrieved 17 June 2022

- Hakala, Heidi (16 October 2019). "Finlandssvensk rusch till Sverige, men det är svårt locka unga till föreningslivet". Hufvudstadsbladet (in Swedish). Archived from the original on 17 June 2022. Retrieved 17 June 2022.

- Fellman, Ulrika (17 October 2008). "'Hörni kläppar, sluta flajdas': Mark Levengood talade kring ämnet 'Språk och identitet'". Meddelanden (in Swedish). Åbo Akademi (14). Retrieved 17 June 2022.

Trots sitt svenska modersmål blev han tvungen att av principskäl gå en kurs i svenska för invandrare. Detta beskriver han som ett svårt slag, att han blev ifrågasatt då det gällde identiteten som svenskspråkig.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - Bülow, Anneli (3 May 2017). "Blir finlandssvenskarna en minoritet i Sverige?". Yle (in Swedish). Archived from the original on 17 June 2022. Retrieved 17 June 2022.

- Söderlund, Linda (15 November 2017). "Finlandssvenskarna får inte nationell minoritetsstatus i Sverige - vår historia är för kort". Yle (in Swedish). Archived from the original on 17 June 2022. Retrieved 17 June 2022.

- "11w1 -- Immigration and emigration by country of departure or arrival, sex and language, 1990-2021". Statistics Finland. Retrieved 9 September 2022.

- The Finns in America by Taru Spiegel, Reference Librarian. The Library of Congress.