THX 1138

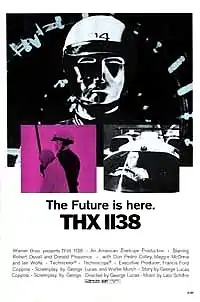

THX 1138 is a 1971 American social science fiction film directed and co-written by George Lucas in his feature film directorial debut. It is set in a dystopian future in which the populace is controlled through android police and mandatory use of drugs that suppress emotions. Produced by Francis Ford Coppola and written by Lucas and Walter Murch, it stars Robert Duvall and Donald Pleasence.

| THX 1138 | |

|---|---|

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | George Lucas |

| Screenplay by |

|

| Story by | George Lucas |

| Based on | Electronic Labyrinth: THX 1138 4EB by George Lucas |

| Produced by | Lawrence Sturhahn |

| Starring |

|

| Cinematography |

|

| Edited by | George Lucas |

| Music by | Lalo Schifrin |

Production company |

|

| Distributed by | Warner Bros. |

Release date |

|

Running time | 86 minutes[1] |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $777,777[2][3] |

| Box office | $2.4 million |

THX 1138 was developed from Lucas's student film Electronic Labyrinth: THX 1138 4EB, which he made in 1967 while attending the USC School of Cinematic Arts. The feature film was produced in a joint venture between Warner Bros. and American Zoetrope. A novelization by Ben Bova was published in 1971.

The film received mixed reviews from critics and underperformed at the box-office on initial release;[4] however, the film has subsequently received critical acclaim and gained a cult following, particularly in the aftermath of Lucas' success with Star Wars in 1977. A director's cut prepared by Lucas was released in 2004.

Plot

In the future, sexual intercourse and reproduction are prohibited, whereas use of mind-altering drugs is mandatory to enforce compliance among the citizens and to ensure their ability to conduct dangerous and demanding tasks. Emotions and the concept of family are taboo. Workers are clad in identical white uniforms and have shaven heads to emphasize uniformity, likewise with police androids who wear black and monks who are robed. Instead of names, people have designations with three arbitrary letters (referred to as the "prefix") and four digits, shown on an identity badge worn at all times.

At their jobs in central video control centers, SEN 5241 and LUH 3417 keep surveillance on the city. LUH has a male roommate, THX 1138, who works in a factory producing android police officers. At the beginning of the story, THX finishes his shift while the loudspeakers urge the workers to "increase safety"—and congratulate them for only losing 195 workers in the last period—to the competing factory's 242.

On the way home, he stops at a confession booth in a row of many, and relates his concerns and mumbles prayers about "party" and "masses", under the Jesus Christ-esque portrait of "OMM 0000". A soothing voice greets THX, and OMM ends the confession with a parting salutation: "You are a true believer, blessings of the State, blessings of the masses. Work hard, increase production, prevent accidents and be happy."

At home, THX takes his drugs and watches holobroadcasts while engaging with a masturbatory device. LUH secretly substitutes pills in her possession for THX's medications, causing him to develop nausea, anxiety, and sexual desires. LUH and THX become involved romantically and have sex. THX later is confronted by SEN, who attempts to arrange that THX become his new roommate, but THX files a complaint against SEN for the illegal shift pattern change.

Without drugs in his system, THX falters during a critical and hazardous phase of his job, and a control center engages a "mind lock" on THX which raises the level of danger. After the release of the mind lock, THX makes the necessary correction to that work phase. THX and LUH are arrested and THX undergoes drug therapy, and one of his kidneys is removed for donation purposes. He enjoys a brief reunion with LUH, disrupted shortly after she reveals her pregnancy.

At THX's trial, it is stated that THX was clinically born. It is decided that it would be inefficient to terminate THX, so THX is sentenced to prison, alongside SEN. The prison appears to be an all white space with no walls. One of the prisoners is a "shell dweller", later called a "Wookiee". The other prisoners seem uninterested in escape. THX and SEN walk to search for an exit. They walk and walk, with only a white space to be seen all around them. Eventually they are joined by hologram actor SRT 5752, who starred in the holobroadcasts. SRT 5752 shows them the exit and suggests to them that they may have been going in circles. During the escape, THX and SRT are separated from SEN. Chased by the police robots, THX and SRT are trapped in a control center, from which THX learns that LUH has been "consumed", and her name has been reassigned to her fetus, numbered 66691, in a growth chamber. SEN eventually escapes to an area reserved for the monks of OMM, where a monk notices that SEN has no identification badge. SEN attacks him and later wanders into a child-rearing area, strikes up a conversation with children and sits aimlessly until police androids apprehend him. THX and SRT steal two cars. SRT struggles with figuring out how to drive the car. When SRT finally gets the car to move, SRT immediately crashes his car into a concrete pillar.

Pursued by two police androids on motorcycles, THX flees to the limits of the city and escapes into a ventilation shaft. The police androids pursue him on motorcycles along the shaft to an escape ladder, but are ordered by Central Command to cease pursuit, on the grounds that the expense of his capture exceeds their allocated budget for THX. The guards inform THX that the surface is uninhabitable in a last-ditch attempt to convince him to surrender, but he is undeterred and continues up the ventilation shaft. The city is then revealed to be entirely underground, and THX has escaped onto the surface, where he then witnesses the Sun setting.

Cast

- Robert Duvall as THX 1138

- Donald Pleasence as SEN 5241

- Maggie McOmie as LUH 3417

- Don Pedro Colley as the hologram actor SRT 5752

- Ian Wolfe as the old prisoner PTO

- Marshall Efron as prisoner TWA

- Sid Haig as prisoner NCH

- John Pearce as prisoner DWY

- James Wheaton as the voice of OMM 0000

Additionally, amongst several 'announcer voices' were Scott Beach, Terence McGovern, and David Ogden Stiers (billed as David Ogden Steers). They had ties to the San Francisco Bay area, as did Lucas.

Production

THX 1138 was the first film made in a planned seven-picture slate commissioned by Warner Bros. from the 1969 incarnation of American Zoetrope.[5][6] Lucas wrote the initial script draft based on his earlier short film, but Coppola and Lucas agreed it was unsatisfactory. Murch assisted Lucas in writing an improved final draft.[2][3] For some of SEN's dialogue in the film, the script included excerpts from speeches by Richard Nixon.[7]

The script required almost the entire cast to shave their heads, either completely bald or with a buzz cut. As a publicity stunt, several actors were filmed having their first haircuts/shaves at unusual venues, with the results used in a promotional featurette titled Bald: The Making of THX 1138. Many of the shaven-headed extras seen in the film were recruited from the nearby Synanon, an addiction recovery program which became a violent cult.[8]

Filming began on September 22, 1969.[9] The schedule was between 35 and 40 days, completing in November 1969. Lucas filmed THX 1138 in Techniscope.[2][10]

Most locations for filming were in the San Francisco area,[11] including the unfinished tunnels of the Bay Area Rapid Transit subway system,[2][11][12] the Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory,[2] the Marin County Civic Center in San Rafael designed by Frank Lloyd Wright,[12] the Lawrence Hall of Science in Berkeley,[12] the San Francisco International Airport,[12] and at a remote manipulator for a hot cell. Several scenes show a large IBM System/360 multi-computer installation.[13] Studio sequences were shot at stages in Los Angeles, including a white stage 100 by 150 feet (30 by 46 m) for the "white limbo" sequences.[2] Lucas used entirely natural light.[12]

The chase scene featured two Lola T70 Mk III race cars[14] being chased by Yamaha TA125/250cc two-stroke, race-replica motorcycles through two San Francisco Bay Area automotive tunnels: the Caldecott Tunnel between Oakland and Orinda; and the underwater Posey Tube between Oakland and Alameda.[2] According to Caleb Deschanel, cars drove at speeds of 140 miles per hour (230 km/h) while filming the chase.[2] Other cars appearing in several scenes of the movie include the custom-built Ferrari Thomassima cars; one of them is on display in the Ferrari museum in Modena, Italy.[15]

The chase featured a motorcycle stunt. Stuntman Ronald "Duffy" Hambleton (credited as Duffy Hamilton) rode his police motorcycle full speed into a fallen paint stand, with a ramp built to Hambleton's specification. He flew over the handlebars, was hit by the airborne motorcycle, landed in the street on his back, and slammed into the crashed car in which Duvall's character had escaped.[2] According to Lucas, it turned out Hambleton was perfectly fine, apart from being angry with the people who had run into the shot to check on him. He was worried that they might have ruined the amazing stunt he had just performed by walking into frame.

THX's final climb out to the daylight was filmed (with the camera rotated 90°) in the incomplete (and decidedly horizontal) Bay Area Rapid Transit Transbay Tube before installation of the track supports, with the actors using exposed reinforcing bars on the floor of the tunnel as a "ladder".[2] The end scene, of THX standing before the sunset, was shot at Port Hueneme, California, by a second unit of (additional uncredited photographer) Caleb Deschanel and Matthew Robbins, who played THX in this long shot.[2]

After completion of photography, Coppola scheduled a year for Lucas to complete postproduction.[16] Lucas edited the film on a German-made K-E-M flatbed editor in his Mill Valley house by day, with Walter Murch editing sound at night; the two compared notes when they changed over.[2][16] Murch compiled and synchronized the sound montage, which includes all the "overhead" voices heard throughout the film, radio chatter, announcements, etc. The bulk of the editing was finished by mid-1970.

On completion of editing of the film, producer Coppola took it to Warner Bros., the financiers. Studio executives there disliked the film, and insisted that Coppola turn over the negative to an in-house Warner editor, who cut about four minutes of the film prior to release.[17]

Soundtrack

| THX 1138 | |

|---|---|

| Soundtrack album by Lalo Schifrin | |

| Released | 1970 |

| Recorded | October 15–16, 1970 |

| Studio | The Burbank Studios, Burbank, California, U.S. |

| Genre | Experimental |

| Length | 55:36 |

The soundtrack to the THX 1138, conducted by Lalo Schifrin, was released in 1970. Recording took place on October 15 and 16, 1970, at The Burbank Studios in Burbank, California, U.S.[18]

Track listing

- Logo – 00:08

- Main Title / What's Wrong? – 03:14

- Room Tone / Primitive Dance – 01:46

- Be Happy / LUH / Society Montage – 05:06

- Be Happy Again (Jingle of the Future) – 00:56

- Source #1 – 05:18

- Loneliness Sequence – 01:28

- SEN / Monks / LUH Reprise – 02:44

- You Have Nowhere to Go – 01:12

- Torture Sequence / Prison Talk Sequence – 03:42

- Love Dream / The Awakening – 01:47

- First Escape – 03:01

- Source #3 – 03:34

- Second Escape – 01:16

- Source #4 / Third Escape / Morgue Sequence / The Temple / Disruption / LUH's Death – 08:31

- Source #2 – 03:17

- The Hologram – 00:56

- First Chase / Foot Chase / St. Matthew's Passion (Bach) (End Credits) – 07:40

Reception

_by_Roger_Ebert_(cropped).jpg.webp)

THX 1138 was released to theaters on March 11, 1971 and was a commercial flop, earning back $945,000 in rentals for Warner Bros. but still leaving the studio in the red.[17] A contemporary survey found seven favorable, three mixed, and five negative reviews.[19]

Roger Ebert of the Chicago Sun-Times gave the film three stars out of four and wrote, "THX 1138 suffers somewhat from its simple storyline, but as a work of visual imagination it's special, and as haunting as parts of 2001: A Space Odyssey, Silent Running and The Andromeda Strain."[20] Gene Siskel of the Chicago Tribune awarded two stars out of four and stated, "The principal problem with this film is that it lacks imagination, the essential component of a science fiction film. Some persons might claim that the world of THX 1138 is here right now. A more reasonable opinion would hold that we are facing the problems of that world right now. Time has passed the film by."[21]

Vincent Canby of The New York Times wrote, "It is not, however, as either chase drama, or social drama, that THX 1138 is most interesting. Rather it's as a stunning montage of light, color and sound effects that create their own emotional impact ... Lucas's achievement in his first feature is all the more extraordinary when you realize that he is 25 years old, and that he shot most of the film in San Francisco, on a budget that probably would not cover the cost of half of one of the space ships in Stanley Kubrick's 2001."[22]

Arthur D. Murphy of Variety observed, "Likely not to be an artistic or commercial success in its own time, the American Zoetrope (Francis Ford Coppola group) production just might in time become a classic of stylistic, abstract cinema."[23] Charles Champlin of the Los Angeles Times praised the film as "a stunning deployment of the aural and visual resources of the screen to suggest a fearful new world of tyranny by technology," adding that "Lucas is obviously a master of cinematic effects with a special remarkable gift for discovering the look of the future in mundane places like parking structures and office corridors." Champlin stressed that the "real excitement of THX 1138 is not really the message but the medium—the use of film not to tell a story so much as to convey an experience, a credible impression of a fantastic and scary dictatorship of tomorrow."[24]

Kenneth Turan wrote in The Washington Post, "Fortunately, the film comes over not at all trite but rather as enormously affecting. Lucas obviously believed strongly in this futuristic vision, and the film draws its vitality and unity from his belief, and from the fact that it was not bottled up to meet arbitrary conditions but allowed the free rein necessary to reach completeness."[25] Penelope Houston of The Monthly Film Bulletin commented, "Details of the future society—control panels, monitor screens, soothing TV commercial voices, unshakeably calm robot policemen, the human animal turned automaton in appearance and function, but breaking out into a doomed love affair—are all tolerably persuasive, but in sum total rather a pile-up of predictability. On the Orwellian level of ideas, Lucas' passive new world is too indeterminate to carry enough conviction and, consequently, enough of a menacing charge."[26]

The film has continued to earn critical acclaim and holds an approval rating of 86% on Rotten Tomatoes based on 63 reviews, with an average score of 6.85/10. The consensus reads: "George Lucas' feature debut presents a spare, bleak, dystopian future, and features evocatively minimal set design and creepy sound effects."[27] On Metacritic it has a weighted average score of 75 out of 100 based on 8 reviews, indicating "generally favorable reviews".[28]

Awards

The film received a nomination at the 1971 Cannes Film Festival from the International Federation of Film Critics in the Directors' Fortnight section.[29]

Versions

1967 student film

The first version was a student film for USC School of Cinematic Arts titled Electronic Labyrinth: THX 1138 4EB. The run time was 15 minutes. It was released as a bonus feature on the 2004 Director's Cut.

1971 studio version

The 1971 studio version, distributed to theaters, had five minutes taken out (apparently against Lucas' wishes) by Warner Bros. studios. This version (81 minutes long) has never been released on any home media format.

1977 restored version

In 1977, after the success of Star Wars, THX 1138 was re-released with the footage that had been deleted by Warner Bros. edited back in, but it still did not gain popularity.[30] This version (86 minutes) was subsequently released on VHS and LaserDisc.

2004 director's cut

In 2004, The George Lucas Director's Cut of the film was released. Under Lucas' supervision, the film underwent an extensive restoration and digital intermediate process by Lowry Digital and Industrial Light & Magic (ILM), where the film's original negative was scanned, digital color correction was applied, and a brand new digital master was created.[31] Computer-generated imagery and audio/video restoration techniques were also applied to the film.[32][33]

At Lucas' request, the previsualization team at Skywalker Ranch worked in concert with ILM throughout the summer of 2003. The team also planned and executed a single day shoot, which would form the basis for new digital visual effects, mostly to expand scenes by extending crowds, filling out settings, and adding detail to the backgrounds of many scenes.[34]

These changes increased the run time of the film to 88 minutes. This director's cut was released to a limited number of digital-projection theaters on September 10, 2004, and then on DVD on September 14, 2004. The film was released on Blu-ray on September 7, 2010.[35] At that time, the film received an "R" rating (for "sexuality/nudity") from the MPAA, due to the changes to the ratings system since the original release (the original film was rated "GP", later changed to "PG"). It is the only film directed by Lucas to carry an "R" rating.[36]

Novelization

A novelization based on the film was written by Ben Bova and published in 1971.[37] It follows the plot of the movie closely, with four notable additions:

- An additional character, Control, is the accountant-like ultimate administrator of the city. Several passages depict the events from his point of view.

- After having sex with LUH 3417, THX 1138 consults a psychologist and admits everything. This psychologist transfers the confession to Control, leading to the overriding mindlock and arrest in the factory.

- LUH 3417's trial and death are depicted first-hand from her point of view, and from that of Control.

- Instead of climbing outside to witness a sunset, THX 1138 climbs up and spends the night in the superstructure, and exits in the morning to find other humans living outside.

Etymology and references

The significance of the name THX 1138 has been the subject of much speculation. In an interview for the DVD compilation Reel Talent, which included Lucas's original 4EB short, Lucas stated that he chose the letters and numbers for their aesthetic qualities, especially their symmetry.[38] According to the book Cinema by the Bay, published by LucasBooks, Lucas named the film after his telephone number while in college: 849-1138—the letters THX correspond to the numbers 8, 4, and 9 on the keypad.[39] However, Walter Murch states in the DVD's audio commentary that he always believed Lucas intended THX to be "sex", LUH to be "love", and SEN to be "sin".[7] John Lithgow, in "The Film School Generation" segment of the DVD series American Cinema, described the title THX 1138 as "reading like a license plate number."[40]

Numerous references to "1138" or "THX 1138" appear throughout the Star Wars films,[41] as well as other films by George Lucas. For example, THX 138 is the license plate number of John Milner's hot rod in American Graffiti. Lucas also founded THX Ltd., developer of the "THX" audio/visual reproduction standards.

See also

- List of American films of 1971

- List of films featuring surveillance

- Calling All Girls (Queen song)

- Utopian and dystopian fiction

References

- "THX 1138 (12)". British Board of Film Classification. May 28, 1971. Archived from the original on November 20, 2016. Retrieved October 15, 2022.

- Artifact from the Future: The Making of THX 1138 (DVD bonus disk accompanying THX 1138: The George Lucas Director's Cut). USA: Warner Bros. 2004.

- Pollock 1983, p. 89.

- Gilbey, Ryan. It Don't Worry Me. Faber & Faber.

- Pollock 1983, p. 88.

- Louise Sweeney, "The Movie Business is alive and well and living in San Francisco", Show, April 1970.

- Lucas 2004.

- Pollock 1983, p. 92.

- Lawrence Sturhahn, "Genesis of THX-1138: Notes on a Production", Kansas Quarterly, Spring 1972.

- Pollock 1983, pp. 90, 280.

- Pollock 1983, p. 91.

- Katie Dowd, "Before BART opened the Transbay Tube, they let George Lucas film a movie inside" Archived March 10, 2019, at the Wayback Machine, San Francisco Chronicle, March 10, 2019.

- E.g. Director's Cut at 1:11:52. 1:21:55, 1:25:35

- Breeze, Joe (January 5, 2015). "The police drove Lola T70s in George Lucas's directorial debut". Classic Driver. Archived from the original on December 8, 2015. Retrieved December 5, 2015.

- "Thomassima III is on display in the new Ferrari Museum in Modena"."Meade of Modena: An American Dreamer In the Land of Artful Science". Thomassima.com. Archived from the original on December 21, 2016. Retrieved January 1, 2017.

- Pollock 1983, p. 96.

- Pollock 1983, p. 97.

- "AllMusic". AllMusic. Archived from the original on August 9, 2020. Retrieved December 2, 2019.

- "THX 1138", FilmFacts, Vol XIV, No.7, 1971.

- Ebert, Roger. "THX 1138". RogerEbert.com. Archived from the original on May 11, 2019. Retrieved May 8, 2019.

- Siskel, Gene (May 18, 1971). "THX 1138". Chicago Tribune. Section 2, p. 4.

- Canby, Vincent (March 21, 1971). "Wanda's a Wow, So's THX". Archived May 14, 2019, at the Wayback Machine The New York Times. Section 2, p. 11.

- Murphy, Arthur D. (March 17, 1971). "Film Reviews: THX 1138". Variety. 18.

- Champlin, Charles (March 11, 1971). "New World of Tyranny in 'THX'". Los Angeles Times. Part IV, p. 1.

- Arnold, Gary (April 17, 1971). "THX 1138". The Washington Post. C6.

- Houston, Penelope (July 1971). "THX 1138". The Monthly Film Bulletin. 38 (450): 148.

- "THX 1138". Rotten Tomatoes. Archived from the original on May 4, 2011. Retrieved April 8, 2013.

- "THX 1138 Reviews". Metacritic. CBS Interactive. Archived from the original on December 25, 2015. Retrieved September 12, 2015.

- Higgins, Bill (May 9, 2018). "Hollywood Flashback: From 'THX 1138' to 'Sith,' George Lucas Is No Cannes Stranger". The Hollywood Reporter. Archived from the original on October 29, 2020. Retrieved September 27, 2020.

- Pollock 1983, p. 98.

- "THX 1138 by Lucasfilm". lucasfilm.com. Archived from the original on December 10, 2016. Retrieved December 27, 2016.

- Paul Hill; Henry Preston (October 11, 2004). "Back to the Future with 'THX 1138'". AWN.com (Interview). Interviewed by Bill Desowitz. Archived from the original on January 15, 2017. Retrieved December 27, 2016.

- "THX 1138 (1971)—Changes". Maverick Media. Archived from the original on May 2, 2009. Retrieved September 24, 2012.

- "THX 1138 (Comparison: Original Version - Director's Cut)". May 28, 2010. Archived from the original on November 12, 2020. Retrieved November 12, 2020.

- Calonge, Juan (May 10, 2010). "Warner Announces Sci-Fi Blu-ray Wave". Blu-ray.com. Archived from the original on May 13, 2010. Retrieved July 26, 2010.

- Ravalli, Richard (2016). "George Lucas Out of Love: Divorce, Darkness, and Reception in the Origin of PG‐13". The Historian. 78 (4): 690–709. doi:10.1111/hisn.12337. S2CID 151821638.

- Bova, Ben; Lucas, George (February 1, 1978). THX 1138. Warner Books. ISBN 0446897116.

- Reel Talent: First Films by Legendary Directors, DVD, 20th Century Fox, 2007

- Sheerly Avni (2006). Cinema by the Bay (Hardcover ed.). New York, NY: George Lucas Books. p. 36. ISBN 978-1-932183-88-7.

- Lithgow, John (host) (1995). American Cinema: The Film School Generation (Television Production).

- "Beyond a Cell Block: References to THX 1138 in Star Wars". StarWars.com. September 15, 2015. Archived from the original on January 21, 2018. Retrieved February 4, 2018.

Further reading

- Greene, Jr., James (2013). This Music Leaves Stains: The Complete Story of the Misfits. Scarecrow Press. ISBN 978-1589798922.

- Pollock, Dale (1983). Skywalking: The Life and Films of George Lucas. London: Elm Tree Books. ISBN 0-241-11034-3.

- Lucas, George (Director) (2004). THX 1138 (The George Lucas Director's Cut Two-Disc Special Edition) (DVD). USA: Warner Bros. ISBN 0-7907-6526-8. OCLC 56520465.

External links

- Official website at lucasfilm.com

- Official website at warnerbros.com

- THX 1138 at IMDb

- Interview with Don Pedro Colley about his experiences working on THX 1138 at LucasFan.com

- White on White Village Voice review April 8, 1971

- THX 1138 at Rotten Tomatoes

- THX 1138 at Metacritic