Taklamakan Desert

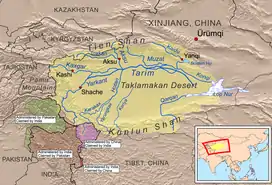

The Taklimakan or Taklamakan Desert (/ˌtæk.lə.məˈkæn/; Chinese: 塔克拉玛干沙漠; pinyin: Tǎkèlāmǎgān Shāmò, Xiao'erjing: تَاكْلامَاقًا شَاموْ, Dungan: Такәламаган Шамә; Uighur: تەكلىماكان قۇملۇقى, Täklimakan qumluqi; also spelled Taklimakan and Teklimakan) is a desert in Southwestern Xinjiang in Northwest China. It is bounded by the Kunlun Mountains to the south, the Pamir Mountains to the west, the Tian Shan range to the north, and the Gobi Desert to the east.

| Taklamakan Desert | |||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

View of the Taklamakan desert | |||||||||||||||||

Taklamakan Desert and Tarim Basin | |||||||||||||||||

| Area | 337,000 km2 (130,000 sq mi) | ||||||||||||||||

| Geography | |||||||||||||||||

| Country | China | ||||||||||||||||

| State/Province | Xinjiang | ||||||||||||||||

| Coordinates | 38.9°N 82.2°E | ||||||||||||||||

| Chinese name | |||||||||||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 塔克拉瑪干沙漠 | ||||||||||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 塔克拉玛干沙漠 | ||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||

| Dunganese name | |||||||||||||||||

| Dungan | Такәламаган Шамә | ||||||||||||||||

| Uyghur name | |||||||||||||||||

| Uyghur | تەكلىماكان قۇملۇقى | ||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||

Etymology

While most researchers agree on makan being the Persian word for "place", etymology of Takla is less clear. The word may be an Uyghur borrowing of the Persian tark, "to leave alone/out/behind, relinquish, abandon" + makan.[1][2] Another plausible explanation suggests it is derived from Turki taqlar makan, describing "the place of ruins".[3][4] Chinese scholars Wang Guowei and Huang Wenbi linked the name to the Tocharians, a historical people of the Tarim Basin, making the meaning of "Taklamakan" similar to "Tocharistan".[5] According to Uyghur scholar Turdi Mettursun Kara, the name Taklamakan comes from the expression Terk-i Mekan. The name is first mentioned as Terk-i Makan (ترك مكان / trk mkan) in the book called Tevarih-i Muskiyun, which was written in 1867 in the Hotan Prefecture of Xinjiang.[6]

In folk etymology, it is said to mean "Place of No Return" or "get in and you'll never get out".[7][8][9][10]

Geography

The Taklamakan Desert has an area of 337,000 km2 (130,000 sq mi),[11] making it slightly smaller than Germany. The desert is part of the Tarim Basin, which is 1,000 kilometres (620 mi) long and 400 kilometres (250 mi) wide. It is crossed at its northern and at its southern edge by two branches of the Silk Road, by which travellers sought to avoid the arid wasteland.[12] It is the world's second-largest shifting sand desert, with about 85% made up of shifting sand dunes,[13] ranking 17th in size in a ranking of the world's largest deserts.[14] Dunes range in height from 60 feet (18 m) up to as much as 300 feet (91 m). The few breaks in this sea of sand are small patches of alluvial clay. Generally, the steeper sides of the dunes face away from the prevailing winds.[15]

The People's Republic of China has constructed two cross-desert highways. The Tarim Desert Highway links the cities of Hotan (on the southern edge) and Luntai (on the northern edge) and the Bayingol to Ruoqiang road crosses the desert to the east.

In recent years, the desert has expanded in some areas, its sands enveloping farms and villages as a result of desertification.

"When I woke up one morning, I found I couldn't open the door because of the weight of sand that had accumulated overnight. My crops were buried too, so I had no choice but to move" -Memet Simay, Qira County resident[16]

The Golmud-Korla Railway crosses the Taklamakan as well.

Named areas in the desert include Ha-la-ma, A-lang-ha and Mai-k'o-tsa-k'o.[17] The Mazartag mountains are located in the western part of the desert.

Climate

Because it lies in the rain shadow of the Himalayas, Taklamakan has a cold desert climate. Given its relative proximity with the cold to frigid air masses in Siberia, extreme temperatures are recorded in wintertime, sometimes well below −20 °C (−4 °F), while in summer they can rise up to 40 °C (104 °F). During the 2008 Chinese winter storms episode, the Taklamakan was reported to be covered, for the first time in its recorded history, entirely with a thin layer of snow reaching 4 centimetres (1.6 in), with a temperature of −26.1 °C (−15 °F) in some observatories.[18]

Its extreme inland position, virtually in the very heartland of Asia and thousands of kilometres from any open body of water, accounts for the somewhat wide diurnal temperature variation.

Oasis

_p61_PLATE19._SINKIANG_(14597194848).jpg.webp)

The Taklamakan Desert has very little water, therefore it is hazardous to cross. Merchant caravans on the Silk Road would stop for relief at the thriving oasis towns.[20] It was in close proximity to many of the ancient civilizations—to the Northwest is the Amu Darya basin, to the southwest the Afghanistan mountain passes lead to Iran and India, to the east is China, and even to the north ancient towns such as Almaty can be found.

The key oasis towns, watered by rainfall from the mountains, were Kashgar, Miran, Niya, Yarkand, and Khotan (Hetian) to the south, Kuqa and Turpan in the north, and Loulan and Dunhuang in the east.[12] Now, many, such as Miran and Gaochang, are ruined cities in sparsely inhabited areas in the Xinjiang Autonomous Region of the People's Republic of China.[21]

The archaeological treasures found in its sand-buried ruins point to Tocharian, early Hellenistic, Indian, and Buddhist influences. Its treasures and dangers have been vividly described by Aurel Stein, Sven Hedin, Albert von Le Coq, and Paul Pelliot.[22] Mummies, some 4000 years old, have been found in the region.[23]

Later, the Taklamakan was inhabited by Turkic peoples. Starting with the Han dynasty, the Chinese sporadically extended their control to the oasis cities of the Taklamakan Desert to control the important silk route trade across Central Asia. Periods of Chinese rule were interspersed with rule by Turkic, Mongol and Tibetan peoples. The present population consists largely of Turkic Uyghur people and ethnic Han people.[24]

Scientific exploration

This desert was explored by several scholars, including Xuanzang, a 7th-century Buddhist monk, and, in the 20th century, the archaeologist Aurel Stein.

Atmospheric studies have shown that dust originating from the Taklamakan is blown over the Pacific, where it contributes to cloud formation over the Western United States. Further, the traveling dust redistributes minerals from the Taklamakan to the western U.S.A. via rainfall.[25] Studies have shown that a specific class of mineral found in the dust, known as K-feldspar, triggers ice formation particularly well. K-feldspar is particularly susceptible to corrosion by acidic atmospheric pollution, such as nitrates and phosphates; exposure to these constituents reduces the ability of the dust to trigger water droplet formation.[26]

In popular culture

The desert is the main setting for Chinese film series Painted Skin and Painted Skin: The Resurrection. The Chinese TV series Candle in the Tomb is mostly spent in this desert as they are searching for the ancient city of Jinjue (see Niya (Tarim Basin)).

The issue No. 39 'Soft Places' of Neil Gaiman's The Sandman takes place in the desert, when Marco Polo gets lost in the desert.

A portion of the Korean quasi-historical TV drama series Queen Seondeok takes place in the Taklamakan Desert. Sohwa escapes from Silla with baby Deokman and raises her in the desert. As a teenager, Deokman returns to Silla and uses the knowledge and experience gained from life among international traders in the Taklamakan trading centers to gain the throne of Silla.

The desert is showcased in the Japanese animation Mobile Suit Gundam 00, set in the year 2307. On the series, the Taklamakan Desert is the setting of a large-scale military joint operation performed by all the world's blocks of power, and interdicted by the paramilitary organization Celestial Being.

The Japanese anime Code Geass depicts a fictionalized version of Taklamakan Desert within the Chinese Federation, one of three superstates in the series. It serves as the setting of a key battle between the Holy Britannian Empire and Japanese insurrectionists backed by the Chinese Federation. Later, the presence of an underground city is revealed, where members of the Geass Order are being used by Emperor Charles zi Britannia and his consort Marianne vi Britannia to bring about the Ragnarök Connection.

See also

- Bezeklik Caves – Complex of Buddhist cave grottos

- Cities along the Silk Road

- List of deserts by area – List of the largest deserts in the world by area

- Mount Imeon – Ancient name for major Central Asia massif

- Taklamakania, named for the desert

- Tarim Basin – Endorheic basin in Northwest China

- Tarim mummies – Series of mummies discovered in the Tarim Basin

- Turpan water system – Irrigation system

References

Citations

- Pospelov, E. M. (1998). Geograficheskiye nazvaniya mira. Moscow. p. 408.

- Jarring, Gunnar (1997). "The Toponym Takla-makan". Turkic Languages. 1: 227–40.

- Tamm (2011), p. 139.

- "Takla Makan Desert at TravelChinaGuide.com". Archived from the original on October 25, 2008. Retrieved November 24, 2008. But see Christian Tyler, Wild West China, John Murray 2003, p.17

- Yao, Dali (2019). "Origin and meaning of the name "Taklamakan" [塔克拉玛干之名的起源与语义]". Wenhui Xueren (in Chinese). 408.

- Kara, Turdi Mettursun (March 1, 2022). ""Taklamakan" Adının Kökeni Üzerine". Korkut Ata Türkiyat Araştırmaları Dergisi (7): 572–577. doi:10.51531/korkutataturkiyat.1070366. ISSN 2687-5675. S2CID 248487312.

- Golden, Peter B. (January 14, 2011). Central Asia in World History. Oxford University Press. p. 16. ISBN 9780199722037.

- Hobbs, Joseph J. (December 14, 2007). World Regional Geography (6th ed.). Wadsworth Publishing Co Inc. p. 368. ISBN 978-0495389507. Archived from the original on February 19, 2017. Retrieved December 5, 2016.

- Baumer, Christoph (June 30, 2008). Traces in the Desert: Journeys of Discovery Across Central Asia. B. Tauris & Company. p. 141. ISBN 9780857718327. Archived from the original on February 19, 2017. Retrieved December 5, 2016.

- Hopkirk, Peter (November 1, 2001). Foreign Devils on the Silk Road: The Search for the Lost Treasures of Central Asia. Oxford University Press. p. 12. ISBN 978-0192802118. Archived from the original on February 19, 2017. Retrieved December 5, 2016.

- Sun, Jimin; Lou, Tungsten (2006). "The Age of the Taklimakan Desert". Science. 312 (5780): 1621. doi:10.1126/science.1124616. PMID 16778048. S2CID 21392336.

- Ban, Paul G. (2000). The Atlas of World Archeology. New York: Check mark Books. pp. 134&n dash, 135. ISBN 978-0-8160-4051-3.

- "Taklamakan Desert". Encyclopædia Britannica. Archived from the original on September 29, 2007. Retrieved August 11, 2007.

- "The World's Largest Desert". geology.com. Archived from the original on August 17, 2007. Retrieved August 22, 2007.

- Chisholm 1911, pp. 365–366.

- "Holding back the sands of time". China Daily. May 27, 2013. Retrieved December 15, 2019.

Memet Simay's household was one of 446 in Qira township forced to relocate in the 1980s, although the family has since returned to the area. "When I woke up one morning, I found I couldn't open the door because of the weight of sand that had accumulated overnight. My crops were buried too, so I had no choice but to move," he recalled.

- "NJ 44 Ho-tien [China, India] Series 1301, Edition 3-TPC". Washington, D. C.: U.S. Army Topographic Command. 1971 – via Perry–Castañeda Library Map Collection.

KJ A-LANG-HA HA-LA-MA MAI-K'O-TSA-K'O LH{...}LEGEND{...}AREA NAME HA-LA-MA

- "China's biggest desert Taklamakan experiences record snow". Xinhuanet.com. February 1, 2008. Archived from the original on February 8, 2008. Retrieved February 4, 2008.

- "38°53'28.0"n 82°10'40.0"e".

- Hopkirk, Peter (2001). Spies Along the Silk Road. ISBN 9780192802323. Archived from the original on January 9, 2017. Retrieved August 7, 2007.

- Whitfield, Susan; Library, British (2004). The Silk Road: Trade, Travel, War and Faith. ISBN 9781932476132. Archived from the original on May 9, 2016. Retrieved August 25, 2007.

- "The Silk Road". Archived from the original on March 15, 2016. Retrieved August 7, 2007.

- Wade, Nicholas (March 15, 2010). "A Host of Mummies, a Forest of Secrets". The New York Times. Archived from the original on December 28, 2014. Retrieved December 28, 2014.

- Xinjiang territory profile Archived July 1, 2018, at the Wayback Machine, BBC News. May 7, 2011.

- Fox, Douglas (December 22, 2014). "The Dust Detectives". High Country News. Vol. 46, no. 22. Archived from the original on August 19, 2017. Retrieved September 2, 2017.

- Atkinson, James D.; Murray, Benjamin J.; Woodhouse, Matthew T.; Whale, Thomas F.; Baustian, Kelly J.; Carslaw, Kenneth S.; Dobbie, Steven; O’Sullivan, Daniel; Malkin, Tamsin L. (June 2013). "The importance of feldspar for ice nucleation by mineral dust in mixed-phase clouds" (PDF). Nature. 498 (7454): 355–358. Bibcode:2013Natur.498..355A. doi:10.1038/nature12278. PMID 23760484. S2CID 4423734.

Sources

- Jarring, Gunnar (1997). "The toponym Takla-makan", Turkic Languages, Vol. 1, pp. 227–240.

- Hopkirk, Peter (1980). Foreign Devils on the Silk Road: The Search for the Lost Cities and Treasures of Chinese Central Asia. Amherst: The University of Massachusetts Press. ISBN 0-87023-435-8.

- Hopkirk, Peter (1994). The Great Game: The Struggle for Empire in Central Asia. ISBN 1-56836-022-3.

- Tamm, Eric Enno (2010). The Horse That Leaps Through Clouds. Vancouver/Toronto/Berkeley: Douglas & McIntyre. ISBN 9781553652694 (cloth); ISBN 978-1-55365-638-8 (ebook).

- Warner, Thomas T. (2004). Desert Meteorology. Cambridge University Press, 612 pages. ISBN 0-521-81798-6.

Further reading

- Cariou, Alain (2010). "Taklamakan". Encyclopaedia Iranica.

- Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 26 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 365–366.

Videography

- Treasure seekers : China's frozen desert, National Geographic Society (2001)