Tattoo

A tattoo is a form of body modification made by inserting tattoo ink, dyes, and/or pigments, either indelible or temporary, into the dermis layer of the skin to form a design. Tattoo artists create these designs using several tattooing processes and techniques, including hand-tapped traditional tattoos and modern tattoo machines. The history of tattooing goes back to Neolithic times, practiced across the globe by many cultures, and the symbolism and impact of tattoos varies in different places and cultures.

Tattoos may be decorative (with no specific meaning), symbolic (with a specific meaning to the wearer), or pictorial (a depiction of a specific person or item). Many tattoos serve as rites of passage, marks of status and rank, symbols of religious and spiritual devotion, decorations for bravery, marks of fertility, pledges of love, amulets and talismans, protection, and as punishment, like the marks of outcasts, slaves and convicts. Extensive decorative tattooing has also been part of the work of performance artists such as tattooed ladies.

Today, people choose to be tattooed for artistic, cosmetic, sentimental/memorial, religious, and spiritual reasons, and family and to symbolize their belonging to or identification with particular groups, including criminal gangs (see criminal tattoos) or a particular ethnic group or law-abiding subculture. Tattoos may show how a person feels about a relative (commonly a parent or child) or about an unrelated person.[1]

Tattoos can also be used for functional purposes, such as identification, permanent makeup, and medical purposes.

Terminology

The word tattoo, or tattow in the 18th century, is a loanword from the Samoan word tatau, meaning "to strike".[2][3] The Oxford English Dictionary gives the etymology of tattoo as "In 18th c. tattaow, tattow. From Polynesian (Samoan, Tahitian, Tongan, etc.) tatau. In Marquesan, tatu." Before the importation of the Polynesian word, the practice of tattooing had been described in the West as painting, scarring, or staining.[4]

The etymology of the body modification term is not to be confused with the origins of the word for the military drumbeat or performance — see military tattoo. In this case, the English word tattoo is derived from the Dutch word taptoe.[5]

Copyrighted tattoo designs that are mass-produced and sent to tattoo artists are known as "flash".[6] Flash sheets are prominently displayed in many tattoo parlors for the purpose of providing both inspiration and ready-made tattoo images to customers.

The Japanese word irezumi means "insertion of ink" and can mean tattoos using tebori, the traditional Japanese hand method, a Western-style machine or any method of tattooing using insertion of ink. The most common word used for traditional Japanese tattoo designs is horimono.[7] Japanese may use the word tattoo to mean non-Japanese styles of tattooing.

British anthropologist Ling Roth in 1900 described four methods of skin marking and suggested they be differentiated under the names "tatu", "moko", "cicatrix", and "keloid".[8] The first is by pricking that leaves the skin smooth as found in places including the Pacific Islands. The second is a tattoo combined with chiseling to leave furrows in the skin as found in places including New Zealand. The third is scarification using a knife or chisel as found in places including West Africa. The fourth and the last is scarification by irritating and re-opening a preexisting wound, and re-scarification to form a raised scar as found in places including Tasmania, Australia, Melanesia, and Central Africa.[9]

Types

The American Academy of Dermatology distinguishes five types of tattoos: traumatic tattoos that result from injuries, such as asphalt from road injuries or pencil lead; amateur tattoos; professional tattoos, both via traditional methods and modern tattoo machines; cosmetic tattoos, also known as "permanent makeup"; and medical tattoos.[10]

Traumatic tattoos

A traumatic tattoo occurs when a substance such as asphalt or gunpowder is rubbed into a wound as the result of some kind of accident or trauma.[11] When this involves carbon, dermatologists may call the mark a carbon stain instead of a tattoo.[12]: 47 Coal miners could develop characteristic marks owing to coal dust getting into wounds.[13] These are particularly difficult to remove as they tend to be spread across several layers of skin, and scarring or permanent discoloration is almost unavoidable depending on the location. An amalgam tattoo is when amalgam particles are implanted in to the soft tissues of the mouth, usually the gums, during dental filling placement or removal.[14] Another example of such accidental tattoos is the result of a deliberate or accidental stabbing with a pencil or pen, leaving graphite or ink beneath the skin.

Forcible tattooing for identification

A well-known example is the Nazi practice of forcibly tattooing concentration camp inmates with identification numbers during the Holocaust as part of the Nazis' identification system, beginning in fall 1941.[15] The SS introduced the practice at Auschwitz concentration camp in order to identify the bodies of registered prisoners in the concentration camps. During registration, guards would pierce the outlines of the serial-number digits onto the prisoners' arms. Of the Nazi concentration camps, only Auschwitz put tattoos on inmates.[16] The tattoo was the prisoner's camp number, sometimes with a special symbol added: some Jews had a triangle, and Romani had the letter "Z" (from German Zigeuner for "Gypsy"). In May 1944, Jewish men received the letters "A" or "B" to indicate a particular series of numbers.

As early as the Zhou, Chinese authorities would employ facial tattoos as a punishment for certain crimes or to mark prisoners or slaves.

During the Roman Empire, gladiators and slaves were tattooed: exported slaves were tattooed with the words "tax paid", and it was a common practice to tattoo "fugitive" (denoted by the letters "FUG") on the foreheads of runaway slaves.[17] Owing to the Biblical strictures against the practice,[18] Emperor Constantine I banned tattooing the face around AD 330, and the Second Council of Nicaea banned all body markings as a pagan practice in AD 787.[19]

Cultural identification

In the period of early contact between the Māori and Europeans, the Māori people hunted and decapitated each other for their moko tattoos, which they traded for European items including axes and firearms.[20] Moko tattoos were facial designs worn to indicate lineage, social position, and status within the tribe. The tattoo art was a sacred marker of identity among the Māori and also referred to as a vehicle for storing one's tapu, or spiritual being, in the afterlife.[21]

Postmortem identification

Tattoos are sometimes used by forensic pathologists to help them identify burned, putrefied, or mutilated bodies. As tattoo pigment lies encapsulated deep in the skin, tattoos are not easily destroyed even when the skin is burned.[22]

Identification of animals

Pets, show animals, thoroughbred horses, and livestock are sometimes tattooed with animal identification marks. Ear tattoos are a method of identification for beef cattle.[23] Tattooing with a 'slap mark' on the shoulder or on the ear is the standard identification method in commercial pig farming. Branding is used for similar reasons and is often performed without anesthesia, but is different from tattooing as no ink or dye is inserted during the process, the mark instead being caused by permanent scarring of the skin.[24] Pet dogs and cats are sometimes tattooed with a serial number (usually in the ear, or on the inner thigh) via which their owners can be identified. However, the use of a microchip has become an increasingly popular choice and since 2016 is a legal requirement for all 8.5 million pet dogs in the UK.[25]

Cosmetic

Permanent makeup is the use of tattoos to enhance eyebrows, lips (liner and/or lipstick), eyes (liner), and even moles, usually with natural colors, as the designs are intended to resemble makeup.[26]

A growing trend in the US and UK is to place artistic tattoos over the surgical scars of a mastectomy. "More women are choosing not to reconstruct after a mastectomy and tattoo over the scar tissue instead... The mastectomy tattoo will become just another option for post cancer patients and a truly personal way of regaining control over post cancer bodies..."[27] However, the tattooing of nipples on reconstructed breasts remains in high demand.[28]

Medical

Medical tattoos are used to ensure instruments are properly located for repeated application of radiotherapy and for the areola in some forms of breast reconstruction. Tattooing has also been used to convey medical information about the wearer (e.g., blood group, medical condition, etc.). Alzheimer patients may be tattooed with their names, so they may be easily identified if they go missing.[29] Additionally, tattoos are used in skin tones to cover vitiligo, a skin pigmentation disorder.[30]

SS blood group tattoos (German: Blutgruppentätowierung) were worn by members of the Waffen-SS in Nazi Germany during World War II to identify the individual's blood type. After the war, the tattoo was taken to be prima facie, if not perfect, evidence of being part of the Waffen-SS, leading to potential arrest and prosecution. This led a number of ex-Waffen-SS to shoot themselves through the arm with a gun, removing the tattoo and leaving scars like the ones resulting from pox inoculation, making the removal less obvious.[31]

Tattoos were probably also used in ancient medicine as part of the treatment of the patient. In 1898, Daniel Fouquet, a medical doctor, wrote an article on "medical tattooing" practices in Ancient Egypt, in which he describes the tattooed markings on the female mummies found at the Deir el-Bahari site. He speculated that the tattoos and other scarifications observed on the bodies may have served a medicinal or therapeutic purpose: "The examination of these scars, some white, others blue, leaves in no doubt that they are not, in essence, ornament, but an established treatment for a condition of the pelvis, very probably chronic pelvic peritonitis."[32]

Ötzi the iceman had a total of 61 tattoos, which may have been a form of acupuncture used to relieve pain.[33] Radiological examination of Ötzi's bones showed "age-conditioned or strain-induced degeneration" corresponding to many tattooed areas, including osteochondrosis and slight spondylosis in the lumbar spine and wear-and-tear degeneration in the knee and especially in the ankle joints.[34] If so, this is at least 2,000 years before acupuncture's previously known earliest use in China (c. 100 BCE).

History

Preserved tattoos on ancient mummified human remains reveal that tattooing has been practiced throughout the world for thousands of years.[35] In 2015, scientific re-assessment of the age of the two oldest known tattooed mummies identified Ötzi as the oldest example then known. This body, with 61 tattoos, was found embedded in glacial ice in the Alps, and was dated to 3250 BCE.[35][36] In 2018, the oldest figurative tattoos in the world were discovered on two mummies from Egypt which are dated between 3351 and 3017 BCE.[37]

Ancient tattooing was most widely practiced among the Austronesian people. It was one of the early technologies developed by the Proto-Austronesians in Taiwan and coastal South China prior to at least 1500 BCE, before the Austronesian expansion into the islands of the Indo-Pacific.[38][39] It may have originally been associated with headhunting.[40] Tattooing traditions, including facial tattooing, can be found among all Austronesian subgroups, including Taiwanese Aborigines, Islander Southeast Asians, Micronesians, Polynesians, and the Malagasy people. Austronesians used the characteristic hafted skin-puncturing technique, using a small mallet and a piercing implement made from Citrus thorns, fish bone, bone, and oyster shells.[2][39][41]

Ancient tattooing traditions have also been documented among Papuans and Melanesians, with their use of distinctive obsidian skin piercers. Some archeological sites with these implements are associated with the Austronesian migration into Papua New Guinea and Melanesia. But other sites are older than the Austronesian expansion, being dated to around 1650 to 2000 BCE, suggesting that there was a preexisting tattooing tradition in the region.[39]

Among other ethnolinguistic groups, tattooing was also practiced among the Ainu people of Japan; some Austroasians of Indochina; Berber women of Tamazgha (North Africa);[42] the Yoruba, Fulani and Hausa people of Nigeria;[43] Native Americans of the Pre-Columbian Americas;[44] and Picts of Iron Age Britain.[45]

Europe

In 1566, French sailors abducted an Inuit woman and her child in modern-day Labrador and brought her to the city of Antwerp in the Dutch Republic. The mother was tattooed while the child was unmarked. In Antwerp, the two were put on display at a local tavern at least until 1567, with handbills promoting the event being distributed in the city. In 1577, English privateer Martin Frobisher captured two Inuit and brought them back to England for display. One of the Inuit was a tattooed woman from Baffin Island, who was illustrated by the English cartographer John White.[50]

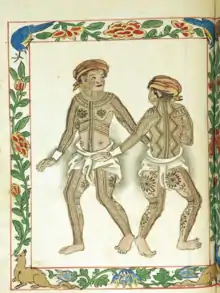

In 1691, William Dampier brought to London a Filipino man named Jeoly or Giolo from the island of Mindanao (Philippines) who had a tattooed body. Dampier exhibited Jeoly in a human zoo to make a fortune and falsely branded him as a "prince" to draw large crowds. At the time of exhibition, Jeoly was still grieving his mother, who Dampier also enslaved and had died at sea during their exploitation to Europe. Dampier claimed that he became friends with Jeoly, but with the intention to make money, he continued to exploit his "friend" by exhibiting him in a human zoo, where Jeoly died three months later. Jeoly's dead body was afterwards skinned, and his skinless body was disposed, while the tattooed skin was sold and displayed at Oxford.[51]

It is commonly held that the modern popularity of tattooing stems from Captain James Cook's three voyages to the South Pacific in the late 18th century. Certainly, Cook's voyages and the dissemination of the texts and images from them brought more awareness about tattooing (and, as noted above, imported the word "tattow" into Western languages).[52] On Cook's first voyage in 1768, his science officer and expedition botanist, Sir Joseph Banks, as well as artist Sydney Parkinson and many others of the crew, returned to England with a keen interest in tattoos with Banks writing about them extensively[53] and Parkinson is believed to have gotten a tattoo himself in Tahiti.[54] Banks was a highly regarded member of the English aristocracy who had acquired his position with Cook by co-financing the expedition with ten thousand pounds, a very large sum at the time. In turn, Cook brought back with him a tattooed Raiatean man, Omai, whom he presented to King George and the English Court. On subsequent voyages other crew members, from officers, such as American John Ledyard, to ordinary seamen, were tattooed.[55]

The first documented professional tattooist in Britain was Sutherland Macdonald, who operated out of a salon in London beginning in 1894.[56] In Britain, tattooing was still largely associated with sailors[57] and the lower or even criminal class,[58] but by the 1870s had become fashionable among some members of the upper classes, including royalty,[4][59] and in its upmarket form it could be an expensive[60] and sometimes painful[61] process. A marked class division on the acceptability of the practice continued for some time in Britain.[62]

Tattooing of Catholic women in Bosnia and Herzegovina became widespread during the Ottoman rule and continued to the mid 20th century. Among the Catholic population, there was a widespread tradition of tattooing crosses on the hands, arms, chest, and forehead of girls between the ages of 6 to 16.[63] This was done in order to prevent kidnapping by the Ottoman Turks and conversion to Islam.[64] Ethnographers believe that its origins predate both the Slavic migration to the Balkans and spread of Christianity, with evidence pointing far back to the prehistoric Illyrian tribes.[64]

North America

Many Indigenous peoples of North America practice tattooing.[65] European explorers and traders who met Native Americans noticed these tattoos and wrote about them, and a few Europeans chose to be tattooed by Native Americans.[66] See history of tattooing in North America.

By the time of the American Revolution, tattoos were already common among American sailors (see sailor tattoos).[67] Tattoos were listed in protection papers, an identity certificate issued to prevent impressment into the British Royal Navy.[67] Because protection papers were proof of American citizenship, Black sailors used them to show that they were freemen.[68]

The first recorded professional tattoo shop in the US was established in the early 1870s by a German immigrant, Martin Hildebrandt.[69][70] He had served as a Union soldier in the Civil War and tattooed many other soldiers.[70]

Soon after the Civil War, tattoos became fashionable among upper-class young adults. This trend lasted until the beginning of World War I. The invention of the electric tattoo machine caused popularity of tattoos among the wealthy to drop off. The machine made the tattooing procedure both much easier and cheaper, thus, eliminating the status symbol tattoos previously held, as they were now affordable for all socioeconomic classes. The status symbol of a tattoo shifted from a representation of wealth to a mark typically seen on rebels and criminals. Despite this change, tattoos remained popular among military servicemen, a tradition that continues today.

In 1975, there were only 40 tattoo artists in the country; in 1980, there were more than 5,000 self-proclaimed tattoo artists,[71] appearing in response to sudden demand.[72]

Many studies have been done of the tattooed population and society's view of tattoos. In June 2006, the Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology published the results of a telephone survey of 2004: it found that 36% of Americans ages 18–29, 24% of those 30–40, and 15% of those 41–51 had a tattoo.[73] In September 2006, the Pew Research Center conducted a telephone survey that found that 36% of Americans ages 18–25, 40% of those 26–40 and 10% of those 41–64 had a tattoo. They concluded that Generation X and Millennials express themselves through their appearance, and tattoos are a popular form of self-expression.[74] In January 2008, a survey conducted online by Harris Interactive estimated that 14% of all adults in the United States have a tattoo, slightly down from 2003, when 16% had a tattoo. Among age groups, 9% of those ages 18–24, 32% of those 25–29, 25% of those 30–39 and 12% of those 40–49 have tattoos, as do 8% of those 50–64. Men are slightly more likely to have a tattoo than women.

Since the 1970s, tattoos have become a mainstream part of Western fashion, common both for men and women, and among all economic classes[75] and to age groups from the later teen years to middle age. For many young Americans, the tattoo has taken on a decidedly different meaning than for previous generations. The tattoo has undergone "dramatic redefinition" and has shifted from a form of deviance to an acceptable form of expression.[76]

As of 1 November 2006, Oklahoma became the last state to legalize tattooing, having banned it since 1963.[77]

Australia

Branding was used by European authorities for marking criminals throughout the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries.[78] The practice was also used by British authorities to mark army deserters and military personnel court-martialed in Australia. In nineteenth century Australia tattoos were generally the result of personal rather than official decisions but British authorities started to record tattoos along with scars and other bodily markings to describe and manage convicts assigned for transportation.[48] The practice of tattooing appears to have been a largely non-commercial enterprise during the convict period in Australia. For example, James Ross in the Hobart Almanac of 1833 describes how the convicts on board ship commonly spent time tattooing themselves with gunpowder.[48] Out of a study of 10,180 convict records that were transported to then Van Diemen's Land (now Tasmania) between 1823 and 1853 about 37% of all men and about 15% of all women arrived with tattoos, making Australia at the time the most heavily tattooed English-speaking country.[79]

By the beginning of the twentieth century, there were tattoo studios in Australia but they do not appear to have been numerous. For example, the Sydney tattoo studio of Fred Harris was touted as being the only tattoo studio in Sydney between 1916 and 1943.[80] Tattoo designs often reflected the culture of the day and in 1923 Harris's small parlour experienced an increase in the number of women getting tattoos. Another popular trend was for women to have their legs tattooed so the designs could be seen through their stockings.[81]

By 1937 Harris was one of Sydney's best-known tattoo artists and was inking around 2000 tattoos a year in his shop. Sailors provided most of the canvases for his work but among the more popular tattoos in 1938 were Australian flags and kangaroos for sailors of the visiting American Fleet.[82]

In modern day Australia a popular tattoo design is the Southern Cross motif, or variations of it.[71] There are currently over 2000 official tattoo practitioners in Australia and over 100 registered parlours and clinics, with the number of unregistered parlours and clinics are estimated to be double that amount. The demand over the last decade for tattoos in Australia has risen over 440%, making it an in demand profession in the country.[83]

There are several large tattoo conventions held in Australia, some of which are considered the biggest in the southern hemisphere, with the best artists from around Oceana attending.[84][85]

Process

Tattooing involves the placement of pigment into the skin's dermis, the layer of dermal tissue underlying the epidermis. After initial injection, pigment is dispersed throughout a homogenized damaged layer down through the epidermis and upper dermis, in both of which the presence of foreign material activates the immune system's phagocytes to engulf the pigment particles. As healing proceeds, the damaged epidermis flakes away (eliminating surface pigment) while deeper in the skin granulation tissue forms, which is later converted to connective tissue by collagen growth. This mends the upper dermis, where pigment remains trapped within successive generations of macrophages, ultimately concentrating in a layer just below the dermis/epidermis boundary. Its presence there is stable, but in the long term (decades) the pigment tends to migrate deeper into the dermis, accounting for the degraded detail of old tattoos.[86]

Equipment

Some tribal cultures traditionally created tattoos by cutting designs into the skin and rubbing the resulting wound with ink, ashes or other agents; some cultures continue this practice, which may be an adjunct to scarification. Some cultures create tattooed marks by hand-tapping the ink into the skin using sharpened sticks or animal bones (made into needles) with clay formed disks or, in modern times, actual needles.

The most common method of tattooing in modern times is the electric tattoo machine, which inserts ink into the skin via a single needle or a group of needles that are soldered onto a bar, which is attached to an oscillating unit. The unit rapidly and repeatedly drives the needles in and out of the skin, usually 80 to 150 times a second. The needles are single-use needles that come packaged individually, or manufactured by artists, on-demand, as groupings dictate on a per-piece basis.

In modern tattooing, an artist may use thermal stencil paper or hectograph ink/stencil paper to first place a printed design on the skin before applying a tattoo design.

Practice regulation and health risk certification

Tattooing is regulated in many countries because of the associated health risks to client and practitioner, specifically local infections and virus transmission. Disposable plastic aprons and eye protection can be worn depending on the risk of blood or other secretions splashing into the eyes or clothing of the tattooist. Hand hygiene, assessment of risks and appropriate disposal of all sharp objects and materials contaminated with blood are crucial areas. The tattoo artist must wash his or her hands and must also wash the area that will be tattooed. Gloves must be worn at all times and the wound must be wiped frequently with a wet disposable towel of some kind. All equipment must be sterilized in a certified autoclave before and after every use. It is good practice to provide clients with a printed consent form that outlines risks and complications as well as instructions for after care.[87]

Associations

Historical associations

Among Austronesian societies, tattoos had various functions. Among men, they were strongly linked to the widespread practice of head-hunting raids. In head-hunting societies, like the Ifugao and Dayak people, tattoos were records of how many heads the warriors had taken in battle, and were part of the initiation rites into adulthood. The number, design, and location of tattoos, therefore, were indicative of a warrior's status and prowess. They were also regarded as magical wards against various dangers like evil spirits and illnesses.[88] Among the Visayans of the pre-colonial Philippines, tattoos were worn by the tumao nobility and the timawa warrior class as permanent records of their participation and conduct in maritime raids known as mangayaw.[89][90] In Austronesian women, like the facial tattoos among the women of the Tayal and Māori people, they were indicators of status, skill, and beauty.[91][92]

The Government of Meiji Japan had outlawed tattoos in the 19th century, a prohibition that stood for 70 years before being repealed in 1948.[93] As of 6 June 2012, all new tattoos are forbidden for employees of the city of Osaka. Existing tattoos are required to be covered with proper clothing. The regulations were added to Osaka's ethical codes, and employees with tattoos were encouraged to have them removed. This was done because of the strong connection of tattoos with the yakuza, or Japanese organized crime, after an Osaka official in February 2012 threatened a schoolchild by showing his tattoo.

Tattoos had negative connotations in historical China, where criminals often had been marked by tattooing.[94][95] The association of tattoos with criminals was transmitted from China to influence Japan.[94] Today, tattoos have remained a taboo in Chinese society.[96]

The Romans tattooed criminals and slaves, and in the 19th century released U.S. convicts, Australian convicts and British army deserters were identified by tattoos. Prisoners in Nazi concentration camps were tattooed with an identification number. Today, many prison inmates still tattoo themselves as an indication of time spent in prison.[4]

Native Americans also used tattoos to represent their tribe.[97] Catholic Croats of Bosnia used religious Christian tattooing, especially of children and women, for protection against conversion to Islam during the Ottoman rule in the Balkans.[98]

Modern associations

Tattoos are strongly empirically associated with deviance, personality disorders and criminality.[99][100] Although the general acceptance of tattoos is on the rise in Western society, they still carry a heavy stigma among certain social groups.[101] Tattoos are generally considered an important part of the culture of the Russian mafia.[102]

Current cultural understandings of tattoos in Europe and North America have been greatly influenced by long-standing stereotypes based on deviant social groups in the 19th and 20th centuries. Particularly in North America, tattoos have been associated with stereotypes, folklore and racism.[21] Not until the 1960s and 1970s did people associate tattoos with such societal outcasts as bikers and prisoners.[103] Today, in the United States many prisoners and criminal gangs use distinctive tattoos to indicate facts about their criminal behavior, prison sentences and organizational affiliation.[104] A teardrop tattoo, for example, can be symbolic of murder, or each tear represents the death of a friend. At the same time, members of the U.S. military have an equally well-established and longstanding history of tattooing to indicate military units, battles, kills, etc., an association that remains widespread among older Americans. In Japan, tattoos are associated with yakuza criminal groups, but there are non-yakuza groups such as Fukushi Masaichi's tattoo association that sought to preserve the skins of dead Japanese who have extensive tattoos. Tattooing is also common in the British Armed Forces. Depending on vocation, tattoos are accepted in a number of professions in America. Companies across many fields are increasingly focused on diversity and inclusion.[105] Mainstream art galleries hold exhibitions of both conventional and custom tattoo designs, such as Beyond Skin, at the Museum of Croydon.[106]

In Britain, there is evidence of women with tattoos, concealed by their clothing, throughout the 20th century, and records of women tattooists such as Jessie Knight from the 1920s.[107] A study of "at-risk" (as defined by school absenteeism and truancy) adolescent girls showed a positive correlation between body modification and negative feelings towards the body and low self-esteem; however, the study also demonstrated that a strong motive for body modification is the search for "self and attempts to attain mastery and control over the body in an age of increasing alienation".[108] The prevalence of women in the tattoo industry in the 21st century, along with larger numbers of women bearing tattoos, appears to be changing negative perceptions.

In Covered in Ink by Beverly Yuen Thompson, she interviews heavily tattooed women in Washington, Miami, Orlando, Houston, Long Beach, and Seattle from 2007 to 2010 using participant observation and in-depth interviews of 70 women. Younger generations are typically more unbothered by heavily tattooed women, while older generation including the participants parents are more likely to look down on them, some even go to the extreme of disowning their children for getting tattoos.[109] Typically how the family reacts is an indicator of their relationship in general. Family members who weren't accepting of tattoos often wanted to scrub the images off, pour holy water on them or have them surgically removed. Families who were emotionally accepting of their family members were able to maintain close bonds after tattooing.[110]

Advertising and marketing

Former sailor Rowland Hussey Macy, who formed Macy's department stores, used a red star tattoo that he had on his hand for the store's logo.[111]

Tattoos have also been used in marketing and advertising with companies paying people to have logos of brands like HBO, Red Bull, ASOS.com and Sailor Jerry's rum tattooed in their bodies.[112] This practice is known as "skinvertising".[113]

B.T.'s Smokehouse, a barbecue restaurant located in Massachusetts, offered customers free meals for life if they had the logo of the establishment tattooed on a visible part of their bodies. Nine people took the business up on the offer.[114]

Health risks

The pain of tattooing can range from uncomfortable to excruciating depending on the location of the tattooing the body. The pain can cause fainting.

Because it requires breaking the immunologic barrier formed by the skin, tattooing carries health risks including infection and allergic reactions. Modern tattooists reduce health risks by following universal precautions working with single-use items and sterilizing their equipment after each use. Many jurisdictions require that tattooists have blood-borne pathogen training such as that provided through the Red Cross and OSHA. As of 2009 (in the United States) there have been no reported cases of HIV contracted from tattoos.[115]

In amateur tattooing, such as the practice in prisons, there is an elevated risk of infection. Infections that can theoretically be transmitted by the use of unsterilized tattoo equipment or contaminated ink include surface infections of the skin, fungal infections, some forms of hepatitis, herpes simplex virus, HIV, staph, tetanus, and tuberculosis.[116]

Tattoo inks have been described as "remarkably nonreactive histologically".[86] However, cases of allergic reactions to tattoo inks, particularly certain colors, have been medically documented. This is sometimes due to the presence of nickel in an ink pigment, which triggers a common metal allergy. Occasionally, when a blood vessel is punctured during the tattooing procedure, a bruise/hematoma may appear. At the same time, a number of tattoo inks may contain hazardous substances, and a proposal has been submitted by the European Chemicals Agency (ECHA) to restrict the intentional use or concentration limit of approximately 4000 substances when contained in tattoo inks.[117] According to a study by the European Union Observatory for Nanomaterials (EUON), a number of modern-day tattoo inks contain nanomaterials.[118] These engender significant nanotoxicological concerns.

Certain colours – red or similar colours such as purple, pink, and orange – tend to cause more problems and damage compared to other colours.[119] Red ink has even caused skin and flesh damages so severe that the amputation of a leg or an arm has been necessary. If part of a tattoo (especially if red) begins to cause even minor troubles, like becoming itchy or worse, lumpy, then Danish experts strongly suggest to remove the red parts.[120]

In 2017, researchers from the European Synchrotron Radiation Facility in France say the chemicals in tattoo ink can travel in the bloodstream and accumulate in the lymph nodes, obstructing their ability to fight infections. However, the authors noted in their paper that most tattooed individuals including the donors analyzed do not suffer from chronic inflammation.[121]

Tattoo artists frequently recommend sun protection of skin to prevent tattoos from fading and to preserve skin integrity to make future tattooing easier.[122][123]

Removal

While tattoos are considered permanent, it is sometimes possible to remove them, fully or partially, with laser treatments. Typically, carbon based pigments, or iron-oxide-based pigments, as well as some colored inks can be removed more completely than inks of other colors. The expense and pain associated with removing tattoos are typically greater than the expense and pain associated with applying them. Methods other than laser tattoo removal methods include dermabrasion, salabrasion (scrubbing the skin with salt), reduction techniques, cryosurgery and excision—which is sometimes still used along with skin grafts for larger tattoos. These older methods, however, have been nearly completely replaced by laser removal treatment options.[124]

Temporary tattoos

A temporary tattoo is a non-permanent image on the skin resembling a permanent tattoo. As a form of body painting, temporary tattoos can be drawn, painted, or airbrushed.[125][126]

Decal-style temporary tattoos

Decal (press-on) temporary tattoos are used to decorate any part of the body. They may last for a day or for more than a week.[127]

Metallic jewelry tattoos

Foil temporary tattoos are a variation of decal-style temporary tattoos, printed using a foil stamping technique instead of using ink.[128] The foil design is printed as a mirror image in order to be viewed in the right direction once it is applied to the skin. Each metallic tattoo is protected by a transparent protective film.

Airbrush temporary tattoos

Although they have become more popular and usually require a greater investment, airbrush temporary tattoos are less likely to achieve the look of a permanent tattoo, and may not last as long as press-on temporary tattoos. An artist sprays on airbrush tattoos using a stencil with alcohol-based cosmetic inks. Like decal tattoos, airbrush temporary tattoos also are easily removed with rubbing alcohol or baby oil.

Henna temporary tattoos

Another tattoo alternative is henna-based tattoos, which generally contain no additives. Henna is a plant-derived substance which is painted on the skin, staining it a reddish-orange-to-brown color. Because of the semi-permanent nature of henna, they lack the realistic colors typical of decal temporary tattoos. Due to the time-consuming application process, it is a relatively poor option for children. Dermatological publications report that allergic reactions to natural henna are very rare and the product is generally considered safe for skin application. Serious problems can occur, however, from the use of henna with certain additives. The FDA and medical journals report that painted black henna temporary tattoos are especially dangerous.

Decal-style temporary tattoo safety

Decal temporary tattoos, when legally sold in the United States, have had their color additives approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) as cosmetics – the FDA has determined these colorants are safe for "direct dermal contact". While the FDA has received some accounts of minor skin irritation, including redness and swelling, from this type of temporary tattoo, the agency has found these symptoms to be "child specific" and not significant enough to support warnings to the public. Unapproved pigments, however, which are sometimes used by non-US manufacturers, can provoke allergic reactions in anyone.

Airbrush tattoo safety

The types of airbrush paints manufactured for crafting, creating art or decorating clothing should never be used for tattooing. These paints can be allergenic or toxic.

Henna tattoo safety

The FDA regularly issues warnings to consumers about avoiding any temporary tattoos labeled as black henna or pre-mixed henna as these may contain potentially harmful ingredients including silver nitrate, carmine, pyrogallol, disperse orange dye and chromium. Black henna gets its color from paraphenylenediamine (PPD), a textile dye approved by the FDA for human use only in hair coloring.[129] In Canada, the use of PPD on the skin, including hair dye, is banned. Research has linked these and other ingredients to a range of health problems including allergic reactions, chronic inflammatory reactions, and late-onset allergic reactions to related clothing and hairdressing dyes. They can cause these reactions long after application. Neither black henna nor pre-mixed henna are approved for cosmetic use by the FDA.

Religious views

Egyptians originally used tattoos to show dedication to a god, and the tattoos were believed to convey divine protection. In Hinduism, Buddhism, and Neopaganism, tattoos are accepted.[130] Southeast Asia has a tradition of protective tattoos variously known as sak yant or yantra tattoos that include Buddhist images, prayers, and symbols. Images of the Buddha or other religious figures have caused controversy in some Buddhist countries when incorporated into tattoos by Westerners who do not follow traditional customs regarding respectful display of images of Buddhas or deities.

Judaism generally prohibits tattoos among its adherents based on the commandments in Leviticus 19. Jews tend to believe this commandment only applies to Jews and not to gentiles. However, an increasing number of young Jews are getting tattoos either for fashion, or an expression of their faith.[131]

There is no specific teaching in the New Testament prohibiting tattoos. Most Christian denominations believe that the Old Covenant ceremonial laws in Leviticus were abrogated with the coming of the New Covenant; that the prohibition of various cultural practices, including tattooing, was intended to distinguish the Israelites from neighbouring peoples for a limited period of time, and was not intended as a universal law to apply to the gentiles for all time. Many Coptic Christians in Egypt have a cross tattoo on their right wrist to differentiate themselves from Muslims.[132] However, some Evangelical and fundamentalist Protestant denominations believe the commandment applies today for Christians and believe it is a sin to get a tattoo. In Catholic teaching, what is said in Leviticus (19:28) is taught not binding upon Christians for the same reason that the verse “nor shall there come upon you a garment of cloth made of two kinds of stuff” (Lev. 19:19) is not binding upon Christians. It is a matter of what the tattoo depicts. The Catholic Church says the images should not be immoral, such as sexually explicit, Satanic, or in any way opposed to the truths and teachings of Christianity.[133]

Tattoos are considered to be haram for many Sunni Muslims, based on rulings from scholars and passages in the Sunni Hadith. Shia Islam does not prohibit tattooing,[134][135] and many Shia Muslims (Lebanese, Iraqis, Yemenis, Iranians) have tattoos, specifically with religious themes.[135]

In popular culture

- Inked (magazine), a tattoo lifestyle digital media company that bills itself as the outsiders' insider media

- See List of tattoo TV shows

See also

Styles

- Black-and-gray

- Borneo traditional tattooing

- Chinese calligraphy tattoos

- Christian tattooing in Bosnia and Herzegovina

- Criminal tattoo

- Deq (tattoo)

- Irezumi, traditional Japanese tattoo

- New school (tattoo)

- Old school (tattoo)

- Pe'a

- Prison tattooing

- Sailor tattoos

- Scarification

- Sleeve tattoo

- Soot tattoo

- SS blood group tattoo

Location

- Body suit (tattoo)

- Genital tattooing

- Lower back tattoo

- Scleral tattooing

Others

- Biomechanical art

- Body art

- Body painting

- Mehndi (also called henna)

- Foreign body granuloma

- Fusen gum

- Legal status of tattooing in European countries

- Legal status of tattooing in the United States

- List of tattoo artists

- Lucky Diamond Rich, world's most tattooed person

- Religious perspectives on tattooing

- Tattoo convention

- Tattooed lady

References

Citations

- Johnson, Frankie J (2007). "Tattooing: Mind, Body And Spirit. The Inner Essence Of The Art". Sociological Viewpoints. 23: 45–61.

- Thompson, Beverly Yuen (2015). ""I Want to Be Covered": Heavily Tattooed Women Challenge the Dominant Beauty Culture" (PDF). Covered in Ink: Tattoos, Women and the Politics of the Body. New York, New York USA: New York University Press. pp. 35–64. ISBN 9780814789209.

- Meaning of Tatau 1, Pasefika Design

- "tattoo". The Hutchinson Unabridged Encyclopedia with Atlas and Weather guide (Credo Reference. Web. ed.). Helicon. July 2021.

- OED

- "Tattoo History: Flash Art". Cloak and Dagger. Retrieved 17 August 2018.

- "History Of Irezumi/Horimono". Oni Tattoo Design. Retrieved 17 August 2018.

- Roth, H. Ling (11 September 1900). On Permanent Artificial Skin Marks: a definition of terms. Bradford: Anthropological Section of the British Association for the Advancement of Science.

- McDougall, Russell and Davidson, Iain; eds. (2016). The Roth Family, Anthropology, and Colonial Administration, p.97. Routledge. ISBN 9781315417288.

- "Tattoos, Body Piercings, and Other Skin Adornments". Aad.org. Archived from the original on 23 December 2010. Retrieved 5 April 2012.

- "10.18 Traumatic Tattoos and Abrasions". Emergency Medicine Informatics. Archived from the original on 7 September 2017. Retrieved 17 August 2018.

- James, William D.; Berger, Timothy G.; et al. (2006). Andrews' Diseases of the Skin: clinical Dermatology. Saunders Elsevier. ISBN 978-0-7216-2921-6.

- Orwell, George (1940). "Down the Mine". Inside the Whale.

- "Amalgam tattoo". Royal Berkshire Hospital. Archived from the original on 10 February 2018. Retrieved 17 August 2018.

- "Tattoos and Numbers: The System of Identifying Prisoners at Auschwitz". www.ushmm.org.

- "Tattoos and Numbers: The System of Identifying Prisoners at Auschwitz". encyclopedia.ushmm.org. Retrieved 11 October 2019.

- "Pitt Rivers Museum Body Arts | Prisoner's tag". web.prm.ox.ac.uk.

- Leviticus 19:28

- Mayor, Adrienne (March–April 1999). "People Illustrated". Archaeological Institute of America. Vol. 52, no. 2.

- "A Strange Trade — Deals in Maori Heads — Pioneer Artists". victoria.ac.nz.

- Atkinson, Michael (2003). Tattooed: the sociogenesis of a body art. ISBN 9780802085689. Retrieved 5 April 2012.

- Khunger, Niti; Molpariya, Anupama; Khunger, Arjun (2015). "Complications of Tattoos and Tattoo Removal: Stop and Think Before you ink". Journal of Cutaneous and Aesthetic Surgery. 8 (1): 30–36. doi:10.4103/0974-2077.155072. ISSN 0974-2077. PMC 4411590. PMID 25949020.

- "Some Ways To Indentify [sic] Beef Cattle". The Beef Site. Retrieved 15 October 2018.

- Small, Richard. "REVIEW OF LIVESTOCK IDENTIFICATION AND TRACEABILITY IN THE UK". GOV.UK. DEFRA, Farm Animal Genetic Resources Committee. Retrieved 17 March 2017.

- "Compulsory dog microchipping comes into effect". Government Digital Service. Retrieved 17 March 2017.

- "Permanent Make-Up". NHS. Retrieved 20 August 2018.

- Locke, Katherine. 2013. "Women choose body art over reconstruction after cancer battle: Undergoing a mastectomy is a harrowing experience, but tattoos can celebrate the victory over cancer." The Guardian. 7 August 2013.

- "Nipple tattoos and their Michelangelo". BBC News. 21 December 2013.

- Hürriyet Daily News: Tattooist offers to tattoo names of Alzheimer patients in İzmir

- Arndt, Kenneth A.; Hsu, Jeffrey T. S. (2007). Manual of Dermatologic Therapeutics (illustrated ed.). Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. p. 116. ISBN 978-0781760584. Retrieved 6 September 2013.

- Lepre, George (2004). Himmler's Bosnian Division: The Waffen-SS Handschar Division 1943–1945. Schiffer Publishing Ltd. p. 310. ISBN 978-0764301346.

- Gemma Angel, "Tattooing in Ancient Egypt Part 2: The Mummy of Amunet". 10 December 2012.

- Piombino-Mascali, Dario; Krutak, Lars (4 January 2020). "Therapeutic Tattoos and Ancient Mummies: The Case of the Iceman". Purposeful Pain: The Bioarchaeology of Intentional Suffering. Bioarchaeology and Social Theory: 119–136. doi:10.1007/978-3-030-32181-9_6. ISBN 978-3-030-32180-2. S2CID 213402907. Retrieved 28 April 2021.

- Spindler, Konrad (2001). The Man in the Ice. pp. 178–184. ISBN 978-0-7538-1260-0.

- Deter-Wolf, Aaron; Robitaille, Benoît; Krutak, Lars; Galliot, Sébastien (February 2016). "The World's Oldest Tattoos" (PDF). Journal of Archaeological Science: Reports. 5: 19–24. doi:10.1016/j.jasrep.2015.11.007.

- Scallan, Marilyn (9 December 2015). "Ancient Ink: Iceman Otzi Has World's Oldest Tattoos". Smithsonian Science News. Retrieved 19 December 2015.

- Ghosh, Pallab (1 March 2018). "'Oldest tattoo' found on 5,000-year-old Egyptian mummies". BBC. Retrieved 8 March 2018.

- Patrick Vinton Kirch (2012). A Shark Going Inland Is My Chief: The Island Civilization of Ancient Hawai'i. University of California Press. pp. 31–32. ISBN 9780520273306.

- Furey, Louise (2017). "Archeological Evidence for Tattooing in Polynesia and Micronesia". In Lars Krutak & Aaron Deter-Wolf (ed.). Ancient Ink: The Archaeology of Tattooing. University of Washington Press. pp. 159–184. ISBN 9780295742847.

- Baldick, Julian (2013). Ancient Religions of the Austronesian World: From Australasia to Taiwan. I.B.Tauris. p. 3. ISBN 9781780763668.

- "Maori Tattoo". Maori.com. Maori Tourism Limited. Archived from the original on 20 July 2015. Retrieved 17 July 2015.

- Corbett, Sarah (6 February 2016). "Facial Tattooing of Berber Women". Ethnic Jewels Magazine. Retrieved 18 May 2018.

- Wilson-Fall, Wendy (Spring 2014). "The Motive of the Motif Tattoos of Fulbe Pastoralists". African Arts. 47 (1): 54–65. doi:10.1162/AFAR_a_00122. S2CID 53477985.

- Evans, Susan, Toby. 2013. Ancient Mexico and Central America: Archaeology and Culture History. 3rd Edition.

- Carr, Gillian (2005). "Woad, tattoing, and identity in later Iron Age and Early Roman Britain". Oxford Journal of Archaeology. 24 (3): 273–292. doi:10.1111/j.1468-0092.2005.00236.x.

- "The True Story of the Mindanaoan Slave Whose Skin Was Displayed at Oxford". Esquiremag.ph.

- Savage, John (c. 1692). "Etching of Prince Giolo". State Library of New South Wales.

- Maxwell-Stewart, Hamish, in Caplan, J. (2000). Written on the body: The tattoo in European and American history / edited by Jane Caplan. London: Reaktion. ISBN 1-86189-062-1

- Barnes, Geraldine (2006). "Curiosity, Wonder, and William Dampier's Painted Prince". Journal for Early Modern Cultural Studies. 6 (1): 31–50. doi:10.1353/jem.2006.0002. S2CID 159686056.

- Krutak, Lars (22 August 2013). "Myth Busting Tattoo (Art) History". Lars Krutak: Tattoo Anthropologist. Retrieved 25 February 2020.

- Mangubat (2017). The True Story of the Mindanaoan Slave Whose Skin Was Displayed at Oxford. Esquire.

- "Captain Cook, Sir Joseph Banks and tattoos in Tahiti". Royal Museums Greenwich. 25 August 2015. Retrieved 3 April 2020.

- Knows, The Dear (6 June 2010). "Sir Joseph Banks and the Art of Tattoo". The Dear Surprise. Retrieved 3 April 2020.

- Gallacher, Stevie. "The story of Scots explorer and artist Sydney Parkinson, who joined Captain Cook's expedition armed with pencils and paint". The Sunday Post. Retrieved 3 April 2020.

- "The Cook Myth: Common Tattoo History Debunked". tattoohistorian.com. 5 April 2014.

- "The man who started the tattoo craze in Britain is coming to a museum near you". The Independent. Archived from the original on 26 May 2022. Retrieved 20 July 2018.

- Some days after a shipwreck divers recovered the bodies. Most were unrecognisable, but that of a crew member was readily identified by his tattoos: "The reason why sailors tattoo themselves has often been asked." The Times (London), 30 January 1873, p. 10

- The Times (London), 3 April 1879, p. 9: "Crime has a ragged regiment in its pay so far as the outward ... qualities are concerned ... they tattoo themselves indelibly ... asserting the man's identity with the aid of needles and gunpowder. This may be the explanation of the Mermaids, the Cupid's arrows, the name of MARY, the tragic inscription to the memory of parents, the unintended pathos of the appeal to liberty."

- Broadwell, Albert H. (27 January 1900). "Sporting pictures on the human skin". Country Life. Article describing work of society tattooist Sutherland Macdonald Archived 3 November 2013 at the Wayback Machine refers to his clientele including "members of our Royal Family, among them H.R.H. the Duke of York, H.I.M. the Czarevitch, and Imperial and Royal members of Russian, German and Spanish courts...."

- The Times (London), 18 April 1889, p. 12: "A Japanese Professional Tattooer". Article describes the activities of an unnamed Japanese tattooist based in Hong Kong. He charged £4 for a dragon, which would take 5 hours to do. The article ends "The Hong-Kong operator tattooed the arm of an English Prince, and, in Kioto, was engaged for a whole month reproducing on the trunk and limbs of an English peer a series of scenes from Japanese history. For this he was paid about £100. He has also tattooed ladies.... His income from tattooing in Hong Kong is about £1,200 per annum."

- Broadwell, Albert H. (27 January 1900). "Sporting pictures on the human skin". Country Life. "In especially sensitive cases a mild solution of cocaine is injected under the skin, ... and no sensation whatever is felt, while the soothing solution is so mild that it has no effect ... except locally."

- In 1969 the House of Lords debated a bill to ban the tattooing of minors, on grounds it had become "trendy" with the young in recent years but was associated with crime, 40 per cent of young criminals having tattoos. Lord Teynham and the Marquess of Aberdeen and Temair however rose to object that they had been tattooed as youngsters, with no ill effects. The Times (London), 29 April 1969, p. 4: "Saving young from embarrassing tattoos".

- Medić Bošnjak, Marija (20 February 2018). "Stari običaj 'križićanje' ili "sicanje" izumire". ljportal.com.

- Jukić, Monika. "Tradicionalno tetoviranje Hrvata u Bosni i Hercegovini - bocanje kao način zaštite od Osmanlija". academia.edu.

- Root, Leeanne (13 September 2018). "How Native American Tattoos Influenced the Body Art Industry". Indian Country Today. Retrieved 12 June 2022.

- Friedman Herlihy, Anna Felicity (June 2012). Tattooed Transculturites: Western Expatriates among Amerindian and Pacific Islander Societies, 1500–1900 (PhD). Chicago, IL: University of Chicago.

- Dye, Ira (1989). "The Tattoos of Early American Seafarers, 1796-1818". Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society. 133 (4): 520–554. ISSN 0003-049X. JSTOR 986875.

- Law in American History: Volume 1: From the Colonial Years Through the Civil War. Page 305.

- Nyssen, Carmen. "New York City's 1800s Tattoo Shops". Buzzworthy Tattoo History. Retrieved 6 June 2022.

- Amer, Aïda; Laskow, Sarah (13 August 2018). "Tattooing in the Civil War Was a Hedge Against Anonymous Death". Atlas Obscura. Retrieved 5 June 2022.

- "Think before you ink: Tattoo risks". Mayo Clinic. Retrieved 26 April 2022.

- "Original Tattoo Artist: Times Changing". The Washington Post. 9 November 1980. ISSN 0190-8286. Retrieved 5 March 2019.

- Kirby, David (2012). Inked Well. Patterns for College Writing: A Rhetorical Reader and Guide: Bedford/St. Martins. pp. 685–689. ISBN 9780312676841.

- "A Portrait of 'Generation Next'". The Pew Research Center for the People and the Press. 9 January 2007. Retrieved 5 April 2012.

- "History, Ink - The Valentine". Google Arts & Culture. Retrieved 20 April 2020.

- Roberts, D. J. (2012). "Secret Ink: Tattoo's Place in Contemporary American Culture". Journal of American Culture. 35 (2): 153–65. doi:10.1111/j.1542-734x.2012.00804.x. PMID 22737733.

- "State last to legalize tattoo artists, parlors". Chicago Tribune. 11 May 2006. Retrieved 6 June 2019.

- Clare Andersen in Caplan, J. (2000). Written on the body: The tattoo in European and American history / edited by Jane Caplan. London: Reaktion. ISBN 1-86189-062-1

- "Tattoo trend goes back to Tasmania's convict era, author finds". ABC News. 30 August 2016.

- PIX MAgazine, Vol. 1 No. 4 (19 February 1938)

- SYDNEY WOMEN'S CRAZE. (6 October 1923). Maryborough Chronicle, Wide Bay and Burnett Advertiser (Qld. : 1860 - 1947), p. 11

- Fred Harris Tattoo Studio Sydney, 1916-1943, State Library of New South Wales

- "Tattoo Removal Stats and Facts".

- "Rites Of Passage Tattoo Festival | Melbourne & Sydney". ritesofpassagefestival.com. Retrieved 18 July 2022.

- "Australian Tattoo Expo | 300+ Tattoo Artists Under One Roof". www.tattooexpo.com.au. Retrieved 18 July 2022.

- "Tattoo Lasers: Overview, Histology, Tattoo Removal Techniques". Medscape. 13 September 2017.

- "Tattooing and body piercing guidance: Toolkit" (PDF). Chartered Institute of Environmental Health. Retrieved 17 March 2017.

- DeMello, Margo (2014). Inked: Tattoos and Body Art around the World. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 9781610690768.

- William Henry Scott (1994). Barangay: sixteenth-century Philippine culture and society. Ateneo de Manila University Press.

- José S. Arcilla (1998). An Introduction to Philippine History. Ateneo de Manila University Press. p. 14–16. ISBN 9789715502610.

- Major-General Robley (1896). "Moko and Mokamokai – Chapter I – How Moko First Became Knows to Europeans". Moko; or Maori Tattooing. Chapman and Hall Limited. p. 5. Retrieved 26 September 2009.

- Lach, Donald F. & Van Kley, Edwin J. (1998). Asia in the Making of Europe, Volume III: A Century of Advance. Book 3: Southeast Asia. University of Chicago Press. p. 1499. ISBN 9780226467689.

- Ito, Masami, "Whether covered or brazen, tattoos make a statement", Japan Times, 8 June 2010, p. 3

- DeMello, Margo (2007). Encyclopedia of body adornment. Westport: Greenwood Press. p. 61. ISBN 978-0-313-33695-9.

- Dutton, Michael (1998). Streetlife China. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 163 & 180. ISBN 978-0-521-63141-9.

- Dutton, Michael (1998). Streetlife China. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 180. ISBN 978-0-521-63141-9.

- "Native American Tattoos". Cloak and Dagger Tattoo London. 30 September 2020. Retrieved 26 April 2022.

- Truhelka, Ciro. Wissenschaftliche Mittheilungen Aus Bosnien und der Hercegovina: "Die Tätowirung bei den Katholiken Bosniens und der Hercegovina." Sarajevo; Bosnian National Museum, 1896.

- Wesley G. Jennings; Bryanna Hahn Fox; David P. Farrington (14 January 2014), "Inked into Crime? An Examination of the Causal Relationship between Tattoos and Life-Course Offending among Males from the Cambridge Study in Delinquent Development", Journal of Criminal Justice, 42 (1, January–February 2014): 77–84, doi:10.1016/j.jcrimjus.2013.12.006

- Adams, Joshua (2012), "The Relationship between Tattooing and Deviance in Contemporary Society", Deviance Today, pp. 137–145

- "Society And Tattoos". HuffPost UK. 4 April 2017. Retrieved 26 May 2019.

- Hodgkinson, Will (26 October 2010). "Russian criminal tattoos: breaking the code". The Guardian. Retrieved 21 September 2018.

- Bodies of Inscription: A Cultural History of the Modern Tattoo Community. Margo DeMello. Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2000. vii + 222 pp., photographs, notes, bibliography, index.

- Lichtenstein, Andrew, Texas Prison Tattoos, retrieved 8 December 2007

- Hennessey, Rachel (8 March 2013). "Tattoos No Longer A Kiss Of Death In The Workplace - Yahoo! Small Business Advisor". Smallbusiness.yahoo.com. Retrieved 15 March 2013.

- "Beyond Skin". Museum of Croydon. Archived from the original on 17 August 2018. Retrieved 17 August 2018.

- Mifflin, Margot (2013). Bodies of Subversion: A secret history of women and tattoo (3rd ed.). Powerhouse Books. p. 192. ISBN 978-1576876138.

- Carroll, L.; Anderson, R. (2002), "Body piercing, tattooing, self-esteem, and body investment in adolescent girls", Adolescence, 37 (147): 627–37, PMID 12458698

- Thompson, Beverly Yuen (24 July 2015). Covered in Ink. New York University Press. doi:10.18574/nyu/9780814760000.001.0001. ISBN 978-0-8147-6000-0.

- Thompson, Beverly Yuen (2015). Covered in Ink: Tattoos, Women and the Politics of the Body. New York University Press. pp. 87–88.

- Binkley, Christina. 2016. "Departments of Commerce." Wall Street Journal Magazine. |work=New York University Press September 2016. Page 168.

- Allen, Kevin (25 June 2013). "'Your ad here?' Marketers turn to tattoos". PR Daily. Ragan Communications, Inc. Retrieved 18 April 2014.

- Hines, Alice (30 May 2013). "The Tattoo As Corporate Branding Tool". Details. Condé Nast. Retrieved 18 April 2014.

- Boynton, Donna (19 February 2013). "B.T.'s Smokehouse logo tattoo earns patrons free meals for life". Telegram.com. Worcester Telegram & Gazette Corp. Retrieved 18 April 2014.

- "HIV and Its Transmission". CDC. July 1999. Archived from the original on 4 March 2010.

- "Tattoos: Risks and precautions to know first". MayoClinic.com. 20 March 2012. Retrieved 5 April 2012.

- "Proposal to restrict hazardous substances in tattoo inks and permanent make-up - All news - ECHA". echa.europa.eu. Retrieved 26 October 2018.

- "Literature study on the uses and risks of nanomaterials as pigments in the European Union". European Union Observatory for Nanomaterials (EUON).

- "Gode råd om tatoveringer: De her farver skal du undgå". 26 March 2014.

- Danish TV programme "Min krop til andres forfærdelse" or "My body to the dismay of others" aired on DR 3 1.July 9pm CEST. A man who at a younger age had competed with his older brother to obtain the largest tattoos, experienced an infection years later originating in the red portions of the tattoos, resulting in his left leg being amputated piece by piece. Also, a woman with incipient problems at her two formerly red roses was followed as her skin was removed.

- "Tattoo Ink Nanoparticles Persist in Lymph Nodes". The Scientist.

- "Re: Cutaneous melanoma attributable to sunbed use: systematic review and meta-analysis". The BMJ: e4757. 18 September 2018.

- Rosenbaum, Brooke E.; Milam, Emily C.; Seo, Lauren; Leger, Marie C. (2016). "Skin Care in the Tattoo Parlor: A Survey of Tattoo Artists in New York City". Dermatology. 232 (4): 484–489. doi:10.1159/000446345. ISSN 1018-8665. PMID 27287431.

- Images of Tattoo removal procedure, retrieved 12 January 2011

- "Temporary Vs. Permanent Tattoos: Which One Should You Get? - Saved Tattoo". 2 March 2021. Retrieved 26 April 2022.

- How to remove temporary tattoos, 15 July 2021, retrieved 22 July 2021

- "Temporary Tattoos, Henna/Mehndi, and "Black Henna"". FDA. Retrieved 3 August 2015.

- Baldwin, Pepper (5 April 2016). DIY Temporary Tattoos: Draw It, Print It, Ink It. Macmillan. p. 28. ISBN 978-1-250-08770-6.

- "FDA warns consumers about dangers of temporary tattoos". Fox News. 26 March 2013. Retrieved 3 August 2015.

- Ferguson, Matthew (31 October 2018). "Opinions on tattoos differ by religion". Webster Journal. Retrieved 13 April 2019.

- Torgovnick, Kate (17 July 2008). "For Some Jews, It Only Sounds Like 'Taboo'". New York Times. Retrieved 17 August 2018.

- Campo, Juan E.; Iskander, John (26 October 2006). The Coptic Community. doi:10.1093/oxfordhb/9780195137989.001.0001. ISBN 9780195137989.

- Catholic Answers, Matt. "What does the Church Teach about Tattoos?". catholic.com. Retrieved 16 May 2021.

- Mar 23, <img src='https://imagesvc meredithcorp io/v3/mm/image?url=https%3A%2F%2Fstatic onecms io%2Fwp-content%2Fuploads%2Fsites%2F13%2F2021%2F03%2F15%2F45D62555-57A4-4099-B4D7-3A7CC0387C44 jpeg' alt='' width='48' /> Anmol Irfan. "My Muslim Culture Says Tattoos Are Haram-But Are They?". HelloGiggles. Retrieved 26 April 2022.

- "Are Tattoos Haram? - A Complete Guide • Muslimversity". Muslimversity. 30 March 2020. Retrieved 26 April 2022.

General sources

- Anthropological

- Buckland, A. W. (1887). "On Tattooing", in Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute of Great Britain and Ireland, 1887/12, p. 318–328

- Caplan, Jane (ed.) (2000): Written on the Body: the Tattoo in European and American History, Princeton University Press

- DeMello, Margo (2000) Bodies of Inscription: a Cultural History of the Modern Tattoo Community, California. Durham NC: Duke University Press

- Fisher, Jill A. (2002). "Tattooing the Body, Marking Culture". Body & Society. 8 (4): 91–107. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.602.5897. doi:10.1177/1357034x02008004005. S2CID 145369916.

- Gell, Alfred (1993) Wrapping in Images: Tattooing in Polynesia, Oxford: Clarendon Press

- Gilbert, Stephen G. (2001) Tattoo History: a Source Book, New York: Juno Books

- Gustafson, Mark (1997) "Inscripta in fronte: Penal Tattooing in Late Antiquity", in Classical Antiquity, April 1997, Vol. 16/No. 1, pp. 79–105

- Hambly, Wilfrid Dyson (1925) The History of Tattooing and Its Significance: With Some Account of Other Forms of Corporal Marking, London: H. F. & G. Witherby (reissued: Detroit 1974)

- Hesselt van Dinter, Maarten (2005) The World of Tattoo; An Illustrated History. Amsterdam, KIT Publishers

- Jones, C. P. (1987) "Stigma: Tattooing and Branding in Graeco–Roman Antiquity", in Journal of Roman Studies, 77/1987, pp. 139–155

- Juno, Andrea. Modern Primitives. Re/Search #12 (October 1989) ISBN 0-9650469-3-1

- Kächelen, Wolf-Peter (2004): Tatau und Tattoo – Eine Epigraphik der Identitätskonstruktion. Shaker Verlag, Aachen, ISBN 3-8322-2574-9.

- Kächelen, Wolf-Peter (2020): "Tatau und Tattoo Revisited: Tattoo pandemic: A forerunner of globel economic and social collapse." In: Wolf-Peter Kächelen - Tatau und Tattoo

- Lombroso, Cesare (1896) "The Savage Origin of Tattooing", in Popular Science Monthly, Popular Science Vol. IV., 1896

- Pang, Joey (2008) "Tattoo Art Expressions"

- Raviv, Shaun (2006) "Marked for Life: Jews and Tattoos" (Moment Magazine; June 2006)

- "Comparative study about Ötzi's therapeutic tattoos" (L. Renaut, 2004, French and English abstract)

- Robley, Horatio (1896) Moko, or, Maori tattooing. London: Chapman and Hall

- Roth, H. Ling (1901) "Maori tatu and moko". In: Journal of the Anthropological Institute vol. 31, January–June 1901

- Rubin, Arnold (ed.) (1988) Marks of Civilization: Artistic Transformations of the Human Body, Los Angeles: UCLA Museum of Cultural History

- Sanders, Clinton R. (1989) Customizing the Body: the Art and Culture of Tattooing. Philadelphia: Temple University Press

- Sinclair, A. T. (1909) "Tattooing of the North American Indians", in American Anthropologist 1909/11, No. 3, p. 362–400

- Thompson, Beverly Yuen (2015) Covered in Ink: Tattoos, Women and the Politics of the Body Archived 27 September 2018 at the Wayback Machine, New York University Press. ISBN 9780814789209

- Wianecki, Shannon (2011) "Marked" Maui No Ka 'Oi Magazine.

- Popular and artistic

- Green, Terisa. Ink: The Not-Just-Skin-Deep Guide to Getting a Tattoo New York: New American Library ISBN 0-451-21514-1

- Green, Terisa. The Tattoo Encyclopedia: A Guide to Choosing Your Tattoo New York: New American Library ISBN 0-7432-2329-2

- Kraków, Amy. Total Tattoo Book New York: Warner Books ISBN 0-446-67001-4

- Medical

- CDC's Position on Tattooing and HCV Infection, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, retrieved 12 June 2006

- Body Art (workplace hazards), National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health, retrieved 15 September 2008

- "Tattoos and Permanent Makeup", CFSAN/Office of Cosmetics and Colors (2000; updated 2004, 2006), United States Food and Drug Administration, retrieved 12 June 2006

- Haley, R. W.; Fischer, R. P. (March 2000). "Commercial tattooing as a potential source of hepatitis C infection". Medicine. 80 (2): 134–151. doi:10.1097/00005792-200103000-00006. PMID 11307589. S2CID 42897920.

- Paola Piccinini, Laura Contor, Ivana Bianchi, Chiara Senaldi, Sazan Pakalin: Safety of tattoos and permanent make-up, Joint Research Centre, 2016, ISBN 978-92-79-58783-2, doi:10.2788/011817.

Further reading

| Library resources about Tattoo |

- van Dinter, Maarten Hesselt (2000). Tribal tattoo designs (Hardcover). Amsterdam: Pepin Press. ISBN 9789054960737.

External links

- Tattoos, The Permanent Art, documentary produced by Off Book

- History, Ink produced by Meghan Glass Hughes for The Valentine Richmond History Center