Siemens

Siemens AG (German pronunciation: [ˈziːməns] (![]() listen)[4][5][6] or [-mɛns][6]) is a German multinational conglomerate corporation and the largest industrial manufacturing company in Europe[7] headquartered in Munich with branch offices abroad.

listen)[4][5][6] or [-mɛns][6]) is a German multinational conglomerate corporation and the largest industrial manufacturing company in Europe[7] headquartered in Munich with branch offices abroad.

Headquarters | |

| Type | Public |

|---|---|

Traded as | FWB: SIE DAX component |

| ISIN | DE0007236101 |

| Industry | Conglomerate |

| Predecessors | A. Reyrolle & Company Siemens-Schuckert Siemens-Reiniger-Werke |

| Founded | 1 October 1847 Berlin, Kingdom of Prussia |

| Founder | Werner von Siemens |

| Headquarters | Munich and Berlin, Germany[1] |

Area served | Worldwide |

Key people | Jim Hagemann Snabe (Chairman) Roland Busch (CEO) |

| Products | Electric generators, Transformers, Industrial and buildings automation, Medical equipment, Rolling stock, Water treatment systems, Fire alarms, PLM software, Marine engines, Diesel and gas engines, Electric motors, Pumps, Compressors, Gas turbines, Steam turbines, Industrial machines, Home appliances, Telecommunications equipment |

| Services | Business services, financing, project engineering and construction |

| Revenue | |

| Total assets | |

| Total equity | |

| Owner | Siemens family (6.9%) |

Number of employees | 303,000 (2021)[2] |

| Divisions |

|

| Website | www |

The principal divisions of the corporation are Industry, Energy, Healthcare (Siemens Healthineers), and Infrastructure & Cities, which represent the main activities of the corporation.[8][9][10] The corporation is a prominent maker of medical diagnostics equipment and its medical health-care division, which generates about 12 percent of the corporation's total sales, is its second-most profitable unit, after the industrial automation division. The corporation is a component of the Euro Stoxx 50 stock market index.[11] Siemens and its subsidiaries employ approximately 303,000 people worldwide and reported global revenue of around €62 billion in 2021[2] according to its earnings release.

History

1847 to 1901

Siemens & Halske was founded by Werner von Siemens and Johann Georg Halske on 1 October 1847. Based on the telegraph, their invention used a needle to point to the sequence of letters, instead of using Morse code. The company, then called Telegraphen-Bauanstalt von Siemens & Halske, opened its first workshop on 12 October.[12]

In 1848, the company built the first long-distance telegraph line in Europe; 500 km from Berlin to Frankfurt am Main. In 1850, the founder's younger brother, Carl Wilhelm Siemens, later Sir William Siemens, started to represent the company in London. The London agency became a branch office in 1858. In the 1850s, the company was involved in building long-distance telegraph networks in Russia. In 1855, a company branch headed by another brother, Carl Heinrich von Siemens, opened in St Petersburg, Russia. In 1867, Siemens completed the monumental Indo-European telegraph line stretching over 11,000 km from London to Calcutta.[13]

In 1867, Werner von Siemens described a dynamo without permanent magnets.[14] A similar system was also independently invented by Ányos Jedlik and Charles Wheatstone, but Siemens became the first company to build such devices. In 1881, a Siemens AC Alternator driven by a watermill was used to power the world's first electric street lighting in the town of Godalming, United Kingdom. The company continued to grow and diversified into electric trains and light bulbs. In 1885, Siemens sold one of its generators to George Westinghouse, thereby enabling Westinghouse to begin experimenting with AC networks in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania.

In 1887, Siemens opened its first office in Japan.[15] In 1890, the founder retired and left the running of the company to his brother Carl and sons Arnold and Wilhelm. In 1892, Siemens were contracted to construct the Hobart electric tramway in Tasmania, Australia as they increased their markets. The system opened in 1893 and became the first complete electric tram network in the Southern Hemisphere.[16]

1901 to 1933

Siemens & Halske (S & H) was incorporated in 1897, and then merged parts of its activities with Schuckert & Co., Nuremberg in 1903 to become Siemens-Schuckert. In 1907, Siemens (Siemens & Halske and Siemens-Schuckert) had 34,324 employees and was the seventh-largest company in the German empire by number of employees.[17] (see List of German companies by employees in 1907)

In 1919, S & H and two other companies jointly formed the Osram lightbulb company.[18]

During the 1920s and 1930s, S & H started to manufacture radios, television sets, and electron microscopes.[19]

In 1932, Reiniger, Gebbert & Schall (Erlangen), Phönix AG (Rudolstadt) and Siemens-Reiniger-Veifa mbH (Berlin) merged to form the Siemens-Reiniger-Werke AG (SRW), the third of the so-called parent companies that merged in 1966 to form the present-day Siemens AG.[20]

In the 1920s, Siemens constructed the Ardnacrusha Hydro Power station on the River Shannon in the then Irish Free State, and it was a world first for its design. The company is remembered for its desire to raise the wages of its under-paid workers only to be overruled by the Cumann na nGaedheal government.[21]

1933 to 1945

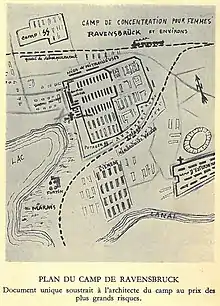

Siemens (at the time: Siemens-Schuckert) exploited the forced labour of deported people in extermination camps. The company owned a plant in Auschwitz concentration camp.[22][23]

Siemens exploited the forced labour of women in the concentration camp of Ravensbrück. The factory was located in front of the camp.[24]

During the final years of World War II, numerous plants and factories in Berlin and other major cities were destroyed by Allied air raids. To prevent further losses, manufacturing was therefore moved to alternative places and regions not affected by the air war. The goal was to secure continued production of important war-related and everyday goods. According to records, Siemens was operating almost 400 alternative or relocated manufacturing plants at the end of 1944 and in early 1945.

In 1972, Siemens sued German satirist F.C. Delius for his satirical history of the company, Unsere Siemens-Welt, and it was determined much of the book contained false claims although the trial itself publicized Siemens' history in Nazi Germany.[25] The company supplied electrical parts to Nazi concentration camps and death camps. The factories had poor working conditions, where malnutrition and death were common. Also, the scholarship has shown that the camp factories were created, run, and supplied by the SS, in conjunction with company officials, sometimes high-level officials.[26][27][28][29]

1945 to 2001

In the 1950s, and from their new base in Bavaria, S&H started to manufacture computers, semiconductor devices, washing machines, and pacemakers. In 1966, Siemens & Halske (S&H, founded in 1847), Siemens-Schuckertwerke (SSW, founded in 1903) and Siemens-Reiniger-Werke (SRW, founded in 1932) merged to form Siemens AG.[30] In 1969, Siemens formed Kraftwerk Union with AEG by pooling their nuclear power businesses.[31]

The company's first digital telephone exchange was produced in 1980, and in 1988, Siemens and GEC acquired the UK defence and technology company Plessey. Plessey's holdings were split, and Siemens took over the avionics, radar and traffic control businesses—as Siemens Plessey.[32]

In 1977, Advanced Micro Devices (AMD) entered into a joint venture with Siemens, which wanted to enhance its technology expertise and enter the American market.[33] Siemens purchased 20% of AMD's stock, giving the company an infusion of cash to increase its product lines.[33][34][35] The two companies also jointly established Advanced Micro Computers (AMC), located in Silicon Valley and in Germany, allowing AMD to enter the microcomputer development and manufacturing field,[33][36][37][38] in particular based on AMD's second-source Zilog Z8000 microprocessors.[39][40] When the two companies' vision for Advanced Micro Computers diverged, AMD bought out Siemens' stake in the American division in 1979.[41][42] AMD closed Advanced Micro Computers in late 1981 after switching focus to manufacturing second-source Intel x86 microprocessors.[39][43][44]

In 1985, Siemens bought Allis-Chalmers' interest in the partnership company Siemens-Allis (formed 1978) which supplied electrical control equipment. It was incorporated into Siemens' Energy and Automation division.[45]

In 1987, Siemens reintegrated Kraftwerk Union, the unit overseeing nuclear power business.[31]

In 1989, Siemens bought the solar photovoltaic business, including 3 solar module manufacturing plants, from industry pioneer ARCO Solar, owned by oil firm ARCO.[46]

In 1991, Siemens acquired Nixdorf Computer AG and renamed it Siemens Nixdorf Informationssysteme AG, in order to produce personal computers.[47]

In October 1991, Siemens acquired the Industrial Systems Division of Texas Instruments, Inc, based in Johnson City, Tennessee. This division was organized as Siemens Industrial Automation, Inc.,[48] and was later absorbed by Siemens Energy and Automation, Inc.

In 1992, Siemens bought out IBM's half of ROLM (Siemens had bought into ROLM five years earlier), thus creating SiemensROLM Communications; eventually dropping ROLM from the name later in the 1990s.[49]

In 1993–1994, Siemens C651 electric trains for Singapore's Mass Rapid Transit (MRT) system were built in Austria.

In 1997, Siemens agreed to sell the defence arm of Siemens Plessey to British Aerospace (BAe) and a German aerospace company, DaimlerChrysler Aerospace. BAe and DASA acquired the British and German divisions of the operation respectively.[50]

In October 1997, Siemens Financial Services (SFS) was founded to act as a competence center for financing issues and as a manager of financial risks within Siemens.

In 1998, Siemens acquired Westinghouse Power Generation for more than $1.5 billion from the CBS Corporation and moving Siemens from third to second in the world power generation market.[51]

In 1999, Siemens' semiconductor operations were spun off into a new company called Infineon Technologies. Its Electromechanical Components operations were converted into a legally independent company: Siemens Electromechanical Components GmbH & Co. KG, (which, later that year, was sold to Tyco International Ltd for approximately $1.1 billion.[52]

In the same year, Siemens Nixdorf Informationssysteme AG became part of Fujitsu Siemens Computers AG, with its retail banking technology group becoming Wincor Nixdorf.[47]

In 2000, Shared Medical Systems Corporation[53] was acquired by the Siemens' Medical Engineering Group,[54] eventually becoming part of Siemens Medical Solutions.

Also in 2000, Atecs-Mannesman was acquired by Siemens,[55] The sale was finalised in April 2001 with 50% of the shares acquired, acquisition, Mannesmann VDO AG merged into Siemens Automotive forming Siemens VDO Automotive AG, Atecs Mannesmann Dematic Systems merged into Siemens Production and Logistics forming Siemens Dematic AG, Mannesmann Demag Delaval merged into the Power Generation division of Siemens AG.[56] Other parts of the company were acquired by Robert Bosch GmbH at the same time.[57] Also, Moore Products Co. of Spring House, PA USA was acquired by Siemens Energy & Automation, Inc.[58]

2001 to 2005

In 2001, Chemtech Group of Brazil was incorporated into the Siemens Group;[59] it provides industrial process optimisation, consultancy and other engineering services.[60]

Also in 2001, Siemens formed joint venture Framatome with Areva SA of France by merging much of the companies' nuclear businesses.[31]

In 2002, Siemens sold some of its business activities to Kohlberg Kravis Roberts & Co. L.P. (KKR), with its metering business included in the sale package.[61]

In 2002, Siemens abandoned the solar photovoltaic industry by selling its participation in a joint-venture company, established in 2001 with Shell and E.ON, to Shell.[62]

In 2003, Siemens acquired the flow division of Danfoss and incorporated it into the Automation and Drives division.[63] Also in 2003 Siemens acquired IndX software (realtime data organisation and presentation).[64][65] The same year in an unrelated development Siemens reopened its office in Kabul.[66] Also in 2003 agreed to buy Alstom Industrial Turbines; a manufacturer of small, medium and industrial gas turbines for €1.1 billion.[67][68] On 11 February 2003, Siemens planned to shorten phones' shelf life by bringing out annual Xelibri lines, with new devices launched as spring -summer and autumn-winter collections.[69] On 6 March 2003, the company opened an office in San Jose.[70] On 7 March 2003, the company announced that it planned to gain 10 per cent of the mainland China market for handsets.[71] On 18 March 2003, the company unveiled the latest in its series of Xelibri fashion phones.[72]

In 2004, the wind energy company Bonus Energy in Brande, Denmark was acquired,[73][74] forming Siemens Wind Power division.[75] Also in 2004 Siemens invested in Dasan Networks (South Korea, broadband network equipment) acquiring ~40% of the shares,[76] Nokia Siemens disinvested itself of the shares in 2008.[77] The same year Siemens acquired Photo-Scan (UK, CCTV systems),[78] US Filter Corporation (water and Waste Water Treatment Technologies/ Solutions, acquired from Veolia),[79] Hunstville Electronics Corporation (automobile electronics, acquired from Chrysler),[80] and Chantry Networks (WLAN equipment).[81]

In 2005, Siemens sold the Siemens mobile manufacturing business to BenQ, forming the BenQ-Siemens division. Also in 2005 Siemens acquired Flender Holding GmbH (Bocholt, Germany, gears/industrial drives),[82] Bewator AB (building security systems),[83] Wheelabrator Air Pollution Control, Inc. (Industrial and power station dust control systems),[84] AN Windenergie GmbH. (Wind energy),[85] Power Technologies Inc. (Schenectady, USA, energy industry software and training),[86] CTI Molecular Imaging (Positron emission tomography and molecular imaging systems),[87][88] Myrio (IPTV systems), Shaw Power Technologies International Ltd (UK/USA, electrical engineering consulting, acquired from Shaw Group),[89][90] and Transmitton (Ashby de la Zouch UK, rail and other industry control and asset management).[91]

2005 and continuing: worldwide bribery scandal

Beginning in 2005, Siemens became embroiled in a multi-national bribery scandal.[92] One component of this scandal was the Siemens Greek bribery scandal over deals between Siemens and Greek government officials during the 2004 Summer Olympic Games.[93] Siemens' activities came under legal scrutiny when complaints from prosecutors in Italy, Liechtenstein and Switzerland lead to German authorities opening investigations, followed by a US investigation in 2006 concerning their activities while listed on US stock exchanges.[94] The investigators found that bribing officials to win contracts was standard operating procedure.[94][95] Over that time period the company paid around $1.3 billion in bribes in many countries and kept separate books to hide them.[95] Settlement negotiations took place through most of 2008 with settlement terms announced in December 2008. The company paid a total of about $1.6 billion, around $800 million to the US and Germany each. This was the largest bribery fine in history, at the time. The company was also obligated to spend $1 billion on setting up and funding new internal compliance regimens.[94] Siemens pleaded guilty to violating accounting provisions of the Foreign Corrupt Practices Act; the parent company did not plead guilty to paying bribes (although its Bangladesh and Venezuela subsidiaries did[95]).

In 2005 Germany opened investigations into Siemens business practices worldwide, prompted by requests from prosecutors in Italy, Liechtenstein and Switzerland; US investigators joined in 2006 and the US investigators addressed violations only since 2001, when Siemens started selling shares in a US stock exchange.[94] The investigators found that bribing officials to win contracts was standard operating procedure.[94][95] Over that time period the company paid around $1.3 billion in bribes in many countries and kept separate books to hide them.[95]

Fines were anticipated to be as high as $5 billion as the investigation unfolded.[96] Settlement negotiations took place through most of 2008 and when they were announced in December they were far less, driven in part by Siemens' cooperation, in part by the imminent change in US administrations (the Obama administration was about to take over from the Bush administration), and in part by the dependence of the US military on Siemens as a contractor.[94][96][95]

The company paid a total of about $1.6 billion, around $800 million in each of the US and Germany. This was the largest bribery fine in history, at the time. The money paid to Germany included a $270 million fine paid the year before (related to bribes in Nigeria[97]). The US payment included $450 million in fines and penalties and a forfeiture of $350 million in profits.[95] The company was also obligated to spend $1 billion on setting up and funding new internal compliance regimens.[94] Siemens pleaded guilty to violating accounting provisions of the Foreign Corrupt Practices Act; the parent company did not plead guilty to paying bribes (although its Bangladesh and Venezuela subsidiaries did[95]); such a guilty plea would have barred Siemens from contracting for the US government.[94] As the scandal had started breaking, Siemens had fired its chairman and CEO Heinrich von Pierer, and had hired its first non-German CEO, Peter Löscher; it also had appointed a US lawyer, Peter Solmssen as an independent director to its board, in charge of compliance, and had accepted oversight of Theo Waigel, a former German finance minister, as a "compliance monitor".[96] The compliance overhaul eventually entailed hiring around 500 full-time compliance personnel worldwide. Siemens also enacted a series of new anti-corruption compliance policies, including a new anti-corruption handbook, web-based tools for due diligence and compliance, a confidential communications channel for employees to report irregular business practices, and a corporate disciplinary committee to impose appropriate disciplinary measures for substantiated misconduct.[98]

The culture of bribery was old in Siemens, and led to the 1914 scandal in Japan over bribes paid by both Siemens and Vickers to Japanese naval authorities to win shipbuilding contracts.[99]

The culture of bribery developed further within Siemens after World War II as it attempted to rebuild its business by competing in the developing world, where bribery is common. Until 1999 in Germany, bribes were a tax-deductible business expense, and there were no penalties for bribing foreign officials. In 1999 the OECD Anti-Bribery Convention came into effect, to which Germany was a party, and Siemens started to use off-shore accounts and other means of hiding its bribery.

As the investigation opened a midlevel executive in the telecommunications unit, Reinhard Siekaczek, was identified as a key player; Siekaczek quit Siemens in 2005 after the company required him to sign a document saying he had followed law and company policy, and turned state's evidence and led investigators to documents he had saved and to other documents. He had controlled an annual global bribery budget of $40 to $50 million. The usual method of bribery was to pay a local insider as a "contractor" who would in turn pass money to government officials; as part of the settlement Siemens disclosed that it had 2,700 such contractors worldwide. Bribes were generally around 5% of a contract's value but in very corrupt countries they could be as high as 40%. It paid the highest bribes in Argentina, Israel, Venezuela, China, Nigeria, and Russia.[94]

Examples of bribery the investigation found included:[94]

- $40 million in bribes in Argentina to win a $1 billion contract to make national identity cards.

- $20 million in Israel for a contract to build power plants

- $16 million in Venezuela for urban rail lines.

- $14 million In China for medical equipment

- $12.7 million in payments in Nigeria

- $5 million in Bangladesh for mobile phones

- $1.7 million in Iraq to Saddam Hussein and others.

The investigation led directly to several prosecutions while it was unfolding, and led to settlements with other governments and prosecution of Siemens employees and bribe recipients in various countries.

In May 2007 a German court convicted two former executives of paying about €6 million in bribes from 1999 to 2002 to help Siemens win natural gas turbine supply contracts with Enel, an Italian energy company. The contracts were valued at about €450 million. Siemens was fined €38 million.[100]

In July 2009, Siemens settled allegations of fraud by a Russian affiliate in a World Bank-funded mass transit project in Moscow by agreeing to not bid on World Bank projects for two years, not allowing the Russian affiliate to do any World Bank funded work for four years, and setting up a $100 million fund at the World Bank to fund anti-corruption activities over 15 years, over which the World Bank had veto and audit rights; this fund became the "Siemens Integrity Initiative".[101][102] The first payments were made out of the funds in 2010 in a tranche of $40 million.[103] A second set of projects was funded in 2014 totaling $30 million.[104]

Siemens paid N7 billion to the Nigerian government in 2010.[105]

In 2012, the Greek government settled the Greek bribery scandal for 330 million euros.[106] The trial of the persons accused of involvement in the scandal began on 24 February 2017. A total of 64 individuals are accused, both Greek and German nationals.[107] The central figure of the scandal however, ex-Siemens chief executive in Greece Michael Christoforakos, against whom European arrest warrants are pending[108][109] will likely be absent, as Germany refuses his extradition to this day. Initially arrested in Germany in 2009, the accusations against him by German courts have been dropped, and he since lives free in this country.[110][111] Greece has been demanding his extradition since 2009, and considers him a fugitive from justice.

In 2014 a former Siemens executive Andres Truppel pleaded guilty to funneling nearly $100 million in bribes to Argentine government officials to win the ID card project for Siemens.[112]

In 2014 Israeli prosecutors decreed that Siemens should pay US$42.7 million penalty and appoint an external inspector to supervise its business in Israel in exchange for state prosecutors dropping charges of securities fraud. According to the indictment, "Siemens systematically paid bribes to Israel Electric Corporation executives so they would utilize their positions in order to favor and advance the interests of Siemens".[112]

2006 to 2011

In 2006, Siemens purchased Bayer Diagnostics which was incorporated into the Medical Solutions Diagnostics division on 1 January 2007,[113] also in 2006 Siemens acquired Controlotron (New York) (ultrasonic flow meters),[114][115] and also in 2006 Siemens acquired Diagnostic Products Corp., Kadon Electro Mechanical Services Ltd. (now TurboCare Canada Ltd.), Kühnle, Kopp, & Kausch AG, Opto Control, and VistaScape Security Systems.[116]

In January 2007, Siemens was fined €396 million by the European Commission for price fixing in EU electricity markets through a cartel involving 11 companies, including ABB, Alstom, Fuji Electric, Hitachi Japan, AE Power Systems, Mitsubishi Electric Corp, Schneider, Areva, Toshiba and VA Tech.[117] According to the commission, "between 1988 and 2004, the companies rigged bids for procurement contracts, fixed prices, allocated projects to each other, shared markets and exchanged commercially important and confidential information."[117] Siemens was given the highest fine of €396 million, more than half of the total, for its alleged leadership role in the activity.

In March 2007, a Siemens board member was temporarily arrested and accused of illegally financing a business-friendly labour association which competes against the union IG Metall. He has been released on bail. Offices of the labour union and of Siemens have been searched. Siemens denies any wrongdoing.[118] In April the Fixed Networks, Mobile Networks and Carrier Services divisions of Siemens merged with Nokia's Network Business Group in a 50/50 joint venture, creating a fixed and mobile network company called Nokia Siemens Networks. Nokia delayed the merger[119] due to bribery investigations against Siemens.[120] In October 2007, a court in Munich found that the company had bribed public officials in Libya, Russia, and Nigeria in return for the awarding of contracts; four former Nigerian Ministers of Communications were among those named as recipients of the payments. The company admitted to having paid the bribes and agreed to pay a fine of 201 million euros. In December 2007, the Nigerian government cancelled a contract with Siemens due to the bribery findings.[121][122]

Also in 2007, Siemens acquired Vai Ingdesi Automation (Argentina, Industrial Automation), UGS Corp., Dade Behring, Sidelco (Quebec, Canada), S/D Engineers Inc., and Gesellschaft für Systemforschung und Dienstleistungen im Gesundheitswesen mbH (GSD) (Germany).[123]

In July 2008, Siemens AG formed a joint venture of the Enterprise Communications business with the Gores Group, renamed Unify in 2013. The Gores Group holding a majority interest of 51% stake, with Siemens AG holding a minority interest of 49%.[124]

In August 2008, Siemens Project Ventures invested $15 million in the Arava Power Company. In a press release published that month, Peter Löscher, President and CEO of Siemens AG said: "This investment is another consequential step in further strengthening our green and sustainable technologies". Siemens now holds a 40% stake in the company.[125]

In January 2009, Siemens sold its 34% stake in Framatome, complaining limited managerial influence. In March, it formed an alliance with Rosatom of Russia to engage in nuclear-power activities.[31]

In April 2009, Fujitsu Siemens Computers became Fujitsu Technology Solutions as a result of Fujitsu buying out Siemens' share of the company.

In June 2009 news broke that Nokia Siemens had supplied telecommunications equipment to the Iranian telecom company that included the ability to intercept and monitor telecommunications, a facility known as "lawful intercept". The equipment was believed to have been used in the suppression of the 2009 Iranian election protests, leading to criticism of the company, including by the European Parliament. Nokia Siemens later divested its call monitoring business, and reduced its activities in Iran.[126][127][128][129][130][131]

In October 2009, Siemens signed a $418 million contract to buy Solel Solar Systems, an Israeli company in the solar thermal power business.[132]

In December 2010, Siemens agreed to sell its IT Solutions and Services subsidiary for €850 million to Atos. As part of the deal, Siemens agreed to take a 15% stake in the enlarged Atos, to be held for a minimum of five years. In addition, Siemens concluded a seven-year outsourcing contract worth around €5.5 billion, under which Atos will provide managed services and systems integration to Siemens.

2011 to present

In March 2011, it was decided to list Osram on the stock market in the autumn, but CEO Peter Löscher said Siemens intended to retain a long-term interest in the company, which was already independent from the technological and managerial viewpoints.

In September 2011, Siemens, which had been responsible for constructing all 17 of Germany's existing nuclear power plants, announced that it would exit the nuclear sector following the Fukushima disaster and the subsequent changes to German energy policy. Chief executive Peter Löscher has supported the German government's planned Energiewende, its transition to renewable energy technologies, calling it a "project of the century" and saying Berlin's target of reaching 35% renewable energy sources by 2020 was feasible.[133]

In November 2012, Siemens acquired the Rail division of Invensys for £1.7 billion. In the same month, Siemens acquired a privately held company, LMS International NV.[134]

In August 2013, Nokia acquired 100% of the company Nokia Siemens Networks, with a buy-out of Siemens AG, ending Siemens role in telecommunication.[135]

In August 2013, Siemens won a $966.8 million order for power plant components from oil firm Saudi Aramco, the largest bid it has ever received from the Saudi company.[136]

In 2014, Siemens announced plans to build a $264 million facility for making offshore wind turbines in Paull, England, as Britain's wind power rapidly expands. Siemens chose the Hull area on the east coast of England because it is close to other large offshore projects planned in coming years. The new plant is expected to begin producing turbine rotor blades in 2016. The plant and the associated service center, in Green Port Hull nearby, will employ about 1,000 workers. The facilities will serve the UK market, where the electricity that major power producers generate from wind grew by about 38 percent in 2013, representing about 6 percent of total electricity, according to government figures. There are also plans to increase Britain's wind-generating capacity at least threefold by 2020, to 14 gigawatts.[137]

In May 2014, Rolls-Royce agreed to sell its gas turbine and compressor energy business to Siemens for £1 billion.[138]

In June 2014, Siemens and Mitsubishi Heavy Industries announced their formation of joint ventures to bid for Alstom's troubled energy and transportation businesses (in locomotives, steam turbines, and aircraft engines). A rival bid by General Electric (GE) has been criticized by French government sources, who consider Alstom's operations as a "vital national interest" at a moment when the French unemployment level stands above 10% and some voters are turning towards the far-right.[139]

In 2015, Siemens acquired U.S. oilfield equipment maker Dresser-Rand Group Inc for $7.6 billion.[140][141]

In November 2016, Siemens acquired EDA company Mentor Graphics for $4.5 billion.[142]

In November 2017, the U.S. Department of Justice charged three Chinese employees of Guangzhou Bo Yu Information Technology Company Limited with hacking into corporate entities, including Siemens AG.[143]

In December 2017, Siemens acquired the medical technology company Fast Track Diagnostics for an undisclosed amount.[144]

In August 2018, Siemens acquired rapid application development company Mendix for €0.6 billion in cash.[145]

In May 2018, Siemens acquired J2 Innovations for an undisclosed amount.[146][147]

In May 2018, Siemens acquired Enlighted, Inc. for an undisclosed amount.[148]

In September 2019, Siemens and Orascom Construction signed an agreement with the Iraqi government to rebuild two power plants, which is believed to setup the company for future deals in the country.[149]

In 2019–2020, Siemens was identified as a key engineering company supporting the controversial[150] Adani Carmichael coal mine in Queensland (Australia).[151]

In January 2020, Siemens signed an agreement to acquire 99% equity share capital of Indian switchgear manufacturer C&S Electric at €267 million (₹2,100 crore).[152] The takeover was approved by the Competition Commission of India in August 2020.[153]

In April 2020, Siemens acquired a 77% majority stake in Indian building solution provider iMetrex Technologies for an undisclosed sum.[154]

In April 2020, Siemens Energy was created as an independent company out of the energy division of Siemens.[155] The trading of shares of the new Siemens Energy AG on the stock exchange is expected to be possible from 28 September onwards.[156]

In August 2020, Siemens Healthineers AG announced that it plans to acquire U.S. cancer device and software company Varian Medical Systems in an all-stock deal valued at $16.4 billion.[157]

In October 2021, Siemens acquired the building IoT software and hardware company Wattsense for an undisclosed sum.[158]

In May 2022, Siemens decided to drop Russian operations and everything regarding the conglomerate on the Russian state amid the ongoing war of aggression against Ukraine since February 24th. In July 2022, Siemens acquired ZONA Technology, specialist in aerospace simulation firm. [159]

Products, services and contribution

Siemens offers a wide range of electrical engineering- and electronics-related products and services.[160] Its products can be broadly divided into the following categories: buildings-related products; drives, automation and industrial plant-related products; energy-related products; lighting; medical products; and transportation and logistics-related products.[160]

Siemens buildings-related products include building-automation equipment and systems; building-operations equipment and systems; building fire-safety equipment and systems; building-security equipment and systems; and low-voltage switchgear including circuit protection and distribution products.[160]

Siemens drives, automation and industrial plant-related products include motors and drives for conveyor belts; pumps and compressors; heavy duty motors and drives for rolling steel mills; compressors for oil and gas pipelines; mechanical components including gears for wind turbines and cement mills; automation equipment and systems and controls for production machinery and machine tools; and industrial plant for water processing and raw material processing.[160]

Siemens energy-related products include gas and steam turbines; generators; compressors; on- and offshore wind turbines; high-voltage transmission products; power transformers; high-voltage switching products and systems; alternating and direct current transmission systems; medium-voltage components and systems; and power automation products.[160]

In the renewable energy industry, the company provides a portfolio of products and services to help build and operate microgrids of any size. It provides generation and distribution of electrical energy as well as monitoring and controlling of microgrids.[161] By using primarily renewable energy, microgrids reduce carbon-dioxide emissions, which is often required by government regulations. It supplied a sustainable storage produc and s microgrid to Enel Produzione SPA for the island of Ventotene in Italy.[161]

Siemens medical products include clinical information technology systems; hearing instruments; in-vitro diagnostics equipment; imaging equipment including angiography, computed tomography, fluoroscopy, magnetic resonance, mammography, molecular imaging ultrasound, and x-ray equipment; and radiation oncology and particle therapy equipment.[160] As of 2015, Siemens finalized the sale of its hearing-aid (hearing instruments) business to Sivantos.[162][163]

Siemens transportation and logistics-related products include equipment and systems for rail transportation including rail vehicles for mass transit, regional and long-distance transportation, locomotives, equipment and systems for rail electrification, central control systems, interlockings, and automated train controls; equipment and systems for road traffic including traffic detection, information and guidance; equipment and systems for airport logistics including cargo tracking and baggage handling; and equipment and systems for postal automation including letter parcel sorting.[160]

A Siemens high-voltage transformer

A Siemens high-voltage transformer A Siemens SPECT/CT scanner in operation

A Siemens SPECT/CT scanner in operation A Siemens wind power generator

A Siemens wind power generator A Siemens steam turbine rotor

A Siemens steam turbine rotor A Siemens train in operation

A Siemens train in operation Bangkok Skytrain built by Siemens

Bangkok Skytrain built by Siemens

Operations

Siemens is incorporated in Germany and has its corporate headquarters in Munich.[164] As of 2011, has operations in around 190 countries and approximately 285 production and manufacturing facilities.[164] Siemens had around 360,000 employees as of 30 September 2011.[164]

Research and development

In 2011, Siemens invested a total of €3.925 billion in research and development, equivalent to 5.3% of revenues.[164] As of 30 September 2011, Siemens had approximately 11,800 Germany-based employees engaged in research and development and approximately 16,000 in the rest of the world, of whom the majority were based in either Austria, China, Croatia, Denmark, France, India, Japan, Mexico, The Netherlands, Russia, Slovakia, Sweden, Switzerland, the United Kingdom or the United States.[164] As of 30 September 2011, Siemens held approximately 53,300 patents worldwide.[164]

Siemens' headquarters, Munich (front)

Siemens' headquarters, Munich (front) Siemens office building in Munich-Giesing

Siemens office building in Munich-Giesing Siemens-Tower in Berlin-Siemensstadt

Siemens-Tower in Berlin-Siemensstadt "Wernerwerk" (Werner's Factory) in Berlin-Siemensstadt

"Wernerwerk" (Werner's Factory) in Berlin-Siemensstadt Wernerwerk II in Berlin-Siemensstadt

Wernerwerk II in Berlin-Siemensstadt_Berlin-Siemensstadt_002.jpg.webp) Wernerwerk XV in Berlin-Siemensstadt

Wernerwerk XV in Berlin-Siemensstadt Siemens office building in Erlangen

Siemens office building in Erlangen Siemens office building in Erlangen

Siemens office building in Erlangen Siemens site in Munich-Perlach

Siemens site in Munich-Perlach Siemens Forum Munich

Siemens Forum Munich Siemens Gas Turbine Factory, formerly Ruston & Hornsby Pelham Works, Lincoln, England

Siemens Gas Turbine Factory, formerly Ruston & Hornsby Pelham Works, Lincoln, England

Joint ventures

Siemens' current joint ventures include:

- Siemens Traction Equipment Ltd. (STEZ), Zhuzhou China, is a joint venture between Siemens, Zhuzhou CSR Times Electric Co., Ltd. (TEC) and CSR Zhuzhou Electric Locomotive Co., Ltd. (ZELC), which produces AC drive electric locomotives and AC locomotive traction components.[165]

- Primetals Technologies a joint venture between Siemens VAI Metals Technologies and Mitsubishi Hitachi Metals Machinery formed in 2015.

- OMNETRIC Group, A Siemens & Accenture company formed in 2014.[166]

Former joint ventures include:

- Silcar was a joint venture between Siemens Ltd and Thiess Services Pty Ltd until 2013. Silcar is a 3,000 person Australian organisation providing productivity and reliability for large scale and technically complex plant assets. Services include asset management, design, construction, operations and maintenance. Silcar operates across a range of industries and essential services including power generation, electrical distribution, manufacturing, mining and telecommunications. In July 2013, Thiess took full control.[167][168][169]

Finances

For the fiscal year 2017, Siemens reported earnings of EUR 6.046 billion, with an annual revenue of €83.049 billion, an increase of 4.3% over the previous fiscal cycle.[170] Siemens' shares traded at over US$58 per share, and its market capitalization was valued at US$95.3 billion in November 2018.[171] In November 2019, the company had higher fourth quarter earnings than expected, with adjusted earnings before interest, taxes, and amortization totaling €2.64 billion ($2.92 billion), but warned of a slowdown, especially in the car sector, next year.[7]

| Year | Revenue in bn. EUR |

Net income in bn. EUR |

Total Assets in bn. EUR |

Employees |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2013 | 75.882 | 4.284 | 101.936 | 362,000 |

| 2014 | 71.920 | 5.373 | 104.879 | 357,000 |

| 2015 | 75.636 | 7.282 | 120.348 | 348,000 |

| 2016 | 79.644 | 5.450 | 125.717 | 351,000 |

| 2017 | 83.049 | 6.046 | 133.804 | 372,000 |

| 2018 | 83.044 | 5.807 | 138.915 | 379,000 |

| 2019 | 86.849 | 5.174 | 150.248 | 385,000 |

| 2020* | 57.139 | 4.030 | 123.897 | 293,000 |

| 2021 | 62.265 | 6.161 | 139.608 | 295,000 |

* In 2020 Siemens Energy became an independent company

Shareholders

The company has issued 881,000,000 shares of common stock. The largest single shareholder continues to be the founding shareholder, the Siemens family, with a stake of 6.9%. 62% are held by institutional asset managers, the largest being two divisions of the world's largest asset manager BlackRock. 83.97% of the shares are considered public float, however including such strategic investors as the State of Qatar (DIC Company Ltd.) with 3.04%, the Government Pension Fund of Norway with 2.5% and Siemens AG itself with 3.04%. 19% are held by private investors, 13% by investors that are considered unidentifiable. 26% are owned by German investors, 21% by US investors, followed by the UK (11%), France (8%), Switzerland (8%) and a number of others (26%).[172]

Senior management

Chairmen of the Siemens-Schuckertwerke Managing Board (1903 to 1966)[173]

- Alfred Berliner (1903 to 1912)

- Carl Friedrich von Siemens (1912 to 1919)

- Otto Heinrich (1919 to 1920)

- Carl Köttgen (1920 to 1939)

- Rudolf Bingel (1939 to 1945)

- Wolf-Dietrich von Witzleben (1945 to 1949)

- Günther Scharowsky (1949 to 1951)

- Friedrich Bauer (1951 to 1962)

- Bernhard Plettner (1962 to 1966)

Chairmen of the Siemens & Halske / Siemens-Schuckertwerke Supervisory Board (1918 to 1966)[173]

- Wilhelm von Siemens (1918 to 1919)

- Carl Friedrich von Siemens (1919 to 1941)

- Hermann von Siemens (1941 to 1946)

- Friedrich Carl Siemens (1946 to 1948)

- Hermann von Siemens (1948 to 1956)

- Ernst von Siemens (1956 to 1966)

Chairmen of the Siemens AG Managing Board (1966 to present)[173]

- Hans Kerschbaum, Adolf Lohse, Bernhard Plettner (Presidency of the Managing Board) (1966 to 1967)

- Erwin Hachmann, Bernhard Plettner, Gerd Tacke (Presidency of the Managing Board) (1967 to 1968)

- Gerd Tacke (1968 to 1971)

- Bernhard Plettner (1971 to 1981)

- Karlheinz Kaske (1981 to 1992)

- Heinrich von Pierer (1992 to 2005)

- Klaus Kleinfeld (2005 to 2007)

- Peter Löscher (2007 to 2013)

- Joe Kaeser (2013 to 2021)

- Roland Busch (2021 to present)

Chairmen of the Siemens AG Supervisory Board (1966 to present)[173]

- Ernst von Siemens (1966 to 1971)

- Peter von Siemens (1971 to 1981)

- Bernhard Plettner (1981 to 1988)

- Heribald Närger (1988 to 1993)

- Hermann Franz (1993 to 1998)

- Karl-Hermann Baumann (1998 to 2005)

- Heinrich von Pierer (2005 to 2007)

- Gerhard Cromme (2007 to 2018)

- Jim Hagemann Snabe (2018 to present)

Managing Board (present day)[174][175]

- Roland Busch (CEO Siemens AG)

- Klaus Helmrich

- Cedrik Neike (CEO Digital Industries)

- Matthias Rebellius (CEO Smart Infrastructure)

- Ralf P. Thomas (CFO)

- Judith Wiese

See also

References

- "Corporate Information", Siemens Aktiengesellschaft.

- "Siemens Report for Fiscal 2021" (PDF). Siemens. Retrieved 30 January 2022.

- "Siemens Shares, Bonds & Rating | Investor Relations | Siemens Global". siemens.com Global Website. Retrieved 21 October 2022.

- Dudenredaktion; Kleiner, Stefan; Knöbl, Ralf (2015) [First published 1962]. Das Aussprachewörterbuch [The Pronunciation Dictionary] (in German) (7th ed.). Berlin: Dudenverlag. ISBN 978-3-411-04067-4.

- Krech, Eva-Maria; Stock, Eberhard; Hirschfeld, Ursula; Anders, Lutz Christian (2009). Deutsches Aussprachewörterbuch [German Pronunciation Dictionary] (in German). Berlin: Walter de Gruyter. ISBN 978-3-11-018202-6.

- Wells, John C. (2008). Longman Pronunciation Dictionary (3rd ed.). Longman. ISBN 9781405881180.

- Sachgau, Oliver (7 November 2019). "Siemens Quarterly Profit Surge Comes With Cautious Outlook". Bloomberg.com. Retrieved 7 November 2019.

- AuntMinnie.com. "Siemens Healthcare now known as Siemens Healthineers" Archived 4 June 2016 at the Wayback Machine, AuntMinnie.com, 4 May 2016. Retrieved on 12 May 2016.

- Reuters. "Siemens healthcare rebrands as 'Healthineers'" Archived 7 May 2016 at the Wayback Machine, Reuters, 4 May 2016. Retrieved on 12 May 2016.

- Siemens Corporate Website. "Siemens Healthcare Becomes Siemens Healthineers" Archived 8 May 2016 at the Wayback Machine, Siemens, 4 May 2016. Retrieved on 12 May 2016.

- Frankfurt Stock Exchange Archived 19 November 2015 at the Wayback Machine

- "The year is 1847 – How it all began", Siemens Historical Institute". Siemens AG. Archived from the original on 11 December 2020. Retrieved 27 October 2019.

- "Halfway around the world in 28 minutes – Indo-European Telegraph Line". Siemens Historical Institute. Archived from the original on 20 January 2008. Retrieved 12 January 2008.

- "Electrification of the world – Werner von Siemens and the dynamoelectric principle". Siemens Historical Institute. Archived from the original on 20 September 2020. Retrieved 5 June 2019.

- Siemens website 1 August 2012 – 125 Years Siemens in Japan (1887–2012) Archived 5 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine Retrieved on 12 August 2013

- "A Brief History of the Hobart Electric Trams". Hobart City Council. Archived from the original on 24 December 2003. Retrieved 13 June 2021.

- Fiedler, Martin (1999). "Die 100 größten Unternehmen in Deutschland – nach der Zahl ihrer Beschäftigten – 1907, 1938, 1973 und 1995". Zeitschrift für Unternehmensgeschichte (in German). Munich: Verlag C.H. Beck. 1: 32–66. doi:10.1515/zug-1999-0104. S2CID 165110552.

- "Shining bright – The interlinked history of Siemens and OSRAM". Siemens Historical Institute. Archived from the original on 30 September 2020. Retrieved 5 June 2019.

- Rudenberg, H Gunther; Rudenberg, Paul G (2010). "Chapter 6 – Origin and Background of the Invention of the Electron Microscope: Commentary and Expanded Notes on Memoir of Reinhold Rüdenberg". Advances in Imaging and Electron Physics. Vol. 160. Elsevier. doi:10.1016/S1076-5670(10)60006-7. ISBN 978-0-12-381017-5.

- "Setting the Course for the Future – The Founding of Siemens AG". Archived from the original on 25 October 2020. Retrieved 5 June 2019.

- Bushe, Andrew (4 August 2002). "Ardnacrusha – Dam hard job". Sunday Mirror. Archived from the original on 21 February 2008. Retrieved 18 September 2010.

- Arendt, Hannah (1964). Eichmann in Jerusalem. Ein Bericht von der Banalität des Bösen. München. p. 163. ISBN 978-3-492-24822-8.

- Guilpin, Anaïs. "Le travail forcé dans les camps". L'Histoire par l'image (in French). Retrieved 24 January 2015.

- Forced labor at Siemens Ravensbrück

- German Industry and the Third Reich: Fifty Years of Forgetting and Remembering Archived 30 October 2012 at the Wayback Machine. Adl.org. Retrieved on 19 September 2013.

- Anna Vavak: Siemens & Halske AG in the women's concentration camp at Ravensbrück

- RLS – Siemens & Halske im Frauenkonzentrationslager Ravensbrück Archived 22 April 2016 at the Wayback Machine. Rosalux.de. Retrieved on 19 September 2013.

- Bärbel Schindler-Saefkow – Jg. 1943, Dr. phil., Historikerin, Leiterin des Projekts »Gedenkbuch Ravensbrück".

- Margarete Buber: 303f As prisoners of Stalin and Hitler, Frankf / Main, Berlin 1993

- "Setting the Course for the Future – The Founding of Siemens AG". Siemens Historical Institute. Archived from the original on 25 October 2020. Retrieved 5 June 2019.

- Vanessa Fuhrmans (15 April 2011). "Siemens Rethinks Nuclear Ambitions". The Wall Street Journal.

- "Funding Universe - History of Marconi plc". fundinguniverse.com. Retrieved 14 July 2012.

- Malerba, Franco. The Semiconductor Business: The Economics of Rapid Growth and Decline. University of Wisconsin Press, 1985. p. 166.

- Rodengen, pp. 59–60.

- Reindustrialization Or New Industrialization: Minutes of a Symposium, January 13, 1981, Part 3. National Academies, 1981. p. 53.

- Rodengen, p. 60.

- ADVANCED MICRO COMPUTERS, INC. Archived 4 November 2014 at the Wayback Machine. CaliforniaFirm.us.

- ADVANCED MICRO COMPUTERS, INC. Archived 4 November 2014 at the Wayback Machine. CaliforniaCompaniesList.com.

- Freiberger, Paul. "AMD sued for alleged misuse of subsidiary's secrets". InfoWorld. 20 June 1983. p. 28.

- Mini-micro Systems, Volume 15. Cahners Publishing Company, 1982. p. 286.

- Rodengen, p. 62.

- "Siemens and Advanced Micro Devices Agree to Split Joint Venture". The Wall Street Journal. 14 February 1979. p. 38.

- Swaine, Michael. "Eight Companies to produce the 8086 chip". InfoWorld. 30 November 1981. p. 78.

- Rodengen, p. 73.

- "Allis-Chalmers & Siemens-Allis Electrical Control Parts". information about Siemens-Allis. Accontroldirect.com. Archived from the original on 26 November 2010. Retrieved 19 August 2010.

- Wald, Matthew L. (3 August 1989). "ARCO to Sell Siemens Its Solar Energy Unit". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 26 April 2019.

- "History: The Best of Both Worlds". Wincor Nixdorf. Archived from the original on 2 June 2007. Retrieved 10 October 2018.

- Gálvez-Muñoz, Lina; Jones, Geoffrey G (26 July 2005). Foreign Multinationals in the United States. Routledge. p. 104. ISBN 9781134532100. Retrieved 10 October 2018.

- Markoff, John (14 December 1988). "I.B.M. to Sell Rolm to Siemens". The New York Times. Retrieved 10 October 2018.

- "Siemens Plessey Electronic Systems". 1988. Archived from the original on 6 June 2013.

- Reuters (15 November 1997). "Siemens to Buy Power Unit From Westinghouse". LA Times. Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 2 April 2013.

- Siemens' Electromechanical Components Group to be sold to Tyco, DGAP, 28 September 1999, archived from the original on 20 October 2020, retrieved 19 February 2020

- Dave Mote. "Company History: Shared Medical Systems Corporation". Answers.com.

- "Company News: Siemans to acquire Shared Medical Systems". The New York Times. 2 May 2000.

- "Mannesmann Archive – brief history". Mannesmann-archiv.de. 2000. Archived from the original on 23 January 2015.

- "Report to Securities and Exchange Commission, Washington, D.C." (PDF). Siemens.com. 27 August 2002.

- Bruce Davis (1 June 2000). "Article: Bosch, Siemens to buy Atecs Mannesmann unit. (Brief Article)". European Rubber Journal Article. Highbeam.com. Archived from the original on 19 January 2012.

- "Company Overview of Moore Products Co". Bloomberg News. Retrieved 14 February 2018.

- "Chemtech: A Siemens' company". Chemtech.com. Archived from the original on 1 February 2008.

- "Chemtech – A Siemens Company". energy.siemens.com. Archived from the original on 9 April 2014.

- "Siemens completes sale of business activities to private equity house KKR". 26 September 2002. Archived from the original on 21 October 2020. Retrieved 27 July 2013.

- "Shell Renewables Completes Acquisition of Siemens Solar". www.renewableenergyworld.com. 29 April 2002. Archived from the original on 28 October 2020. Retrieved 26 April 2019.

- "Acquisition of Flow Division of Danfoss successful". Automation.siemens.com. 6 September 2003. Archived from the original on 28 July 2011.

- "Siemens to buy IndX Software". ITworld.com. 2 December 2003. Retrieved 18 September 2010.

- "Siemens Venture Capital – Investments". IndX Software Corporation. Finance.siemens.com.

- United Nations Security Council 4943. S/PV/4943 page 7. 15 April 2004. Retrieved 6 September 2007.

- Malcolm Moore (7 April 2003). "Siemens to buy Alstom turbines". London: Telegraph.co.uk. Archived from the original on 11 January 2022. Retrieved 18 September 2010.

- "Alstom completes the sale of its medium gas turbines and industrial steam turbines businesses to Siemens". Alstom.com. 1 August 2003.

- "Siemens covets style over substance". 11 February 2003.

- "SIEMENS UNIT OPENS OFFICE IN SAN JOSE". Archived from the original on 1 November 2013.

- "SIEMENS TARGETS 10pc OF HANDSETS". 7 March 2003.

- "Siemens puts fashion way out in front". Archived from the original on 30 October 2013.

- Eva Balslev (20 October 2004). "Siemens buys Bonus Energy". Guidedtour.windpower.org. Archived from the original on 21 March 2011.

- "Siemens to acquire Bonus Energy A/S in Denmark and enter wind energy business". Edubourse.com. 20 October 2004. Archived from the original on 10 July 2011. Retrieved 18 September 2010.

- "Siemens Venture magazine" (PDF). energy.siemens.com. May 2005. p. 5. Archived from the original (PDF) on 26 February 2011. Retrieved 19 August 2010.

- Michael Newlands (17 June 2004). "Siemens ICN to invest E100m in Korean unit Dasan". Total Telecom. Totaltele.com. Archived from the original on 28 September 2011. Retrieved 19 August 2010.

- "Nokia Siemens Networks sells 56 pc stake in Dasan". Economictimes.indiatimes.com. Reuters. 28 August 2008.

- "Siemens hits the UK market running with Photo-Scan takeover". CCTV Today. 1 November 2004.

- "Siemens acquires US Filter Corp (Siemens setzt auf Wasser und plant weitere Zukaufe)". Europe Intelligence Wire. Accessmylibrary.com. 13 May 2004. Retrieved 18 September 2010.

- "Chrysler Group's Huntsville electronics ops to be acquired by Siemens VDO Automotive". Emsnow.com. 10 February 2004. Archived from the original on 2 January 2013.

- John Cox (10 December 2004). "Siemens swallows start-up Chantry". Network World Fusion Network World US. News.techworld.com. Archived from the original on 18 July 2011. Retrieved 18 September 2010.

- "Company History: Flender". Flender.com. Archived from the original on 10 March 2012.

- "Bewator: a bright future with a brand new name" (PDF). buildingtechnologies.siemens.com. April 2008. Archived from the original (PDF) on 7 October 2011.

- "Siemens Power Generation Acquires Pittsburgh-Based Wheelabrator Air Pollution Control, Inc.; Business Portfolio Expanded to Include Emission Prevention and Control Solutions". Business Wire. Findarticles.com. 5 October 2005. Archived from the original on 16 October 2015.

- "Siemens uebernimmt AN Windenergie GmbH". Windmesse.de. 3 November 2005.

- Higgins, Dan (11 January 2005). "German conglomerate Siemens buys Schenectady, N.Y.-based energy software firm". Times Union (Albany, New York). Accesssmylibrary.com.

- "Siemens buys CTI molecular imaging". Instrument Business Outlook. Allbusiness.com. 15 May 2005.

- "Siemens acquires CTI Molecular Imaging". Thefreelibrary.com.

- "Siemens Power Transmission acquires Shaw Power Tech Int Ltd from Shaw Group Inc". Thomson Financial Mergers & Acquisitions. Alacrastore.com. December 2004.

- "Siemens Power Transmission & Distribution has acquired the business activities of Shaw Power Technologies Inc. in the U.S. and Shaw Power Technologies Limited in the U.K." Utility Automation & Engineering T&D. Alacrastore.com. 1 January 2005.

- "Siemens acquires Transmitton" (PDF). Press release. Siemenstransportation.co.uk. 15 August 2005. Archived from the original (PDF) on 8 November 2007.

- "Bloomberg.com". 20 May 2007. Retrieved 12 January 2008.

- "Report: Siemens Scandal May Involve Top Executives". DW. 27 November 2006.

- Schubert, Siri; Miller, T. Christian (20 December 2008). "At Siemens, Bribery Was Just a Line Item". The New York Times.

- O'Reilly, Cary; Matussek, Karin (16 December 2008). "Siemens to Pay $1.6 Billion to Settle Bribery Cases". The Washington Post.

- Gow, David (15 December 2008). "Record US fine ends Siemens bribery scandal". The Guardian.

- "Nigeria probes Siemens bribe case".

- "United States of America v. Siemens Aktiengesellschaft" (PDF). United States District Court for the District of Columbia. 2 May 2013.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain. - Sims, Richard (2001). Japanese Political History Since the Meiji Renovation 1868–2000. Palgrave Macmillan. p. 113. ISBN 0-312-23915-7.

- Sims, G. Thomas (15 May 2007). "The New York Times". Retrieved 15 May 2007.

- Oduor, Jacinta Anyango; Fernando, Francisca M. U.; Flah, Agustin; Gottwald, Dorothee; Hauch, Jeanne M.; Mathias, Marianne; Park, Ji Won; Stolpe, Oliver (2013). Left Out of the Bargain: Settlements in Foreign Bribery Cases and Implications for Asset Recovery. World Bank Publications. pp. 80, 133. ISBN 9781464800870.

- "Press release: Siemens Launches US$100 Million Initiative for Anti-Corruption". World Bank and Siemens. 9 December 2009.

- "Press release: Siemens selects initial projects for US$100 million Integrity Initiative". World Bank and Siemens. 9 December 2010.

- "Press release: Siemens Integrity Initiative enters the second round" (PDF). World Bank and Siemens. 10 December 2014. Archived from the original (PDF) on 7 August 2020. Retrieved 29 July 2017.

- "Nigeria: Bribe Scandal – Siemens Fined N7 Billion".

- "Debt crisis: Greek government signs €330m settlement with Siemens". Telegraph.co.uk. 27 August 2012. Archived from the original on 11 January 2022. Retrieved 16 February 2016.

- "Υπόθεση Siemens: Στις 24 Φεβρουαρίου αρχίζει η δίκη". 22 November 2016.

- "Courts issue warrants for arrest of Karavelas and Christoforakos". 5 February 2014.

- "Και τρίτο ευρωπαϊκό ένταλμα σύλληψης".

- "Ex-Boss Could Help Shed Light on Corruption". Der Spiegel. 29 June 2009.

- "Ελεύθερος ο Χριστοφοράκος".

- "Ex-power company execs charged in massive Siemens bribery case". The Times of Israel. Retrieved 26 August 2016.

- NBC. "Bayer Sells Diagnostics unit to Siemens" Archived 12 August 2016 at the Wayback Machine, NBC News, 29 June 2006. Retrieved 12 May 2016.

- "Siemens Acquires Controlotron". Impeller.net. Archived from the original on 27 November 2010. Retrieved 19 August 2010.

- "Controlotron Company Reference". Sea.siemens.com. []

- Archived 4 April 2012 at the Wayback Machine

- "EU cracks down on electricity-gear cartel". EurActiv. 25 January 2007. Archived from the original on 3 March 2016. Retrieved 7 February 2008.

- "Board member arrested in new blow for Siemens".

- Associated Press quoted by Forbes: Nokia-Siemens Venture to Start in April, 15 March 2007

- International Herald Tribune: Bribery trial deepens Siemens woes Archived 11 December 2008 at the Wayback Machine, 13 March 2007

- Agande, Ben; Miebi Senge (5 December 2007). "Bribe: FG blacklists Siemens". Vanguard. Vanguard Media. Retrieved 7 December 2007.

- Taiwo, Juliana (6 December 2007). "FG Blacklists Siemens, Cancels Contract". Thisday. Leaders & Company. Archived from the original on 8 December 2007. Retrieved 7 December 2007.

- Merrill, Molly. "Siemens acquires Dade Behring for $7B" Archived 5 June 2016 at the Wayback Machine, Healthcare IT News, 25 July 2007. Retrieved 12 May 2016.

- "Siemens to spin off SEN into JV with Gores Group". Reuters. 29 July 2008.

- "Siemens invests $ 15 million in Israeli solar company Arava Power" (PDF) (Press release). Siemens AG. 28 August 2009. Retrieved 27 June 2011.

- Cellan-Jones, Rory (22 June 2009). "Hi-tech helps Iranian monitoring". BBC News. Retrieved 7 April 2010.

- Eli Lake (13 April 2009). "Fed contractor, cell phone maker sold spy system to Iran". Washington Times.

- Rhoads, Christopher; Chao, Loretta (22 June 2009). "Iran's Web Spying Aided By Western Technology". The Wall Street Journal.

- Valentina Pop (3 June 2010), "Nokia-Siemens Rues Iran Crackdown Role", www.businessweek.com, archived from the original on 5 March 2016

- Tarmo Virki (13 December 2011), "Nokia Siemens to ramp down Iran operations", ca.reuters.com

- Matt Warman (11 February 2010), "Nokia Siemens "instrumental to persecution and arrests of Iranian dissidents", says EU", www.telegraph.co.uk, London, archived from the original on 11 January 2022

- "Siemens to decisively strengthen its position in the growth market solar thermal power.Reference number: Siemens ERE200910.13e" (PDF) (Press release). Siemens AG. Press Office Energy Sector – Renewable Energy Division. 15 October 2009. Archived from the original (PDF) on 4 November 2012. Retrieved 4 May 2011.

- "Siemens to quit nuclear industry". BBC News. 18 September 2011.

- "Siemens To Acquire LMS International – Quick Facts". 8 November 2012. Retrieved 31 July 2013.

- Ewing, Adam (1 July 2013). "Nokia Buys Out Siemens in Equipment Venture for $2.2 Billion (4)". Businessweek. Retrieved 5 August 2013.

- Maria Sheahan (6 August 2013). "Siemens wins $967 million order from Saudi Aramco". Reuters. Archived from the original on 18 July 2020. Retrieved 2 July 2017.

- Stanley Reedmarch (25 March 2014). "Siemens to Invest $264 Million in British Wind Turbine Project". The New York Times.

- "Rolls-Royce sells energy arm to Siemens in £1bn deal". The Telegraph. London. 7 May 2014. Archived from the original on 11 January 2022.

- Jens Hack and Natalie Huet, "Siemens and Mitsubishi challenge GE with Alstom offer", Reuters (16 June 2014). Archived 16 October 2015 at the Wayback Machine

- Pulsinelli, Olivia (22 December 2015). "Dresser-Rand to close Houston facility, cut jobs". Houston Business Journal. Retrieved 6 December 2017.

- Ludwig Burger (22 September 2014). "Siemens in agreed $7.6 billion deal to buy Dresser-Rand". Reuters.

- "Siemens to expand its digital industrial leadership with acquisition of Mentor Graphics". www.siemens.com. Retrieved 14 November 2016.

- Department of Justice, Office of Public Affairs (27 November 2017). "U.S. Charges Three Chinese Hackers Who Work at Internet Security Firm for Hacking Three Corporations for Commercial Advantage". United States Department of Justice.

- "Siemens buys Fast Track Diagnostics to boost molecular offering". Reuters. 15 December 2017. Retrieved 15 December 2017.

- "Siemens strengthens its digital enterprise leadership with acquisition of mendix". www.siemens.com.

- Allen, Nathan. "Siemens to acquire J2 Innovations". MarketWatch. Retrieved 28 April 2020.

- Wilson, Alexandra. "Siemens Doubles Down On Smart Building Investment, Acquiring Oakland Startup Comfy". Forbes. Retrieved 28 April 2020.

- "Siemens drives digital transformation in buildings with acquisition of Enlighted". Retrieved 28 April 2020.

- "Siemens, Orascom sign deal to rebuild Iraq power plant". Reuters. 14 September 2019. Retrieved 17 September 2019.

- Massola, James. "Big surge in opposition to Adani, new polling reveals". The Sydney Morning Herald. Retrieved 12 February 2020.

- Readfearn, Graham. "Adani coalmine: Siemens CEO has 'empathy' for environment but refuses to quit contract". The Guardian. Retrieved 12 February 2020.

- Prasad, Rachita. "Siemens to acquire C&S Electric for Rs 2,100 crore". The Economic Times. Retrieved 27 February 2021.

- "CCI approves Siemens' acquisition of C&S Electric". @businessline. 20 August 2020. Retrieved 27 February 2021.

- "Siemens acquires iMetrex Technologies". Hindustan Times. 24 April 2007. Retrieved 27 February 2021.

- "Siemens baut fokussierten Energieriesen und steigert Leistungsfäh ..." press.siemens.com (in German). Retrieved 2 September 2020.

- magazin, manager. "Joe Kaeser will keine Kohle mehr - manager magazin - Unternehmen". www.manager-magazin.de (in German). Retrieved 2 September 2020.

- "Siemens Healthineers AG (SEMHF) announced on Sunday that it plans to acquire U.S. cancer device and software company Varian Medical Systems (VAR) in an all-stock deal valued at $16.4 billion". 2 August 2020. Retrieved 3 August 2020.

- "Siemens Acquires Wattsense to Boost IoT Systems for Small and Medium Buildings". Automation.com. 6 October 2021.

- Innovates, Dallas; Cummings, Kevin (15 July 2022). "Follow the Money: Fort Worth Biotech Raises $16M, VC Firm Raises $25M for Debut Fund, S2 Capital Surpasses Blackstone as Region's Most Active Multifamily Investor, and More". Dallas Innovates. Retrieved 20 July 2022.

- "Profile: Siemens AG". Reuters. Retrieved 3 September 2012.

- Siemens. "About Siemens". www.siemens.com. Retrieved 8 October 2018.

- Henning, Eyk; Alessi, Christopher (22 October 2014). "Siemens In Talks To Sell Hearing-Aid Business". European Business News. The Wall Street Journal.

- Sivantos."Siemens Audiology business is now Sivantos" Archived 3 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine, Sivantos Website, 16 January 2015. Retrieved 12 May 2016.

- "Annual Report 2011" (PDF). Siemens. Retrieved 3 September 2012.

- "Siemens Traction Equipment Ltd., Zhuzhou" (PDF). CN.siemens.com. Archived from the original (PDF) on 21 September 2013.

- "Company Overview of Omnetric Group". Bloomberg. Retrieved 1 August 2017.

- Bingemann, Mitchell (22 August 2013). "Silcar's top staff go as Thiess puts in its own". The Australian. Retrieved 13 February 2014.

- Adhikari, Supratim (22 August 2013). "Silcar old guard makes way as Thiess exerts control". Business Spectator. Archived from the original on 8 March 2014. Retrieved 13 February 2014.

- "Capabilities – Services – Telecommunications". Thiess. Archived from the original on 22 February 2014. Retrieved 13 February 2014.

- "Siemens Bilanz, Gewinn und Umsatz | Siemens Geschäftsbericht | 723610". wallstreet-online.de. Retrieved 4 November 2018.

- "SIEGY Key Statistics | SIEMENS AG Stock - Yahoo Finance". finance.yahoo.com. Retrieved 4 November 2018.

- Annual Report Archived 8 April 2016 at the Wayback Machine as of July 2015

- "Chairmen of the Managing Board and Supervisory Board of Siemens & Halske AG and Siemens-Schuckertwerke GmbH / AG or Siemens AG" (PDF). Siemens. Archived from the original (PDF) on 29 October 2020. Retrieved 28 August 2012.

- "Managing Board". Siemens. Retrieved 5 March 2021.

- "Managing Board" Archived 9 September 2016 at the Wayback MachineSiemens Global Website, Retrieved 17 October 2016.

Further reading

- Shaping the Future. The Siemens Entrepreneurs 1847–2018. Ed. Siemens Historical Institute, Hamburg 2018, ISBN 9-783867-746243.

- Weiher, Siegfried von /Herbert Goetzeler (1984). The Siemens Company, Its Historical Role in the Progress of Electrical Engineering 1847–1980, 2nd ed. Berlin and Munich.

- Feldenkirchen, Wilfried (2000). Siemens, From Workshop to Global Player, Munich.

- Feldenkirchen, Wilfried / Eberhard Posner (2005): The Siemens Entrepreneurs, Continuity and Change, 1847–2005, Ten Portraits, Munich.

- Greider, William (1997). One World, Ready or Not. Penguin Press. ISBN 0-7139-9211-5.

- Margarete Buber: 303f As prisoners of Stalin and Hitler, Frankf / Main, Berlin 1993

- See Carola Sachse: Jewish forced labor and non-Jewish women and men at Siemens from 1940 to 1945, in: International Scientific Correspondence, No. 1/1991, pp. 12–24; Karl-Heinz Roth: forced labor in the Siemens Group (1938 -1945). Facts, controversies, problems, in: Hermann Kaienburg (ed.): concentration camps and the German Economy 1939–1945 (Social studies, H. 34), Opladen 1996, pp. 149–168; Wilfried Feldenkirchen: 1918–1945 Siemens, Munich 1995, Ulrike fire, Claus Füllberg-Stolberg, Sylvia Kempe: work at Ravensbrück concentration camp, in: Women in concentration camps. Bergen-Belsen. Ravensbrück, Bremen, 1994, pp. 55–69; Ursula Krause-Schmitt: The path to the Siemens stock led past the crematorium, in: Information. German Resistance Study Group, Frankfurt / Main, 18 Jg, No. 37/38, Nov. 1993, pp. 38–46; Sigrid Jacobeit: working at Siemens in Ravensbrück, in: Dietrich Eichholz (eds) War and economy. Studies on German economic history 1939–1945, Berlin 1999.

- Bundesarchiv Berlin, NS 19, No. 968, Communication on the creation of the barracks for the Siemens & Halske, the planned production and the planned expansion for 2,500 prisoners "after direct discussions with this company": Economic and Administrative Main Office of the SS ( WVHA), Oswald Pohl, secretly, to Reichsführer SS (RFSS), Heinrich Himmler, dated 20 October 1942.

- Karl-Heinz Roth: forced labor in the Siemens Group, with a summary table, page 157 See also Ursula Krause-Schmitt: "The road to Siemens stock led to the crematorium past over," pp. 36f, where, according to the catalogs of the International Tracing Service Arolsen and Martin Weinmann (eds.).. The Nazi camp system, Frankfurt / Main 1990 and Feldkirchen: Siemens 1918–1945, pp. 198–214, and in particular the associated annotations 91–187.

- MSS in the estate include Wanda Kiedrzy'nska, in: National Library of Poland, Warsaw, Manuscript Division, Sygn. akc 12013/1 and archive the memorial I/6-7-139 RA: see also: Woman Ravensbruck concentration camp. An overall presentation, State Justice Administration in Ludwigsburg, IV ART 409-Z 39/59, April 1972, pp. 129ff.

External links

- Official website

- Documents and clippings about Siemens in the 20th Century Press Archives of the ZBW

- Siemens Historical Institute