40 Wall Street

40 Wall Street, also known as the Trump Building, is a 927-foot-tall (283 m) neo-Gothic skyscraper on Wall Street between Nassau and William streets in the Financial District of Manhattan in New York City. Erected in 1929–1930 as the headquarters of the Manhattan Company, the building was originally known as the Bank of Manhattan Trust Building, and also as the Manhattan Company Building, until its founding tenant merged to form the Chase Manhattan Bank. It was designed by H. Craig Severance with Yasuo Matsui and Shreve & Lamb.

| 40 Wall Street | |

|---|---|

40 Wall Street in December 2005 | |

| |

| Alternative names | The Trump Building, Manhattan Company Building |

| Record height | |

| Tallest in the world from April 1930 to May 27, 1930[I] | |

| Preceded by | Woolworth Building |

| Surpassed by | Chrysler Building |

| General information | |

| Architectural style | Neo-Gothic |

| Location | 40 Wall Street New York, NY 10005 |

| Coordinates | 40°42′25″N 74°00′35″W |

| Construction started | May 1929 |

| Completed | May 1, 1930[1] |

| Opening | May 26, 1930 |

| Landlord | Donald Trump |

| Height | |

| Architectural | 927 ft (283 m) |

| Top floor | 836 ft (255 m) |

| Technical details | |

| Floor count | 70 (+2 below ground) |

| Floor area | 1,111,675 sq ft (103,278.0 m2) |

| Lifts/elevators | 36 |

| Design and construction | |

| Architect(s) | H. Craig Severance (main architect) Yasuo Matsui (associate architect) Shreve & Lamb (consulting architect) |

Manhattan Company Building | |

U.S. Historic district Contributing property | |

NYC Landmark No. 1936

| |

| Location | 40 Wall Street, New York, NY |

| Area | less than one acre |

| Built | 1929–1930 |

| Architect | H. Craig Severance, Yasuo Matsui, et al. |

| Architectural style | Skyscraper |

| Part of | Wall Street Historic District (ID07000063) |

| NRHP reference No. | 00000577[2] |

| NYCL No. | 1936 |

| Significant dates | |

| Added to NRHP | June 16, 2000 |

| Designated NYCL | December 12, 1995 |

| References | |

| [3][4] | |

The building is on an L-shaped site. While the lower section has a facade of limestone, the upper stories incorporate a buff-brick facade and contain numerous setbacks. Other features of the facade include spandrels between the windows on each story, which are recessed behind the vertical piers on the facade. At the top of the building is a pyramid with a spire at its pinnacle. The Manhattan Company's main banking room and board room were on the lower floors, while the remaining stories were rented to tenants. The former banking room was converted into a Duane Reade store.

Plans for 40 Wall Street were revealed in April 1929, with the Manhattan Company as the primary tenant, and the structure was completed in May 1930. 40 Wall Street and the Chrysler Building were competing for the distinction of world's tallest building at the time of both buildings' construction, though the Chrysler Building ultimately won that title. In its early years, 40 Wall Street suffered from low tenancy rates, as well as a plane crash in 1946. Ownership of the building and the land underneath it, as well as the leasehold on the building, has changed several times throughout its history. Since 1982, the building has been owned by two German companies. The leasehold was once held by interests on behalf of former Philippine president Ferdinand Marcos, though in 1995, a company controlled by developer and later U.S. president Donald Trump assumed the lease.

The building was designated a city landmark by the New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission in 1995 and was added to the National Register of Historic Places (NRHP) in 2000. It is also a contributing property to the Wall Street Historic District, a NRHP district created in 2007.

Site

40 Wall Street is in the Financial District of Manhattan, in the middle of the block bounded by Pine Street to the north, William Street to the east, Wall Street to the south, and Nassau Street to the west. The site is L-shaped, with a longer facade on Pine Street than on Wall Street.[5][6][7] The lot covers 33,600 square feet (3,120 m2) and measures 209 feet (64 m) on Pine Street and 150 feet (46 m) on Wall Street.[8] The lot has a total area of 34,360 square feet (3,192 m2).[7]

40 Wall Street is surrounded by numerous buildings, including Federal Hall National Memorial and 30 Wall Street to the west; 44 Wall Street and 48 Wall Street to the east; 28 Liberty Street to the north; and 23 Wall Street and 15 Broad Street to the south. The site slopes down southward, so that the Pine Street entrance is on the second floor while the Wall Street entrance is on the first floor.[6]

Architecture

The building was designed by lead architect H. Craig Severance, associate architect Yasuo Matsui, and consulting architects Shreve & Lamb.[9][8][10] Moran & Proctor were consulting engineers for the foundation,[8][11] the Starrett Corporation was the builder,[12] and Purdy and Henderson were the structural engineers.[9] The interior was designed by Morrell Smith with Walker & Gillette.[13] While 40 Wall Street's facade has "modernized French Gothic" features, its massing is designed more similarly to the Art Deco style, and there are also elements of classical architecture as well as abstract shapes.[13][14][15]

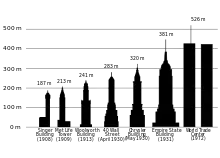

40 Wall Street is 70 stories tall, with two additional basement stories.[3][4][lower-alpha 1] The building's pinnacle reaches 927 feet (283 m), briefly making it the world's tallest building upon its completion.[17][18] The Bank of Manhattan Building had an observation deck on the 69th and 70th floors, 836 feet (255 m) above the street, with the observatory able to fit up to 100 people.[19] The observatory was closed to the public sometime after World War II.[9]

Form

40 Wall Street, like many other early-20th-century skyscrapers in New York City, is designed as if it were a standalone tower. It is one of several skyscrapers in the city that have pyramidal roofs.[14][lower-alpha 2] The floors at the six-story base cover the entire "L"-shaped lot, while the seventh through 35th stories (making up the middle section) are shaped in a "U", with two wings of different lengths facing west.[20][21] The massing of the building on the seventh through 35th stories occupies nearly the entire lot.[6][21] Above the 35th story, the building rises as a smaller, square tower through the 62nd story.[21][22]

40 Wall Street incorporates several setbacks to conform with the 1916 Zoning Resolution.[14] On the Wall Street side, the central portion of the facade is recessed through the 26th floor, while symmetrical pavilions project slightly on either side, with setbacks above the 17th, 19th, and 21st floors. The entire Wall Street facade has setbacks above the 26th, 33rd and 35th floors. The Pine Street facade is asymmetrical, with the western pavilion being much longer; it has a setback above the 12th floor. This side also contains setbacks above the 17th, 19th, 23rd, 26th, 28th, and 29th floors. The pairs of projecting pavilions on both sides are connected at the eighth floor by a dormer.[23]

The building's west-facing wings are of different lengths; the northern wing is significantly longer and has cooling systems atop it, but both wings have minor setbacks above the 26th and 33rd floors, and rise only to the 35th floor. The eastern facade does not have any setbacks below the 35th story.[23]

Facade

In general, the facade is composed of buff-colored brick, as well as decorative elements made of terracotta and brick. The vertical bays, which contain the building's windows, are separated by piers.[20][21] The piers are flat, a characteristic of the Art Deco style.[15] Spandrel panels, which separate the rows of windows on each floor, are generally recessed behind the piers; the spandrels are generally darker on upper stories.[20][21] The building's window openings, initially composed of one-over-one sash windows, were later replaced by numerous types of window-pane arrangements or by louvers.[21]

Base

The first through sixth stories contain a limestone-and-granite facade. 40 Wall Street contains a granite facade on the first story, which faces Wall Street. The second-to fifth-floor facades on both sides consist of a colonnade with pilasters made of limestone.[6][14]

On the Wall Street side, the first floor initially had a central entryway with three bronze-and-glass doors, flanked by numerous entrances to the elevator lobby and the lower banking room.[21] Double-height bronze-and-glass windows spanned the second and third floors, while cast-iron windows were on the fourth through sixth floors.[23] Above the central entrance was a doorway that was topped by Elie Nadelman's Oceanus sculpture (also called Aquarius);[24][21] it had been removed by the late 20th century.[25][26] Between 1961 and 1963, Carson, Lundin & Shaw, added the granite cladding and reconfigured the doorways on the first floor, as well as replaced the second- through sixth-floor windows.[27] By 1995, the entrance had been configured with seven bronze rectangular doors and three revolving doors, recessed behind the main facade. Letters reading "The Trump Building" are above the first floor, while the fourth floor has a pair of flagpoles.[23]

The Pine Street side was arranged similarly to the Wall Street side and was similarly redesigned in 1961–1963. A 6-foot-diameter (1.8 m) clock existed on the Pine Street facade from 1967 to 1993. This portion of the facade consists of 11 bays; at ground level, this includes an entrance to the main elevator lobby, a service entrance, and storefronts slightly above grade. As with the Wall Street side, the fourth floor contains a pair of flagpoles.[23]

Upper stories

The eighth through 35th stories comprise the midsection of the building. There are eight flagpoles on the ninth floor of the Wall Street side, four on each pavilion. On the 19th floor of the Pine Street side, there are louvers in place of window openings.[23] On the 36th through 62nd stories, there are brick spandrels between the windows on each story.[20][23] The spandrels above the 52nd through 57th floors are made of terracotta; above the 58th through 60th floors, terracotta with buttresses; and above the 61st and 62nd floors, darker bricks with pediments and rhombus patterns.[20]

The building contains a pyramidal roof originally made of lead-coated copper.[11][20][28] There is a cornice surrounding the roof.[20] On top is a spire that contains a flagpole as well as a crystal ball.[23] The roof contains French Renaissance-style detail, a design element intended to make the building appear much older than it actually was.[28]

Features

The building's frame is made of steel.[6] The superstructure contains eight main columns, each of which weighs 22 short tons (20 long tons; 20 t) and can carry loads of up to 4.6 million pounds (2,100,000 kg).[29]

Interior space

As originally arranged, 40 Wall Street hosted the Manhattan Company's banking facilities on the first through sixth floors; offices on its middle floors; and machinery, an observation deck, and recreation areas on the top floors. There were also 43 elevators inside the building when it opened;[14] as of 2020, there are 36 elevators.[3] The Wall Street lobby contains escalators to the second floor,[20] as well as stairs to the two basement levels, which contained the Manhattan Company's vault.[30] The modern design of the lobby dates to a 1999 renovation by Der Scutt.[4][28] Following Scutt's renovation, the lobby contains many bronze and marble surfaces.[28]

On the second floor was the main banking room, which measured 150 by 185 feet (46 by 56 m).[31] The banking room could be accessed directly from Pine Street, where there was a foyer with two pairs of octagonal black-marble Ionic columns. The room itself consisted of a main hall below five groin vaults; there are arcades on either side of the main hall, which lead to smaller vaulted spaces. Murals by Ezra Winter once lined the walls, but have been removed.[20] As of 2011, the second floor is occupied by a Duane Reade convenience store.[32] On the south side, a pair of stairs on the south wall flanks the escalators and leads up to what was originally the officers' quarters, a rectangular room with five white-marble columns.[20] This space had three doorways that led to private offices of Manhattan Company executives; the doorways to these offices contained round carvings with symbols of various economic sectors.[30]

On the fourth floor was the board room of the Manhattan Company, designed in the Georgian style as an imitation of Independence Hall's Signers' Room. The board room contains several elements of the Doric order, such as columns, pilasters, and a frieze. Wooden doors and fireplaces with segmental arches are on the eastern wall, while false windows are on the western wall.[30]

History

The Manhattan Company was established by Aaron Burr in 1799, ostensibly to provide clean water to Lower Manhattan. The company's true focus was banking, and it served as a competitor to Alexander Hamilton's Bank of New York, which previously held a monopoly over banking in New York City.[33][34][35] The Manhattan Company was headquartered at a row house at 40 Wall Street,[31] which served as the company's "office of discount and deposit".[33] By the early 20th century, the company was growing quickly, having acquired numerous other banks.[33][34][36]

Development

The idea for the current skyscraper was devised by banker George L. Ohrstrom.[37][38][39] Ohrstrom began land acquisition for the building in 1928,[33] originally going under the name 36 Wall Street Corporation.[40] Stakeholders in the corporation included Ohrstrom and the builders Starrett Brothers (later Starrett Corporation).[41][42] In September of that year, the 36 Wall Street Corporation acquired 34–36 Wall Street under a 93-year lease to the Iselin estate. At the time, the syndicate hoped to build a 20-story building.[43][44] By that December, Ohrstrom had purchased four buildings, with frontage along 27–33 Pine Street and 34–38 Wall Street, and controlled a total area of 17,000 square feet (1,600 m2).[45][46] The plans had been updated and the syndicate was now envisioning a 45-story building.[46]

Planning

In January 1929, the 36 Wall Street Corporation planned a bond issue to fund the building's construction.[47] That March, Ohrstrom announced that H. Craig Severance would design a 47-story structure at 36 Wall Street.[33][8][48] The syndicate bought 25 Pine Street the same month.[49] Shortly after Severance's original plans were announced, the skyscraper was modified to have 60 floors, but it was still shorter than the 792-foot (241 m) Woolworth Building and the then-under-construction, 808-foot (246 m) Chrysler Building.[50] By April 8, 1929, The New York Times reported that Ohrstrom and Severance were planning to revise the skyscraper's plans to make it the world's tallest building.[51] Two days later, it was announced that Severance had increased the tower's height to 840 feet (260 m) with 62 floors, exceeding the heights of the Woolworth and Chrysler buildings.[52][53] It was also announced that the Manhattan Company would be 36 Wall Street's main tenant and that the new building would be known as the Bank of Manhattan Building or the Manhattan Company Building.[53] The height of the building was made possible by the 33,600-square-foot (3,120 m2) lot, which was one of the densely-developed Financial District's largest lots.[8]

The builders intended to spend large sums to reduce the construction period to one year, allowing rental tenants to move into the building sooner.[33] By mid-April 1929, the tenants of existing buildings had moved elsewhere.[54] The Manhattan Company and Chrysler buildings started competing for the distinction of "world's tallest building".[4][55] The "Race into the Sky", as popular media called it at the time, was representative of the country's optimism in the 1920s, fueled by the building boom in major cities.[56] The Manhattan Company Building was revised to 927 feet (283 m) later in April 1929, which would make it the world's tallest.[57] Severance then publicly claimed the title of the world's tallest building,[4][lower-alpha 3] but the Starrett Corporation denied all allegations that the plans had been changed.[58]

Construction

Construction of the Manhattan Company Building began in May 1929.[59] By that time, the syndicate developing the building was known as the 40 Wall Street Corporation, and the building was also known as 40 Wall Street. The same month, the Manhattan Company leased its lots at 40–42 Wall Street and 35–39 Pine Street to the 40 Wall Street Corporation for 93 years. Ownership would be divided among the Manhattan Company, Iselin estate, and the 40 Wall Street Corporation, with the Manhattan Company holding a plurality stake.[60] Simultaneously, the U.S. government invited bids on the adjoining building at 28–30 Wall Street, then occupied by a federal assay office.[33] In June 1929, the government announced that the 40 Wall Street Corporation had placed the highest bid for the lot, bringing the syndicate's total land holding to 40,000 square feet (3,700 m2).[61][62][63] However, the assay office plot was not to be part of the new skyscraper, instead being reserved for the Manhattan Company's future expansion.[63][64] While construction was ongoing, the Manhattan Company moved to temporary headquarters.[31]

Excavations for 40 Wall Street were complicated by numerous factors. There was little available space to store materials; the surrounding lots were all densely built up; the bedrock was 64 feet (20 m) below street level, beneath boulders and quicksand; and the previous buildings on the lot had contained foundations of up to 5 feet (1.5 m) thick. Therefore, the foundation of 40 Wall Street was constructed at the same time that buildings on the site were being cleared, due to the builders' time constraints. The old Manhattan Company building was the last to be cleared.[11][65][66] Further, caisson construction could not be used to excavate the site since the existing foundation contained heavy masonry blocks. To ensure that the foundation could adequately support the structure, temporary lighter footings were installed during the demolition of the old buildings and construction of the first 20 stories, and permanent heavy footings were installed afterward.[11][66] In July 1929, the builders held a ceremony where W.A. Starrett, head of the Starrett Corporation, drove the first rivet into the building's column.[29] A $5 million loan was arranged the same month to finance the building.[67]

Work on 40 Wall Street progressed quickly: the site was active 24 hours a day, with 2,300 workers working in three shifts, and interior furnishing progressed as the steel frame rose.[11] The building topped out on November 13, 1929. By that time, the steel frame had reached 900 feet (270 m) above street level, the facade had been completed to the 54th story, and much of the internal furnishing had been completed.[68][69] By December, rental agents Brown, Wheelock, Harris, Vought & Company were leasing out the space at the Chrysler and Manhattan Company buildings, which aggregated 2 million square feet (190,000 m2).[70] Around the time, the 40 Wall Street Corporation was planning to issue $12.5 million in bonds.[71]

The building was completed by May 1, 1930,[66][1][72] and it officially opened on May 26.[31][73] The Manhattan Company took the two basement levels for storage vaults; the first through sixth stories for bank operations; and the 55th floor for its officers' club.[10][31][74] In total, $24 million had been spent on construction.[42] Paul Starrett, of the Starrett Corporation, said that "Of all the construction work which I have handled, the Bank of Manhattan was the most complicated and the most difficult, and I regard it as the most successful."[75][76]

Competition for "world's tallest building" title

In response to 40 Wall Street's completion, the Chrysler's architect William Van Alen obtained permission for a 125-foot (38 m) long spire for the Chrysler Building,[77][78] and had it constructed secretly.[57] The Chrysler Building's spire was completed on October 23, 1929, bringing that building to 1,046 feet (319 m)[79][80] and greatly exceeding 40 Wall Street's height.[81] Disturbed by Chrysler's victory, Shreve & Lamb wrote a newspaper article claiming that their building was the tallest, since it contained the world's highest usable floor. They stated that the observation deck at 40 Wall Street was nearly 100 feet (30 m) above the top floor in the Chrysler Building.[78] 40 Wall Street's observation deck was 836 feet (255 m) while the Chrysler Building's observatory was 783 feet (239 m) high.[82] Afterward, 40 Wall Street was only the tallest building in Lower Manhattan.[18]

John J. Raskob, developer of the Empire State Building (which was also designed by Shreve & Lamb), also wanted to construct the world's tallest building.[83] The "Race into the Sky" was defined by at least five other proposals, although only the Empire State Building would survive the Wall Street Crash of 1929.[84][lower-alpha 4] Plans for the Empire State Building were changed multiple times; the final plan, published in December 1929, called for the building to be 1,250 feet (380 m) tall.[86] The Empire State Building was completed in May 1931, becoming the world's tallest building both by roof height and spire height.[86][87]

Because of late changes to the plans of both 40 Wall Street and the Chrysler Building, as well as the fact that the buildings were erected nearly simultaneously, it is uncertain whether 40 Wall Street was ever taller than the Chrysler Building. The author John Tauranac, who wrote a book about the Empire State Building's history, later stated that if 40 Wall Street had "ever had been the tallest building, they would have had bragging rights, and if they did, I certainly never heard them."[88] If only completed structures are counted, 40 Wall Street was briefly the world's tallest completed building for one month,[18][1] from the first week of May 1930[1] until the opening of the Chrysler Building on May 28, 1930.[57]

Tenancy and foreclosure

40 Wall Street had opened following the Wall Street Crash of 1929 and so suffered from a lack of tenants.[13] Many of the original tenants had withdrawn their commitments to rent space in the building and, in some cases, had gone bankrupt.[14][89][90] As a result, only half of the space in 40 Wall Street was leased during the 1930s,[18][89] Office space rented for $3 per square foot ($32/m2), less than half of the $8 per square foot ($86/m2) that the building's owners had sought.[89][25] For the first five years of the building's existence, the 40 Wall Street Corporation was able to pay the $323,200 interest on the second mortgage-bond issue.[89]

By early 1939, the 40 Wall Street Corporation was falling behind on rent payments, ground leases, and property taxes.[91] That May, the Marine Midland Trust Company started foreclosure proceedings against the 40 Wall Street Corporation after the corporation defaulted on "payments of interest, taxes and other charges".[92] Marine Midland became the trustee of 40 Wall Street's first-mortgage fee and its bonds on the lease in February 1940, supplanting the 40 Wall Street Corporation in that role.[14] Bondholders acquired the building that September in a transaction worth almost $11.5 million.[93] The New York Times later described the building as being "a monument to lost hope" during that era: at the time, the building's $1,000 debentures were being sold at $108.75 apiece.[89] The structure as a whole was worth $1.25 million, less than the 43 elevators inside the building had cost.[89][94]

One of the larger tenants during this time was the Westinghouse Electric and Manufacturing Company, which in 1941 leased four floors.[95] Other tenants included real-estate agents, lawyers, brokers, and bankers,[14][96] and even a short-film theater in 1941.[97] More tenants came during World War II, starting with the United States Department of the Navy.[14][89] By 1943, the building was 80 percent leased, with that rate increasing to 90 percent a year later; 40 Wall Street was completely occupied by the end of the war.[89] Many large tenants such as Prudential Financial, Westinghouse, and Western Union signed long-term leases.[14] After several tenants left during the late 1940s, space in the building was completely rented again in 1951. At the time, 40 Wall Street's office space was renting for $4.22 per square foot ($45.4/m2), a relatively high price for a building without air conditioning.[98]

1946 plane crash

On the evening of May 20, 1946, a United States Army Air Forces Beechcraft C-45F Expediter airplane crashed into 40 Wall Street's northern facade. The twin-engined plane was heading for Newark Airport on a flight originating at Lake Charles Army Air Field in Louisiana. It struck the 58th floor of the building at about 8:10 pm, creating a 20-by-10-foot (6.1 m × 3.0 m) hole in the masonry. The crash killed all five aboard the plane, including a WAC officer, though no one in the building or on the ground was hurt. The fuselage and the wing of the splintered plane fell and caught onto the 12th-story setback, while parts of the aircraft and pieces of brick and mortar from the building fell into the street below. Fog and low visibility were identified as the main causes of the crash, since LaGuardia Field had reported a heavy fog that reduced the ceiling to 500 feet (150 m), obscuring the view of the ground for the pilot at the building's 58th story level.[99][100] The month after the crash, the owners of 40 Wall Street filed a building application with the Department of Buildings to fix the hole in the facade.[25]

This crash was the second of its kind in New York City's history, the first being when an Army B-25 bomber struck the 78th floor of the Empire State Building in July 1945, also caused by fog and poor visibility.[99] The 1946 accident was the last time an airplane accidentally crashed into a building in New York City until the 2006 New York City plane crash on Manhattan's Upper East Side.[101]

1950s through 1970s

Chase Manhattan Bank was created through the merger of the Manhattan Company and Chase National Bank in 1955.[102][103] The new company was headquartered at Chase National's previous building at 20 Pine Street,[21][104] immediately north of 40 Wall Street;[5] soon afterward, Chase constructed a structure at the neighboring 28 Liberty Street to serve as its headquarters.[105] Meanwhile, several offices as well as a bank branch remained in 40 Wall Street.[21] By 1956, the building's financial situation had improved considerably, and the 40 Wall Street Corporation's $1,000 debentures were selling for $1,550.[89] That year, real estate developer William Zeckendorf had his company Webb and Knapp buy the leaseholds for the land from 40 Wall Street Inc., Chase, and the estate of the Iselin family. Webb and Knapp also bought 32% of the 40 Wall Street Corporation's stock.[89][21]

Webb and Knapp became the majority shareholders of the 40 Wall Street Corporation after buying further stock, thereby owning two-thirds of the corporation's shares.[21] The firm attempted to sell 40 Wall Street for $15 million, but a New York Supreme Court judge placed an injunction on the sale in November 1957 after several shareholders claimed the sale was illegal.[106] The corporation's stockholders then voted to sell the building in June 1959.[107] To reduce controversy, a New York Supreme judge ordered that an auction be held to sell off the building.[108] That October, the stockholders held an auction for 40 Wall Street, with a starting price of $17 million.[109] Zeckendorf submitted the highest bid, at $18.15 million, although there was only one other bidder.[108][110][111] At the time, 40 Wall Street was believed to be the most valuable real-estate property to be auctioned.[111] In total, Webb & Knapp had spent $32 million to acquire the building;[21] besides the amount spent toward the auction, the remainder of the cost was used to pay Chase and the Iselin estate.[25]

Webb and Knapp sold the property to the Metropolitan Life Insurance Company in April 1960 for $20 million. Metropolitan Life leased the building back to Webb and Knapp for 99 years, under a leasehold that cost $1.2 million a year.[112] That September, Webb and Knapp sold the leasehold to British investors City & Central Investments for $15 million.[113][114] The sale was finalized in November 1960,[115] and City & Central acquired title that following month.[116] The lower floors were no longer occupied by Chase, which had relocated to its new headquarters at 28 Liberty Street.[21][113] Parts of the interior and exterior were renovated, and the Manufacturers Hanover Corporation took the unoccupied lower stories in 1961.[21][103] City & Central sold the leasehold to Carl M. Loeb, Rhoades Company, 40 Wall Street's largest tenant, five years later.[117][118]

1980s through early 1990s

After Loeb, Rhoades merged with Shearson in 1980, the 251,000 square feet (23,300 m2) of office space occupied by Loeb, Rhoades, was vacated. At the time, 40 Wall Street had 875 square feet (81.3 m2) that was not yet rented, and office space in the Financial District was typically rented for $16 to $20 per square foot ($170 to $220/m2).[119] In 1982, Loeb, Rhoades sold the leasehold to a consortium of investors.[21][120] The same year, the building was purchased by a group of five Germans: Anita, Christian, and Walter Hinneberg; Stephanie von Bismarck; and Joachim Ferdinand von Grumme-Douglas. The Hinneberg siblings collectively held an 80% stake in the building's ownership and the other two investors held a 10% stake each.[120] As part of the ownership agreement, the owners were responsible for the building's upkeep to a certain standard.[121]

The consortium resold the leasehold on December 31, 1982, to Joseph J. and Ralph E. Bernstein for $70 million.[118][122] The Bernstein brothers planned to renovate 40 Wall Street, including gilding its roof.[123] In 1985, the Bernsteins were found to be acting on behalf of Philippine president Ferdinand E. Marcos and his wife Imelda.[124][125][lower-alpha 5] The next year, Marcos was forced out of office and his assets within U.S. banking channels were frozen,[128] and the building's future became uncertain.[121] Capital improvements to the building were suspended while legal proceedings were ongoing; at the time, the building was slated for several improvements, including upgrades to its unreliable elevators.[129][130] A federal judge ordered a foreclosure sale of the Marcos properties in August 1989, and at the court-ordered auction, the Bernsteins submitted the winning bid of $108.9 million; a second mortgage with Citicorp comprised $60 million of this total.[131][132]

The Bernstein brothers could not pay anything else other than the $1.5 million down payment for 40 Wall Street, which led to a second auction in November 1989, where Jack Resnick & Sons submitted the winning bid of $77,000,100.[132][lower-alpha 6] Burton P. Resnick decided to undertake a $50 million renovation of 40 Wall Street the next year.[133] The renovation would have included fire, electrical, and mechanical system replacement; renovation of the lobby; restoration of the facade and windows; and replacement of the elevators.[134] The Resnicks were ultimately able to upgrade the windows.[135]

By the early 1990s, 40 Wall Street was 80 percent vacant.[121][136] In 1991, Citicorp canceled financing for the renovation,[130] citing concerns that the tenants might move out, including banking tenant Manufacturers Hanover.[133] The next year, Manufacturers Hanover moved from the lower stories.[21] Also in 1992, the Hinneberg siblings transferred their 80% ownership stakes to 40 Wall Street Ltd., while Bismarck and Grumme-Douglas conveyed their 20% ownership stakes to Scandic Wall Ltd.[120][137] Citicorp then auctioned off the building in May 1993.[121] The Hong Kong firm Glorious Sun considered buying the building but ultimately decided against it.[138] Another group from Hong Kong, the consortium Kinson Properties, signed a long-term lease for the property in June 1993. Kinson planned to renovate the building for $60 million, including the lobby for $4 million and electrical and mechanical systems for $5-7 million.[121] By the time Kinson sold the leasehold in 1995, little had been done to improve the property.[130]

Trump lease

In July 1995, real estate developer (and later U.S. president) Donald Trump signed a letter of intent to lease the building and renovate it for $100 million.[139] The leasehold was transferred that December. Though The New York Times reported at the time of the sale that Trump purchased the leasehold for $8 million,[140] Trump has given conflicting accounts as to the actual price of 40 Wall Street. In November 1995, Trump stated he was buying the leasehold from Kinson for $100,000.[130] During a 2005 episode of The Apprentice, Trump claimed he only paid $1 million for the leasehold, but that it was actually worth $400 million. Trump's legal advisor, George H. Ross, restated this claim in a 2005 book.[141] On a 2007 episode of CNBC's The Billionaire Inside, Trump again claimed he paid $1 million for the leasehold, but stated the building's value as $600 million. However, in 2012, it was reported that Trump paid $10 million for the leasehold, while the building's estimated worth was $1 billion.[142] Trump's estimate of the building's worth also conflicted with that of New York City tax assessors, who in 2004 estimated the building as being worth $90 million.[143]

Ultimately, Trump spent $35 million on buying and refurbishing 40 Wall Street.[143] Trump planned to convert the upper half of 40 Wall Street to residential space, leaving the bottom half as commercial space.[140] Real-estate experts quoted in the New York Daily News said that the lowest 25 floors were extremely large, and it would not be profitable to convert them to apartments.[130] By 1997, Trump was negotiating with hotels to occupy the lower stories of 40 Wall Street.[144] Der Scutt Architects renovated the lobby,[4] though the cost of converting the upper floors to residential space was ultimately too high for Trump.[145] He tried to sell the building in 2003, expecting offers in excess of $300 million, which did not materialize.[146] The New York Times wrote in 2004 that the building had $145 million of debt.[143] In 2011, Duane Reade opened its flagship branch inside the former banking space.[32][147]

40 Wall Street Ltd. handed its ownership stake in the building to 40 Wall Street Holdings in 2014.[120] According to Federal Election Commission applications filed in 2015 during Trump's 2016 presidential campaign, Trump had an outstanding mortgage of over $50 million on the property.[148] By 2016, Bloomberg News estimated that 40 Wall Street was worth $550 million. At the time, Trump paid $1.65 million a year to the building's owners as part of his lease. According to Bloomberg, several of the building's 21st-century tenants included firms that were accused of scams of fraudulent activity, or were associated with people accused of such activities.[118] Rental income from 40 Wall Street's commercial spaces increased from $30.5 million in 2014 to $43.2 million in 2018.[149] Forbes estimated in 2020 that Trump owed Ladder Capital $138 million for 40 Wall Street as part of a loan that was to come due in 2025.[150] In November 2021, New York prosecutors were scrutinizing several of the Trump Organization's properties for which, between 2011 and 2015, far higher values were presented to potential lenders than were reported to tax officials. The most extreme case involved 40 Wall Street, which in 2012 was cited as being worth $527 million to lenders but only $16.7 million to tax officials.[151]

Critical reception and landmark designations

As Fortune magazine described Ohrstrom in 1930, "His piece de resistance thus far has been the shrewd and able financing of the Manhattan Company Building."[42][152] Two years later, W. Parker Chase wrote that "no building ever constructed more thoroughly typifies the American spirit of hustle than does this extraordinary structure".[12][14][153] In 1960, when 28 Liberty Street was being built, Architectural Forum wrote of 40 Wall Street: "Viewed from the street, the detailing of the top of this middle-aged tower becomes insignificant, but it can be said that the draftsmen in the Severance office, who spent many painstaking hours perfecting the ornamental peak more than three decades ago, have been justified at last."[154]

Not all criticism was positive. Architecture critic Robert A. M. Stern wrote in his 1987 book New York 1930 that 40 Wall Street's proximity to other skyscrapers including 70 Pine Street, 20 Exchange Place, 1 Wall Street, and the Downtown Athletic Club "had reduced the previous generation of skyscrapers to the status of foothills in a new mountain range".[155] Eric Nash wrote in his book Manhattan Skyscrapers that 40 Wall Street's impact was blunted by its location in the middle of the block, "surrealistically situated next to the mighty Greek Revival Federal Hall National Memorial".[28]

On December 12, 1995, the New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission designated 40 Wall Street as a city landmark, noting that the Bank of Manhattan Building was historically significant for being the headquarters of the Manhattan Company and for being part of New York City's 1929–1930 skyscraper race.[156] Five years later, on June 16, 2000, it was added to the National Register of Historic Places,[2] largely for the same reason as the city designation.[34] In 2007, the building was designated as a contributing property to the Wall Street Historic District,[157] a NRHP district.[158]

See also

- List of tallest buildings in New York City

- List of tallest freestanding steel structures

- List of New York City Designated Landmarks in Manhattan below 14th Street

- National Register of Historic Places listings in Manhattan below 14th Street

- Overseas landholdings of the Marcos family

References

Notes

- According to the New York City Department of City Planning, the building contains 63 stories.[7][16]

- Other towers that contain pyramidal roofs include the Metropolitan Life Insurance Company Tower, 14 Wall Street, Woolworth Building, Consolidated Edison Building, and Thurgood Marshall United States Courthouse.[14]

- This distinction excludes structures that were not fully habitable, such as the Eiffel Tower.

- These proposals included the 100-story Metropolitan Life North Building; a 1,050-foot (320 m) tower built by Abraham E. Lefcourt at Broadway and 49th Street; a 100-story tower developed by the Fred F. French Company on Sixth Avenue between 43rd and 44th streets; an 85-story tower to be developed on the site of the Belmont Hotel near Grand Central Terminal; and the Noyes-Schulte Company's proposed tower on Broadway between Duane and Worth streets. Only one of these projects was even partially completed: the base of the Metropolitan Life North Building.[85]

- Marcos was also found to have purchased several other New York City buildings; see Overseas landholdings of the Marcos family.[126] In coded cables between the Marcos Family and their alleged "front" in Manhattan, Gliceria Tantoco, the 40 Wall Street building was referred to using the secret code-word "Bridgetown."[127]

- The Resnicks' bid was just more than the next-highest bid, Citicorp's $77 million bid. Of Resnick's bid, all except the $100 difference were set to go toward the second mortgage with Citicorp.[132]

Citations

- Hoster, Jay (2014). Early Wall Street 1830–1940. Charleston: Arcadia Publishing. p. 127. ISBN 978-1-4671-2263-4. Archived from the original on February 19, 2021. Retrieved June 7, 2018.

- "National Register of Historic Places 2000 Weekly Lists" (PDF). National Park Service. 2000. p. 118. Archived (PDF) from the original on December 28, 2019. Retrieved March 8, 2020.

- "40 Wall Street". CTBUH Skyscraper Center.

- "The Trump Building". Emporis. Archived from the original on February 24, 2012. Retrieved April 26, 2020.

- "NYCityMap". NYC.gov. New York City Department of Information Technology and Telecommunications. Archived from the original on May 24, 2015. Retrieved March 20, 2020.

- National Park Service 2000, p. 2.

- "14 Wall Street, 10005". New York City Department of City Planning. Archived from the original on February 19, 2021. Retrieved September 8, 2020.

- National Park Service 2000, p. 8.

- White, Norval; Willensky, Elliot; Leadon, Fran (2010). AIA Guide to New York City (5th ed.). New York: Oxford University Press. p. 18. ISBN 978-0-19538-386-7.

- Landmarks Preservation Commission 1995, p. 4.

- Landmarks Preservation Commission 1995, p. 5.

- National Park Service 2000, p. 9.

- National Park Service 2000, p. 10.

- Landmarks Preservation Commission 1995, p. 6.

- Robins, Anthony W. (2017). New York Art Deco: A Guide to Gotham's Jazz Age Architecture. Excelsior Editions. State University of New York Press. p. 20. ISBN 978-1-4384-6396-4. OCLC 953576510.

- Deutsche Mortgage & Asset Receiving Corporation (July 20, 2015). "Free Writing Prospectus Structural and Collateral Term Sheet". U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission. Archived from the original on March 31, 2021. Retrieved February 4, 2021.

- "The History of Measuring Tall Buildings". Council on Tall Buildings and Urban Habitat. Archived from the original on April 10, 2012. Retrieved May 3, 2012.

- Stichweh, Dirk (2016). New York Skyscrapers. Prestel Publishing. p. 17. ISBN 978-3-7913-8226-5. OCLC 923852487.

- "Tower Rises 836 Feet; Lofty Observation Floor in Bank of Manhattan Building". The New York Times. June 1, 1930. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on March 31, 2021. Retrieved April 27, 2020.

- National Park Service 2000, p. 4.

- Landmarks Preservation Commission 1995, p. 7.

- National Park Service 2000, pp. 3–4.

- Landmarks Preservation Commission 1995, p. 8.

- "Oceanus Adorns Facade; New Skyscraper for Bank of Manhattan Building Gets Statue". The New York Times. April 26, 1930. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on March 31, 2021. Retrieved March 31, 2021.

- Landmarks Preservation Commission 1995, p. 11.

- Kirstein, Lincoln (1973). Elie Nadelman. Eakins Press. p. 230.

- Landmarks Preservation Commission 1995, pp. 7–8.

- Nash, Eric (2005). Manhattan Skyscrapers. New York: Princeton Architectural Press. p. 59. ISBN 978-1-56898-652-4. OCLC 407907000.

- "Gold Rivet in Building; W.A. Starrett and R.E. Jones Lead Bank of Manhattan Ceremony". The New York Times. July 11, 1929. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on March 31, 2021. Retrieved April 26, 2020.

- National Park Service 2000, p. 5.

- "Manhattan Co. Greets Guests in Skyscraper". Brooklyn Standard Union. May 26, 1930. p. 7. Archived from the original on April 4, 2022. Retrieved April 9, 2020 – via newspapers.com.

- Slotnik, Daniel E. (July 5, 2011). "At Duane Reade's Newest Outpost, Sushi and Hairstyling". City Room. Archived from the original on January 27, 2020. Retrieved April 30, 2020.

- Landmarks Preservation Commission 1995, p. 3.

- National Park Service 2000, p. 7.

- Schulz, Bill (July 29, 2016). "Hamilton, Burr and the Great Waterworks Ruse". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on October 30, 2019. Retrieved April 30, 2020.

- The Commercial and Financial Chronicle. National News Service. 1920. p. 265. Archived from the original on March 31, 2021. Retrieved January 10, 2020.

- "G. L. Ohrstrom, Financier, Dead; Industrialist and Horseman Downed Last German Plane in World War I Combat". The New York Times. November 11, 1955. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on March 31, 2021. Retrieved April 26, 2020.

- "Banker at 34 to Build Highest Structure Here". New York Herald Tribune. April 10, 1929. p. 14. ProQuest 1111573382. Archived from the original on March 31, 2021. Retrieved March 27, 2021 – via ProQuest.

- Levinson 1961, p. 230.

- Landmarks Preservation Commission 1995, p. 9.

- "Manhattan Company". The Skyscraper Museum. Archived from the original on March 31, 2021. Retrieved April 26, 2020.

- Landmarks Preservation Commission 1995, p. 2.

- "Among the Millions". New York Daily News. September 8, 1928. p. 74. Archived from the original on April 4, 2022. Retrieved April 26, 2020 – via newspapers.com.

- "Wall St. Building in Long Leasehold to Cost $2,000,000". Brooklyn Daily Eagle. September 9, 1928. p. 25. Archived from the original on August 3, 2021. Retrieved April 24, 2020 – via Brooklyn Public Library; newspapers.com.

- "O'donnell Resells Seventh Av. Corner; Operator Disposes of the Hotel Grenoble at Fifty-sixth Street". The New York Times. December 6, 1928. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on March 31, 2021. Retrieved April 26, 2020.

- "45-story Building for Wall Street". New York Daily News. December 16, 1928. p. 45. Retrieved April 26, 2020 – via newspapers.com.

- "$12,500,000 Sought for New Skyscraper; Forty Wall Street Corporation Plans Bond Issue for 70-Story Building". The New York Times. January 14, 1930. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on March 31, 2021. Retrieved April 26, 2020.

- "47-Story Building to Rise in Wall St.; Plans Filed for Structure to Be Erected Next to Sub-Treasury at Cost of $3,300,000". The New York Times. March 2, 1929. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on March 31, 2021. Retrieved April 26, 2020.

- "25 Pine Street is Sold; Ohrstrom Syndicate Adds to Site for Skyscraper. Herald Tribune Plant Plans Filed Aero Underwriters Lease Space". The New York Times. March 7, 1929. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on March 31, 2021. Retrieved April 26, 2020.

- Gray, Christopher (November 15, 1992). "Streetscapes: 40 Wall Street; A Race for the Skies, Lost by a Spire". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on November 7, 2017. Retrieved November 3, 2017.

- "Revising Skyscraper Plan; Wall Street Building May Go Up Sixty-four Stories". The New York Times. April 8, 1929. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on March 31, 2021. Retrieved April 26, 2020.

- "Wall St. Building to Top All in World; 840-Foot Bank of Manhattan Structure to Rise 48 Feet Above Woolworth Tower". The New York Times. April 10, 1929. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on March 31, 2021. Retrieved April 26, 2020.

- "Ohrstrom Plans Tallest Building". Brooklyn Daily Eagle. April 10, 1929. p. 23. Archived from the original on August 3, 2021. Retrieved April 26, 2020 – via Brooklyn Public Library; newspapers.com.

- "Building Record Claimed; Starrett Brothers Also See Occupancy Record in 40 Wall Street". The New York Times. April 25, 1930. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on March 31, 2021. Retrieved April 28, 2020.

- "The Manhattan Company – Skyscraper.org; "...'race' to erect the tallest tower in the world."". Skyscraper.org. Archived from the original on May 15, 2015. Retrieved September 27, 2010.

- Rasenberger, Jim (2009). High Steel: The Daring Men Who Built the World's Greatest Skyline, 1881 to the Present. HarperCollins. pp. 388–389. ISBN 978-0-06-174675-8. Archived from the original on July 29, 2020. Retrieved December 28, 2017.

- Tauranac 2014, p. 130.

- "Denies Altering Plans for Tallest Building; Starrett Says Height of Bank of Manhattan Structure Was Not Increased to Beat Chrysler". The New York Times. October 20, 1929. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on March 31, 2021. Retrieved April 26, 2020.

- "Razing Buildings on Wall Street; Ten Tall Office Structures Are Being Torn Down for Two High Banking Edifices". The New York Times. May 12, 1929. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on June 16, 2018. Retrieved April 27, 2020.

- "Skyscraper Cost Set at Low of $9,000,000; Minimum Figure Placed in Lease of Bank of Manhattan Site in Wall Street". The New York Times. May 12, 1929. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on March 31, 2021. Retrieved April 26, 2020.

- "$8,501,000 Is Top Bid for Assay Office; Ohrstrom Interests Make the Highest Offer to Government for Wall Street Landmark". The New York Times. June 26, 1929. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on March 31, 2021. Retrieved April 26, 2020.

- "Syndicate Bids U.S. Property in Wall Street". Brooklyn Citizen. June 26, 1929. p. 5. Archived from the original on April 4, 2022. Retrieved April 26, 2020 – via newspapers.com.

- "Gets Assay Office Site". Brooklyn Times-Union. June 26, 1929. p. 53. Retrieved April 24, 2020 – via newspapers.com.

- "The Historic Assay Office Plot". Brooklyn Daily Eagle. July 23, 1929. p. 18. Archived from the original on August 3, 2021. Retrieved April 26, 2020 – via Brooklyn Public Library; newspapers.com.

- Fortune 1930, pp. 33–35.

- "The Manhattan Company Building, New York City". Architecture and Building. Vol. 62. July 1930. p. 193.

- "Review of the Day in Realty Market; Few Sales Reported as Important Leasehold and Mortgage Deals Are Announced". The New York Times. July 16, 1929. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on March 31, 2021. Retrieved April 26, 2020.

- "Steel Construction Completed on Bank of Manhattan Building". Brooklyn Citizen. November 13, 1929. p. 7. Archived from the original on April 4, 2022. Retrieved April 26, 2020 – via newspapers.com.

- "Bank Building Speeded; Observation Tower at 40 Wall St. to Be 845 Feet Up". The New York Times. November 17, 1929. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on March 31, 2021. Retrieved April 27, 2020.

- "Renting Keeps Pace With Building Record; Brokers Contract to Find Tenants for 2,000,000 Square Feet in Two Skyscrapers". The New York Times. December 29, 1929. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on March 13, 2018. Retrieved April 27, 2020.

- "$12,500,000 Sought for New Skyscraper; Forty Wall Street Corporation Plans Bond Issue for 70Story Building". The New York Times. January 14, 1930. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on March 31, 2021. Retrieved April 27, 2020.

- "Bank of Manhattan Built in Record Time; Structure 927 Feet High, Second Tallest in World, Is Erected in Year of Work". The New York Times. May 6, 1930. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on March 31, 2021. Retrieved April 27, 2020.

- "New Home Today for Manhattan Co.; Federal, State and City Officials to Join in Formal Opening of the 71-Story Structure". The New York Times. May 26, 1930. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on March 31, 2021. Retrieved April 27, 2020.

- "Manhattan Company Opens New Main Offices". The Bankers Magazine. Vol. 120. 1930. pp. 905–906, 916. Archived from the original on March 31, 2021. Retrieved October 3, 2020.

- Starrett, Paul (1938). Changing the Skyline: An Autobiography. Whittlesey house. p. 283. Archived from the original on March 31, 2021. Retrieved October 3, 2020.

- Landmarks Preservation Commission 1995, pp. 5–6.

- Stravitz 2002, p. 161.

- Binders, George (2006). 101 of the World's Tallest Buildings. Images Publishing Group. p. 102. ISBN 978-1-86470-173-9. Archived from the original on July 29, 2020. Retrieved December 28, 2017.

- Curcio, V. (2001). Chrysler: The Life and Times of an Automotive Genius. Automotive History and Personalities. Oxford University Press. p. 426. ISBN 978-0-19-514705-6.

- Cobb, H.M. (2010). The History of Stainless Steel. Asm Handbook. ASM International. p. 110. ISBN 978-1-61503-011-8. Archived from the original on July 29, 2020. Retrieved December 28, 2017.

- Willis, Carol; Friedman, Donald (1998). Building the Empire State. New York: W.W. Norton. p. 14. ISBN 978-0-393-73030-2.

- "Tower Rises 836 Feet; Lofty Observation Floor in Bank of Manhattan Building". The New York Times. June 1, 1930. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on March 31, 2021. Retrieved April 27, 2020.

- Tauranac 2014, p. 131.

- Stern, Gilmartin & Mellins 1987, p. 612.

- Stern, Gilmartin & Mellins 1987, pp. 610, 612.

- Tauranac 2014, p. 185.

- "Empire State Tower, Tallest In World, Is Opened By Hoover; The Highest Structure Raised By The Hand Of Man". The New York Times. May 2, 1931. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on March 31, 2021. Retrieved March 31, 2021.

- Pollak, Michael (September 24, 2010). "Tall Towers and Sharp Razors". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on February 2, 2018. Retrieved April 30, 2020.

- "40 Wall Enjoys Its Bad Memories; Skyscraper's Owners, Now Riding High, Recall Hard Times With Pleasure Recalls Bad Old Days". The New York Times. September 23, 1956. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on February 19, 2021. Retrieved April 28, 2020.

- Levinson 1961, p. 231.

- "Use Bond Security on 40 Wall Street; Trustees Report Foreclosure Likely for Downtown Bank Skyscraper". The New York Times. May 10, 1939. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on March 31, 2021. Retrieved April 28, 2020.

- "Start Foreclosure on 40 Wall Street; Trustee Presents Reorganization Plan for Skyscraper". The New York Times. May 25, 1939. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on February 4, 2021. Retrieved March 31, 2021.

- "Bondholders Acquire 40 Wall Street Building On Bid of $11,489,500 in Reorganization Plan". The New York Times. September 26, 1940. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on March 31, 2021. Retrieved March 31, 2021.

- Abramson, Daniel M. (2001). Skyscraper Rivals: the AIG Building and the Architecture of Wall Street. Princeton Architectural Press. p. 29. ISBN 9781568982441.

- "Takes Four Floors in 40 Wall Street; Westinghouse Company Will Move Three Divisions Into Downtown Quarters". The New York Times. February 26, 1941. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on March 31, 2021. Retrieved April 28, 2020.

- "40 Wall Street Adds and Extends Tenants; Linen Importer Rents Store and Basement on Fifth Ave". The New York Times. May 16, 1941. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on February 26, 2018. Retrieved April 28, 2020.

- "Movies Used for Renting; Features of Wall Street Offices Shown in Fifteen Minutes". The New York Times. April 15, 1941. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on March 9, 2021. Retrieved April 28, 2020.

- "All Space Taken at 40 Wall Street; Lease on 66th Floor Completes Renting of Seventy-Story Downtown Skyscraper". The New York Times. September 26, 1951. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on March 8, 2021. Retrieved April 28, 2020.

- "Pilot Lost in Fog; Scene of Plane Crash Last Night Airplane Crashes Into Skyscraper". The New York Times. May 21, 1946. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on February 16, 2020. Retrieved April 27, 2020.

- Moore, William (May 21, 1946). "Plane Hits Wall St. Bank". Chicago Tribune. p. 1. Archived from the original on August 3, 2021. Retrieved April 26, 2020 – via Chicago Tribune; newspapers.com.

- Levy, Matthys; Salvadori, Mario (2002). Why Buildings Fall Down: How Structures Fail. Norton – Library of Congress visual sourcebooks in architecture, design, and engineering. W.W. Norton. p. 30. ISBN 978-0-393-31152-5.

no plane has accidentally hit a skyscraper since the Empire State and Wall Street catastrophes

- "Chase and Manhattan Holders Approve Merger by Big Margin". The New York Times. March 29, 1955. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on November 3, 2020. Retrieved April 28, 2020.

- National Park Service 2000, p. 11.

- "Chase Bank Buys Nassau St. Block". The New York Times. February 24, 1955. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on March 31, 2021. Retrieved March 31, 2021.

- "One Chase Manhattan Plaza" (PDF). New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission. February 10, 2009. p. 1. Archived (PDF) from the original on December 23, 2016. Retrieved February 17, 2020.

- "Court Enjoins Sale of 40 Wall Street". The New York Times. November 9, 1957. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on March 8, 2021. Retrieved April 28, 2020.

- "Sale of 40 Wall Street Voted by Stockholders". The New York Times. June 24, 1959. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on February 19, 2021. Retrieved April 28, 2020.

- "$18,150,000 Buys Wall Street Building". Press and Sun-Bulletin. October 28, 1959. p. 8. Retrieved April 28, 2020 – via newspapers.com.

- "Fourth Tallest Building Will Be Auctioned Here". The New York Times. October 26, 1959. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on February 19, 2021. Retrieved April 28, 2020.

- Stern, Walter H. (October 28, 1959). "70-story Building Brings $18,150,000; Zeckendorf, One of the Two Bidders, Buys 40 Wall St. in Tense Auction Sale". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on March 31, 2021. Retrieved April 28, 2020.

- "A Tall Story About $18,150,000". Brooklyn Daily. October 29, 1959. p. 3. Archived from the original on September 15, 2020. Retrieved April 28, 2020 – via newspapers.com.

- Stern, Walter H. (April 29, 1960). "40 Wall St. Sold by Webb & Knapp; Metropolitan Life Acquires Building for $20,000,000 and Leases It Back". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on March 31, 2021. Retrieved April 28, 2020.

- Fowler, Glenn (September 13, 1960). "British Firm Buys 40 Wall St. Lease; London Concern Expected to Pay $15,000,000 to Zeckendorf for It". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on March 31, 2021. Retrieved April 28, 2020.

- "Briton Leases Wall St. Building". Glens Falls Post-Star. September 13, 1960. p. 1. Archived from the original on April 4, 2022. Retrieved April 28, 2020 – via newspapers.com.

- "40 Wall St. in Deal; Webb & Knapp to Sell Lease to British Interests". The New York Times. November 12, 1960. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on March 8, 2021. Retrieved April 28, 2020.

- "40 Wall St. Lease Shifted". The New York Times. December 2, 1960. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on February 19, 2021. Retrieved April 28, 2020.

- Porterfield, Byron (June 13, 1966). "Leasehold of 71-Story Building In the Financial District Is Sold; 40 Wall St. Property Bought by Tenant and Associates From British Group". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on March 31, 2021. Retrieved April 28, 2020.

- Faux, Zeke; Abelson, Max (June 22, 2016). "Inside Trump's Most Valuable Tower: Felons, Dictators and Girl Scouts". Bloomberg. Archived from the original on April 27, 2020. Retrieved April 30, 2020.

- Oser, Alan S. (April 16, 1980). "Real Estate; Realigning Tenants at 40 Wall St". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on March 31, 2021. Retrieved April 29, 2020.

- Putzier, Konrad (January 6, 2017). "Meet the obscure German magnates who actually own Trump's most valuable building". The Real Deal. Archived from the original on March 31, 2021. Retrieved January 6, 2017.

- Oser, Alan S. (June 20, 1993). "Perspectives: 40 Wall Street; Asian Buyer Accepts a Leasing Challenge". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on November 10, 2019. Retrieved April 26, 2020.

- Fowler, Glenn (January 5, 1983). "Landmark At 40 Wall Is Sold;". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on July 31, 2015. Retrieved April 28, 2020.

- Goncharoff, Katya (August 12, 1984). "The Glitter of Gold Gains in Facade and Lobby Door Some Owners Say Gilding May Enhance Values". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on March 31, 2021. Retrieved April 29, 2020.

- Gottlieb, Martin (December 17, 1985). "2 Cited by House Panel Are Active in Real Estate". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on November 25, 2017. Retrieved April 29, 2020.

- "Men admit they made land deals for Marcos". Press and Sun-Bulletin. April 10, 1986. p. 6. Archived from the original on April 4, 2022. Retrieved April 28, 2020 – via newspapers.com.

- Perlez, Jane (March 6, 1986). "Manila Under Aquino: Lawyers Joust in Manhattan; Manila Wins Round with Marcos in New York Court". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on May 24, 2015. Retrieved April 29, 2020.

- Russakoff, Dale (March 30, 1986). "The Philippines: Anatomy of a Looting". The Washington Post. ISSN 0190-8286. Archived from the original on August 25, 2020. Retrieved August 4, 2020.

- Pace, Eric (March 4, 1986). "Marcos Holdings Frozen by Judge". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on May 24, 2015. Retrieved April 29, 2020.

- McCain, Mark (November 27, 1988). "Commercial Property: Elevator Service; Vertical Commuters Growing Less Tolerant of Delays". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on February 1, 2018. Retrieved April 29, 2020.

- "New Trump buy is a tall order". New York Daily News. November 13, 1995. p. 40. Archived from the original on April 4, 2022. Retrieved April 30, 2020 – via newspapers.com.

- "Marcos Holdings Shedding Web of Intrigue". The New York Times. August 20, 1989. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on April 27, 2020. Retrieved April 29, 2020.

- Donovan, Roxanne (November 14, 1989). "$100 extra wins bargain building". New York Daily News. p. 571. Archived from the original on April 4, 2022. Retrieved April 28, 2020 – via newspapers.com.

- Dunlap, David W. (November 10, 1991). "Commercial Property: 40 Wall Street; Citicorp Aborts $50 Million Financing of Renovation". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on November 7, 2017. Retrieved November 7, 2017.

- Lyons, Richard D. (January 10, 1990). "Real Estate; Sprucing Up Marcos Gem On Wall St". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on October 4, 2019. Retrieved April 29, 2020.

- National Park Service 2000, p. 11.

- Pacelle, Mitchell (June 11, 1992). "Skyline Turning Hollow Near Wall Street: Vacancies Rise in Old Downtown New York Towers". Wall Street Journal. p. A2. ISSN 0099-9660. ProQuest 135555688.

- Craig, Susanne (August 20, 2016). "Trump's Empire: A Maze of Debts and Opaque Ties". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on May 6, 2020. Retrieved April 29, 2020.

- Henry, David (July 18, 1994). "Overseas Chinese' money pours into high profile Manhattan real estate". Newsday. pp. 73, 76, 77. Archived from the original on February 20, 2022. Retrieved February 20, 2022.

- Slatin, Peter (July 12, 1995). "About Real Estate; Trump to Buy Leasehold At 40 Wall St". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on March 31, 2021. Retrieved April 29, 2020.

- Bloomberg Business News (December 7, 1995). "40 Wall Street Is Sold to Trump". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on November 7, 2017. Retrieved November 7, 2017.

- Ross, George H. (2005). Trump Strategies for Real Estate: Billionaire Lessons for the Small Investor. John Wiley & Sons. p. 50. ISBN 978-0-471-73643-1.

- "Trump fills 40 Wall Street with low rents, incentives". The Real Deal. January 23, 2012. Archived from the original on September 26, 2015. Retrieved April 26, 2020.

- O'Brien, Timothy L. (October 23, 2005). "What's He Really Worth?". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on February 25, 2016. Retrieved April 30, 2020.

- Halbfinger, David M. (May 28, 1997). "Trump's Bank Making Deal He Declined". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on December 28, 2017. Retrieved April 29, 2020.

- Ross, George H. (2005). Trump Strategies for Real Estate: Billionaire Lessons for the Small Investor. John Wiley & Sons. p. 51. ISBN 978-0-471-73643-1.

- "40 Wall Street | TRD Research". therealdeal.com. Archived from the original on April 10, 2020. Retrieved April 26, 2020.

- Kadet, Anne (August 20, 2011). "Yes, It's Still A Drugstore". Wall Street Journal. ISSN 0099-9660. Archived from the original on May 16, 2019. Retrieved April 30, 2020.

- Zurcher, Anthony (July 23, 2015). "Five take-aways from Donald Trump's financial disclosure". BBC. Archived from the original on January 24, 2016. Retrieved March 2, 2016.

- Buettner, Russ; Craig, Susanne; McIntire, Mike (September 27, 2020). "Trump's Taxes Show Chronic Losses and Years of Income Tax Avoidance". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on September 27, 2020. Retrieved October 18, 2020.

- Alexander, Dan. "Donald Trump Has At Least $1 Billion In Debt, More Than Twice The Amount He Suggested". Forbes. Archived from the original on January 15, 2021. Retrieved October 18, 2020.

- Fahrenthold, David A.; O'Connell, Jonathan; Dawsey, Josh; Jacobs, Shayna (November 22, 2021). "N.Y. prosecutors set sights on new Trump target: Widely different valuations on the same properties". The Washington Post. ISSN 0190-8286. Archived from the original on November 23, 2021. Retrieved November 28, 2021.

- Fortune 1930, p. 13.

- Chase, W. Parker (1983) [1932]. New York, the Wonder City. New York: New York Bound. p. 157. ISBN 978-0-9608788-2-6. OCLC 9946323. Archived from the original on April 15, 2021. Retrieved April 15, 2021.

- "The Chase: portrait of a giant" (PDF). Architectural Forum. Vol. 115, no. 1. July 1961. pp. 84 (PDF 62). Archived (PDF) from the original on February 28, 2020. Retrieved May 3, 2020.

- Stern, Gilmartin & Mellins 1987, p. 603.

- Landmarks Preservation Commission 1995, p. 1.

- "Wall Street Historic District" (PDF). National Register of Historic Places, National Park Service. February 20, 2007. pp. 4–5. Archived (PDF) from the original on February 19, 2021. Retrieved February 9, 2021.

- "National Register of Historic Places 2007 Weekly Lists" (PDF). National Park Service. 2007. p. 65. Archived (PDF) from the original on December 28, 2019. Retrieved July 20, 2020.

Sources

- Bascomb, Neal (2003). Higher: A Historic Race to the Sky and the Making of a City. Doubleday. ISBN 978-0-385-50661-8.

- Historic Structures Report: Manhattan Company Building (PDF) (Report). National Register of Historic Places, National Park Service. June 16, 2000.

- Levinson, Leonard L. (1961). Wall Street: A Pictorial History. Ziff-Davis.

- Manhattan Company Building (PDF) (Report). New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission. December 12, 1995.

- Stravitz, David (2002). The Chrysler Building: Creating a New York Icon Day by Day. Princeton Architectural Press. ISBN 1-56898-354-9.

- Stern, Robert A. M.; Gilmartin, Patrick; Mellins, Thomas (1987). New York 1930: Architecture and Urbanism Between the Two World Wars. New York: Rizzoli. ISBN 978-0-8478-3096-1. OCLC 13860977.

- Tauranac, John (2014). The Empire State Building: The Making of a Landmark. Scribner. ISBN 978-0-684-19678-7.

- "The skyscraper". Fortune; American Institute of Steel Construction. 1930 – via HathiTrust Digital Library.

External links

- 40 Wall Street on The Trump Organization's website

- The Trump Building on CTBUH Skyscraper Center

- Wired New York – 40 Wall Street (The Trump Building)

- in-Arch.net: The 40 Wall Street

- "Emporis building ID 115941". Emporis. Archived from the original on November 2, 2015.