Theobald von Bethmann Hollweg

Theobald Theodor Friedrich Alfred von Bethmann Hollweg (29 November 1856 – 1 January 1921) was a German politician who was the chancellor of the German Empire from 1909 to 1917. He oversaw the German entry into World War I. According to biographer Konrad H. Jarausch, a primary concern for Bethmann in July 1914 was the steady growth of Russian power, and the growing closeness of the British and French military collaboration. Under these circumstances he decided to run what he considered a calculated risk to back Vienna in a local small-scale war against Serbia, while risking a major war with Russia. He calculated that France would not support Russia. It failed when Russia decided on general mobilization, and his own army demanded the opportunity to use the Schlieffen Plan for quick victory against a poorly prepared France. By rushing through Belgium, Germany expanded the war to include the United Kingdom. Bethmann thus failed to keep France and Britain out of the conflict, which became the First World War.[1]

Theobald von Bethmann Hollweg | |

|---|---|

.jpg.webp) Bethman Hollweg in 1914 | |

| Chancellor of the German Empire Minister President of Prussia | |

| In office 14 July 1909 – 13 July 1917 | |

| Monarch | Wilhelm II |

| Preceded by | Bernhard von Bülow |

| Succeeded by | Georg Michaelis |

| Vice-Chancellor of the German Empire Secretary of State of the Interior | |

| In office 24 June 1907 – 10 July 1909 | |

| Chancellor | Bernhard von Bülow |

| Preceded by | Arthur von Posadowsky-Wehner |

| Succeeded by | Clemens von Delbrück |

| Personal details | |

| Born | Theobald Theodor Friedrich Alfred von Bethmann Hollweg 29 November 1856 Hohenfinow, Kingdom of Prussia |

| Died | 1 January 1921 (aged 64) Hohenfinow, Weimar Republic |

| Political party | Independent |

| Signature | |

Ancestry

Bethmann Hollweg was born in Hohenfinow, Brandenburg, the son of Prussian official Felix von Bethmann Hollweg. His grandfather was August von Bethmann-Hollweg, who had been a prominent law scholar, president of Frederick William University in Berlin, and Prussian Minister of Culture. His great-grandfather was Johann Jakob Hollweg, who had married a daughter of the wealthy Frankfurt am Main banking family of Bethmann, founded in 1748.[2]

His mother, Isabella de Rougemont, was a French Swiss. His grandmother was Auguste Wilhelmine Gebser of the Prussian noble family of Gebesee. Cousin of philosopher Jean Gebser and film producer Paul Gebser Beahan.

Early life

He was educated at the boarding school of Schulpforta and at the Universities of Strasbourg, Leipzig and Berlin. Entering the Prussian administrative service in 1882, Bethmann Hollweg rose to the position of the President of the Province of Brandenburg in 1899. He married Martha von Pfuel, the niece of Ernst von Pfuel, Prime Minister of Prussia. From 1905 to 1907, Bethmann Hollweg served as Prussian Minister of the Interior and then as Imperial State Secretary for the Interior from 1907 to 1909. On the resignation of Chancellor Bernhard von Bülow in 1909, Bethmann Hollweg was appointed to succeed him.[3]

Chancellor

.jpg.webp)

Early term

In foreign policy he pursued a policy of détente with the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland, hoping to come to some agreement that would put a halt to the two countries' ruinous naval arms race and give Germany a free hand to deal with France. The policy failed, largely from the opposition of German Naval Minister Alfred von Tirpitz.

Despite the increase in tensions because of the Second Moroccan Crisis of 1911, Bethmann Hollweg improved relations with Britain to some extent, working with British Foreign Secretary Sir Edward Grey to alleviate tensions during the Balkan Wars of 1912–1913. He did not learn of the Schlieffen Plan until December 1912, after he had received the Second Haldane Mission.[4] He negotiated treaties over an eventual partition of the Portuguese colonies and the projected Berlin-Baghdad railway, the latter aimed in part at securing Balkan countries' support for a German-Ottoman alliance.

The crisis came to a head on 5 July 1914 when the Hoyos Mission arrived in Berlin in response to Austro-Hungarian Foreign Minister Leopold Berchtold's plea for friendship. Bethmann Hollweg was assured that Britain would not intervene in the frantic diplomatic rounds across the European powers. However, reliance on that assumption encouraged Austria to demand Serbian concessions. His main concern was Russian border manoeuvres, conveyed by his ambassadors at a time when Raymond Poincaré himself was preparing a secret mission to St Petersburg. He wrote to Count Sergey Sazonov, "Russian mobilisation measures would compel us to mobilise and that then European war could scarcely be prevented."[5]

When War Minister Erich von Falkenhayn wanted to mobilise for war on 29 July, Bethmann was still against it but used his veto to prevent the Reichstag from debating it. Pourtales' telegram of 31 July was what Helmuth von Moltke the Younger, who declared a Zustand drohender Kriegsgefahr (state of imminent danger of war), wanted to hear; to Bethmann Hollweg's dismay, the other powers had failed to communicate Russia's provocation.

In domestic politics, Bethmann Hollweg's record was also mixed, and his compromising of socialists and liberals on the left and nationalists on the right alienated most of the German political establishment.

World War I

Following the assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand in Sarajevo on 28 June 1914, Bethmann Hollweg and Germany's foreign minister, Gottlieb von Jagow, were instrumental in assuring Austria-Hungary of Germany's unconditional support, regardless of its actions against the Serbia. While Grey was suggesting a mediation between Austria-Hungary and Serbia, Bethmann Hollweg wanted Austria-Hungary to attack Serbia, and so he tampered with the British message and deleted the last line of the letter:

Also, the whole world here is convinced, and I hear from my colleagues that the key to the situation lies in Berlin, and that if Berlin seriously wants peace, it will prevent Vienna from following a foolhardy policy.[6]

When the Austro-Hungarian ultimatum was presented to Serbia, Kaiser Wilhelm II ended his cruise of the North Sea and hurried back to Berlin.

When Wilhelm arrived at the Potsdam station late in the evening of July 26, he was met by a pale, agitated, and somewhat fearful Chancellor. Bethmann Hollweg's apprehension stemmed not from the dangers of the looming war, but rather from his fear of the Kaiser's wrath when the extent of his deceptions were revealed. The Kaiser's first words to him were suitably brusque: "How did it all happen?" Rather than attempt to explain, the Chancellor offered his resignation by way of apology. Wilhelm refused to accept it, muttering furiously, "You've made this stew, now you're going to eat it!"[7]

Despite his belief that war was inevitable, Bethmann Hollwegg avoided openly mobilizing the Imperial German Army until after Tsar Nicholas II had mobilized the Imperial Russian Army. This allowed the German government to claim it was the victim of Russian aggression, and also won it the support of the anti-Tsarist Social Democratic Party of Germany for most of the war.[8]

Bethmann Hollweg, much of whose foreign policy before the war had been guided by his desire to establish good relations with Britain, was particularly upset by the British entry into the war following the German violation of Belgium's neutrality during its invasion of France. He reportedly asked the departing British Ambassador Edward Goschen how Britain could go to war over a "scrap of paper" ("ein Fetzen Papier"), which was the 1839 Treaty of London guaranteeing Belgium's neutrality.

Bethmann Hollweg had made some plans in the event Britain came into the war and was involved closely in the plans to destabilise the British Empire's colonies, most notably the Hindu–German Conspiracy.

A tall, gaunt, sombre, well-trimmed aristocratic figure, Bethmann Hollweg sought approval from a declaration of war. His civilian colleagues pleaded for him to register some febrile protest, but he was frequently outflanked by the military leaders, who played an increasingly important role in the direction of all German policy.[10] However, according to historian Fritz Fischer, writing in the 1960s, Bethmann Hollweg made more concessions to the nationalist right than had previously been thought. He supported the ethnic cleansing of Poles from the Polish Border Strip as well as Germanisation of Polish territories by settlement of German colonists.[11]

Bethmann was against Erich von Falkenhayn and wanted Erich Ludendorff as the chief of staff.[12]

Bethmann presented the Septemberprogramm, which was a survey of ideas from the elite should Germany win the war. Bethmann Hollweg, with all credibility and power now lost, conspired over Falkenhayn's head with Paul von Hindenburg and Erich Ludendorff (respectively commander-in-chief and chief of staff for the Eastern Front in the Oberste Heeresleitung) for an Eastern Offensive. They then succeeded, in August 1916 in securing Falkenhayn's replacement by Hindenburg as Chief of the General Staff, with Ludendorff as First Quartermaster-General (Hindenburg's deputy). Thereafter, Bethmann Hollweg's hopes for US President Woodrow Wilson's mediation at the end of 1916 came to nothing. Over Bethmann Hollweg's objections, Hindenburg and Ludendorff forced the adoption of unrestricted submarine warfare in March 1917, adopted as a result of Henning von Holtzendorff's memorandum. Bethmann Hollweg had been a reluctant participant and opposed it in cabinet. The US entered the war in April 1917, perhaps the inevitability that they had wished to avoid.

Downfall

Bethmann Hollweg remained in office until July 1917, but during the war lost political influence to the Oberste Heeresleitung under Paul von Hindenburg and Erich Ludendorff. Despite his involvement in the Septemberprogramm, he increasingly favored a negotiated peace to end the conflict. This position was unpopular in the Reichstag, which included many pan-German nationalists who demanded annexations and formed the German Fatherland Party under Alfred von Tirpitz. However, Bethmann Hollweg believed that if the Allied powers accepted a German peace offer could win the support of the Social Democrats and seek the United States as a mediator to end the war on fair terms.[13]

In December 1916, shortly after Woodrow Wilson was reelected in the 1916 United States presidential election and David Lloyd George replaced H. H. Asquith as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom, Bethmann Hollweg announced that the Central Powers would accept a negotiated peace. The Allied governments refused the offer, but the United States was interested in mediating the conflict and pressured the British government into accepting mediation. Then in January 1917 Ludendorff pressured Bethmann Hollweg into accepting a Catholic Centre Party resolution allowing the Imperial German Navy to resume unrestricted submarine warfare, ruining relations with the United States. The resumption of U-boat attacks on American shipping and the leak of the Zimmermann Telegram led to the American entry into World War I in March 1917.[13]

After the February Revolution forced the abdication of Tsar Nicholas II in Russia, Bethmann Hollweg began to worry about a similar anti-monarchist revolution in Germany. He convinced Kaiser Wilhelm II to include vague promises of political reform in his Easter address. This attracted great interest from the Social Democratic, Catholic Centre, and Progressive Parties. The Reichstag passed Matthias Erzberger's Reichstag Peace Resolution demanding an end to the war and political reforms. Ludendorff convinced the Kaiser that Bethmann Hollweg was endangering the German monarchy and forced him to resign. He was replaced by a relatively unknown figure, Georg Michaelis, who watered down the final Peace Resolution.[13]

According to Wolfgang J. Mommsen, Bethmann Hollweg weakened his own position by failing to establish good control over public relations. To avoid highly intensive negative publicity, he conducted much of his diplomacy in secret, thereby failed to build strong support for it. In 1914 he was willing to risk a world war to win public support.[14]

Cabinet

| Cabinet (1909–1917) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Office | Incumbent | In office | Party |

| Chancellor | Theobald von Bethmann Hollweg | 14 July 1909 – 13 July 1917 | None |

| Vice-Chancellor of Germany Secretary for the Interior |

Clemens von Delbrück | 14 July 1909 – 22 May 1916 | None |

| Karl Helfferich | 22 May 1916 – 23 October 1917 | None | |

| Secretary for the Foreign Affairs | Wilhelm von Schoen | 7 October 1907 – 28 June 1910 | None |

| Alfred von Kiderlen-Waechter | 28 June 1910 – 30 December 1912 | None | |

| Gottlieb von Jagow | 30 December 1912 – 22. November 1916 | None | |

| Arthur Zimmermann | 22 November 1916 – 6 August 1917 | None | |

| Secretary for the Justice | Rudolf Arnold Nieberding | 10 July 1893 – 25 October 1909 | None |

| Hermann Lisco | 25 October 1909 – 5 August 1917 | None | |

| Secretary for the Treasury | Adolf Wermuth | 14 July 1909 – 16 March 1912 | None |

| Hermann Kühn | 16 March 1912 – 31 January 1915 | None | |

| Karl Helfferich | 31 January 1915 – 22 May 1916 | None | |

| Siegfried von Roedern | 22 May 1916 – 13 November 1918 | None | |

| Secretary for the Post | Reinhold Kraetke | 6 May 1901 – 5 August 1917 | None |

| Secretary for the Navy | Alfred von Tirpitz | 18 June 1897 – 15 March 1916 | None |

| Eduard von Capelle | 15 March 1916 – 5 October 1918 | None | |

| Secretary for the Colonies | Bernhard Dernburg | 17 May 1907 – 9 June 1910 | None |

| Friedrich von Lindequist | 10 June 1910 – 3 November 1911 | None | |

| Wilhelm Solf | 20 November 1911 – 13 December 1918 | None | |

| Secretary for Food | Adolf Tortilowicz von Batocki-Friebe | 26 May 1916 – 6 August 1917 | None |

German Revolution

During 1918, German support for the war was increasingly challenged by strikes and political agitation. In October sailors in the German Imperial Navy mutinied when ordered to set sail for a final confrontation with the British Navy. The Kiel Mutiny sparked off the November Revolution which brought the war to an end. Bethmann Hollweg tried to persuade the Reichstag to opt to negotiate for peace.

Later life

Intellectual supporters of the policy in Berlin, Arnold Wahnschaffe (1865–1941), undersecretary in the chancellery, and Arthur Zimmermann, were his closest and ablest colleagues. Bethmann Hollweg was directly responsible for devising the Flamenpolitik on the Western Front carried out in the Schlieffen Plan, yet this strategy's ultimate failure as a mode of occupation brought economic collapse and military defeat, as was clearly identified by the Bryce Report. The Chancellor's justification lay in the refrain that Germany was fighting a war of national survival.

Bethmann Hollweg received prominent attention throughout the world in June 1919, when he formally asked the Allied and Associated Powers to place him on trial instead of the Kaiser.[15] The Supreme War Council decided to ignore his request. He was often mentioned as among those who might be tried by Allies for political offences in connection with the origin of the war.

In 1919, reports from Geneva said he was rumored in diplomatic circles there as leading the monarchists for both the Hohenzollerns and the Habsburgs, the nucleus of which was said to be located in Switzerland.[3]

The ex-Chancellor spent the short remainder of his life in retirement, writing his memoirs. A little after Christmas 1920, he caught a cold, which developed into acute pneumonia from which he died on 1 January 1921. His wife had died in 1914, and he had lost his eldest son in the war.

He was survived by a daughter, Countess Zech Burkescroda, the wife of the Secretary of the Russian Legation at Munich.[16]

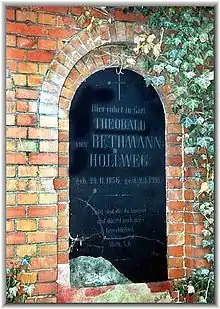

Bethmann Hollweg is buried in Hohenfinow.

Honours and awards

Orders and decorations

.svg.png.webp) Prussia:[17]

Prussia:[17]

- Knight of the Black Eagle, with Collar and in Diamonds

- Knight of the Red Eagle, 3rd Class with Bow and Crown

- Knight of the Crown Order, 2nd Class

- Grand Commander's Cross of the Royal House Order of Hohenzollern

- Red Cross Medal, 3rd Class

- Landwehr Service Medal, 2nd Class

Hohenzollern: Cross of Honour of the Princely House Order of Hohenzollern, 1st Class[17]

Hohenzollern: Cross of Honour of the Princely House Order of Hohenzollern, 1st Class[17] Anhalt: Grand Cross of the Order of Albert the Bear[17]

Anhalt: Grand Cross of the Order of Albert the Bear[17].svg.png.webp) Baden:[17]

Baden:[17]

- Grand Cross of the Zähringer Lion, with Oak Leaves, 1908[18]

- Knight of the House Order of Fidelity

.svg.png.webp) Bavaria:[17]

Bavaria:[17]

- Knight of St. Hubert, 1909[19]

- Grand Cross of Merit of the Bavarian Crown

Brunswick: Grand Cross of the Order of Henry the Lion[17]

Brunswick: Grand Cross of the Order of Henry the Lion[17].svg.png.webp)

.svg.png.webp)

.svg.png.webp) Ernestine duchies: Grand Cross of the Saxe-Ernestine House Order[17]

Ernestine duchies: Grand Cross of the Saxe-Ernestine House Order[17] Grand Duchy of Hesse:[20]

Grand Duchy of Hesse:[20]

- Grand Cross of the Merit Order of Philip the Magnanimous, 21 November 1908

- Grand Cross of the Ludwig Order, 25 November 1910

Mecklenburg:[17]

Mecklenburg:[17]

- Grand Cross of the Wendish Crown, with Golden Crown

- Grand Cross of the Griffon

.svg.png.webp) Saxony:[17]

Saxony:[17]

- Knight of the Rue Crown

- Grand Cross of the Albert Order, with Golden Star

Schaumburg-Lippe: Cross of Honour of the House Order of Schaumburg-Lippe, 1st Class[17]

Schaumburg-Lippe: Cross of Honour of the House Order of Schaumburg-Lippe, 1st Class[17] Württemberg: Grand Cross of the Württemberg Crown[17]

Württemberg: Grand Cross of the Württemberg Crown[17]

.svg.png.webp) Austria-Hungary: Grand Cross of the Royal Hungarian Order of St. Stephen, 1909; in Diamonds, 1917[21]

Austria-Hungary: Grand Cross of the Royal Hungarian Order of St. Stephen, 1909; in Diamonds, 1917[21].svg.png.webp) Belgium: Grand Cordon of the Order of Leopold[17]

Belgium: Grand Cordon of the Order of Leopold[17] Bulgaria: Grand Cross of St. Alexander, with Collar[17]

Bulgaria: Grand Cross of St. Alexander, with Collar[17] Denmark:[22]

Denmark:[22]

- Grand Cross of the Dannebrog, 19 November 1906

- Knight of the Elephant, 25 February 1913

_crowned.svg.png.webp) Italy:[17]

Italy:[17]

- Knight of the Annunciation, 22 March 1910[23]

- Grand Cross of the Crown of Italy

.svg.png.webp) Ottoman Empire: Order of Osmanieh, 1st Class in Diamonds[17]

Ottoman Empire: Order of Osmanieh, 1st Class in Diamonds[17] Persia: Order of the Lion and the Sun, 1st Class in Diamonds[17]

Persia: Order of the Lion and the Sun, 1st Class in Diamonds[17] Romania: Grand Cross of the Crown of Romania[17]

Romania: Grand Cross of the Crown of Romania[17] Russia: Knight of St. Andrew, 1910[17]

Russia: Knight of St. Andrew, 1910[17].svg.png.webp) Spain: Grand Cross of the Order of Charles III, 2 November 1905[24]

Spain: Grand Cross of the Order of Charles III, 2 November 1905[24] Sweden: Commander Grand Cross of the North Star, 1908[25]

Sweden: Commander Grand Cross of the North Star, 1908[25] United Kingdom: Honorary Knight Grand Cross of the Royal Victorian Order[17]

United Kingdom: Honorary Knight Grand Cross of the Royal Victorian Order[17]

Military appointments

- Major general à la suite of the Prussian Army[17]

See also

- Causes of World War I

- German entry into World War I

- History of Germany during World War I

References

- Konrad H. Jarausch, "The Illusion of Limited War: Chancellor Bethmann Hollweg's Calculated Risk, July 1914." Central European History 2.1 (1969): 48-76.

- Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1922). . Encyclopædia Britannica (12th ed.). London & New York: The Encyclopædia Britannica Company.

- Scrap of Paper Chancellor of Germany Dies, The Globe. Toronto, 3 January 1921. accessed on 8 October 2006.

- Keegan, p. 31; Tuchman, p. 59

- Quoted in Keegan, p. 70

- Fischer, 1967, p. 71

- Butler, David Allen (2010). The Burden of Guilt: How Germany Shattered the Last Days of Peace, Summer 1914. Casemate Publishers. p. 103. ISBN 9781935149576. Retrieved 30 July 2012.

- Robson, Stuart (2007). The First World War (1 ed.). Harrow, England: Pearson Longman. p. 25. ISBN 978-1-4058-2471-2 – via Archive Foundation.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: date and year (link) - This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Rines, George Edwin, ed. (1920). . Encyclopedia Americana.

- Tuchman (1970), p. 84

- Isabel V. Hull (2005). Absolute Destruction: Military Culture and the Practices of War in Imperial Germany. Cornell University Press. p. 233. ISBN 0801442583. Retrieved 7 July 2009.

- Foley, Robert T.; Foley, Robert Thomas (6 January 2005). German Strategy and the Path to Verdun: Erich Von Falkenhayn and the Development of Attrition, 1870-1916. Cambridge University Press. p. 115. ISBN 978-0-521-84193-1.

- Robson (2007), p. 68-72

- Wolfgang J. Mommsen,"Public opinion and foreign policy in Wilhelmian Germany, 1897–1914." Central European History 24.4 (1991): 381-401.

- Gary Jonathan Bass Stay the Hand of Vengeance: The Politics of War Crimes Tribunals, Princeton University Press (2002) p. 77

- Jarausch, Konrad (1973). Von Bethmann-Hollweg and the Hubris of Imperial Germany. Yale University Press.

- "Offiziere à la suite der Armee", Rangliste de Königlich Preußischen Armee (in German), Berlin: Ernst Siegfried Mittler & Sohn, 1914, p. 36 – via hathitrust.org

- "Großherzogliche Orden", Hof- und Staats-Handbuch des Großherzogtum Baden, Karlsruhe, 1910, p. 148 – via blb-karlsruhe.de

- "Königliche Orden", Hof- und – Staatshandbuch des Königreichs Bayern (in German), Munich: Druck and Verlag, 1914, p. 11 – via hathitrust.org

- Großherzoglich Hessische Ordensliste (in German), Darmstadt: Staatsverlag, 1914, pp. 9, 21, 99 – via hathitrust.org

- "St. Stephans-Orden", Hof- und Staatshandbuch der Österreichisch-Ungarischen Monarchie, 1918, p. 56, retrieved 15 November 2021

- Bille-Hansen, A. C.; Holck, Harald, eds. (1914) [1st pub.:1801]. Statshaandbog for Kongeriget Danmark for Aaret 1914 [State Manual of the Kingdom of Denmark for the Year 1914] (PDF). Kongelig Dansk Hof- og Statskalender (in Danish). Copenhagen: J.H. Schultz A.-S. Universitetsbogtrykkeri. pp. 5–6, 9–10. Retrieved 16 November 2021 – via da:DIS Danmark.

- Italy. Ministero dell'interno (1920). Calendario generale del regno d'Italia. p. 58.

- "Real y distinguida orden de Carlos III", Guía Oficial de España (in Spanish), Madrid, 1914, p. 210, retrieved 16 November 2021

- Sveriges statskalender (PDF) (in Swedish), 1911, p. 558, retrieved 16 November 2021 – via gupea.ub.gu.se

Further reading

- Bass, Gary Jonathan (2002). Stay the Hand of Vengeance: The Politics of War Crimes Tribunals. Prince, NJ: Princeton University Press.

- Clark, Christopher. Kaiser Wilhelm II: A Life in Power (Penguin UK, 2009).

- Fay, Sidney Bradshaw. The origins of the world war (2 vol 1930), passim; online

- Goerlitz, Walther (1955). History of the German General Staff. New York: Praeger.

- Gooch, G.P. Before the war: studies in diplomacy (2 vol 1936, 1938) online vol 2 pp 201–285.

- Jarausch, Konrad (1973). Von Bethmann-Hollweg and the Hubris of Imperial Germany. Yale University Press.

- Jarausch, Konrad Hugo. "Revising German History: Bethmann-Hollweg Revisited." Central European History 21#3 (1988): 224–243, historiography in JSTOR

- Jarausch, Konrad H. "The Illusion of Limited War: Chancellor Bethmann Hollweg's Calculated Risk, July 1914." Central European History 2.1 (1969): 48-76. online

- Kapp, Richard W. "Bethmann-Hollweg, Austria-Hungary and Mitteleuropa, 1914–1915." Austrian History Yearbook 19.1 (1983): 215-236.

- Langdon, John W. "Emerging from Fischer's shadow: recent examinations of the crisis of July 1914." History Teacher 20.1 (1986): 63–86, historiography in JSTOR

- Sweet, Paul Robinson. "Leaders and Policies: Germany in the Winter 1914-1915" Journal of Central European Affairs (1956) 16#3 pp 229–252.

- Tobias, John L. "The Chancellorship of Bethmann Hollweg and the Question of Leadership of the National Liberal Party." Canadian Journal of History 8.2 (1973): 145-165.

- Watson, Alexander. Ring of Steel: Germany and Austria-Hungary in World War I ( Basic Books, 2014).

Primary sources

- Bethmann-Hollweg, Theobald (1920). Reflections on the World War. London: Butterworths.

- Blucher, Princess Evelyn (1920). An English Wife in Berlin. London: Constable., esp pp 10–24

- Carnegie Endowment for International Peace. Official German Documents Relating to the World War, (2 vol Oxford University Press, 1923), II: 1320–1321. online in English translation

In German

- Wolfgang Gust, ed. (Spring 2005). Der Völkermord an den Armeniern 1915/15: Dokumente aus dem Politischen Archiv des Auswärtigen Amts (The Armenian genocide of 1915: Documents from the political archives of the foreign office), preface by Vahakn N. Dadrian, in German with English abstracts of documents. zu Klampen Verlag. ISBN 3-934920-59-4.

- Janßen, Karl-Heinz: Der Kanzler und der General. Die Führungskrise um Bethmann Hollweg und Falkenhayn. (1914–1916). Musterschmidt, Göttingen u. a. 1967.

- Wollstein, Günter: Theobald von Bethmann Hollweg. Letzter Erbe Bismarcks, erstes Opfer der Dolchstoßlegende (= Persönlichkeit und Geschichte. Bd. 146/147). Muster-Schmidt, Göttingen u. a. 1995, ISBN 3-7881-0145-8.

- Zmarzlik, Hans G.: Bethmann Hollweg als Reichskanzler, 1909–1914. Studien zu Möglichkeiten und Grenzen seiner innerpolitischen Machtstellung (= Beiträge zur Geschichte des Parlamentarismus und der politischen Parteien. Bd. 11, ISSN 0522-6643). Droste, Düsseldorf 1957.

Essays

- Deuerlein, Ernst: Theobald von Bethmann Hollweg. In: Ernst Deuerlein: Deutsche Kanzler. Von Bismarck bis Hitler. List, München 1968, S. 141–173.

- Erdmann, Karl Dietrich: Zur Beurteilung Bethmann Hollwegs (mit Tagebuchauszügen Kurt Riezlers). In: Geschichte in Wissenschaft und Unterricht. Jg. 15, 1964, ISSN 0016-9056, S. 525–540.

- Werner Frauendienst (1955), "Bethmann Hollweg, Theobald Theodor Friedrich Alfred von", Neue Deutsche Biographie (in German), vol. 2, Berlin: Duncker & Humblot, pp. 188–193; (full text online)

- Gutsche, Willibald: Bethmann Hollweg und die Politik der Neuorientierung. Zur innenpolitischen Strategie und Taktik der deutschen Reichsregierung während des ersten Weltkrieges. In: Zeitschrift für Geschichtswissenschaft. Jg. 13, H. 2, 1965, ISSN 0044-2828, S. 209–254.

- Mommsen, Wolfgang J.: Die deutsche öffentliche Meinung und der Zusammenbruch des Regierungssystems Bethmann Hollwegs im Juli 1917. In: Geschichte in Wissenschaft und Unterricht. Jg. 19, 1968, S. 422–440.

- Riezler, Kurt: Nachruf auf Bethmann Hollweg. In: Die deutsche Nation. Jahrgang 3, 1921, ZDB-ID 217417-0.

External links

- Katharine Anne Lerman: "Bethmann Hollweg, Theobald von", in: 1914-1918-online. International Encyclopedia of the First World War.

- Reflections on the World War at the Internet Archive

- Newspaper clippings about Theobald von Bethmann Hollweg in the 20th Century Press Archives of the ZBW

.jpg.webp)