Theodor Herzl

Theodor Herzl[lower-alpha 1] (2 May 1860 – 3 July 1904)[3] was an Austro-Hungarian Jewish lawyer, journalist, playwright, political activist, and writer who was the father of modern political Zionism. Herzl formed the Zionist Organization and promoted Jewish immigration to Palestine in an effort to form a Jewish state.

Theodor Herzl | |

|---|---|

| תֵּאוֹדוֹר הֶרְצְל | |

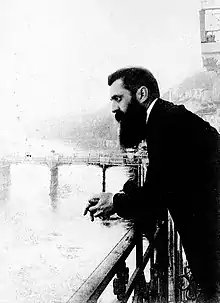

Herzl in 1897 | |

| Born | 2 May 1860 Pest, Kingdom of Hungary, Austrian Empire |

| Died | 3 July 1904 (aged 44) Reichenau an der Rax, Austria-Hungary |

| Resting place | 1904–1949: Döbling Cemetery, Vienna 1949–present: Mt. Herzl, Jerusalem 31°46′26″N 35°10′50″E |

| Other names | Binyamin Ze'ev |

| Citizenship | Hungarian |

| Alma mater | University of Vienna |

| Occupation |

|

| Known for | Father of modern political Zionism |

| Spouse | Julie Naschauer

(m. 1889–1904) |

| Signature | |

Although he died before Israel's establishment, he is known in Hebrew as Chozeh HaMedinah (חוֹזֵה הַמְדִינָה), lit. 'Visionary of the State'.[4] Herzl is specifically mentioned in the Israeli Declaration of Independence and is officially referred to as "the spiritual father of the Jewish State",[5] i.e. the 'visionary' who gave a concrete, practicable platform and framework to political Zionism. However, he was not the first Zionist theoretician or activist; scholars, many of them religious such as rabbis Yehuda Bibas, Zvi Hirsch Kalischer and Judah Alkalai, promoted a range of proto-Zionist ideas before him.[6][7]

Early life

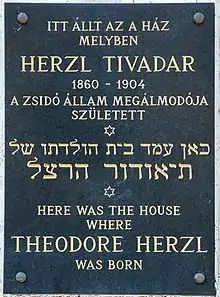

Theodor Herzl was born in the Dohány utca (Tabakgasse in German), a street in the Jewish quarter of Pest (now eastern part of Budapest), Kingdom of Hungary (now Hungary), to a Neolog Jewish family.[3] His father's family had migrated from Zimony (today Zemun, Serbia),[8] to Bohemia in 1739, where they were required to Germanize their family name Loebl (from Hebrew lev, 'heart') to Herzl (diminutive of Ger. Herz; 'little heart').[9]

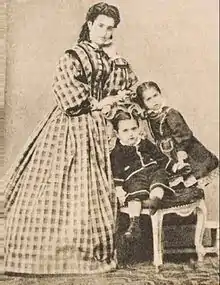

He was the second child of Jeanette and Jakob Herzl, who were German-speaking, assimilated Jews. It is believed Herzl was of both Ashkenazi and Sephardic lineage predominately through his paternal line and to a lesser extent through the maternal line.[10]

Jakob Herzl (1836–1902), Theodor's father, was a highly successful businessman. Herzl had one sister, Pauline, a year older than he was; she died on 7 February 1878, of typhus.[11] Theodor lived with his family in a house next to the Dohány Street Synagogue (formerly known as Tabakgasse Synagogue) located in Belváros, the inner city of the historical old town of Pest, in the eastern section of Budapest.[12][13]

In his youth, Herzl was aspired to follow the footsteps of Ferdinand de Lesseps,[14] builder of the Suez Canal, but did not succeed in the sciences and instead developed a growing enthusiasm for poetry and humanities. This passion later developed into a successful career in journalism and a less-celebrated pursuit of playwrighting.[15] According to Amos Elon,[16] as a young man, Herzl was an ardent Germanophile who saw the Germans as the best Kulturvolk (cultured people) in Central Europe and embraced the German ideal of Bildung, whereby reading great works of literature by Goethe and Shakespeare could allow one to appreciate the beautiful things in life and thus become a morally better person (the Bildung theory tended to equate beauty with goodness).[17] Herzl believed that through Bildung Hungarian Jews such as himself could shake off their "shameful Jewish characteristics" caused by long centuries of impoverishment and oppression, and become civilized Central Europeans, a true Kulturvolk along the German lines.[17]

In 1878, after the death of his sister, Pauline, the family moved to Vienna, Austria-Hungary, and lived in the 9th district, Alsergrund. At the University of Vienna, Herzl studied law. As a young law student, Herzl became a member of the German nationalist Burschenschaft (fraternity) Albia, which had the motto Ehre, Freiheit, Vaterland ("Honor, Freedom, Fatherland").[18] He later resigned in protest at the organisation's antisemitism.[19]

After a brief legal career in the University of Vienna and Salzburg,[20] he devoted himself to journalism and literature, working as a journalist for a Viennese newspaper and a correspondent for Neue Freie Presse, in Paris, occasionally making special trips to London and Istanbul. He later became literary editor of Neue Freie Presse, and wrote several comedies and dramas for the Viennese stage. His early work did not focus on Jewish life. It was of the feuilleton order, descriptive rather than political.[21]

Zionist intellectual and activist

_WITH_MEMBERS_OF_THE_ZION_ORGANIZATION_IN_THE_LUBER_CAFE_IN_VIENNA%252C_1896._%D7%AA%D7%90%D7%95%D7%93%D7%95%D7%A8_%D7%94%D7%A8%D7%A6%D7%9C_%D7%A2%D7%9D_%D7%97%D7%91%D7%A8%D7%99_%D7%90%D7%92%D7%95%D7%93%D7%AA_%D7%A6%D7%99%D7%95%D7%9F_%D7%91%D7%A7%D7%A4%D7%94_%D7%9C%D7%95%D7%91%D7%A8_%D7%91%D7%95%D7%95%D7%99%D7%A0%D7%94._1896.jpg.webp)

As the Paris correspondent for Neue Freie Presse, Herzl followed the Dreyfus affair, a political scandal that divided the Third French Republic from 1894 until its resolution in 1906. It was a notorious antisemitic incident in France in which a Jewish French army captain was falsely convicted of spying for Germany. Herzl was witness to mass rallies in Paris following the Dreyfus trial. There has been some controversy surrounding the impact that this event had on Herzl and his conversion to Zionism. Herzl himself stated that the Dreyfus case turned him into a Zionist and that he was particularly affected by chants of "Death to the Jews!" from the crowds. This had been the widely held belief for some time. However, some modern scholars now believe that due to little mention of the Dreyfus affair in Herzl's earlier accounts and a seemingly contrary reference he made in them to shouts of "Death to the traitor!" that he may have exaggerated the influence it had on him in order to create further support for his goals.[22][23]

Jacques Kornberg claims that the Dreyfus influence was a myth that Herzl did not feel necessary to deflate and that he also believed that Dreyfus was guilty.[24] Another modern claim is that, while upset by antisemitism evident in French society, Herzl, like most contemporary observers, initially believed Dreyfus was guilty and only claimed to have been inspired by the affair years later when it had become an international cause célèbre. Rather, it was the rise to power of the antisemitic demagogue Karl Lueger in Vienna in 1895 that seems to have had a greater effect on Herzl, before the pro-Dreyfus campaign had fully emerged. It was at this time that Herzl wrote his play "The New Ghetto," which shows the ambivalence and lack of real security and equality of emancipated, well-to-do Jews in Vienna. The protagonist is an assimilated Jewish lawyer who tries unsuccessfully to break through the social ghetto enforced on Western Jews.[25]

According to Henry Wickham Steed, Herzl was initially "fanatically devoted to the propagation of Jewish-German 'Liberal' assimilationist doctrine".[26] However, Herzl came to reject his early ideas regarding Jewish emancipation and assimilation and to believe that the Jews must remove themselves from Europe.[27] Herzl grew to believe that antisemitism could not be defeated or cured, only avoided, and that the only way to avoid it was the establishment of a Jewish state.[28] In June 1895, he wrote in his diary: "In Paris, as I have said, I achieved a freer attitude toward anti-semitism ... Above all, I recognized the emptiness and futility of trying to 'combat' anti-semitism." Herzl's editors at Neue Freie Presse refused any publication of his Zionist political activities. A mental clash gripped Herzl, between the craving for literary success and a desire to act as a public figure.[29] Around this time, Herzl started writing pamphlets about A Jewish State. Herzl claimed that these pamphlets resulted in the establishment of the Zionist Movement, and they did play a large role in the movement's rise and success.[30] His testimony before the British Royal Commission reflected his fundamental, romantic liberal view on life as the 'Problem of the Jews'.

Beginning in late 1895, Herzl wrote Der Judenstaat (The State of the Jews), which was published February 1896 to immediate acclaim and controversy. The book argued that the Jewish people should leave Europe for Palestine, their historic homeland. The Jews possessed a nationality; all they were missing was a nation and a state of their own.[31] Only through a Jewish state could they avoid antisemitism, express their culture freely and practice their religion without hindrance.[31] Herzl's ideas spread rapidly throughout the Jewish world and attracted international attention.[32] Supporters of existing Zionist movements, such as the Hovevei Zion, immediately allied themselves with him, but he also encountered bitter opposition from members of the Orthodox community and those seeking to integrate in non-Jewish society.[33]

Vision of a Jewish homeland

In Der Judenstaat he writes:

"The Jewish question persists wherever Jews live in appreciable numbers. Wherever it does not exist, it is brought in together with Jewish immigrants. We are naturally drawn into those places where we are not persecuted, and our appearance there gives rise to persecution. This is the case, and will inevitably be so, everywhere, even in highly civilised countries—see, for instance, France—so long as the Jewish question is not solved on the political level."[34]

The book concludes:

Therefore I believe that a wondrous generation of Jews will spring into existence. The Maccabeans will rise again. Let me repeat once more my opening words: The Jews who wish for a State will have it. We shall live at last as free men on our own soil, and die peacefully in our own homes. The world will be freed by our liberty, enriched by our wealth, magnified by our greatness. And whatever we attempt there to accomplish for our own welfare, will react powerfully and beneficially for the good of humanity.[35]

Diplomatic liaison with the Ottomans

Herzl began to energetically promote his ideas, continually attracting supporters, Jewish and non-Jewish. According to Norman Rose, Herzl "mapped out for himself the role of martyr ... as the Parnell of the Jews".[36] Herzl saw an opportunity in the mid-1890s anti-Armenian Hamidian massacres which severely tarnished the public image of the sultan in Europe. He proposed that in exchange for Jewish settlement in Palestine, the Zionist movement could work to improve Abdul Hamid II's reputation and shore up the empire's finances. Bernard Lazare harshly criticized this position, arguing that Herzl and other delegates of the Zionist Congress "have sent their blessing to the worst of murderers".[37]

On 10 March 1896, Herzl was visited by Reverend William Hechler, the Anglican minister to the British Embassy in Vienna. Hechler had read Herzl's Der Judenstaat, and the meeting became central to the eventual legitimization of Herzl and Zionism.[38] Herzl later wrote in his diary, "Next we came to the heart of the business. I said to him: (Theodor Herzl to Rev. William Hechler) I must put myself into direct and publicly known relations with a responsible or non responsible ruler – that is, with a minister of state or a prince. Then the Jews will believe in me and follow me. The most suitable personage would be the German Kaiser."[39] Hechler arranged an extended audience with Frederick I, Grand Duke of Baden, in April 1896. The Grand Duke was the uncle of the German Emperor Wilhelm II. Through the efforts of Hechler and the Grand Duke, Herzl publicly met Wilhelm II in 1898. The meeting significantly advanced Herzl's and Zionism's legitimacy in Jewish and world opinion.[40]

In May 1896, the English translation of Der Judenstaat appeared in London as The Jewish State. Herzl had earlier confessed to his friend Max Bodenheimer that he "wrote what I had to say without knowing my predecessors, and it can be assumed that I would not have written it [Der Judenstaat] had I been familiar with the literature".[41]

In Istanbul, Ottoman Empire, 15 June 1896, Herzl saw an opportunity. With the assistance of Count Philip Michael von Nevlinski, a Polish émigré with political contacts in the Ottoman Court, Herzl attempted to meet Sultan Abdulhamid II in order to present his solution of a Jewish State to the Sultan directly.[42] He failed to obtain an audience but did succeed in visiting a number of highly placed individuals, including the Grand Vizier, who received him as a journalist representing the Neue Freie Presse. Herzl presented his proposal to the Grand Vizier: the Jews would pay the Turkish foreign debt and help Turkey regain its financial footing in return for Palestine as a Jewish homeland. Prior to leaving Istanbul, 29 June 1896, Herzl was granted a symbolic medal of honor.[43] The medal, the "Commander's Cross of the Order of the Medjidie," was a public relations affirmation for Herzl and the Jewish world of the seriousness of the negotiations.

Five years later, 17 May 1901, Herzl met with Sultan Abdulhamid II,[44] who turned down Herzl's offer to consolidate the Ottoman debt in exchange for a charter allowing the Zionists access to Palestine.[45]

Returning from Istanbul, Herzl traveled to London to report back to the Maccabeans, a proto-Zionist group of established English Jews led by Colonel Albert Goldsmid. In November 1895 they received him with curiosity, indifference and coldness. Israel Zangwill bitterly opposed Herzl, but after Istanbul, Goldsmid agreed to support Herzl. In London's East End, a community of primarily Yiddish speaking recent Eastern European Jewish immigrants, Herzl addressed a mass rally of thousands on 12 July 1896 and was received with acclaim. They granted Herzl the mandate of leadership for Zionism. Within six months this mandate had been expanded throughout Zionist Jewry: the Zionist movement grew rapidly.

World Jewish Congress

In 1897, at considerable personal expense, he founded the Zionist newspaper Die Welt in Vienna, Austria-Hungary, and planned the First Zionist Congress in Basel, Switzerland. He was elected president of the Congress (a position he held until his death in 1904), and in 1898 he began a series of diplomatic initiatives to build support for a Jewish country. He was received by Wilhelm II on several occasions, one of them in Jerusalem, and attended the Hague Peace Conference, enjoying a warm reception from many statesmen there.

His work on Autoemancipation was pre-figured by a similar conclusion drawn by Marx's friend Moses Hess, in Rome and Jerusalem (1862). Pinsker had never yet read it, but was aware of the distant and far off Hibbat Zion. Herzl's philosophical instruction highlighted the weaknesses and vulnerabilities. To Herzl each dictator or leader had a nationalistic identity, even down to the Irish from Wolfe Tone onwards. He was drawn to the mawkishness of Judaism rendered distinctively as German. But he remained convinced that Germany was the centre (Hauptsitz) of antisemitism rather than France. In a much quoted aside he noted "If there is one thing I should like to be, it is a member of old Prussian nobility".[46] Herzl appealed to the nobility of Jewish England – the Rothschilds, Sir Samuel Montagu, later cabinet minister, to the Chief Rabbis of France and Vienna, the railroad magnate, Baron Hirsch.

He fared best with Israel Zangwill, and Max Nordau. They were both well-known writers or 'men of letters'—imagination that engenders understanding. Hirsch's correspondence led nowhere. Baron Albert Rothschild had little to do with the Jews.[47] Herzl was disliked by the bankers (Finanzjuden) and detested them. Herzl was defiant of their social authority. He also shared Pinkser's pessimistic opinion that the Jews had no future in Europe; that they were too antisemitic to tolerate because each country in Europe had tried antisemitic assimilation. In Berlin they said Juden raus in a well worn phrase. Herzl therefore advocated a mass exodus from Europe to the Judenstaat. Pinkser's manifesto was a cry for help; a warning to others Mahnruf, a call for attention to their plight. Herzl's vision was less about mental states of Jewry, and more about delivering prescriptive answers about land. "The idea that i have developed is a very old one; it is the restoration of the Jewish State"[48] was a follow-up of Pinkser's early weaker version Mahnruf an seine Stammesgenossen von einem nassichen Juden.[49]

Zionism and the Holy Land

Herzl visited Jerusalem for the first time in October 1898.[50] He deliberately coordinated his visit with that of Wilhelm II to secure what he thought had been prearranged with the aid of Rev. William Hechler, public world power recognition of himself and Zionism.[51] Herzl and Wilhelm II first met publicly on 29 October, at Mikveh Israel, near present-day Holon, Israel. It was a brief but historic meeting.[38] He had a second formal, public audience with the emperor at the latter's tent camp on Street of the Prophets in Jerusalem on 2 November 1898.[40][52][53] The English Zionist Federation, the local branch of the World Zionist Organization was founded in 1899, that Herzl had established in Austria in 1897.[54]

In 1902–03, Herzl was invited to give evidence before the British Royal Commission on Alien Immigration. His appearance brought him into close contact with members of the British government, particularly with Colonial Secretary Joseph Chamberlain through whom he negotiated with the Egyptian government for a charter for the settlement of the Jews in Al 'Arish in the Sinai Peninsula, adjoining southern Palestine. The project was blocked as impractical by Lord Cromer, the Consul General in Egypt.

In 1903, Herzl attempted to obtain support for the Jewish homeland from Pope Pius X, an idea broached at 6th Zionist Congress. Palestine could offer a safe refuge for those fleeing persecution in Russia.[55] Cardinal Rafael Merry del Val ordained that the Church's policy was explained non-possumus on such matters, decreeing that as long as the Jews denied the divinity of Christ, the Catholics could not make a declaration in their favour.[56]

In 1903, following Kishinev pogrom, Herzl visited St. Petersburg and was received by Sergei Witte, then finance minister, and Viacheslav Plehve, minister of the interior, the latter placing on record the attitude of his government toward the Zionist movement. On that occasion Herzl submitted proposals for the amelioration of the Jewish position in Russia.

At the same time Joseph Chamberlain floated the idea of a Jewish Colony in what is now Kenya. The plan became known as the "Uganda Project" and Herzl presented it to the Sixth Zionist Congress (Basel, August 1903), where a majority (295:178, 98 abstentions) agreed to investigating this offer. The proposal faced strong opposition particularly from the Russian delegation who stormed out of the meeting.[57] In 1905 the 7th Zionist Congress, after investigations, decided to decline the British offer and firmly committed itself to a Jewish homeland in Palestine.[58] A Heimstatte—a homeland for the Jewish people in Palestine secured by public law.[59]

Death and burial

Herzl did not live to see the rejection of the Uganda plan. At 5 p.m. 3 July 1904, in Edlach, a village inside Reichenau an der Rax, Lower Austria, Theodor Herzl, having been diagnosed with a heart issue earlier in the year, died of cardiac sclerosis. A day before his death, he told the Reverend William H. Hechler: "Greet Palestine for me. I gave my heart's blood for my people."[60]

His will stipulated that he should have the poorest-class funeral without speeches or flowers and he added, "I wish to be buried in the vault beside my father, and to lie there till the Jewish people shall take my remains to Israel".[61] Nevertheless, some six thousand followed Herzl's hearse, and the funeral was long and chaotic. Despite Herzl's request that no speeches be made, a brief eulogy was delivered by David Wolffsohn. Hans Herzl, then thirteen, read the kaddish.[62]

First buried at the Viennese cemetery in the district of Döbling,[63] his remains were brought to Israel in 1949 and buried on Mount Herzl in Jerusalem, which was named after him. The coffin was draped in a blue and white pall decorated with a Star of David circumscribing a Lion of Judah and seven gold stars recalling Herzl's original proposal for a flag of the Jewish state.[64]

Legacy and commemoration

Herzl Day (Hebrew: יום הרצל) is an Israeli national holiday celebrated annually on the tenth of the Hebrew month of Iyar, to commemorate the life and vision of Zionist leader Theodor Herzl.[65]

Family

Herzl's grandfathers, both of whom he knew, were more closely related to traditional Judaism than were his parents. In Zimony (Zemlin), his grandfather Simon Loeb Herzl "had his hands on" one of the first copies of Judah Alkalai's 1857 work prescribing the "return of the Jews to the Holy Land and renewed glory of Jerusalem". Contemporary scholars conclude that Herzl's own implementation of modern Zionism was undoubtedly influenced by that relationship. Herzl's grandparents' graves in Semlin can still be visited. Alkalai himself witnessed the rebirth of Serbia from Ottoman rule in the early and mid-19th century and was inspired by the Serbian uprising and subsequent re-creation of Serbia.

On 25 June 1889, he married Julie Naschauer, the 21-year-old daughter of a wealthy Jewish businessman in Vienna.[66] The marriage was unhappy, although three children were born to it: Paulina, Hans and Margaritha (Trude). One of his biographers [67] suggests that Herzl infected his wife with Gonorrhea which he contracted in 1880.[68] Herzl had a strong attachment to his mother, who was unable to get along with his wife. These difficulties were increased by the political activities of his later years, in which his wife took little interest. Julie died in 1907, 3 years after Herzl, aged 39.[69] His wife is the protagonist in the fictitious historical novel, His Alienated Wife, written by Eda Zoritte and published by Keter Publishing House in 1997.[70]

His daughter Paulina suffered from mental illness and drug addiction. She died in 1930 at the age of 40 of a heroin overdose.[71]

His only son Hans was given a secular upbringing and Herzl notably refused to allow him to be circumcised.[72][73][74] After Herzl's early death, Hans successively converted[75] and became a Baptist, then a Catholic, and flirted with other Protestant denominations. He sought a personal salvation for his own religious needs and a universal solution, as had his father, to Jewish suffering caused by antisemitism. Hanz Herzl voluntarily had himself circumcised 29 May 1905;[76] Hans shot himself to death on the day of his sister Paulina's funeral; he was 39 years old.[77]

Hans left a suicide note explaining his reasons.

"A Jew remains a Jew, no matter how eagerly he may submit himself to the disciplines of his new religion, how humbly he may place the redeeming cross upon his shoulders for the sake of his former coreligionists, to save them from eternal damnation: a Jew remains a Jew ... I can't go on living. I have lost all trust in God. All my life I've tried to strive for the truth, and must admit today at the end of the road that there is nothing but disappointment. Tonight I have said Kaddish for my parents—and for myself, the last descendant of the family. There is nobody who will say Kaddish for me, who went out to find peace—and who may find peace soon ... My instinct has latterly gone all wrong, and I have made one of those irreparable mistakes, which stamp a whole life with failure. Then it is best to scrap it."[78][79]

In 2006 the remains of Paulina and Hans were moved from Bordeaux, France, and reburied not far from their father on Mt. Herzl.[77][80][81]

Paulina and Hans had little contact with their young sister, "Trude" (Margarethe, 1893–1943). She married Richard Neumann, a man 17 years her elder. Neumann lost his fortune in the Great Depression. Burdened by the steep costs of hospitalizing Trude, who suffered from severe bouts of depressive illness that required repeated hospitalization, the Neumanns' financial life was precarious. The Nazis sent Trude and Richard to the Theresienstadt concentration camp where they died. Her body was burned.[77] (Her mother, who died in 1907, was cremated. Her ashes were lost by accident.)

At the request of his father Richard Neumann, Trude's son (Herzl's only grandchild), Stephan Theodor Neumann, (1918–1946) was sent for his safety to England in 1935 to the Viennese Zionists and the Zionist Executive in Israel based there .[82] The Neumanns deeply feared for the safety of their only child as violent Austrian antisemitism expanded. In England he read extensively about his grandfather. Zionism had not been a significant part of his background in Austria, but Stephan became an ardent Zionist, was the only descendant of Theodor Herzl to have become one. Anglicizing his name to Stephen Norman, during World War II, Norman enlisted in the British Army rising to the rank of Captain in the Royal Artillery. In late 1945 and early 1946 he took the opportunity to visit the British Mandate of Palestine "to see what my grandfather had started." He wrote in his diary extensively about his trip. What most impressed him was the "look of freedom" on the faces of the children, which were not like the sallow look of those from the concentration camps of Europe. He wrote upon leaving Israel, "My visit to Israel is over ... It is said that to go away is to die a little. And I know that when I went away from Erez Israel, I died a little. But sure, then, to return is somehow to be reborn. And I will return."[83]

Norman planned to return to Israel following his military discharge. The Zionist Executive had worked for years through Dr. L. Lauterbach to get Norman to come to Israel as a symbol of Herzl's returning.[84]

Operation Agatha of 29 June 1946, precluded that possibility: local military and police fanned out throughout the Mandate and arrested Jewish activists. About 2,700 individuals were arrested. On 2 July 1946, Norman wrote to Mrs.Stybovitz-Kahn in Haifa. Her father, Jacob Kahn, had been a good friend of Herzl and a well-known Dutch banker before the war. Norman wrote, "I intend to go to Israel on a long visit in the future, in fact as soon as passport & permit regulations permit. But the dreadful news of the last two days have done nothing to make this easier."[85] He never did return to Israel.

Discharged from the army in late spring 1946, without money or job and despondent about his future, Norman followed the advice of Dr.Selig Brodetsky. Dr. H. Rosenblum, the editor of Haboker, a Tel Aviv daily that later became Yediot Aharonot, noted in late 1945 that Dr. Weizmann deeply resented the sudden intrusion and reception of Norman when he arrived in Britain. Norman spoke to the Zionist conference in London. Haboker reported, "Something similar happened at the Zionist conference in London. The chairman suddenly announced to the meeting that in the hall there was Herzl's grandson who wanted to say a few words. The introduction was made in an absolutely dry and official way. It was felt that the chairman looked for—and found—some stylistic formula which would satisfy the visitor without appearing too cordial to anybody among the audience. In spite of that there was a great thrill in the hall when Norman mounted on the platform of the praesidium. At that moment, Dr.Weizmann turned his back on the speaker and remained in this bodily and mental attitude until the guest had finished his speech."[86] The 1945 article went on to note that Norman was snubbed by Weizmann and by some in Israel during his visit because of ego, jealousy, vanity and their own personal ambitions. Brodetsky was Chaim Weizman's principal ally and supporter in Britain.

Chaim Weizmann secured for Norman a desirable but minor position with the British Economic and Scientific Mission in Washington, D.C. In late August 1946, shortly after arriving in Washington, he learned that his family had perished. Norman had re-established contact with his old nanny in Vienna, Wuth, who told him what happened.[87] Norman became deeply depressed over the fate of his family and his inability to help the Jewish people "languishing" in the European camps. Unable to endure his suffering any further, he jumped to his death from the Massachusetts Avenue Bridge in Washington, D.C. on 26 November 1946.

Norman was buried by the Jewish Agency in Washington, D.C. His tombstone read simply, 'Stephen Theodore Norman, Captain Royal Artillery British Army, Grandson of Theodor Herzl, 21 April 1918 − 26 November 1946'.[88] Norman was the only descendant of Herzl to have been a Zionist, been to Israel and openly stated his desire to return.

On 5 December 2007, sixty-one years after his death, he was reburied with his family on Mt. Herzl, in the Plot for Zionist Leaders.[89][90][91][92][93]

The Stephen Norman garden on Mount Herzl in Jerusalem—the only memorial in the world to a Herzl other than Theodor Herzl—was dedicated on 2 May 2012 by the Jerusalem Foundation and the Jewish American Society for Historic Preservation.[94]

Writings

Beginning in late 1895, Herzl wrote Der Judenstaat (The State of the Jews). The small book was initially published 14 February 1896, in Leipzig, Germany, and Vienna, Austria, by M. Breitenstein's Verlags-Buchhandlung. It is subtitled "Versuch einer modernen Lösung der Judenfrage", ("Proposal of a modern solution for the Jewish question"). Der Judenstaat proposed the structure and beliefs of what political Zionism was.[95]

Herzl's solution was the creation of a Jewish state. In the book he outlined his reasoning for the need to reestablish the historic Jewish state.

"The idea I have developed in this pamphlet is an ancient one: It is the restoration of the Jewish State ..."

"The decisive factor is our propelling force. And what is that force? The plight of the Jews ... I am profoundly convinced that I am right, though I doubt whether I shall live to see myself proved so. Those who today inaugurate this movement are unlikely to live to see its glorious culmination. But the very inauguration is enough to inspire in them a high pride and the joy of an inner liberation of their existence ..."

"The plan would seem mad enough if a single individual were to undertake it; but if many Jews simultaneously agree on it, it is entirely reasonable, and its achievement presents no difficulties worth mentioning. The idea depends only on the number of its adherents. Perhaps our ambitious young men, to whom every road of advancement is now closed, and for whom the Jewish state throws open a bright prospect of freedom, happiness, and honor, perhaps they will see to it that this idea is spread ..."

"It depends on the Jews themselves whether this political document remains for the present a political romance. If this generation is too dull to understand it rightly, a future, finer, more advanced generation will arise to comprehend it. The Jews who will try it shall achieve their State; and they will deserve it ..."

"I consider the Jewish question neither a social nor a religious one, even though it sometimes takes these and other forms. It is a national question, and to solve it we must first of all establish it as an international political problem to be discussed and settled by the civilized nations of the world in council.

"We are a people—one people.

"We have sincerely tried everywhere to merge with the national communities in which we live, seeking only to preserve the faith of our fathers. It is not permitted us. In vain are we loyal patriots, sometimes superloyal; in vain do we make the same sacrifices of life and property as our fellow citizens; in vain do we strive to enhance the fame of our native lands in the arts and sciences, or her wealth by trade and commerce. In our native lands where we have lived for centuries we are still decried as aliens, often by men whose ancestors had not yet come at a time when Jewish sighs had long been heard in the country ..."

"Oppression and persecution cannot exterminate us. No nation on earth has endured such struggles and sufferings as we have. Jew-baiting has merely winnowed out our weaklings; the strong among us defiantly return to their own whenever persecution breaks out ..."

"Wherever we remain politically secure for any length of time, we assimilate. I think this is not praiseworthy ..."

"Israel is our unforgettable historic homeland ..."

"Let me repeat once more my opening words: The Jews who will it shall achieve their State. We shall live at last as free men on our own soil, and in our own homes peacefully die. The world will be liberated by our freedom, enriched by our wealth, magnified by our greatness. And whatever we attempt there for our own benefit will redound mightily and beneficially to the good of all mankind."[96]

His last literary work, Altneuland (in English: The Old New Land, 1902), is a novel devoted to Zionism. Herzl occupied his free time for three years in writing what he believed might be accomplished by 1923. Though the form is that of a romance, it is less a novel than a serious forecast of what could be done within one generation. The keynotes of the story are love of Zion and insistence upon the fact that the suggested changes in life are not utopian but to be brought about simply by grouping all the best efforts and ideals of every race and nation. Each such effort is quoted and referred to in such a manner as to show that Altneuland, though blossoming through the skill of the Jew, will in reality be the product of the benevolent efforts of all the members of the human family.

Herzl envisioned a Jewish state that combined modern Jewish culture with the best of the European heritage. Thus a "Palace of Peace" would be built in Jerusalem to arbitrate international disputes, and at the same time the Temple would be rebuilt on modern principles. Herzl did not envision the Jewish inhabitants of the state as being religious, but there was respect for religion in the public sphere. He also assumed that many languages would be spoken, and that Hebrew would not be the main tongue. Proponents of a Jewish cultural rebirth, such as Ahad Ha'am, were critical of Altneuland.

In Altneuland, Herzl did not foresee any conflict between Jews and Arabs. One of the main characters in Altneuland is a Haifa engineer, Reshid Bey, who is one of the leaders of the "New Society". He is very grateful to his Jewish neighbors for improving the economic condition of Israel and sees no cause for conflict. All non-Jews have equal rights, and an attempt by a fanatical rabbi to disenfranchise the non-Jewish citizens of their rights fails in the election which is the center of the main political plot of the novel.[97]

Herzl also envisioned the future Jewish state to be a "third way" between capitalism and socialism, with a developed welfare program and public ownership of the main natural resources. Industry, agriculture and trade were organized on a cooperative basis. Along with many other progressive Jews of the day, such as Emma Lazarus, Louis Brandeis, Albert Einstein, and Franz Oppenheimer, Herzl desired to enact the land reforms proposed by the American political economist Henry George. Specifically, they called for a land value tax.[98] He called his mixed economic model "Mutualism", a term derived from French utopian socialist thinking. Women would have equal voting rights—as they had in the Zionist movement from the Second Zionist Congress onwards.

In Altneuland, Herzl outlined his vision for a new Jewish state in the Land of Israel. He summed up his vision of an open society:

"It is founded on the ideas which are a common product of all civilized nations ... It would be immoral if we would exclude anyone, whatever his origin, his descent, or his religion, from participating in our achievements. For we stand on the shoulders of other civilized peoples ... What we own we owe to the preparatory work of other peoples. Therefore, we have to repay our debt. There is only one way to do it, the highest tolerance. Our motto must therefore be, now and ever: 'Man, you are my brother.'"[99]

"If you will it, it is no dream." a phrase from Herzl's book Old New Land, became a popular slogan of the Zionist movement—the striving for a Jewish National Home in Israel.[100]

In his novel, Herzl wrote about an electoral campaign in the new state. He directed his wrath against the nationalist party, which wished to make the Jews a privileged class in Israel. Herzl regarded that as a betrayal of Zion, for Zion was identical to him with humanitarianism and tolerance—and that this was true in politics as well as religion. Herzl wrote:

"Matters of faith were once and for all excluded from public influence ... Whether anyone sought religious devotion in the synagogue, in the church, in the mosque, in the art museum, or in a philharmonic concert, did not concern society. That was his [own] private affair."[99]

Altneuland was written both for Jews and non-Jews: Herzl wanted to win over non-Jewish opinion for Zionism.[101] When he was still thinking of Argentina as a possible venue for massive Jewish immigration, he wrote in his diary:

"When we occupy the land, we shall bring immediate benefits to the state that receives us. We must expropriate gently the private property on the estates assigned to us. We shall try to spirit the penniless population across the border by procuring employment for it in the transit countries, while denying it any employment in our country. The property owners will come over to our side. Both the process of expropriation and the removal of the poor must be carried out discretely and circumspectly ... It goes without saying that we shall respectfully tolerate persons of other faiths and protect their property, their honor, and their freedom with the harshest means of coercion. This is another area in which we shall set the entire world a wonderful example ... Should there be many such immovable owners in individual areas [who would not sell their property to us], we shall simply leave them there and develop our commerce in the direction of other areas which belong to us",[102]

Herzl's draft of a charter for a Jewish-Ottoman Land Company (JOLC) gave the JOLC the right to obtain land in Israel by giving its owners comparable land elsewhere in the Ottoman empire.

The name "Tel Aviv" was the title given to the Hebrew translation of Altneuland by the translator, Nahum Sokolow. This name comes from Ezekiel 3:15 and means tell—an ancient mound formed when a town is built on its own debris for thousands of years—of spring. The name was later applied to the new town built outside Jaffa that became Tel Aviv-Yafo, the second-largest city in Israel. The nearby city to the north, Herzliya, was named in honour of Herzl.

Published works

Books

- The Jewish State (Der Judenstaat), (1896) full text online

- The Old New Land (Altneuland), (1902)

- Hagenau (1881)[103]

Plays

- Kompagniearbeit, comedy in one act, Vienna 1880

- Die Causa Hirschkorn, comedy in one act, Vienna 1882

- Tabarin, comedy in one act, Vienna 1884

- Muttersöhnchen, in four acts, Vienna 1885 (Later: "Austoben" by H. Jungmann)

- Seine Hoheit, comedy in three acts, Vienna 1885

- Der Flüchtling, comedy in one act, Vienna 1887

- Wilddiebe, comedy in four acts, in co-authorship with H. Wittmann, Vienna 1888

- Was wird man sagen?, comedy in four acts, Vienna 1890

- Die Dame in Schwarz, comedy in four acts, in co-authorship with H. Wittmann, Vienna 1890

- Prinzen aus Genieland, comedy in four acts, Vienna 1891

- Die Glosse, comedy in one act, Vienna 1895

- Das Neue Ghetto, drama in four acts, Vienna 1898. Herzl's only play with Jewish characters.[105] Translated as The New Ghetto by Heinz Norden, New York 1955

- Unser Kätchen, comedy in four acts, Vienna 1899

- Gretel, comedy in four acts, Vienna 1899

- I love you, comedy in one act, Vienna 1900

- Solon in Lydien, drama in three acts, Vienna 1905

Other

- Herzl, Theodor. Theodor Herzl: Excerpts from His Diaries (2006) excerpt and text search

- Herzl, Theodor. Philosophische Erzählungen Philosophical Stories (1900), ed. by Carsten Schmidt. new edition Lexikus Publ. 2011, ISBN 978-3-940206-29-9.

- Herzl, Theodor (1922): Theodor Herzls tagebücher, 1895–1904, Volume: 1

- Herzl, Theodor (1922): Theodor Herzls tagebücher, 1895–1904, Volume: 2

See also

- Gathering of Israel

- Herzl Day

- Jewish diaspora

- Return to Zion

Notes

- /ˈhɜːrtsəl, ˈhɛərtsəl/ HURT-səl, HAIRT-səl,[1] German: [ˈhɛʁtsl̩]; Hebrew: תֵּאוֹדוֹר הֶרְצְל, romanized: Te'odor Hertzel; Hungarian: Herzl Tivadar; Hebrew name given at his brit milah: Binyamin Ze'ev[2]

References

- "Herzl". Dictionary.com Unabridged (Online). n.d. Retrieved 17 October 2018.

- Esor Ben-Sorek (18 October 2015). "The Tragic Herzl Family History". Times of Israel.

At his brit mila he was given the Hebrew name Binyamin Zeev

- Cohen, Israel (1959). Theodor Herzl, founder of political Zionism. T. Yoseloff. p. 19.

- "מילון מורפיקס | חוזה המדינה באנגלית | פירוש חוזה המדינה בעברית". www.morfix.co.il (in Hebrew). Retrieved 17 August 2022.

- Israel Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Declaration of Establishment of State of Israel

- "Lehman-Wilzig, Sam N. "Proto-Zionism and its Proto-Herzl: The Philosophy and Efforts of Rabbi Zvi Hirsch Kalischer." Tradition: A Journal of Orthodox Jewish Thought 16.1 (1976): 56–76" (PDF). profslw.com. Retrieved 17 August 2022.

- Penkower, Monty N. "Religious Forerunners of Zionism." Judaism 33.3 (1984): 289.

- Theodor's father and grandfather were born in Zemun. See Loker, Zvi (2007). "Zemun". In Berenbaum, Michael; Skolnik, Fred (eds.). Encyclopedia Judaica. Vol. 1 (2nd ed.). Detroit: Macmillan Reference. pp. 507–508. Retrieved 1 November 2013.

- Kornberg, Jacques (22 November 1993). Theodor Herzl: From Assimilation to Zionism. Indiana University Press. ISBN 0253112591. Retrieved 17 August 2022 – via Google Books.

- Peres 1999, p. 123.

- "Theodor Herzl – Background". About Israel. Archived from the original on 3 August 2016. Retrieved 26 October 2011.

- Herzl, Theodor (14 January 1898). "An Autobiography". The Jewish Chronicle. No. 1. p. 20. Retrieved 1 April 2017.

I was born in 1860 in Budapest in a house next to the synagogue where lately the rabbi denounced me from the pulpit in very sharp terms (...)

- Herzl, Theodor (1960). "Herzl Speaks: His Mind on Issues, Events and Men". Herzl Institute Pamphlet. 16. Archived from the original on 19 November 2005.

I went ... to the synagogue [in Paris] and found the services once again solemn and moving. Much reminded me of my youth and the Tabakgasse synagogue in Pest.

- Chouraqui, André. A Man Alone: The Life of Theodor Herzl. Keter Books, 1970, p. 11.

- Elon, Amos (1975). Herzl, pp. 21–22, New York: Holt, Rinehart and Winston. ISBN 978-0-03-013126-4.

- Elon, Amos (1975). Herzl, p. 23, New York: Holt, Rinehart and Winston. ISBN 978-0-03-013126-4

- Buruma, Ian Anglomania: A European Love Affair, New York: Vintage Books, 1998, p. 180.

- Helge Dvorak (1999). "Herzl, Theodor". Biographisches Lexikon der Deutschen Burschenschaft (in German). Vol. Band I: Politiker Teil 2:F-H. Heidelberg: Universitätsverlag C. Winter. pp. 317–318. ISBN 3-8253-0809-X.

- "Herzl A Man of His Times". herzl.org. Archived from the original on 8 September 2013. Retrieved 17 August 2022.

- "Theodor Herzl (1860–1904)". Jewish Agency for Israel. Archived from the original on 30 September 2009. Retrieved 8 August 2009.

He received a doctorate in law in 1884 and worked for a short while in courts in Vienna and Salzburg.

- M. Reich-Ranicki, Mein Leben, (München 2001, DTV GmbH & C0. – ISBN 3-423-12830-5), p. 64.

- Cohn, Henry J., "Theodor Herzl's Conversion to Zionism," Jewish Social Studies, Vol. 32, No. 2 (Apr. 1970), pp. 101–110, Indiana University Press, https://www.jstor.org/stable/4466575

- Hoare, Liam, "Did Dreyfus Affair Really Inspire Herzl?" The Forward, 26 February 2014.

- Jacques Kornberg, "Theodor Herzl: A Reevaluation". Journal of Modern History, Vol. 52, No. 2 (Jun. 1980), pp. 226–252 Published by the University of Chicago Press

- "Das neue Ghetto". Archived from the original on 8 August 2018. Retrieved 1 February 2018.

- The Habsburg Monarchy (London 1914), p. 188

- Rubenstein, Richard L., and Roth, John K. (2003). Approaches to Auschwitz: The Holocaust and Its Legacy, p. 94. Louisville. Kentucky: Westminster John Knox Press. ISBN 0-664-22353-2.

- Kornberg, Jacques (1 December 1993). Theodor Herzl: From Assimilation to Zionism. Jewish Literature and Culture. Bloomington, Indiana: Indiana University Press. pp. 193–194. ISBN 978-0-253-33203-5. Retrieved 8 August 2009.

"Thus, for the time being, antisemitism is alien to the French people, and they are unable to comprehend it ...

By contrast, several months later ... Herzl was to offer a far different assessment of antisemitism in Austria, as a power and mainline movement on an upward course. Moreover, his fury over Austrian antisemitism had no parallel in his reaction to French antisemitism. - Vital, A People Apart, vol. 2, p. 439

- Royal Commission on Alien Immigration, 'Minutes of Evidence', 7 July 1902, p. 211

- Cleveland, William L. A History of the Modern Middle East. Boulder, CO: Westview, 2004. Print. p. 224

- Chief Rabbi of Vienna, Moritz Gudemann, "Since the Destruction of the Second Temple, the Jews have ceased to be a political-national identity", from Gudemann, National Judentum, (1897); M Graens, 'Jewry in Modern Period', in eds., Frankell & Zipperstein, p. 162

- "Herzl and the rabbis", Haaretz

- Herzl, Der Judenstaat, cited by C.D. Smith, Israel and the Arab-Israeli Conflict, 2001, 4th ed., p. 53

- The Project Gutenberg eBook of The Jewish State, by Theodor Herzl. gutenberg.org. 2 May 2008.

- Norman Rose, A Senseless, Squalid War: Voices from Israel, 1945–1948, The Bodley Head, London, 2009, p. 2)

- Auron, Yair (2001). "Zionist and Israeli Attitudes Toward the Armenian Genocide". In Bartov, Omer; Mack, Phyllis (eds.). In God's Name: Genocide and Religion in the Twentieth Century. Berghahn Books. pp. 268–269. ISBN 978-1-57181-302-2.

- Jerry Klinger (July 2010). "Reverend William H. Hechler—The Christian minister who legitimized Theodor Herzl". Jewish Magazine. Archived from the original on 18 April 2014. Retrieved 26 October 2011.

- The Diaries of Theodor Herzl, edited by Marvin Lowenthal, Gloucester, Massachusetts, Peter Smith Pub., 1978 p. 105

- London Daily Mail Friday 18 November 1898 "An Eastern Surprise: Important Result of the Kaiser's Tour: Sultan and Emperor Agreed in Palestine: Benevolent Sanction Given to the Zionist Movement One of the most important results, if not the most important, of the Kaiser's visit to Palestine is the immense impetus it has given to Zionism, the movement for the return of the Jews to Palestine. The gain to this cause is the greater since it is immediate, but perhaps more important still is the wide political influence which this Imperial action is like to have. It has not been generally reported that when the Kaiser visited Constantinople, Dr. Herzl, the head of the Zionist movement, was there; again when the Kaiser entered Jerusalem, he found Dr.Herzl there. These were no mere coincidences, but the visible signs of accomplished facts." Herzl had achieved political legitimacy.

- Reuben R Hecht, When the Shofar sounds, 2006, p. 43

- Herzl, Theodor (27 April 2012). The Jewish State. Courier Corporation. ISBN 9780486119618. Retrieved 17 August 2022 – via Google Books.

- "Time Line". Herzl.org. Archived from the original on 18 January 2012. Retrieved 26 October 2011.

- "Time Line". Herzl.org. Archived from the original on 18 January 2012. Retrieved 26 October 2011.

- Friedman, Isaiah. "Herzl, Theodor." Encyclopaedia Judaica. Ed. Michael Berenbaum and Fred Skolnik. 2nd ed. Vol. 9. Detroit: Macmillan Reference USA, 2007. 63. Gale Virtual Reference Library. Web. 22 January 2016

- 'Complete Diaries of Theodor Herzl' ed. Raphael Patai, transl. Harry Zohn, in 5 vols, (NY 1960), 5 July 1896 and 28 June 1895, i, p. 190

- Vital, p. 442

- in Der Judenstaat: Versuch einer modernen Losung der Judenfrage (An Attempt at a Modern Solution to the Jewish Question)

- transl. A Russian Jew's urgent warning to his kinsfolk

- "Theodor Herzl in Jerusalem, Just Prior to Meeting With German Emperor Wilhelm II..." Shapell Manuscript Foundation. Archived from the original on 25 April 2012. Retrieved 26 October 2011.

- Herzl had written in his diary of the necessity for world power recognition. 11 March 1896"

- Ginsberg, Michael Peled; Ron, Moshe (June 2004). Shattered Vessels: Memory, Identity, and Creation in the Work of David Shahar. State University of New York Press. ISBN 978-0-7914-5919-5.

- Kaiser Wilhelm II had assured Herzl of his support for the Jewish protectorate under Germany when they had met privately in Istanbul a week earlier. By the time of their public meetings at Mikveh Israel and Jerusalem, the Kaiser had changed his mind. Herzl had thought he had failed. In the eyes of public opinion he had not.

- Schneer, The Balfour Declaration, p. 111

- Schneer, p. 112

- Catholicism, France and Zionism: 1895–1904 Archived 13 July 2007 at the Wayback Machine

- Laqueur, Walter. The History of Zionism. London: Tauris Parke Paperbacks, 2003. p. 111

- Schneer, pp. 113–14

- David Vital, A People and a State (1999), p. 448

- Elon, Amos (1975). Herzl, pp. 400–01, New York: Holt, Rinehart and Winston. ISBN 978-0-03-013126-4.

- 'Obituary', The Times, Thursday, 7 July 1904; p. 10; Issue 37440; col B.

- Elon, Amos (1975). Herzl, p. 402, New York: Holt, Rinehart and Winston. ISBN 978-0-03-013126-4.

- Corbett, Tim (2016). ""Was ich den Juden war, wird eine kommende Zeit besser beurteilen …" - Myth and Memory at Theodor Herzl's Original Gravesite in Vienna". S:I.M.O.N. Shoah: Intervention. Methods. Documentation. 3 (1): 64–88. ISSN 2408-9192.

- Mystery solved: Missing Herzl Parochet found in the KKL-JNF House in Tel Aviv, Jerusalem Post

- "Knesset Creates Herzl Day".

- Desmond Stewart (1974) Theodor Herzl. Artist and Politician. Hamish Hamilton SBN 241 02447 1 p.109

- Stewart (1974) pp.323,339

- Elon, Amos (1975) Herzl. Holt, Rinehart and Winston. ISBN 0-03-013126-X p.49

- Stewart p.339

- "Eda Zoritte-Megged". The Institute for the Translation of Hebrew Literature. Retrieved 17 October 2019.

- Elon, Amos (1975). Herzl, p. 403, New York: Holt, Rinehart and Winston. ISBN 978-0-03-013126-4.

- Rogaia Mustafa Abusharaf,Female Circumcision: Multicultural Perspectives, (University of Pennsylvania Press, 2007), p. 51

- The Gender Of Desire: Essays On Male Sexuality, By Michael S. Kimmel, SUNY Press, 2005, p. 181

- Stewart, D., Theodor Herzl (Garden City, New York: Doubleday, 1974), p. 202

- "Einstein on Theodor Herzl's Son, Hans' Conversion and Suicide". Shapell Manuscript Collection. SMF.

- Princes Without a Home: Modern Zionism and the Strange Fate of Theodor Herzl's children, Ilse Sternberger, p. 125

- Rabbi Ken Spiro (2 February 2002). "Crash Course in Jewish History Part 63 – Modern Zionism". Aish HaTorah. Retrieved 26 October 2011.

- Princes Without a Home, by Isle Sternberger

- "Manta – Rediscover America's Small Business". Manta. Goliath.ecnext.com. Retrieved 26 October 2011.

- Herzl's children to be disinterred on Tuesday in Bordeaux, France haaretz.com Archived 5 September 2008 at the Wayback Machine

- Fulfilling Historical Justice: Herzl's Children Come Home, jewishagency.org Archived 8 January 2009 at the Wayback Machine

- Zionist Archives letters of Richard Neumann

- Stephen Norman, 'Airstop in Israel' azure.org.il

- Central Zionist Archives-extensive documentary exchange between Lauterbach and Norman 1936–1946

- Central Zionist Archives, Jerusalem, Papers of Stephen Norman, 2 July 1946, letter to Mrs.Stybovitz-Kahn

- Haboker 26 October 1945. Document amongst the papers of Stephen Norman at the Central Zionist Archives in Jerusalem

- Central Zionist Archives, Jerusalem, August 1946,

- "These Children Bore the Mark of Freedom," by Jerry Klinger, Theodor Herzl Foundation, in Midstream, a bi-monthly Jewish review, May/June 2007, pp. 21–24, ISSN 0026-332X

- Anshel Pfeffer and Haaretz Service (5 December 2007). "Theodor Herzl's only grandson reinterred in J'lem cemetery". Haaretz.com.

- Richard Greenberg, Washington Jewish Week, 27 June 2007, "Zionist set to come 'home': Herzl's grandson slated to be reburied in Israel"

- Jerry Klinger, "A Zionist who deserves to come home", Jerusalem Post, 12 February 2003 Crash Course in Jewish History Part 63 – Modern Zionism at www.aish.com

- Guttman, Nathan (29 August 2007). "Jerusalem Plans a Hero's Burial to Long Deceased Grandson of Herzl". The Jewish Daily Forward.

- Jerry Klinger, President of the Jewish American Society for Historic Preservation, was the principle organizer behind the five-year reburial effort.

- "Jewish-american-society-for-historic-preservation.org". Jewish American Society for Historic Preservation. 5 December 2007. Retrieved 26 October 2011.

- Cleveland, William L. A History of the Modern Middle East. Boulder, CO: Westview, 2004. Print. p. 223

- "Jewishvirtuallibrary.org". Jewishvirtuallibrary.org. Retrieved 26 October 2011.

- Avineri, Shlomo (2 September 2009). "Herzl's vision of racism". Haaretz. Archived from the original on 17 April 2009. Retrieved 8 August 2009.

- "Henry George and Zionism". Jewish Currents. Archived from the original on 18 October 2015. Retrieved 24 February 2015.

- 'Zion & the Jewish National Idea', in Zionism Reconsidered, Macmillan, 1970 PB, p.185

- "Brandeis.edu". Brandeis.edu. 24 May 2010. Retrieved 26 October 2011.

- L.C.M. van der Hoeven Leonhard, 'Shlomo and David, Israel, 1907', in From Haven to Conquest, 1971, W. Khalidi (ed.), pp. 118–19.

- 'The Complete Diaries of Theodor Herzl', vol. 1 (New York: Herzl Press and Thomas Yoseloff, 1960), pp. 88, 90 hereafter Herzl diaries.

- "Theodor Herzl 1880-1889 | The Jewish Agency". archive.jewishagency.org. Retrieved 17 August 2022.

- "Theodor Herzl 2004". The Department for Jewish Zionist Education. Archived from the original on 14 January 2005. Retrieved 8 August 2009.

- Balsam, Mashav. "Theodor Herzl: From the Theatre Stage to The Stage of Life". All About Jewish Theatre. Archived from the original on 12 June 2010. Retrieved 8 August 2009.

Further reading

Primary and secondary sources

- Peres, Shimon (1999). The imaginary voyage : with Theodor Herzl in Israel (1st English-language ed.). New York: Arcade Publishing. ISBN 978-1559704687. OCLC 40925994.

Biographies of Theodor Herzl

- Avineri, Shlomo (2013). Herzl: Theodor Herzl and the Foundation of the Jewish State. London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson. ISBN 978-0297868804.

- Falk, Avner (1993). Herzl, King of the Jews: A Psychoanalytic Biography of Theodor Herzl. Washington: University Press of America. ISBN 978-0-8191-8925-7.

- Elon, Amos (1975). Herzl. New York: Holt, Rinehart and Winston. ISBN 978-0-03-013126-4.

- Alex Bein (1934). Theodor Herzl: Biographie. mit 63 Bildern und einer Ahnentafel, de icon.

- Bein, Alex (1941). Maurice Samuel (ed.). Theodor Herzl: A Biography of the Founder of the Modern Zionism.

- Leon Kellner (1920). Theodor Herzls Lehrjahre 1860–1895. Vienna.

- Beller, Steven (2004). Herzl.

- Stewart, Desmond (1974). Theodor Herzl. Artist and Politician.

- Pawel, Ernst (1992). The Labyrinth of Exile: A Life of Theodor Herzl.

Articles

- Avineri, Shlomo (1999). "Herzl's Diaries as a Bildungsroman". Jewish Social Studies. 3 (2): 1–46. doi:10.2979/JSS.1999.5.3.1. S2CID 161154754.

- Epstein, Joseph (Summer 2020), "The Moses of His Day: How Theodor Herzl became the unlikely father of Zionism," Claremont Review of Books

- Friedman, Isaiah (2004). "Theodor Herzl: Political Activity and Achievements". Israel Studies. 9 (3): 46–79, online in EBSCO. doi:10.2979/ISR.2004.9.3.46. S2CID 144334424.

- Kornberg, Jacques (June 1980). "Theodor Herzl: A Reevaluation". Journal of Modern History. 52 (2): 226–252. doi:10.1086/242094. JSTOR 1878229. S2CID 144647248.

Films

- Otto Kreisler. Theodor Herzl.

External links

- Literature by and about Theodor Herzl in University Library JCS Frankfurt am Main: Digital Collections Judaica

- On Herzl's Diaries, Shlomo Avineri

- Original Letters and Primary Sources from Theodor Herzl Shapell Manuscript Foundation

- About Israel – Herzl Now Archived 5 October 2013 at the Wayback Machine

- Works by Herzl in German at German-language Wikisource

- Zionism and the creation of modern Israel

- Biography of Theodor Herzl

- Herzl family

- The personal papers of Theodor Herzl are kept at the Central Zionist Archives in Jerusalem

- Famous Hungarian Jews: Herzl Tivadar

- Theodor Herzl: Visions of Israel, Video Lecture by Dr. Henry Abramson

- Works by Theodor Herzl at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about Theodor Herzl at Internet Archive

- Works by Theodor Herzl at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

- Theodor Herzl Personal Manuscripts and Letters

- "Text der Gesänge zu Des Teufels Weib : phantastisches Singspiel in 3 Acten und einem Vorspiel" by Theodor Herz and Adolf Müller Jr. in the Library of Congress

- Newspaper clippings about Theodor Herzl in the 20th Century Press Archives of the ZBW

.jpg.webp)

.jpg.webp)