Tigranes the Great

Tigranes II, more commonly known as Tigranes the Great (Armenian: Տիգրան Մեծ, Tigran Mets;[5] Ancient Greek: Τιγράνης ὁ Μέγας Tigránes ho Mégas; Latin: Tigranes Magnus)[6] (140 – 55 BC) was King of Armenia under whom the country became, for a short time, the strongest state to Rome's east. He was a member of the Artaxiad Royal House. Under his reign, the Armenian kingdom expanded beyond its traditional boundaries, allowing Tigranes to claim the title Great King, and involving Armenia in many battles against opponents such as the Parthian and Seleucid empires, and the Roman Republic.

| Tigranes the Great | |

|---|---|

| King of Kings | |

Coin of Tigranes, Antioch mint. The star symbol between the two eagles on his crown may depict Halley's Comet.[1] | |

| King of Armenia | |

| Reign | 95–55 BC |

| Predecessor | Tigranes I |

| Successor | Artavasdes II |

| Born | 140 BC |

| Died | 55 BC (aged 85) |

| Burial | |

| Consort | Cleopatra of Pontus |

| Issue | Four sons: Zariadres Unnamed Tigranes Artavasdes II Three daughters: Ariazate unnamed unnamed |

| Dynasty | Artaxiad |

| Father | Artavasdes I or Tigranes I |

| Mother | Alan princess[2] |

| Religion | Zoroastrianism[3][4] |

Early years

In approximately 120 BC, the Parthian king Mithridates II (r. 124–91 BC) invaded Armenia and made its king Artavasdes I acknowledge Parthian suzerainty.[7] Artavasdes I was forced to give the Parthians Tigranes, who was either his son or nephew, as a hostage.[7][8] Tigranes lived in the Parthian court at Ctesiphon, where he was schooled in Parthian culture.[2] Tigranes remained a hostage at the Parthian court until c. 96/95 BC, when Mithridates II released him and appointed him as the king of Armenia.[9][10] Tigranes ceded an area called "seventy valleys" in the Caspiane to Mithridates II, either as a pledge or because Mithridates II demanded it.[11] Tigranes' daughter Ariazate had also married a son of Mithridates II, which has been suggested by the modern historian Edward Dąbrowa to have taken place shortly before he ascended the Armenian throne as a guarantee of his loyalty.[10] Tigranes would remain a Parthian vassal until the end of the 80's BC.[12]

When he came to power, the foundation upon which Tigranes was to build his Empire was already in place, a legacy of the founder of the Artaxiad Dynasty, Artaxias I, and subsequent kings. The mountains of Armenia, however, formed natural borders between the different regions of the country and as a result, the feudalistic nakharars had significant influence over the regions or provinces in which they were based. This did not suit Tigranes, who wanted to create a centralist empire. He thus proceeded by consolidating his power within Armenia before embarking on his campaign.[13]

He deposed Artanes, the last king of the Kingdom of Sophene and a descendant of Zariadres.[14]

Alliance with Pontus

During the First Mithridatic War (89–85 BC), Tigranes supported Mithridates VI of Pontus, but was careful not to become directly involved in the war.

He rapidly built up his power and established an alliance with Mithridates VI, marrying his daughter Cleopatra. Tigranes agreed to extend his influence in the East, while Mithridates set to conquer Roman land in Asia Minor and in Europe. By creating a stronger Hellenistic state, Mithridates was to contend with the well-established Roman foothold in Europe.[13] Mithridates executed a planned general attack on Romans and Italians in Asia Minor, tapping into local discontent with the Romans and their taxes and urging the peoples of Asia Minor to raise against foreign influence. The slaughter of 80,000 people in the province of Asia Minor was known as the Asiatic Vespers. The two kings' attempts to control Cappadocia and then the massacres resulted in guaranteed Roman intervention. The senate decided that Lucius Cornelius Sulla, who was then one of the consuls, would command the army against Mithridates.[15]

The renowned French historian René Grousset remarked that in their alliance Mithridates was somewhat subservient to Tigranes.[16]

Wars against the Parthians and Seleucids

After the death of Mithridates II of Parthia his son Gotarzes I succeeded him.[17] He reigned during a period coined in scholarship as the "Parthian Dark Age," due to the lack of clear information on the events of this period in the empire, except a series of, apparently overlapping, reigns.[18][19] This system of split monarchy weakened Parthia, allowing Tigranes II of Armenia to annex Parthian territory in western Mesopotamia. This land would not be restored to Parthia until the reign of Sinatruces (r. c. 78–69 BC).[20]

The changes of fortune experienced by Tigranes were varied, for at first he was a hostage among the Parthians; and then through them he obtained the privilege of returning home, they receiving as reward therefore seventy valleys in Armenia; but when he had grown in power, he not only took these places back but also devastated their country, both that about Ninus (Nineveh), and that about Arbela; and he subjugated to himself the rulers of Atropene and Gordyaea (on the Upper Tigris), and along with these the rest of Mesopotamia, and also crossed the Euphrates and by main strength took Syria itself and Phoenicia —Strabo[21]

In 83 BC, after bloody strife for the throne of Syria, governed by the Seleucids, the Syrians decided to choose Tigranes as the protector of their kingdom and offered him the crown of Syria.[22] Magadates was appointed as his governor in Antioch.[23] He then conquered Phoenicia and Cilicia, effectively putting an end to the last remnants of the Seleucid Empire, though a few holdout cities appear to have recognized the shadowy boy-king Seleucus VII Philometor as the legitimate king during his reign. The southern border of his domain reached as far as Ptolemais (modern Akko). Many of the inhabitants of conquered cities were sent to his new metropolis of Tigranocerta.

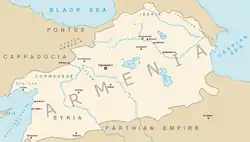

At its height, his empire extended from the Pontic Alps (in modern north-eastern Turkey) to Mesopotamia, and from the Caspian Sea to the Mediterranean. A series of victories led him to assume the Achaemenid title of King of Kings, which even the Parthian kings did not assume, appearing on coins struck after 85 BC.[24] He was called "Tigranes the Great" by many Western historians and writers, such as Plutarch. The "King of Kings" never appeared in public without having four kings attending him. Cicero, referring to his success in the east, said that he "made the Republic of Rome tremble before the prowess of his arms."[25]

Tigranes' coins consist of tetradrachms and copper coins having on the obverse his portrait wearing a decorated Armenian tiara with ear-flaps. The reverse has a completely original design. There are the seated Tyche of Antioch and the river god Orontes at her feet.

Wars against Rome

Mithridates VI of Pontus had found refuge in Armenian land after confronting Rome, considering the fact that Tigranes was his ally and relative. The King of Kings eventually came into direct contact with Rome. The Roman commander, Lucullus, demanded the expulsion of Mithridates from Armenia – to comply with such a demand would be, in effect, to accept the status of vassal to Rome and this Tigranes refused.[26] Charles Rollin, in his Ancient History, says:

Tigranes, to whom Lucullus had sent an ambassador, though of no great power in the beginning of his reign, had enlarged it so much by a series of successes, of which there are few examples, that he was commonly surnamed "King of Kings." After having overthrown and almost ruined the family of the kings, successors of the great Seleucus; after having very often humbled the pride of the Parthians, transported whole cities of Greeks into Media, conquered all Syria and Palestine, and given laws to the Arabians called Scenites, he reigned with an authority respected by all the princes of Asia. The people paid him honors after the manners of the East, even to adoration.[27]

Lucullus' reaction was an attack that was so precipitate that he took Tigranes by surprise. According to Roman historians Mithrobazanes, one of Tigranes' generals, told Tigranes of the Roman approach. Tigranes was, according to Keaveney, so impressed by Mithrobazanes' courage that he appointed Mithrobazanes to command an army against Lucullus – Tigranes sent Mithrobarzanes with 2,000 to 3,000 cavalry to expel the invader. Mithrobarzanes charged the Romans while they were setting up their camp, but was met by a 3,500-strong sentry force and his horsemen were routed. He perished in the attempt.[28][29] After this defeat, Tigranes withdrew north to Armenia to regroup, leaving Lucullus free to besiege Tigranocerta.[30]

When Tigranes had gathered a large army, he returned to confront Lucullus. On October 6, 69 BC, Tigranes' much larger force was decisively defeated by the Roman army under Lucullus in the Battle of Tigranocerta. Tigranes' treatment of the inhabitants (the majority of the population had been forced to move to the city) led disgruntled city guards to open the gates of the city to the Romans. Learning of this, Tigranes hurriedly sent 6000 cavalrymen to the city in order to rescue his wives and some of his assets.[13] Tigranes escaped capture with a small escort.

On October 6, 68 BC, the Romans approached the old capital of Artaxata. Tigranes' and Mithridates' combined Armeno-Pontic army of 70,000 men formed up to face them but were resoundingly defeated. Once again, both Mithridates and Tigranes evaded capture by the victorious Romans. However, the Armenian historians claim that the Romans lost the battle of Artaxata and Lucullus' following withdrawal from the Kingdom of Armenia in reality was an escape due to the above-mentioned defeat. The Armenian-Roman wars are depicted in Alexandre Dumas' Voyage to the Caucasus.

The long campaigning and hardships that Lucullus' troops had endured for years, combined with a perceived lack of reward in the form of plunder,[13] led to successive mutinies among the legions in 68–67. Frustrated by the rough terrain of Northern Armenia and seeing the worsening morale of his troops, Lucullus moved back south and put Nisibis under siege. Tigranes concluded (wrongly) that Nisibis would hold out and sought to regain those parts of Armenia that the Romans had captured.[31] Despite his continuous success in battle, Lucullus could still not capture either one of the monarchs. With Lucullus' troops now refusing to obey his commands, but agreeing to defend positions from attack, the Senate sent Pompey to recall Lucullus to Rome and take over his command.

Pompey and submission to Rome

In 67 BC[32] Pompey was given the task of defeating Mithridates and Tigranes.[33] Pompey first concentrated on attacking Mithridates while distracting Tigranes by engineering a Parthian attack on Gordyene.[34] Phraates III, the Parthian king, was soon persuaded to take things a little further than an annexation of Gordyene when a son of Tigranes (also named Tigranes) went to join the Parthians and persuaded Phraates to invade Armenia in an attempt to replace the elder Tigranes with the Tigranes the Younger.[35] Tigranes decided not to meet the invasion in the field but instead ensured that his capital, Artaxata, was well defended and withdrew to the hill country. Phraates soon realized that Artaxata would not fall without a protracted siege, the time for which he could not spare due to his fear of plots at home. Once Phraates left, Tigranes came back down from the hills and drove his son from Armenia. The son then fled to Pompey.[36]

In 66 BC, Pompey advanced into Armenia with Tigranes the Younger, and Tigranes, now almost 75 years old, surrendered. Pompey allowed him to retain his kingdom shorn of his conquests as he planned to have Armenia as a buffer state[37][38] and he took 6,000 talents/180 tonnes of silver. His unfaithful son was sent back to Rome as a prisoner.[39]

Tigranes continued to rule Armenia as a formal ally of Rome until his death in 55/54,[38] at age 85.

Offspring

Tigranes had four sons and three daughters.[40][41] The eldest son, Zariadres, according to Appian and Valerius Maximus rebelled against Tigranes and was killed during a battle (possibly late 90s BCE).[42][43] Appian also mentions an unnamed younger son who was executed for conspiring against Tigranes: he disregarded his father's health and wore Tigranes's crown (Tigranes having been injured during a hunting accident).[44] His third son, Tigranes the Younger, who showed great care for his injured father and was rewarded for his loyalty,[44] has already been mentioned. He is also alleged to have led a military campaign in 82 BCE.[44] Tigranes was succeeded by his fourth and youngest son, Artavasdes II.

One daughter of Tigranes according to Cassius Dio married Mithridates I of Atropatene.[40][45] Another daughter married Parthian prince Pacorus, son of Orodes II.[41][46] Parchments of Avroman also mention his third daughter, Ariazate "Automa", who married Gotarzes I of Parthia.[3][46]

Although Cleopatra of Pontus is usually considered to be their mother (Appian writes that she gave birth to three sons),[44] historian Gagik Sargsyan considered only Artavasdes II and one of the unnamed daughters to be her children.[47] According to him, the rest had a different mother and were born before Tigranes became king.[48] The reasoning behind it is that if Tigranes the Younger did indeed lead a campaign in 82 BCE, then he and hence his two older brothers (and possibly two sisters) would be too old to be Cleopatra's children.[48] Another argument supporting this claim would be the situation with Ariazate. As she was probably the mother of Orodes I (r. 80–75 BC),[49] then Ariazate could not have been the daughter of Cleopatra who married Tigranes only in 94 BCE at the age of 15 or 16.[50] Sargsyan also proposed a possible candidate as Tigranes's first wife and the children's mother: Artaxiad princess Zaruhi, a daughter of Tigranes's paternal uncle Zariadres and granddaughter of Artaxias I.[50] He also considered likely that the reason for the rebellion of Tigranes's son Zariadres was the birth of Artavasdes who was declared the heir by virtue of being born to a king and not a prince.[51]

Imperial ideology

Tigranes is a typical example of the mixed culture of his period. The ceremonial of his court was of Achaemenid origin, and also incorporated Parthian aspects.[3] He had Greek rhetoricians and philosophers in his court, possibly as a result of the influence of his queen, Cleopatra.[3] Greek was also possibly spoken in the court.[3] Following the example of the Parthians, Tigranes adopted the title of Philhellene ("friend of the Greeks").[3] The layout of his capital Tigranocerta was a blend of Greek and Iranian architecture.[3]

Like the majority Armenia's inhabitants, Tigranes was a follower of Zoroastrianism.[lower-alpha 1][3][52] On his crown, a star of divinity and two birds of prey are displayed, both Iranian aspects.[3][53] The bird of prey was associated with the khvarenah, i.e. kingly glory.[53] It was possibly also a symbol of the bird of the deity Verethragna.[53]

Legacy and recognition

.png.webp)

Over the course of his conquests, Tigranes founded four cities that bore his name, including the capital of Tigranocerta (Tigranakert).[55]

Historical

Tigranes is mentioned in Macrobii, a Roman essay detailing the famous long livers of the day, which is attributed to Lucian.[56]

In The Art of War (1521), Italian political philosopher Niccolò Machiavelli attributes Tigranes' military failure to his excessive reliance on his cavalry.[57]

According to one count, 24 operas have been composed about Tigranes by European composers,[58] including by prominent Italian and German composers, such as Alessandro Scarlatti (Tigrane, 1715), Antonio Vivaldi (La virtu trionfante dell'amore e dell'odio ovvero il Tigrane, 1724),[59] Niccolò Piccinni (Tigrane, 1761), Tomaso Albinoni, Giovanni Bononcini, Francesco Gasparini, Pietro Alessandro Guglielmi, Johann Adolph Hasse, Giovanni Battista Lampugnani, Vincenzo Righini, Antonio Tozzi, and others.[60]

Modern

According to Razmik Panossian, Tigranes' short-lived empire has been a source of pride for modern Armenian nationalists.[61] Nevertheless, his empire was a multi-ethnic one.[62]

The phrase "sea to sea Armenia" (Armenian: ծովից ծով Հայաստան, tsovits tsov Hayastan) is a popular expression used by Armenians to refer to the kingdom of Tigranes which extended from the Caspian Sea to the Mediterranean Sea.[63][64]

See also

Notes

- The largest expansion took place during the reign of Tigran (II) the Great, who ruled between 95 and 55 bce and whose empire at one time stretched from the Mediterranean to the Caspian Sea...The court ceremonial was Achaemenid, containing also Parthian elements. However, perhaps due to the influence of the queen, Cleopatra of Pontus, there were Greek rhetoricians and philosophers at court..[..]..At court Greek may have been spoken; Tigran's heir Artawazd II wrote his plays and other literary works, which were still known in the second century ce...Tigran's religion was probably Mazdaism, a variety of Zoroastrianism."[3]

References

- Gurzadyan, V. G.; Vardanyan, R. (August 2004). "Halley's comet of 87 BC on the coins of Armenian king Tigranes?". Astronomy & Geophysics. 45 (4): 4.06. arXiv:physics/0405073. Bibcode:2004A&G....45d...6G. doi:10.1046/j.1468-4004.2003.45406.x. S2CID 119357985.

- Mayor 2009, p. 136.

- Romeny 2010, p. 264.

- Curtis 2016, p. 185; de Jong 2015, pp. 119–120, 123–125; Chaumont 1986, pp. 418–438

- Western Armenian pronunciation: Dikran Medz

- Ubbo Emmius (1620). Appendix Genealogica: illustrando operi chronologico adjecta. Excudebat Ioannes Sassivs. p. D5.

- Olbrycht 2009, p. 165.

- Garsoian 2005.

- Olbrycht 2009, p. 168.

- Dąbrowa 2018, p. 78.

- Olbrycht 2009, pp. 165, 182 (see note 57).

- Olbrycht 2009, p. 169.

- Kurdoghlian, Mihran (1996). Պատմութիւն Հայոց [History of Armenia, Volume I] (in Armenian). Athens: Council of National Education Publishing. pp. 67–76.

- Strabo. Geographica, 11.14.15.

- Appian. The Civil Wars, 1.55.

- René Grousset (1946), Histoire de l'Arménie (in French), Paris, p. 85,

Dans l'alliance qui fut alors conclus entre les deux souverains, Mithridates faisait un peu figure client de Tigran.

- Assar 2006, p. 62; Shayegan 2011, p. 225; Rezakhani 2013, p. 770

- Shayegan 2011, pp. 188–189.

- Sellwood 1976, p. 2.

- Brosius 2006, pp. 91–92

- Strabo. Geographica 11.14.15, .

- Litovchenko 2015, p. 179–188.

- The House Of Seleucus V2 by Edwyn Robert Bevan.

- Theo Maarten van Lint (2009). "The Formation of Armenian Identity in the First Millennium". Church History and Religious Culture. 89 (1/3): 264.

- Boyajian, Zabelle C. (1916). An Anthology of Legends and Poems of Armenia. Aram Raffi; Viscount Bryce. London: J.M. Dent & sons, Ltd. p. 117.

- Greenhalgh 1981, p. 74.

- Rollins, Charles (1844). Ancient History, vol. 4: History of the Macedonians, the Seleucidae in Syria, and Parthians. New York: R. Carter. p. 461.

- Philip Matyszak, Mithridates the Great, pp 127-128; Lee Frantatuono, Lucullus, pp 83-84; Plutarch, Life of Lucullus, XII.84.

- Keaveney 1992, pp. 106–107.

- Keaveney 1992, p. 107.

- Keaveney 1992, p. 119.

- The Encyclopaedia of Military History, R E Dupuy and T N Dupuy

- Greenhalgh 1981, p. 105.

- Greenhalgh 1981, p. 105, 114.

- Greenhalgh 1981, p. 114.

- Greenhalgh 1981, p. 115.

- Scullard, H.H. (1959). From the Gracchi to Nero: A History of Rome from 133 B.C. to A.D. 68. New York: F.A. Praeger. p. 106.

- Fuller, J.F.C. (1965). Julius Caesar: Man, Soldier, and Tyrant. London: Eyre & Spottiswoode. p. 45. ISBN 978-0-306-80422-9.

- Chaumont, M. L. (2001–2002). "Tigrane le Jeune, fils de Tigrane le Grand". Revue des Études Arméniennes (in French). 28: 225–247.

- Sargsyan 1991, p. 51.

- Redgate 2000, p. 77.

- Sargsyan 1991, p. 49, 52.

- Valerius Maximus. Factorum ac dictorum memorabilium libri IX, Liber IX, ext.3.

- Sargsyan 1991, p. 49.

- Cassius Dio. The Roman History, XXXVI, 14.

- Minns 1915, p. 42.

- Sargsyan 1991, p. 51, 52.

- Sargsyan 1991, p. 50.

- Assar 2006, p. 67, 74.

- Sargsyan 1991, p. 53.

- Sargsyan 1991, p. 52.

- Curtis 2016, p. 185; de Jong 2015, pp. 119–120, 123–125

- Curtis 2016, pp. 182, 185.

- "Banknotes out of Circulation - 500 dram". cba.am. Central Bank of Armenia. Archived from the original on 19 February 2022.

The tetradrachm of the King Tigran the Great, mountain of Ararat

- Karapetian, Samvel (2001). Armenian Cultural Monuments in the Region of Karabakh. Yerevan: "Gitutiun" Publishing House of National Academy of Sciences of Armenia. p. 213. ISBN 9785808004689.

The data of records referring to these four towns, all of which were called Tigranakert and differed only by provinces, were often confused, if the name of the province; Aldznik, Goghtn, Utik or Artsakh...

- Lucian. Macrobii, 15.

- Payaslian, Simon (2007). The History of Armenia. New York: Palgrave Macmillan. p. 22. ISBN 978-1-4039-7467-9.

- Kharmandarian, M. S. (1975). Опера «Тигран» Алессандро Скарлатти. Lraber Hasarakakan Gitutyunneri (in Russian) (3): 59–69.

- "Vivaldi as opera composer". Long Beach Opera. Retrieved 31 August 2013.

- Towers, John (1910). Dictionary-catalogue of Operas and Operettas which Have Been Performed on the Public Stage: Libretti. Acme Publishing Company. pp. 625–6.

- Panossian, Razmik (2006). The Armenians: From Kings and Priests to Merchants and Commissars. New York: Columbia University Press. p. 42. ISBN 9780231139267.

- Kohl, Philip L. (2012). "Homelands in the Present and in the Past: Political Implications of a Dangerous Concept". In Hartley, Charles W.; Yazicioğlu, G. Bike; Smith, Adam T. (eds.). The Archaeology of Power and Politics in Eurasia: Regimes and Revolutions. Cambridge University Press. p. 149. ISBN 9781139789387.

- Verluise, Pierre (1995). Armenia in Crisis: The 1988 Earthquake. Detroit: Wayne State University Press. p. xxiv. ISBN 9780814325278.

- Coe, Barbara (2005). Changing Seasons: Letters from Armenia. Victoria, B.C.: Trafford. p. 215. ISBN 9781412070225.

Bibliography

- English

- Assar, Gholamreza F. (2006). A Revised Parthian Chronology of the Period 91-55 BC. Parthica. Incontri di Culture Nel Mondo Antico. Vol. 8: Papers Presented to David Sellwood. Istituti Editoriali e Poligrafici Internazionali. ISBN 978-8-881-47453-0. ISSN 1128-6342.

- Brosius, Maria (2006), The Persians: An Introduction, London & New York: Routledge, ISBN 978-0-415-32089-4.

- Dąbrowa, Edward (2018). "Arsacid Dynastic Marriages". Electrum. 25: 73–83. doi:10.4467/20800909EL.18.005.8925.

- Olbrycht, Marek Jan (2009). "Mithridates VI Eupator and Iran". In Højte, Jakob Munk (ed.). Mithridates VI and the Pontic Kingdom. Black Sea Studies. Vol. 9. Aarhus University Press. pp. 163–190. ISBN 978-8779344433. ISSN 1903-4873.

- Chaumont, M. L. (1986). "Armenia and Iran ii. The pre-Islamic period". Encyclopaedia Iranica, Vol. II, Fasc. 4. pp. 418–438.

- Garsoian, Nina (2004). "Armeno-Iranian Relations in the pre-Islamic period". Encyclopaedia Iranica.

- Garsoian, Nina (2005). "Tigran II". Encyclopaedia Iranica.

- Romeny, R. B. ter Haar (2010). Religious Origins of Nations?: The Christian Communities of the Middle East. Brill. ISBN 9789004173750.

- Seager, Robin (2008). Pompey the Great: A Political Biography. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 9780470775226.

- Keaveney, Arthur (1992). Lucullus: A Life. London: Routledge. ISBN 9781134968558.

- Greenhalgh, P. A. L. (1981). Pompey, the Roman Alexander, Volume 1. University of Missouri Press. ISBN 9780826203359.

- Walton Dobbins, K. (1974). "Mithradates II and his Successors: A Study of the Parthian Crisis 90-70 B.C.". Antichthon. 8: 63–79. doi:10.1017/S0066477400000447. ISSN 0066-4774.

- Traina, Giusto (2013). "Tigranu, the Crown Prince of Armenia": Evidence from the Babylonian Astronomical Diaries". Klio. 95 (2): 447–454. doi:10.1524/klio.2013.95.2.447. ISSN 2192-7669. S2CID 159478619.

- Downey, Glanville (1962). A History of Antioch in Syria. Princeton University Press. ISBN 9781400876716.

- Sullivan, Richard (1990). Near Eastern royalty and Rome, 100-30 BC. University of Toronto Press. ISBN 9780802026828.

- Brunner, C. J. (1983). "ADRAPANA". Encyclopaedia Iranica.

- Clive, Foss (1986). "The Coinage of Tigranes the Great: Problems, Suggestions and a New Find". The Numismatic Chronicle. 146: 19–66. ISSN 2054-9156. JSTOR 42667454.

- Christoph F., Konrad (1983). "Reges Armenii Patricios Resalutare Non Solent?". American Journal of Philology. 104 (3): 278–281. doi:10.2307/294542. ISSN 0002-9475. JSTOR 294542.

- Keaveney, Arthur (1981). "Roman Treaties with Parthia circa 95-circa 64 B.C". American Journal of Philology. 102 (2): 195–212. doi:10.2307/294311. ISSN 0002-9475. JSTOR 294311.

- Boccaccini, Gabriele (2012). "Tigranes the Great as "Nebuchadnezzar" in the Book of Judith". In Xeravits, Géza G. (ed.). A Pious Seductress: Studies in the Book of Judith. Berlin: Walter de Gruyter. pp. 55–69. ISBN 9783110279986..

- Dumitru, Adrian (2016). "Kleopatra Selene: A Look at the Moon and Her Bright Side". In Coşkun, Altay; McAuley, Alex (eds.). Seleukid Royal Women: Creation, Representation and Distortion of Hellenistic Queenship in the Seleukid Empire. Historia – Einzelschriften. Vol. 240. Franz Steiner Verlag. pp. 253–272. ISBN 978-3-515-11295-6. ISSN 0071-7665.

- Boyce, Mary (1984). Zoroastrians: Their Religious Beliefs and Practices. Psychology Press. pp. 1–252. ISBN 9780415239028.

- Curtis, Vesta Sarkhosh (2016). "Ancient Iranian Motifs and Zoroastrian Iconography". In Williams, Markus; Stewart, Sarah; Hintze, Almut (eds.). The Zoroastrian Flame Exploring Religion, History and Tradition. I.B. Tauris. pp. 179–203. ISBN 9780857728159.

- de Jong, Albert (2015). "Armenian and Georgian Zoroastrianism". In Stausberg, Michael; Vevaina, Yuhan Sohrab-Dinshaw; Tessmann, Anna (eds.). The Wiley Blackwell Companion to Zoroastrianism. John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.

- Russell, James R. (1987). Zoroastrianism in Armenia. Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0674968509.

- Minns, Ellis. H. (1915). "Parchments of the Parthian Period from Avroman in Kurdistan". The Journal of Hellenic Studies. 35: 22–65. doi:10.2307/624522. ISSN 0075-4269. JSTOR 624522.

- Redgate, Anne Elizabeth (2000). The Armenians. Wiley–Blackwell. ISBN 9780631143727.

- Mayor, Adrienne (2009). The Poison King: The Life and Legend of Mithradates, Rome's Deadliest Enemy. Princeton University Press. pp. 1–448. ISBN 9780691150260.

- Manandyan, Hakob (2007) [1943 in Russian]. Tigranes II and Rome: A New Interpretation Based on Primary Sources. Translated by George Bournoutian. Costa Mesa, CA: Mazda Publishers.

- Rezakhani, Khodadad (2013). "Arsacid, Elymaean, and Persid Coinage". In Potts, Daniel T. (ed.). The Oxford Handbook of Ancient Iran. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0199733309.

- Sellwood, David (1976). "The Drachms of the Parthian "Dark Age"". The Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain and Ireland. Cambridge University Press. 1 (1): 2–25. doi:10.1017/S0035869X00132988. JSTOR 25203669. (registration required)

- Shayegan, Rahim M. (2011), Arsacids and Sasanians: Political Ideology in Post-Hellenistic and Late Antique Persia, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0-521-76641-8

- Russian

- Hakobyan, Hayk (1983). "Тигранакертская битва в новом освещении (The battle of Tigranocerta under new light)". Herald of the Social Sciences. № 9: 65–79. ISSN 0320-8117.

- Litovchenko, Sergey (2015). "Царствование Тиграна II Великого в Сирии: проблемы хронологии (The reign of Tigranes the Great in Syria: chronology problems)". Ancient World and Archaeology. 17: 176–191. ISSN 0320-961X.

- Litovchenko, Sergey (2011). "Царство Софена в восточной политике Помпея (The kingdom of Sophene in the eastern policy of Pompey)". Drevnosti. 10: 34–40. OCLC 36974593.

- Litovchenko, Sergey (2007). Малая Армения и каппадокийские события 90-х гг. І в. до н. э. (Lesser Armenia and Cappadocian events in the 90s BC.). Laurea: K 80-letiju Professora Vladimira Ivanoviča Kadeeva. pp. 48–56. ISBN 9789663423876.

- Manandyan, Hakob (1943). Тигран Второй и Рим (Tigran II and Rome). Yerevan: Armfan.

- Manaseryan, R.L. (1982). "Процессы образования державы Тиграна II (The formation of the empire of Tigranes II)". Journal of Ancient History. 2: 122–139. ISSN 0321-0391.

- Manaseryan, R.L. (1985). "Борьба Тиграна против экспансии Рима в каппадокии 93-91 гг. до. н.э. (The struggle of Tigranes II against Roman expansion in Cappadocia)". Journal of Ancient History. 3: 109–118. ISSN 0321-0391.

- Manaseryan, R.L. (1992). "Международные отношения на Переднем Востоке в 80-70-х годах до н.э. (Тигран II и войска с берегов Аракса) International relations in the Near East. in the years 80-70 BC (Tigranes II and the troops from the banks of the Araxes)". Journal of Ancient History. 1: 152–160. ISSN 0321-0391.

- Sargsyan, Gagik (1991). "СВИДЕТЕЛЬСТВО ПОЗДНЕВАВИЛОНСКОЙ КЛИНОПИСНОЙ ХРОНИКИ ОБ АРМЕНИИ ВРЕМЕНИ ТИГРАНА II (Evidence Regarding Armenia during Tigran II' s Period in a Late Babylonian cuneiform chronicle)" (PDF). Patma-Banasirakan Handes (in Russian). 2: 45–54. ISSN 0135-0536.

- Vardanyan, Ruben (2011). "Борьба за титул "царя царей" в контексте восточной политики Рима I века до н. э. (по нумизматическим, эпиграфическим и нарративным источникам) ։ The Fight for the "King of Kings" Title in the Context of Rome's Eastern Policy in the 1st Century B. C. ( on numismatic, epigraphic and narrative sources)". Patma-Banasirakan Handes (1): 230–252. ISSN 0135-0536.

- French

- Duyrat, Frédérique (2012). "Tigrane en Syrie: un prince sans images". Cahiers des études anciennes. 49: 167–209. ISSN 0317-5065.

- Seyrig, Henri (1955). "Trésor monétaire de Nisibe". Revue numismatique: 85–128. ISSN 0317-5065.

- Sartre, Maurice (2014). "Syrie romaine (70 av. J.-C.-73 apr. J.-C.)". Pallas: Revue d'études antiques. 98 (96): 253–269. doi:10.4000/pallas.1284. ISSN 0031-0387.

- Thérèse, Frankfort (1963). "La Sophène Et Rome". Latomus. 22 (2): 181–190. ISSN 0023-8856.

- German

- Engels, David (2014). "Überlegungen zur Funktion der Titel "Großkönig" und "König der Könige". In Cojocaru, Victor; Coşkun, Altay; Dana, Mădălina (eds.). Interconnectivity in the Mediterranean and Pontic World during the Hellenistic and the Roman Periods. Romania: Cluj-Napoca. pp. 333–362. ISBN 9786065435261.

- Schottky, Martin (1989). Media Atropatene und Gross-Armenien in hellenistischer Zeit. Bonn: Habelt. ISBN 9783774923942.

- Armenian

- Manaseryan, Ruben (2007). Տիգրան Մեծ՝ Հայկական Պայքարը Հռոմի և Պարթևաստանի Դեմ, մ.թ.ա. 94–64 թթ [Tigran the Great: The Armenian Struggle Against Rome and Parthia, 94–64 B.C.] (in Armenian). Yerevan: Lusakan Publishing.