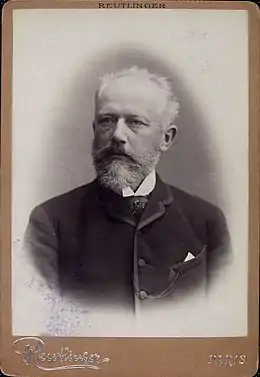

Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky

Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky[n 1] (/tʃaɪˈkɒfski/ chy-KOF-skee;[2] Russian: Пётр Ильи́ч Чайко́вский,[n 2] IPA: [pʲɵtr ɨˈlʲjitɕ tɕɪjˈkofskʲɪj] (![]() listen); 7 May 1840 – 6 November 1893)[n 3] was a Russian composer of the Romantic period. He was the first Russian composer whose music would make a lasting impression internationally. He wrote some of the most popular concert and theatrical music in the current classical repertoire, including the ballets Swan Lake and The Nutcracker, the 1812 Overture, his First Piano Concerto, Violin Concerto, the Romeo and Juliet Overture-Fantasy, several symphonies, and the opera Eugene Onegin.

listen); 7 May 1840 – 6 November 1893)[n 3] was a Russian composer of the Romantic period. He was the first Russian composer whose music would make a lasting impression internationally. He wrote some of the most popular concert and theatrical music in the current classical repertoire, including the ballets Swan Lake and The Nutcracker, the 1812 Overture, his First Piano Concerto, Violin Concerto, the Romeo and Juliet Overture-Fantasy, several symphonies, and the opera Eugene Onegin.

.png.webp)

Although musically precocious, Tchaikovsky was educated for a career as a civil servant as there was little opportunity for a musical career in Russia at the time and no system of public music education. When an opportunity for such an education arose, he entered the nascent Saint Petersburg Conservatory, from which he graduated in 1865. The formal Western-oriented teaching that he received there set him apart from composers of the contemporary nationalist movement embodied by the Russian composers of The Five with whom his professional relationship was mixed.

Tchaikovsky's training set him on a path to reconcile what he had learned with the native musical practices to which he had been exposed from childhood. From that reconciliation, he forged a personal but unmistakably Russian style. The principles that governed melody, harmony and other fundamentals of Russian music ran completely counter to those that governed Western European music, which seemed to defeat the potential for using Russian music in large-scale Western composition or for forming a composite style, and it caused personal antipathies that dented Tchaikovsky's self-confidence. Russian culture exhibited a split personality, with its native and adopted elements having drifted apart increasingly since the time of Peter the Great. That resulted in uncertainty among the intelligentsia about the country's national identity, an ambiguity mirrored in Tchaikovsky's career.

Despite his many popular successes, Tchaikovsky's life was punctuated by personal crises and depression. Contributory factors included his early separation from his mother for boarding school followed by his mother's early death; the death of his close friend and colleague Nikolai Rubinstein; and the collapse of the one enduring relationship of his adult life, his 13-year association with the wealthy widow Nadezhda von Meck, who was his patron even though they never met. His homosexuality, which he kept private, has traditionally also been considered a major factor though some musicologists now downplay its importance.[3] Tchaikovsky's sudden death at the age of 53 is generally ascribed to cholera, but there is an ongoing debate as to whether cholera was indeed the cause, and also whether the death was accidental or intentional.

While his music has remained popular among audiences, critical opinions were initially mixed. Some Russians did not feel it was sufficiently representative of native musical values and expressed suspicion that Europeans accepted the music for its Western elements. In an apparent reinforcement of the latter claim, some Europeans lauded Tchaikovsky for offering music more substantive than base exoticism and said he transcended stereotypes of Russian classical music. Others dismissed Tchaikovsky's music as "lacking in elevated thought"[4] and derided its formal workings as deficient because they did not stringently follow Western principles.

Life

Childhood

Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky was born in Votkinsk, a small town in Vyatka Governorate (present-day Udmurtia) in the Russian Empire, into a family with a long history of military service. His father, Ilya Petrovich Tchaikovsky, had served as a lieutenant colonel and engineer in the Department of Mines,[5] and would manage the Kamsko-Votkinsk Ironworks. His grandfather, Pyotr Fedorovich Tchaikovsky, was born in the village of Nikolayevka, Yekaterinoslav Governorate, Russian Empire (present-day Ukraine),[6] and served first as a physician's assistant in the army and later as city governor of Glazov in Vyatka. His great-grandfather,[7][8] a Zaporozhian Cossack named Fyodor Chaika, distinguished himself under Peter the Great at the Battle of Poltava in 1709.[9][10]

Tchaikovsky's mother, Alexandra Andreyevna (née d'Assier), was the second of Ilya's three wives, 18 years her husband's junior and French and German on her father's side.[11] Both Ilya and Alexandra were trained in the arts, including music—a necessity as a posting to a remote area of Russia also meant a need for entertainment, whether in private or at social gatherings.[12] Of his six siblings,[n 4] Tchaikovsky was close to his sister Alexandra and twin brothers Anatoly and Modest. Alexandra's marriage to Lev Davydov[13] would produce seven children[14] and lend Tchaikovsky the only real family life he would know as an adult,[15] especially during his years of wandering.[15] One of those children, Vladimir Davydov, who went by the nickname 'Bob', would become very close to him.[16]

In 1844, the family hired Fanny Dürbach, a 22-year-old French governess.[17] Four-and-a-half-year-old Tchaikovsky was initially thought too young to study alongside his older brother Nikolai and a niece of the family. His insistence convinced Dürbach otherwise.[18] By the age of six, he had become fluent in French and German.[12] Tchaikovsky also became attached to the young woman; her affection for him was reportedly a counter to his mother's coldness and emotional distance from him,[19] though others assert that the mother doted on her son.[20] Dürbach saved much of Tchaikovsky's work from this period, including his earliest known compositions, and became a source of several childhood anecdotes.[21]

Tchaikovsky began piano lessons at age five. Precocious, within three years he had become as adept at reading sheet music as his teacher. His parents, initially supportive, hired a tutor, bought an orchestrion (a form of barrel organ that could imitate elaborate orchestral effects), and encouraged his piano study for both aesthetic and practical reasons.

However, they decided in 1850 to send Tchaikovsky to the Imperial School of Jurisprudence in Saint Petersburg. They had both graduated from institutes in Saint Petersburg and the School of Jurisprudence, which mainly served the lesser nobility, and thought that this education would prepare Tchaikovsky for a career as a civil servant.[22] Regardless of talent, the only musical careers available in Russia at that time—except for the affluent aristocracy—were as a teacher in an academy or as an instrumentalist in one of the Imperial Theaters. Both were considered on the lowest rank of the social ladder, with individuals in them enjoying no more rights than peasants.[23]

His father's income was also growing increasingly uncertain, so both parents may have wanted Tchaikovsky to become independent as soon as possible.[24] As the minimum age for acceptance was 12 and Tchaikovsky was only 10 at the time, he was required to spend two years boarding at the Imperial School of Jurisprudence's preparatory school, 1,300 kilometres (800 mi) from his family.[25] Once those two years had passed, Tchaikovsky transferred to the Imperial School of Jurisprudence to begin a seven-year course of studies.[26]

Tchaikovsky's early separation from his mother caused an emotional trauma that lasted the rest of his life and was intensified by her death from cholera in 1854, when he was fourteen.[27][n 5] The loss of his mother also prompted Tchaikovsky to make his first serious attempt at composition, a waltz in her memory. Tchaikovsky's father, who had also contracted cholera but recovered fully, sent him back to school immediately in the hope that classwork would occupy the boy's mind.[28] Isolated, Tchaikovsky compensated with friendships with fellow students that became lifelong; these included Aleksey Apukhtin and Vladimir Gerard.[29]

Music, while not an official priority at school, also bridged the gap between Tchaikovsky and his peers. They regularly attended the opera[30] and Tchaikovsky would improvise at the school's harmonium on themes he and his friends had sung during choir practice. "We were amused," Vladimir Gerard later remembered, "but not imbued with any expectations of his future glory".[31] Tchaikovsky also continued his piano studies through Franz Becker, an instrument manufacturer who made occasional visits to the school; however, the results, according to musicologist David Brown, were "negligible".[32]

In 1855, Tchaikovsky's father funded private lessons with Rudolph Kündinger and questioned him about a musical career for his son. While impressed with the boy's talent, Kündinger said he saw nothing to suggest a future composer or performer.[33] He later admitted that his assessment was also based on his own negative experiences as a musician in Russia and his unwillingness for Tchaikovsky to be treated likewise.[34] Tchaikovsky was told to finish his course and then try for a post in the Ministry of Justice.[35]

Civil service; pursuing music

On 10 June 1859, the 19-year-old Tchaikovsky graduated as a titular counselor, a low rung on the civil service ladder. Appointed to the Ministry of Justice, he became a junior assistant within six months and a senior assistant two months after that. He remained a senior assistant for the rest of his three-year civil service career.[36]

Meanwhile, the Russian Musical Society (RMS) was founded in 1859 by the Grand Duchess Elena Pavlovna (a German-born aunt of Tsar Alexander II) and her protégé, pianist and composer Anton Rubinstein. Previous tsars and the aristocracy had focused almost exclusively on importing European talent.[37] The aim of the RMS was to fulfil Alexander II's wish to foster native talent.[38] It hosted a regular season of public concerts (previously held only during the six weeks of Lent when the Imperial Theaters were closed)[39] and provided basic professional training in music.[40] In 1861, Tchaikovsky attended RMS classes in music theory taught by Nikolai Zaremba at the Mikhailovsky Palace (now the Russian Museum).[41] These classes were a precursor to the Saint Petersburg Conservatory, which opened in 1862. Tchaikovsky enrolled at the Conservatory as part of its premiere class. He studied harmony and counterpoint with Zaremba and instrumentation and composition with Rubinstein.[42]

The Conservatory benefited Tchaikovsky in two ways. It transformed him into a musical professional, with tools to help him thrive as a composer, and the in-depth exposure to European principles and musical forms gave him a sense that his art was not exclusively Russian or Western.[43] This mindset became important in Tchaikovsky's reconciliation of Russian and European influences in his compositional style. He believed and attempted to show that both these aspects were "intertwined and mutually dependent".[44] His efforts became both an inspiration and a starting point for other Russian composers to build their own individual styles.[45]

Rubinstein was impressed by Tchaikovsky's musical talent on the whole and cited him as "a composer of genius" in his autobiography.[46] He was less pleased with the more progressive tendencies of some of Tchaikovsky's student work.[47] Nor did he change his opinion as Tchaikovsky's reputation grew.[n 6][n 7] He and Zaremba clashed with Tchaikovsky when he submitted his First Symphony for performance by the Russian Musical Society in Saint Petersburg. Rubinstein and Zaremba refused to consider the work unless substantial changes were made. Tchaikovsky complied but they still refused to perform the symphony.[48] Tchaikovsky, distressed that he had been treated as though he were still their student, withdrew the symphony. It was given its first complete performance, minus the changes Rubinstein and Zaremba had requested, in Moscow in February 1868.[49]

Once Tchaikovsky graduated in 1865, Rubinstein's brother Nikolai offered him the post of Professor of Music Theory at the soon-to-open Moscow Conservatory. While the salary for his professorship was only 50 rubles a month, the offer itself boosted Tchaikovsky's morale and he accepted the post eagerly. He was further heartened by news of the first public performance of one of his works, his Characteristic Dances, conducted by Johann Strauss II at a concert in Pavlovsk Park on 11 September 1865 (Tchaikovsky later included this work, re-titled Dances of the Hay Maidens, in his opera The Voyevoda).[50]

From 1867 to 1878, Tchaikovsky combined his professorial duties with music criticism while continuing to compose.[51] This activity exposed him to a range of contemporary music and afforded him the opportunity to travel abroad.[52] In his reviews, he praised Beethoven, considered Brahms overrated and, despite his admiration, took Schumann to task for poor orchestration.[53][n 8] He appreciated the staging of Wagner's Der Ring des Nibelungen at its inaugural performance in Bayreuth (Germany), but not the music, calling Das Rheingold "unlikely nonsense, through which, from time to time, sparkle unusually beautiful and astonishing details".[54] A recurring theme he addressed was the poor state of Russian opera.[55]

Relationship with The Five

In 1856, while Tchaikovsky was still at the School of Jurisprudence and Anton Rubinstein lobbied aristocrats to form the Russian Musical Society, critic Vladimir Stasov and an 18-year-old pianist, Mily Balakirev, met and agreed upon a nationalist agenda for Russian music, one that would take the operas of Mikhail Glinka as a model and incorporate elements from folk music, reject traditional Western practices and use non-Western harmonic devices such as the whole tone and octatonic scales.[56] They saw Western-style conservatories as unnecessary and antipathetic to fostering native talent.[57]

Eventually, Balakirev, César Cui, Modest Mussorgsky, Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov and Alexander Borodin became known as the moguchaya kuchka, translated into English as the "Mighty Handful" or "The Five".[58] Rubinstein criticized their emphasis on amateur efforts in musical composition; Balakirev and later Mussorgsky attacked Rubinstein for his musical conservatism and his belief in professional music training.[59] Tchaikovsky and his fellow conservatory students were caught in the middle.[60]

While ambivalent about much of The Five's music, Tchaikovsky remained on friendly terms with most of its members.[61] In 1869, he and Balakirev worked together on what became Tchaikovsky's first recognized masterpiece, the fantasy-overture Romeo and Juliet, a work which The Five wholeheartedly embraced.[62] The group also welcomed his Second Symphony, subtitled the Little Russian.[63] Despite their support, Tchaikovsky made considerable efforts to ensure his musical independence from the group as well as from the conservative faction at the Saint Petersburg Conservatory.[64]

Growing fame; budding opera composer

The infrequency of Tchaikovsky's musical successes, won with tremendous effort, exacerbated his lifelong sensitivity to criticism. Nikolai Rubinstein's private fits of rage critiquing his music, such as attacking the First Piano Concerto, did not help matters.[65] His popularity grew, however, as several first-rate artists became willing to perform his compositions. Hans von Bülow premiered the First Piano Concerto and championed other Tchaikovsky works both as pianist and conductor.[66] Other artists included Adele aus der Ohe, Max Erdmannsdörfer, Eduard Nápravník and Sergei Taneyev.

Another factor that helped Tchaikovsky's music become popular was a shift in attitude among Russian audiences. Whereas they had previously been satisfied with flashy virtuoso performances of technically demanding but musically lightweight works, they gradually began listening with increasing appreciation of the composition itself. Tchaikovsky's works were performed frequently, with few delays between their composition and first performances; the publication from 1867 onward of his songs and great piano music for the home market also helped boost the composer's popularity.[67]

During the late 1860s, Tchaikovsky began to compose operas. His first, The Voyevoda, based on a play by Alexander Ostrovsky, premiered in 1869. The composer became dissatisfied with it, however, and, having re-used parts of it in later works, destroyed the manuscript. Undina followed in 1870. Only excerpts were performed and it, too, was destroyed.[68] Between these projects, Tchaikovsky started to compose an opera called Mandragora, to a libretto by Sergei Rachinskii; the only music he completed was a short chorus of Flowers and Insects.[69]

The first Tchaikovsky opera to survive intact, The Oprichnik, premiered in 1874. During its composition, he lost Ostrovsky's part-finished libretto. Tchaikovsky, too embarrassed to ask for another copy, decided to write the libretto himself, modelling his dramatic technique on that of Eugène Scribe. Cui wrote a "characteristically savage press attack" on the opera. Mussorgsky, writing to Vladimir Stasov, disapproved of the opera as pandering to the public. Nevertheless, The Oprichnik continues to be performed from time to time in Russia.[68]

The last of the early operas, Vakula the Smith (Op. 14), was composed in the second half of 1874. The libretto, based on Gogol's Christmas Eve, was to have been set to music by Alexander Serov. With Serov's death, the libretto was opened to a competition with a guarantee that the winning entry would be premiered by the Imperial Mariinsky Theatre. Tchaikovsky was declared the winner, but at the 1876 premiere, the opera enjoyed only a lukewarm reception.[70] After Tchaikovsky's death, Rimsky-Korsakov wrote the opera Christmas Eve, based on the same story.[71]

Other works of this period include the Variations on a Rococo Theme for cello and orchestra, the Third and Fourth Symphonies, the ballet Swan Lake, and the opera Eugene Onegin.

Personal life

Discussion of Tchaikovsky's personal life, especially his sexuality, has perhaps been the most extensive of any composer in the 19th century and certainly of any Russian composer of his time.[72] It has also at times caused considerable confusion, from Soviet efforts to expunge all references to same-sex attraction and portray him as a heterosexual, to efforts at analysis by Western biographers.[73]

Biographers have generally agreed that Tchaikovsky was homosexual.[74] He sought the company of other men in his circle for extended periods, "associating openly and establishing professional connections with them."[65] His first love was reportedly Sergey Kireyev, a younger fellow student at the Imperial School of Jurisprudence. According to Modest Tchaikovsky, this was Pyotr Ilyich's "strongest, longest and purest love." The degree to which the composer might have felt comfortable with his sexual desires has, however, remained open to debate. It is still unknown whether Tchaikovsky, according to musicologist and biographer David Brown, "felt tainted within himself, defiled by something from which he finally realized he could never escape"[75] or whether, according to Alexander Poznansky, he experienced "no unbearable guilt" over his sexual desires[65] and "eventually came to see his sexual peculiarities as an insurmountable and even natural part of his personality ... without experiencing any serious psychological damage."[76]

Relevant portions of his brother Modest's autobiography, where he tells of the composer's same-sex attraction, have been published, as have letters previously suppressed by Soviet censors in which Tchaikovsky openly writes of it.[77] Such censorship has persisted in the Russian government, resulting in many officials, including the former culture minister Vladimir Medinsky, denying his homosexuality outright.[78] Passages in Tchaikovsky's letters which reveal his homosexual desires have been censored in Russia. In one such passage he said of a homosexual acquaintance: "Petashenka used to drop by with the criminal intention of observing the Cadet Corps, which is right opposite our windows, but I've been trying to discourage these compromising visits—and with some success." In another one he wrote: "After our walk, I offered him some money, which was refused. He does it for the love of art and adores men with beards."[79]

Tchaikovsky lived as a bachelor for most of his life. In 1868, he met Belgian soprano Désirée Artôt with whom he considered marriage,[80] but, owing to various circumstances, the relationship ended.[81] Tchaikovsky later claimed she was the only woman he ever loved.[82] In 1877, at the age of 37, he wed a former student, Antonina Miliukova.[83] The marriage was a disaster. Mismatched psychologically and sexually,[84] the couple lived together for only two and a half months before Tchaikovsky left, overwrought emotionally and suffering from acute writer's block.[85] Tchaikovsky's family remained supportive of him during this crisis and throughout his life.[86] Tchaikovsky's marital debacle may have forced him to face the full truth about his sexuality; he never blamed Antonina for the failure of their marriage.[87]

He was also aided by Nadezhda von Meck, the widow of a railway magnate, who had begun contact with him not long before the marriage. As well as an important friend and emotional support,[88] she became his patroness for the next 13 years, which allowed him to focus exclusively on composition.[89] While Tchaikovsky called her his "best friend" they agreed to never meet under any circumstances.

Years of wandering

Tchaikovsky remained abroad for a year after the disintegration of his marriage. During this time, he completed Eugene Onegin, orchestrated his Fourth Symphony, and composed the Violin Concerto.[90] He returned briefly to the Moscow Conservatory in the autumn of 1879.[91][n 9] For the next few years, assured of a regular income from von Meck, he traveled incessantly throughout Europe and rural Russia, mainly alone, and avoided social contact whenever possible.[92]

During this time, Tchaikovsky's foreign reputation grew and a positive reassessment of his music also took place in Russia, thanks in part to Russian novelist Fyodor Dostoevsky's call for "universal unity" with the West at the unveiling of the Pushkin Monument in Moscow in 1880. Before Dostoevsky's speech, Tchaikovsky's music had been considered "overly dependent on the West". As Dostoevsky's message spread throughout Russia, this stigma toward Tchaikovsky's music evaporated.[93] The unprecedented acclaim for him even drew a cult following among the young intelligentsia of Saint Petersburg, including Alexandre Benois, Léon Bakst and Sergei Diaghilev.[94]

Two musical works from this period stand out. With the Cathedral of Christ the Saviour nearing completion in Moscow in 1880, the 25th anniversary of the coronation of Alexander II in 1881,[n 10] and the 1882 Moscow Arts and Industry Exhibition in the planning stage, Nikolai Rubinstein suggested that Tchaikovsky compose a grand commemorative piece. Tchaikovsky agreed and finished it within six weeks. He wrote to Nadezhda von Meck that this piece, the 1812 Overture, would be "very loud and noisy, but I wrote it with no warm feeling of love, and therefore there will probably be no artistic merits in it".[95] He also warned conductor Eduard Nápravník that "I shan't be at all surprised and offended if you find that it is in a style unsuitable for symphony concerts".[95] Nevertheless, the overture became, for many, "the piece by Tchaikovsky they know best",[96] particularly well-known for the use of cannon in the scores.[97]

On 23 March 1881, Nikolai Rubinstein died in Paris. That December, Tchaikovsky started work on his Piano Trio in A minor, "dedicated to the memory of a great artist".[98] First performed privately at the Moscow Conservatory on the first anniversary of Rubinstein's death, the piece became extremely popular during the composer's lifetime; in November 1893, it would become Tchaikovsky's own elegy at memorial concerts in Moscow and St. Petersburg.[99][n 11]

Return to Russia

In 1884, Tchaikovsky began to shed his unsociability and restlessness. That March, Emperor Alexander III conferred upon him the Order of Saint Vladimir (fourth class), which included a title of hereditary nobility[100] and a personal audience with the Tsar.[101] This was seen as a seal of official approval which advanced Tchaikovsky's social standing[100] and might have been cemented in the composer's mind by the success of his Orchestral Suite No. 3 at its January 1885 premiere in Saint Petersburg.[102]

In 1885, Alexander III requested a new production of Eugene Onegin at the Bolshoi Kamenny Theatre in Saint Petersburg.[n 12] By having the opera staged there and not at the Mariinsky Theatre, he served notice that Tchaikovsky's music was replacing Italian opera as the official imperial art. In addition, at the instigation of Ivan Vsevolozhsky, Director of the Imperial Theaters and a patron of the composer, Tchaikovsky was awarded a lifetime annual pension of 3,000 rubles from the Tsar. This made him the premier court composer, in practice if not in actual title.[103]

Despite Tchaikovsky's disdain for public life, he now participated in it as part of his increasing celebrity and out of a duty he felt to promote Russian music. He helped support his former pupil Sergei Taneyev, who was now director of Moscow Conservatory, by attending student examinations and negotiating the sometimes sensitive relations among various members of the staff. He served as director of the Moscow branch of the Russian Musical Society during the 1889–1890 season. In this post, he invited many international celebrities to conduct, including Johannes Brahms, Antonín Dvořák and Jules Massenet.[101]

During this period, Tchaikovsky also began promoting Russian music as a conductor,[101] In January 1887, he substituted, on short notice, at the Bolshoi Theater in Moscow for performances of his opera Cherevichki.[104] Within a year, he was in considerable demand throughout Europe and Russia. These appearances helped him overcome life-long stage fright and boosted his self-assurance.[105] In 1888, Tchaikovsky led the premiere of his Fifth Symphony in Saint Petersburg, repeating the work a week later with the first performance of his tone poem Hamlet. Although critics proved hostile, with César Cui calling the symphony "routine" and "meretricious", both works were received with extreme enthusiasm by audiences and Tchaikovsky, undeterred, continued to conduct the symphony in Russia and Europe.[106] Conducting brought him to the United States in 1891, where he led the New York Music Society's orchestra in his Festival Coronation March at the inaugural concert of Carnegie Hall.[107]

Belyayev circle and growing reputation

.gif)

In November 1887, Tchaikovsky arrived at Saint Petersburg in time to hear several of the Russian Symphony Concerts, devoted exclusively to the music of Russian composers. One included the first complete performance of his revised First Symphony; another featured the final version of Third Symphony of Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov, with whose circle Tchaikovsky was already in touch.[108]

Rimsky-Korsakov, with Alexander Glazunov, Anatoly Lyadov and several other nationalistically minded composers and musicians, had formed a group known as the Belyayev circle, named after a merchant and amateur musician who became an influential music patron and publisher.[109] Tchaikovsky spent much time in this circle, becoming far more at ease with them than he had been with the 'Five' and increasingly confident in showcasing his music alongside theirs.[110] This relationship lasted until Tchaikovsky's death.[111][112]

In 1892, Tchaikovsky was voted a member of the Académie des Beaux-Arts in France, only the second Russian subject to be so honored (the first was sculptor Mark Antokolsky).[113] The following year, the University of Cambridge in England awarded Tchaikovsky an honorary Doctor of Music degree.[114]

Death

On 16/28 October 1893, Tchaikovsky conducted the premiere of his Sixth Symphony,[115] the Pathétique, in Saint Petersburg. Nine days later, Tchaikovsky died there, aged 53. He was interred in Tikhvin Cemetery at the Alexander Nevsky Monastery, near the graves of fellow-composers Alexander Borodin, Mikhail Glinka, and Modest Mussorgsky; later, Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov and Mily Balakirev were also buried nearby.[116]

While Tchaikovsky's death has traditionally been attributed to cholera from drinking unboiled water at a local restaurant,[117] there has been much speculation that his death was suicide.[118] In the New Grove Dictionary of Music, Roland John Wiley wrote that "The polemics over [Tchaikovsky's] death have reached an impasse ... Rumors attached to the famous die hard ... As for illness, problems of evidence offer little hope of satisfactory resolution: the state of diagnosis; the confusion of witnesses; disregard of long-term effects of smoking and alcohol. We do not know how Tchaikovsky died. We may never find out".[119]

Music

Creative range

Tchaikovsky displayed a wide stylistic and emotional range, from light salon works to grand symphonies. Some of his works, such as the Variations on a Rococo Theme, employ a "Classical" form reminiscent of 18th-century composers such as Mozart (his favorite composer). Other compositions, such as his Little Russian symphony and his opera Vakula the Smith, flirt with musical practices more akin to those of the 'Five', especially in their use of folk song.[120] Other works, such as Tchaikovsky's last three symphonies, employ a personal musical idiom that facilitated intense emotional expression.[121]

Melody

American music critic and journalist Harold C. Schonberg wrote of Tchaikovsky's "sweet, inexhaustible, supersensuous fund of melody", a feature that has ensured his music's continued success with audiences.[122] Tchaikovsky's complete range of melodic styles was as wide as that of his compositions. Sometimes he used Western-style melodies, sometimes original melodies written in the style of Russian folk song; sometimes he used actual folk songs.[120] According to The New Grove, Tchaikovsky's melodic gift could also become his worst enemy in two ways.

The first challenge arose from his ethnic heritage. Unlike Western themes, the melodies that Russian composers wrote tended to be self-contained: they functioned with a mindset of stasis and repetition rather than one of progress and ongoing development. On a technical level, it made modulating to a new key to introduce a contrasting second theme exceedingly difficult, as this was literally a foreign concept that did not exist in Russian music.[123]

The second way melody worked against Tchaikovsky was a challenge that he shared with the majority of Romantic-age composers. They did not write in the regular, symmetrical melodic shapes that worked well with sonata form, such as those favored by Classical composers such as Haydn, Mozart or Beethoven; rather, the themes favored by Romantics were complete and independent in themselves.[124] This completeness hindered their use as structural elements in combination with one another. This challenge was why the Romantics "were never natural symphonists".[125] All a composer like Tchaikovsky could do with them was to essentially repeat them, even when he modified them to generate tension, maintain interest and satisfy listeners.[126]

Harmony

Harmony could be a potential trap for Tchaikovsky, according to Brown, since Russian creativity tended to focus on inertia and self-enclosed tableaux, while Western harmony worked against this to propel the music onward and, on a larger scale, shape it.[127] Modulation, the shifting from one key to another, was a driving principle in both harmony and sonata form, the primary Western large-scale musical structure since the middle of the 18th century. Modulation maintained harmonic interest over an extended time-scale, provided a clear contrast between musical themes and showed how those themes were related to each other.[128]

One point in Tchaikovsky's favor was "a flair for harmony" that "astonished" Rudolph Kündinger, Tchaikovsky's music tutor during his time at the School of Jurisprudence.[129] Added to what he learned at the Saint Petersburg Conservatory studies, this talent allowed Tchaikovsky to employ a varied range of harmony in his music, from the Western harmonic and textural practices of his first two string quartets to the use of the whole tone scale in the center of the finale of the Second Symphony, a practice more typically used by The Five.[120]

Rhythm

Rhythmically, Tchaikovsky sometimes experimented with unusual meters. More often, he used a firm, regular meter, a practice that served him well in dance music. At times, his rhythms became pronounced enough to become the main expressive agent of the music. They also became a means, found typically in Russian folk music, of simulating movement or progression in large-scale symphonic movements—a "synthetic propulsion", as Brown phrases it, which substituted for the momentum that would be created in strict sonata form by the interaction of melodic or motivic elements. This interaction generally does not take place in Russian music.[130] (For more on this, please see Repetition below.)

Structure

Tchaikovsky struggled with sonata form. Its principle of organic growth through the interplay of musical themes was alien to Russian practice.[123] The traditional argument that Tchaikovsky seemed unable to develop themes in this manner fails to consider this point; it also discounts the possibility that Tchaikovsky might have intended the development passages in his large-scale works to act as "enforced hiatuses" to build tension, rather than grow organically as smoothly progressive musical arguments.[131]

According to Brown and musicologists Hans Keller and Daniel Zhitomirsky, Tchaikovsky found his solution to large-scale structure while composing the Fourth Symphony. He essentially sidestepped thematic interaction and kept sonata form only as an "outline", as Zhitomirsky phrases it.[132] Within this outline, the focus centered on periodic alternation and juxtaposition. Tchaikovsky placed blocks of dissimilar tonal and thematic material alongside one another, with what Keller calls "new and violent contrasts" between musical themes, keys, and harmonies.[133] This process, according to Brown and Keller, builds momentum[134] and adds intense drama.[135] While the result, Warrack charges, is still "an ingenious episodic treatment of two tunes rather than a symphonic development of them" in the Germanic sense,[136] Brown counters that it took the listener of the period "through a succession of often highly charged sections which added up to a radically new kind of symphonic experience" (italics Brown), one that functioned not on the basis of summation, as Austro-German symphonies did, but on one of accumulation.[134]

Partly owing to the melodic and structural intricacies involved in this accumulation and partly due to the composer's nature, Tchaikovsky's music became intensely expressive.[137] This intensity was entirely new to Russian music and prompted some Russians to place Tchaikovsky's name alongside that of Dostoevsky.[138] German musicologist Hermann Kretzschmar credits Tchaikovsky in his later symphonies with offering "full images of life, developed freely, sometimes even dramatically, around psychological contrasts ... This music has the mark of the truly lived and felt experience".[139] Leon Botstein, in elaborating on this comment, suggests that listening to Tchaikovsky's music "became a psychological mirror connected to everyday experience, one that reflected on the dynamic nature of the listener's own emotional self". This active engagement with the music "opened for the listener a vista of emotional and psychological tension and an extremity of feeling that possessed relevance because it seemed reminiscent of one's own 'truly lived and felt experience' or one's search for intensity in a deeply personal sense".[140]

Repetition

As mentioned above, repetition was a natural part of Tchaikovsky's music, just as it is an integral part of Russian music.[141] His use of sequences within melodies (repeating a tune at a higher or lower pitch in the same voice)[142] could go on for extreme length.[120] The problem with repetition is that, over a period of time, the melody being repeated remains static, even when there is a surface level of rhythmic activity added to it.[143] Tchaikovsky kept the musical conversation flowing by treating melody, tonality, rhythm and sound color as one integrated unit, rather than as separate elements.[144]

By making subtle but noticeable changes in the rhythm or phrasing of a tune, modulating to another key, changing the melody itself or varying the instruments playing it, Tchaikovsky could keep a listener's interest from flagging. By extending the number of repetitions, he could increase the musical and dramatic tension of a passage, building "into an emotional experience of almost unbearable intensity", as Brown phrases it, controlling when the peak and release of that tension would take place.[145] Musicologist Martin Cooper calls this practice a subtle form of unifying a piece of music and adds that Tchaikovsky brought it to a high point of refinement.[146] (For more on this practice, see the next section.)

Orchestration

Like other late Romantic composers, Tchaikovsky relied heavily on orchestration for musical effects.[147] Tchaikovsky, however, became noted for the "sensual opulence" and "voluptuous timbrel virtuosity" of his orchestration.[148] Like Glinka, Tchaikovsky tended toward bright primary colors and sharply delineated contrasts of texture.[149] However, beginning with the Third Symphony, Tchaikovsky experimented with an increased range of timbres[150] Tchaikovsky's scoring was noted and admired by some of his peers. Rimsky-Korsakov regularly referred his students at the Saint Petersburg Conservatory to it and called it "devoid of all striving after effect, [to] give a healthy, beautiful sonority".[151] This sonority, musicologist Richard Taruskin pointed out, is essentially Germanic in effect. Tchaikovsky's expert use of having two or more instruments play a melody simultaneously (a practice called doubling) and his ear for uncanny combinations of instruments resulted in "a generalized orchestral sonority in which the individual timbres of the instruments, being thoroughly mixed, would vanish".[152]

Pastiche (Passé-ism)

In works like the "Serenade for Strings" and the Variations on a Rococo Theme, Tchaikovsky showed he was highly gifted at writing in a style of 18th-century European pastiche. In the ballet The Sleeping Beauty and the opera The Queen of Spades, Tchaikovsky graduated from imitation to full-scale evocation. This practice, which Alexandre Benois calls "passé-ism", lends an air of timelessness and immediacy, making the past seem as though it were the present.[153] On a practical level, Tchaikovsky was drawn to past styles because he felt he might find the solution to certain structural problems within them. His Rococo pastiches also may have offered escape into a musical world purer than his own, into which he felt himself irresistibly drawn. (In this sense, Tchaikovsky operated in the opposite manner to Igor Stravinsky, who turned to Neoclassicism partly as a form of compositional self-discovery.) Tchaikovsky's attraction to ballet might have allowed a similar refuge into a fairy-tale world, where he could freely write dance music within a tradition of French elegance.[154]

Antecedents and influences

Of Tchaikovsky's Western predecessors, Robert Schumann stands out as an influence in formal structure, harmonic practices and piano writing, according to Brown and musicologist Roland John Wiley.[155] Boris Asafyev comments that Schumann left his mark on Tchaikovsky not just as a formal influence but also as an example of musical dramaturgy and self-expression.[156] Leon Botstein claims the music of Franz Liszt and Richard Wagner also left their imprints on Tchaikovsky's orchestral style.[157][n 13] The late-Romantic trend for writing orchestral suites, begun by Franz Lachner, Jules Massenet, and Joachim Raff after the rediscovery of Bach's works in that genre, may have influenced Tchaikovsky to try his own hand at them.[158]

His teacher Anton Rubinstein's opera The Demon became a model for the final tableau of Eugene Onegin.[159] So did Léo Delibes' ballets Coppélia and Sylvia for The Sleeping Beauty[n 14] and Georges Bizet's opera Carmen (a work Tchaikovsky admired tremendously) for The Queen of Spades.[160] Otherwise, it was to composers of the past that Tchaikovsky turned—Beethoven, whose music he respected;[161] Mozart, whose music he loved;[161] Glinka, whose opera A Life for the Tsar made an indelible impression on him as a child and whose scoring he studied assiduously;[162] and Adolphe Adam, whose ballet Giselle was a favorite of his from his student days and whose score he consulted while working on The Sleeping Beauty.[163] Beethoven's string quartets may have influenced Tchaikovsky's attempts in that medium.[164] Other composers whose work interested Tchaikovsky included Hector Berlioz, Felix Mendelssohn, Giacomo Meyerbeer, Gioachino Rossini,[165] Giuseppe Verdi,[166] Vincenzo Bellini,[167] Carl Maria von Weber[168] and Henry Litolff.[169]

Aesthetic impact

Maes maintains that, regardless of what he was writing, Tchaikovsky's main concern was how his music impacted his listeners on an aesthetic level, at specific moments in the piece and on a cumulative level once the music had finished. What his listeners experienced on an emotional or visceral level became an end in itself.[170] Tchaikovsky's focus on pleasing his audience might be considered closer to that of Mendelssohn or Mozart. Considering that he lived and worked in what was probably the last 19th-century feudal nation, the statement is not actually that surprising.[171]

And yet, even when writing so-called 'programme' music, for example his Romeo and Juliet fantasy overture, he cast it in sonata form. His use of stylized 18th-century melodies and patriotic themes was geared toward the values of Russian aristocracy.[172] He was aided in this by Ivan Vsevolozhsky, who commissioned The Sleeping Beauty from Tchaikovsky and the libretto for The Queen of Spades from Modest with their use of 18th century settings stipulated firmly.[173][n 15] Tchaikovsky also used the polonaise frequently, the dance being a musical code for the Romanov dynasty and a symbol of Russian patriotism. Using it in the finale of a work could assure its success with Russian listeners.[174]

Reception

Dedicatees and collaborators

Tchaikovsky's relationship with collaborators was mixed. Like Nikolai Rubinstein with the First Piano Concerto, virtuoso and pedagogue Leopold Auer rejected the Violin Concerto initially but changed his mind; he played it to great public success and taught it to his students, who included Jascha Heifetz and Nathan Milstein.[175] Wilhelm Fitzenhagen "intervened considerably in shaping what he considered 'his' piece", the Variations on a Rococo Theme, according to music critic Michael Steinberg. Tchaikovsky was angered by Fitzenhagen's license but did nothing; the Rococo Variations were published with the cellist's amendments.[176][n 16]

His collaboration on the three ballets went better and in Marius Petipa, who worked with him on the last two, he might have found an advocate.[n 17] When The Sleeping Beauty was seen by its dancers as needlessly complicated, Petipa convinced them to put in the extra effort. Tchaikovsky compromised to make his music as practical as possible for the dancers and was accorded more creative freedom than ballet composers were usually accorded at the time. He responded with scores that minimized the rhythmic subtleties normally present in his work but were inventive and rich in melody, with more refined and imaginative orchestration than in the average ballet score.[177]

Critics

Critical reception to Tchaikovsky's music was varied but also improved over time. Even after 1880, some inside Russia held it suspect for not being nationalistic enough and thought Western European critics lauded it for exactly that reason.[178] There might have been a grain of truth in the latter, according to musicologist and conductor Leon Botstein, as German critics especially wrote of the "indeterminacy of [Tchaikovsky's] artistic character ... being truly at home in the non-Russian".[179] Of the foreign critics who did not care for his music, Eduard Hanslick lambasted the Violin Concerto as a musical composition "whose stink one can hear"[180] and William Forster Abtrop wrote of the Fifth Symphony, "The furious peroration sounds like nothing so much as a horde of demons struggling in a torrent of brandy, the music growing drunker and drunker. Pandemonium, delirium tremens, raving, and above all, noise worse confounded!"[181]

The division between Russian and Western critics remained through much of the 20th century but for a different reason. According to Brown and Wiley, the prevailing view of Western critics was that the same qualities in Tchaikovsky's music that appealed to audiences—its strong emotions, directness and eloquence and colorful orchestration—added up to compositional shallowness.[182] The music's use in popular and film music, Brown says, lowered its esteem in their eyes still further.[120] There was also the fact, pointed out earlier, that Tchaikovsky's music demanded active engagement from the listener and, as Botstein phrases it, "spoke to the listener's imaginative interior life, regardless of nationality". Conservative critics, he adds, may have felt threatened by the "violence and 'hysteria'" they detected and felt such emotive displays "attacked the boundaries of conventional aesthetic appreciation—the cultured reception of art as an act of formalist discernment—and the polite engagement of art as an act of amusement".[140]

There has also been the fact that the composer did not follow sonata form strictly, relying instead on juxtaposing blocks of tonalities and thematic groups. Maes states this point has been seen at times as a weakness rather than a sign of originality.[144] Even with what Schonberg termed "a professional reevaluation" of Tchaikovsky's work,[183] the practice of faulting Tchaikovsky for not following in the steps of the Viennese masters has not gone away entirely, while his intent of writing music that would please his audiences is also sometimes taken to task. In a 1992 article, New York Times critic Allan Kozinn writes, "It is Tchaikovsky's flexibility, after all, that has given us a sense of his variability.... Tchaikovsky was capable of turning out music—entertaining and widely beloved though it is—that seems superficial, manipulative and trivial when regarded in the context of the whole literature. The First Piano Concerto is a case in point. It makes a joyful noise, it swims in pretty tunes and its dramatic rhetoric allows (or even requires) a soloist to make a grand, swashbuckling impression. But it is entirely hollow".[184]

In the 21st century, however, critics are reacting more positively to Tchaikovsky's tunefulness, originality, and craftsmanship.[183] "Tchaikovsky is being viewed again as a composer of the first rank, writing music of depth, innovation and influence," according to cultural historian and author Joseph Horowitz.[185] Important in this reevaluation is a shift in attitude away from the disdain for overt emotionalism that marked half of the 20th century.[186] "We have acquired a different view of Romantic 'excess,'" Horowitz says. "Tchaikovsky is today more admired than deplored for his emotional frankness; if his music seems harried and insecure, so are we all".[185]

Public

Horowitz maintains that, while the standing of Tchaikovsky's music has fluctuated among critics, for the public, "it never went out of style, and his most popular works have yielded iconic sound-bytes [sic], such as the love theme from Romeo and Juliet".[185] Along with those tunes, Botstein adds, "Tchaikovsky appealed to audiences outside of Russia with an immediacy and directness that were startling even for music, an art form often associated with emotion".[187] Tchaikovsky's melodies, stated with eloquence and matched by his inventive use of harmony and orchestration, have always ensured audience appeal.[188] His popularity is considered secure, with his following in many countries, including the United States and the United Kingdom, second only to that of Beethoven.[119] His music has also been used frequently in popular music and film.[189]

Legacy

According to Wiley, Tchaikovsky was a pioneer in several ways. "Thanks in large part to Nadezhda von Meck", Wiley writes, "he became the first full-time professional Russian composer". This, Wiley adds, allowed him the time and freedom to consolidate the Western compositional practices he had learned at the Saint Petersburg Conservatory with Russian folk song and other native musical elements to fulfill his own expressive goals and forge an original, deeply personal style. He made an impact in not only absolute works such as the symphony but also program music and, as Wiley phrases it, "transformed Liszt's and Berlioz's achievements ... into matters of Shakespearean elevation and psychological import".[190] Wiley and Holden both note that Tchaikovsky did all this without a native school of composition upon which to fall back. They point out that only Glinka had preceded him in combining Russian and Western practices and his teachers in Saint Petersburg had been thoroughly Germanic in their musical outlook. He was, they write, for all intents and purposes alone in his artistic quest.[191]

Maes and Taruskin write that Tchaikovsky believed that his professionalism in combining skill and high standards in his musical works separated him from his contemporaries in The Five.[192] Maes adds that, like them, he wanted to produce music that reflected Russian national character but which did so to the highest European standards of quality.[193] Tchaikovsky, according to Maes, came along at a time when the nation itself was deeply divided as to what that character truly was. Like his country, Maes writes, it took him time to discover how to express his Russianness in a way that was true to himself and what he had learned. Because of his professionalism, Maes says, he worked hard at this goal and succeeded. The composer's friend, music critic Herman Laroche, wrote of The Sleeping Beauty that the score contained "an element deeper and more general than color, in the internal structure of the music, above all in the foundation of the element of melody. This basic element is undoubtedly Russian".[194]

Tchaikovsky was inspired to reach beyond Russia with his music, according to Maes and Taruskin.[195] His exposure to Western music, they write, encouraged him to think it belonged to not just Russia but also the world at large.[43] Volkov adds that this mindset made him think seriously about Russia's place in European musical culture—the first Russian composer to do so.[93] It steeled him to become the first Russian composer to acquaint foreign audiences personally with his own works, Warrack writes, as well as those of other Russian composers.[196] In his biography of Tchaikovsky, Anthony Holden recalls the dearth of Russian classical music before Tchaikovsky's birth, then places the composer's achievements into historical perspective: "Twenty years after Tchaikovsky's death, in 1913, Igor Stravinsky's The Rite of Spring erupted onto the musical scene, signaling Russia's arrival into 20th-century music. Between these two very different worlds, Tchaikovsky's music became the sole bridge".[197]

Tchaikovsky's voice

A recording was made in Moscow in January 1890, by Julius Block on behalf of Thomas Edison.[198] A transcript of the recording follows:

| Anton Rubinstein: | What a wonderful thing. | Какая прекрасная вещь ....хорошо... (in Russian) |

| Julius Block: | At last. | Наконец-то. |

| Lavrovskaya: | You're disgusting. How dare you call me crafty? | Пративный *** да как вы смеете называть меня коварной? |

| Vasily Safonov: | (sings) | |

| Pyotr Tchaikovsky: | This trill could be better. | Эта трель могла бы быть и лучше. |

| Lavrovskaya: | (sings) | |

| Tchaikovsky: | Blok is a good fellow, but Edison is even better. | Блок молодец, но у Эдисона ещё лучше! |

| Lavrovskaya: | (sings) A-o, a-o. | А-о, а-о. |

| Safonov: | Peter Jurgenson in Moscow. | Peter Jurgenson in Moskau. (in German) |

| Tchaikovsky: | Who's speaking now? It seems like Safonov's voice. | Кто сейчас говорит? Кажется голос Сафонова. |

| Safonov: | (whistles) |

According to musicologist Leonid Sabaneyev, Tchaikovsky was not comfortable with being recorded for posterity and tried to shy away from it. On an apparently separate visit from the one related above, Block asked the composer to play something on a piano or at least say something. Tchaikovsky refused. He told Block, "I am a bad pianist and my voice is raspy. Why should one eternalize it?"[199]

Notes

- Often anglicized as Peter Ilich Tchaikovsky; also standardized by the Library of Congress. His names are also transliterated as Piotr or Petr; Ilitsch or Il'ich; and Tschaikowski, Tschaikowsky, Chajkovskij, or Chaikovsky. He used to sign his name/was known as P. Tschaïkowsky/Pierre Tschaïkowsky in French (as in his afore-reproduced signature), and Peter Tschaikowsky in German, spellings also displayed on several of his scores' title pages in their first printed editions alongside or in place of his native name. The modern transliterations of Russian produce the following results for 'Пётр Ильич Чайковский' — ISO 9: Pëtr Ilʹič Čajkovskij, ALA-LC: Pëtr Ilʹich Chaĭkovskiĭ, BGN/PCGN: Pëtr Il’ich Chaykovskiy.[1]

- Петръ Ильичъ Чайковскій in Russian pre-revolutionary script.

- Russia was still using old style dates in the 19th century, rendering his lifespan as 25 April 1840 – 25 October 1893. Some sources in the article report dates as old style rather than new style.

- Tchaikovsky had four brothers (Nikolai, Ippolit, Anatoly and Modest), a sister (Alexandra) and a half-sister (Zinaida) from his father's first marriage (Holden, 6, 13; Warrack, Tchaikovsky, 18). Anatoly would later have a prominent legal career, while Modest became a dramatist, librettist, and translator (Poznansky, Eyes, 2).

- Her death affected him so much that he could not inform Fanny Dürbach until two years later (Brown, The Early Years, 47; Holde, 23; Warrack, 29). More than 25 years after his loss, Tchaikovsky wrote to his patroness, Nadezhda von Meck, "Every moment of that appalling day is as vivid to me as though it were yesterday" (As quoted in Holden, 23.)

- Tchaikovsky ascribed Rubinstein's coolness to a difference in musical temperaments. Rubinstein could have been jealous professionally of Tchaikovsky's greater impact as a composer. Homophobia might have been another factor (Poznansky, Eyes, 29).

- An exception to Rubinstein's antipathy was the Serenade for Strings, which he declared "Tchaikovsky's best piece" when he heard it in rehearsal. "At last this St. Petersburg pundit, who had growled with such consistent disapproval at Tchaikovsky's successive compositions, had found a work by his former pupil which he could endorse", according to Tchaikovsky biographer David Brown (Brown, The Years of Wandering, 121).

- His critique led Tchaikovsky to consider rescoring Schumann's symphonies, a project he never realized (Wiley, Tchaikovsky, 79).

- Rubinstein had actually been operating under the assumption that Tchaikovsky might leave from the onset of the composer's marital crisis and was prepared for it (Wiley, Tchaikovsky, 189–190). However, his meddling in the Tchaikovsky–von Meck relationship might have contributed to the composer's actual departure. Rubinstein's actions, which soured his relations with both Tchaikovsky and von Meck, included imploring von Meck in person to end Tchaikovsky's subsidy for the composer's own good (Brown, The Crisis Years, 250; Wiley, Tchaikovsky, 188–189). Rubinstein's actions, in turn, had been spurred by Tchaikovsky's withdrawal from the Russian delegation for the 1878 Paris World's Fair, a position for which Rubinstein had lobbied on the composer's behalf (Brown, The Crisis Years, 249–250; Wiley, Tchaikovsky, 180, 188–189). Rubinstein had been scheduled to conduct four concerts there; the first featured Tchaikovsky's First Piano Concerto (Wiley, Tchaikovsky, 190).

- Celebration of this anniversary did not take place as Alexander II was assassinated in March 1881.

- The piece also fulfilled a long-standing request by von Meck for such a work, to be performed by her then-house pianist, Claude Debussy (Brown, New Grove vol. 18, p. 620).

- Its only other production had been by students from the Conservatory.

- As proof of Wagner's influence, Botstein cites a letter from Tchaikovsky to Taneyev, in which the composer "readily admits the influence of the Nibelungen on Francesca da Rimini". This letter is quoted in Brown, The Crisis Years, 108.

- While it is sometimes thought these two ballets also influenced Tchaikovsky's work on Swan Lake, he had already composed that work before learning of them (Brown, The Crisis Years, 77).

- Vsevolozhsky originally intended the libretto for a now-unknown composer named Nikolai Klenovsky, not Tchaikovsky (Maes, 152).

- The composer's original has since been published but most cellists still perform Fitzenhagen's version (Campbell, 77).

- Tchaikovsky's work with Julius Reisinger on Swan Lake was evidently also successful, since it left him with no qualms about working with Petipa, but very little is written about it (Maes, 146).

References

- "Russian – BGN/PCGN transliteration system". transliteration.com. Retrieved 2 December 2020.

- "Tchaikovsky". Random House Webster's Unabridged Dictionary.

- John, Arit (24 August 2013). "Sorry, Russia, but Tchaikovsky Was Definitely Gay". The Atlantic. Retrieved 30 October 2021.

- According to longtime New York Times music critic Harold C. Schonberg.

- Holden, 4.

- "Tchaikovsky: A Life". tchaikovsky-research.net.

- "Pyotr Tchaikovsky, a Ukrainian by creative spirit". The Day. Kyiv.

- Kearney, Leslie (2014). Tchaikovsky and His World. Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-1-4008-6488-1.

- Brown, The Early Years, 19

- Poznansky, Eyes, 1

- Poznansky, Eyes, 1; Holden, 5.

- Wiley, Tchaikovsky, 6.

- Holden, 31.

- "Aleksandra Davydova". en.tchaikovsky-research.net.

- Holden, 43.

- Holden, 202.

- Brown, The Early Years, 22; Holden, 7.

- Holden, 7.

- Brown, The Early Years, 27; Holden, 6–8.

- Poznansky, Quest, 5.

- Brown, The Early Years, 25–26; Wiley, Tchaikovsky, 7.

- Brown, The Early Years, 31; Wiley, Tchaikovsky, 8.

- Maes, 33.

- Wiley, Tchaikovsky, 8.

- Holden, 14; Warrack, Tchaikovsky, 26.

- Holden, 20.

- Holden, 15; Poznansky, Quest, 11–12.

- Holden, 23.

- Holden, 23–24, 26; Poznansky, Quest, 32–37; Warrack, Tchaikovsky, 30.

- Holden, 24; Poznansky, Quest, 26

- As quoted in Holden, 25.

- Brown, The Early Years, 43.

- Holden, 24–25; Warrack, Tchaikovsky, 31.

- Poznansky, Eyes, 17.

- Holden, 25; Warrack, Tchaikovsky, 31.

- Brown, Man and Music, 14.

- Maes, 31.

- Maes, 35.

- Volkov, 71.

- Maes, 35; Warrack, Tchaikovsky, 36.

- Brown, The Early Years, 60.

- Brown, Man and Music, 20; Holden, 38–39; Warrack, Tchaikovsky, 36–38.

- Taruskin, Grove Opera, 4:663–664.

- Figes, xxxii; Volkov, 111–112.

- Hosking, 347.

- Poznansky, Eyes, 47–48; Rubinstein, 110.

- Brown, The Early Years, 76; Wiley, Tchaikovsky, 35.

- Brown, The Early Years, 100–101.

- Brown, New Grove vol. 18, p. 608.

- Brown, The Early Years, 82–83.

- Holden, 83; Warrack, Tchaikovsky, 61.

- Wiley, Tchaikovsky, 87.

- Wiley, Tchaikovsky, 79.

- As quoted in Wiley, Tchaikovsky, 95.

- Wiley, Tchaikovsky, 77.

- Figes, 178–181

- Maes, 8–9; Wiley, Tchaikovsky, 27.

- Garden, New Grove (2001), 8:913.

- Maes, 39.

- Maes, 42.

- Maes, 49.

- Brown, Man and Music, 49.

- Brown, The Early Years, 255.

- Holden, 51–52.

- Wiley, New Grove (2001), 25:147.

- Steinberg, Concerto, 474–476; Wiley, New Grove (2001), 25:161.

- Wiley, New Grove (2001), 25:153–154.

- Taruskin, 665.

- Holden, 75–76; Warrack, Tchaikovsky, 58–59.

- Brown, Viking Opera Guide, 1086.

- Maes, 171.

- Wiley, Tchaikovsky, xvi.

- Maes, 133–134; Wiley, Tchaikovsky, xvii.

- Poznansky, Quest, 32 et passim.

- Brown, The Early Years, 50.

- Poznansky, as quoted in Holden, 394.

- Poznansky, Eyes, 8, 24, 77, 82, 103–105, 165–168. Also see P. I. Chaikovskii. Al'manakh, vypusk 1, (Moscow, 1995).

- Walker, Shaun (18 September 2013). "Tchaikovsky was not gay, says Russian culture minister". The Guardian. Retrieved 21 April 2018.

- Alberge, Dalya (2 June 2018). "Tchaikovsky and the secret gay loves censors tried to hide". The Guardian.

- Brown, The Early Years, 156–157; Warrack, Tchaikovsky, 53.

- Brown, The Early Years, 156–158; Poznansky, Eyes, 88.

- "Artôt, Désirée (1835–1907)". Schubertiade music. Archived from the original on 24 June 2009. Retrieved 21 February 2009.

- Brown, The Crisis Years, 137–147; Polayansky, Quest, 207–208, 219–220; Wiley, Tchaikovsky, 147–150.

- Brown, The Crisis Years, 146–148; Poznansky, Quest, 234; Wiley, Tchaikovsky, 152.

- Brown, The Crisis Years, 157; Poznansky, Quest, 234; Wiley, Tchaikovsky, 155.

- Wiley, New Grove (2001), 25:147.

- Warrack, Tchaikovsky, 120.

- Holden, 159, 231–232.

- Brown, Man and Music, 171–172.

- Wiley, Tchaikovsky, 159, 170, 193.

- Brown, The Crisis Years, 297.

- Brown, Man and Music, 219.

- Volkov, 126.

- Volkov, 122–123.

- As quoted in Brown, The Years of Wandering, 119.

- Brown, Man and Music, 224.

- Aaron Green,"Tchaikovsky's 1812 Overture", thoughtco.com, 25 March 2017

- As quoted in Brown, The Years of Wandering, 151.

- Brown, The Years of Wandering, 151–152.

- Brown, New Grove vol. 18, p. 621; Holden, 233.

- Wiley, New Grove (2001), 25:162.

- Brown, Man and Music, 275.

- Maes, 140; Taruskin, Grove Opera, 4:664.

- Holden, 261; Warrack, Tchaikovsky, 197.

- Holden, 266; Warrack, Tchaikovsky, 232.

- Holden, 272–273.

- Brown, The Final Years, 319–320.

- Brown, The Final Years, 90–91.

- Maes, 173

- Brown, The Final Years, 92.

- Poznansky, Quest, 564.

- Rimsky-Korsakov, 308.

- Poznansky, Quest, 548–549.

- Warrack, Tchaikovsky, 264.

- "Symphony No. 6". tchaikovsky-research.net.

- Brown, The Final Years, 487.

- Brown, Man and Music, 430–432; Holden, 371; Warrack, Tchaikovsky, 269–270.

- Brown, Man and Music, 431–435; Holden, 373–400.

- Wiley, New Grove (2001), 25:169.

- Brown, New Grove vol. 18, p. 628.

- Brown, New Grove vol. 18, p. 606.

- Schonberg, 366.

- Brown, The Final Years, 424.

- Cooper, 26.

- Cooper, 24.

- Warrack, Symphonies, 8–9.

- Brown, The Final Years, 422, 432–434.

- Roberts, New Grove (1980), 12:454.

- As quoted in Polyansky, Eyes, 18.

- Brown, New Grove vol. 18, p. 628; Final Years, 424.

- Zajaczkowski, 25

- Zhitomirsky, 102.

- Brown, The Final Years, 426; Keller, 347.

- Brown, The Final Years, 426.

- Keller, 346–47.

- Warrack, Symphonies, 11.

- Brown, New Grove vol. 18, p. 628; Keller, 346–347; Maes, 161.

- Volkov, 115

- As quoted in Botstein, 101.

- Botstein, 101.

- Warrack, Symphonies, 9. Also see Brown, The Final Years, 422–423.

- Benward & Saker, 111–112.

- Brown, The Final Years, 423–424; Warrack, Symphonies, 9.

- Maes, 161.

- Brown, New Grove vol. 18, p. 628. Also see Bostrick, 105.

- Cooper, 32.

- Holoman, New Grove (2001), 12:413.

- Maes, 73; Taruskin, Grove Opera, 4:669.

- Brown, New Grovevol. 18, p. 628; Hopkins, New Grove (1980), 13:698.

- Maes, 78.

- As quoted in Taruskin, Stravinsky, 206.

- Taruskin, Stravinsky, 206

- Volkov, 124.

- Brown, New Grove vol. 18, pp. 613, 615.

- Brown, New Grove vol. 18, pp. 613, 620; Wiley, Tchaikovsky, 58.

- Asafyev, 13–14.

- Bostein, 103.

- Fuller, New Grove (2001), 24:681–662; Maes, 155.

- Taruskin, Grove Opera, 4:664.

- Brown, The Final Years, 189; Maes, 131, 138, 152.

- Wiley, Tchaikovsky, 293–294.

- Brown, The Early Years, 34, 97.

- Brown, The Early Years, 39, 52; Brown, The Final Years, 187.

- Wiley, New Grove (2001), 25:149.

- "Gioachino Rossini". tchaikovsky-research.net.

- "Giuseppe Verdi". tchaikovsky-research.net.

- "Vincenzo Bellini". tchaikovsky-research.net.

- "Carl Maria von Weber". tchaikovsky-research.net.

- Brown, The Early Years, 72.

- Maes, 138.

- Figes, 274; Maes, 139–141.

- Maes, 137.

- Maes, 146, 152.

- Figes, 274; Maes, 78–79, 137.

- Steinberg, Concerto, 486

- Brown, The Crisis Years, 122.

- Maes, 145–148.

- Botstein, 99.

- As quoted in Botstein, 100.

- Hanslick, Eduard, Music Criticisms 1850–1900, ed. and trans. Henry Pleasants (Baltimore: Penguin Books, 1963). As quoted in Steinberg, Concerto, 487.

- Boston Evening Transcript, 23 October 1892. As quoted in Steinberg, Symphony, 631

- Brown, New Grove vol. 18, p. 628; Wiley, New Grove (2001), 25:169.

- Schonberg, 367.

- Kozinn

- Druckenbrod

- Wiley, New Grove (2001), 25:169.

- Botstein, 100.

- Brown, New Grove vol. 18, pp. 606–607, 628.

- Steinberg, The Symphony, 611.

- Wiley, New Grove (2001), 25:144.

- Holden, xxi; Wiley, New Grove (2001), 25:144.

- Maes, 73; Taruskin, Grove Opera, 4:663.

- Maes, 73.

- As quoted in Maes, 166.

- Maes, 73; Taruskin, Grove Opera, 664.

- Warrack, Tchaikovsky, 209.

- Holden, xxi.

- website

- As quoted in Poznansky, Eyes, 216.

Sources

- Asafyev, Boris (1947). "The Great Russian Composer". Russian Symphony: Thoughts About Tchaikovsky. New York: Philosophical Library. OCLC 385806.

- Benward, Bruce; Saker, Marilyn (200). Music: In Theory and Practice, Vol. 1 (Seventh ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill. ISBN 978-0-07-294262-0.

- Botstein, Leon (1998). "Music as the Language of Psychological Realm". In Kearney, Leslie (ed.). Tchaikovsky and His World. Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-00429-7.

- Brown, David (1980). "'Glinka, Mikhail Ivanovich' and 'Tchaikovsky, Pyotr Ilyich'". In Stanley Sadie (ed.). The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians (20 volumes). London: MacMillan. ISBN 978-0-333-23111-1.

- Brown, David (1978). Tchaikovsky: The Early Years, 1840–1874. New York: W. W. Norton. ISBN 978-0-393-07535-9.

- — (1983). Tchaikovsky: The Crisis Years, 1874–1878. New York: W. W. Norton. ISBN 978-0-393-01707-6.

- — (1986). Tchaikovsky: The Years of Wandering, 1878–1885. New York: W. W. Norton. ISBN 978-0-393-02311-4.

- — (1991). Tchaikovsky: The Final Years, 1885–1893. New York: W. W. Norton. ISBN 978-0-393-03099-0.

- Brown, David (1993). "Pyotr Tchaikovsky". In Amanda Holden; Nicholas Kenyon; Stephen Walsh (eds.). The Viking Opera Guide. London: Viking. ISBN 978-0-670-81292-9.

- Brown, David (2007). Tchaikovsky: The Man and His Music. New York: Pegasus. ISBN 978-0-571-23194-2.

- Cooper, Martin (1946). "The Symphonies". In Gerald Abraham (ed.). Music of Tchaikovsky. New York: W. W. Norton. OCLC 385829.

- Druckenbrod, Andrew (30 January 2011). "Festival to explore Tchaikovsky's changing reputation". Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. Retrieved 27 February 2012.

- Figes, Orlando (2002). Natasha's Dance: A Cultural History of Russia. New York: Metropolitan Books. ISBN 978-0-8050-5783-6.

- Holden, Anthony (1995). Tchaikovsky: A Biography. New York: Random House. ISBN 978-0-679-42006-4.

- Holoman, D. Kern, "Instrumentation and orchestration, 4: 19th century". In The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians, Second Edition (London: Macmillan, 2001), 29 vols., ed. Sadie, Stanley. ISBN 978-1-56159-239-5.

- Hopkins, G. W., "Orchestration, 4: 19th century". In The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians (London: MacMillan, 1980), 20 vols., ed. Sadie, Stanley. ISBN 978-0-333-23111-1.

- Hosking, Geoffrey, Russia and the Russians: A History (Cambridge, Massachusetts: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 2001). ISBN 978-0-674-00473-3.

- Kozinn, Allan, "Critic's Notebook; Defending Tchaikovsky, With Gravity and With Froth". In The New York Times, 18 July 1992. Retrieved 27 February 2012.

- Maes, Francis, tr. Arnold J. Pomerans and Erica Pomerans, A History of Russian Music: From Kamarinskaya to Babi Yar (Berkeley, Los Angeles and London: University of California Press, 2002). ISBN 978-0-520-21815-4.

- Poznansky, Alexander, Tchaikovsky: The Quest for the Inner Man (New York: Schirmer Books, 1991). ISBN 978-0-02-871885-9.

- Poznansky, Alexander, Tchaikovsky Through Others' Eyes. (Bloomington: Indiana Univ. Press, 1999). ISBN 978-0-253-33545-6.

- Roberts, David, "Modulation (i)". In The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians (London: MacMillan, 1980), 20 vols., ed. Sadie, Stanley. ISBN 978-0-333-23111-1.

- Rubinstein, Anton, tr. Aline Delano, Autobiography of Anton Rubinstein: 1829–1889 (New York: Little, Brown & Co., 1890). Library of Congress Control Number LCCN 06-4844.

- Schonberg, Harold C. Lives of the Great Composers (New York: W. W. Norton, 3rd ed. 1997). ISBN 978-0-393-03857-6.

- Steinberg, Michael, The Symphony (New York and Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1995).

- Steinberg, Michael, The Concerto (New York and Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1998).

- Taruskin, Richard, "Tchaikovsky, Pyotr Il'yich", The New Grove Dictionary of Opera (London and New York: Macmillan, 1992), 4 vols, ed. Sadie, Stanley. ISBN 978-0-333-48552-1.

- Taruskin, Richard, Stravinsky and the Russian Traditions, Volume One (Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press, 1996) ISBN 978-0-520-29348-9

- Volkov, Solomon, Romanov Riches: Russian Writers and Artists Under the Tsars (New York: Alfred A. Knopf House, 2011), tr. Bouis, Antonina W. ISBN 978-0-307-27063-4.

- Warrack, John, Tchaikovsky Symphonies and Concertos (Seattle: University of Washington Press, 1969). LCCN 78-105437.

- Warrack, John, Tchaikovsky (New York: Charles Scribner's Sons, 1973). ISBN 978-0-684-13558-8.

- Wiley, Roland John, "Tchaikovsky, Pyotr Ilyich". In The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians, Second Edition (London: Macmillan, 2001), 29 vols., ed. Sadie, Stanley. ISBN 978-1-56159-239-5.

- Wiley, Roland John, The Master Musicians: Tchaikovsky (Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press, 2009). ISBN 978-0-19-536892-5.

- Zhitomirsky, Daniel, "Symphonies". In Russian Symphony: Thoughts About Tchaikovsky (New York: Philosophical Library, 1947). OCLC 385806.

- Zajaczkowski, Henry, Tchaikovsky's Musical Style (Ann Arbor and London: UMI Research Press, 1987). ISBN 978-0-8357-1806-6.

Further reading

External links

- Free scores by Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky at the International Music Score Library Project (IMSLP)

- Tchaikovsky Research

- "Discovering Tchaikovsky". BBC Radio 3.

- Works by Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky at Internet Archive