Ivan Turgenev

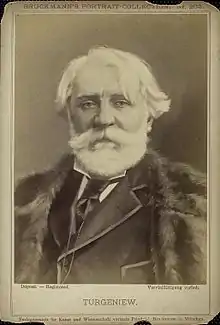

Ivan Sergeyevich Turgenev (English: /tʊərˈɡɛnjɛf, -ˈɡeɪn-/;[1] Russian: Ива́н Серге́евич Турге́нев[note 1], IPA: [ɪˈvan sʲɪrˈɡʲe(j)ɪvʲɪtɕ tʊrˈɡʲenʲɪf]; 9 November 1818 – 3 September 1883 (Old Style dates: 28 October 1818 – 22 August 1883) was a Russian novelist, short story writer, poet, playwright, translator and popularizer of Russian literature in the West.

Ivan Turgenev Ива́н Турге́нев | |

|---|---|

Turgenev, in 1874 | |

| Born | Ivan Sergeyevich Turgenev 9 November 1818 Oryol, Oryol Governorate, Russian Empire |

| Died | 3 September 1883 (aged 64) Bougival, Seine-et-Oise, France |

| Occupation | Writer, poet, translator |

| Genre | Novel, play, short story |

| Literary movement | Realism |

| Notable works |

|

| Children | 1 |

| Signature | |

| |

His first major publication, a short story collection entitled A Sportsman's Sketches (1852), was a milestone of Russian realism. His novel Fathers and Sons (1862) is regarded as one of the major works of 19th-century fiction.

Life

Ivan Sergeyevich Turgenev was born in Oryol (modern-day Oryol Oblast, Russia) to noble Russian parents Sergei Nikolaevich Turgenev (1793–1834), a colonel in the Russian cavalry who took part in the Patriotic War of 1812, and Varvara Petrovna Turgeneva (née Lutovinova; 1787–1850). His father belonged to an old, but impoverished Turgenev family of Tula aristocracy that traces its history to the 15th century when a Tatar Mirza Lev Turgen (Ivan Turgenev after baptizing) left the Golden Horde to serve Vasily II of Moscow.[2][3] Ivan's mother came from a wealthy noble Lutovinov house of the Oryol Governorate.[4] She spent an unhappy childhood under her tyrannical stepfather and left his house after her mother's death to live with her uncle. At the age of 26 she inherited a huge fortune from him.[5] In 1816, she married Turgenev.

Ivan and his brothers Nikolai and Sergei were raised by their mother, a very educated, but authoritarian woman, in the Spasskoye-Lutovinovo family estate that was granted to their ancestor Ivan Ivanovich Lutovinov by Ivan the Terrible.[4] Varvara Turgeneva later served as an inspiration for the landlady from Turgenev's Mumu. She surrounded her sons with foreign governesses; thus Ivan became fluent in French, German, and English. The family members used French in everyday life, even prayers were read in this language.[6] Their father spent little time with the family, and although he was not hostile toward them, his absence hurt Ivan's feelings (their relations are described in the autobiographical novel First Love). When he was four, the family made a trip through Germany and France. In 1827 the Turgenevs moved to Moscow to give their children a proper education.[5]

After the standard schooling for a son of a gentleman, Turgenev studied for one year at the University of Moscow and then moved to the University of Saint Petersburg[7] from 1834 to 1837, focusing on Classics, Russian literature, and philology. During that time his father died from kidney stone disease, followed by his younger brother Sergei who died from epilepsy.[5] From 1838 until 1841 he studied philosophy, particularly Hegel, and history at the University of Berlin. He returned to Saint Petersburg to complete his master's examination.

Turgenev was impressed with German society and returned home believing that Russia could best improve itself by incorporating ideas from the Age of Enlightenment. Like many of his educated contemporaries, he was particularly opposed to serfdom. In 1841, Turgenev started his career in the Russian civil service and spent two years working for the Ministry of Interior (1843–1845).

When Turgenev was a child, a family serf had read to him verses from the Rossiad of Mikhail Kheraskov, a celebrated poet of the 18th century. Turgenev's early attempts in literature, poems, and sketches gave indications of genius and were favorably spoken of by Vissarion Belinsky, then the leading Russian literary critic. During the latter part of his life, Turgenev did not reside much in Russia: he lived either at Baden-Baden or Paris, often in proximity to the family of the celebrated opera singer Pauline Viardot,[7] with whom he had a lifelong affair.

Turgenev never married, but he had some affairs with his family's serfs, one of which resulted in the birth of his illegitimate daughter, Paulinette. He was tall and broad-shouldered, but was timid, restrained, and soft-spoken. When Turgenev was 19, while traveling on a steamboat in Germany, the boat caught fire. According to rumours by Turgenev's enemies, he reacted in a cowardly manner. He denied such accounts, but these rumours circulated in Russia and followed him for his entire career, providing the basis for his story "A Fire at Sea".[8] His closest literary friend was Gustave Flaubert, with whom he shared similar social and aesthetic ideas. Both rejected extremist right and left political views, and carried a nonjudgmental, although rather pessimistic, view of the world. His relations with Leo Tolstoy and Fyodor Dostoyevsky were often strained, as the two were, for various reasons, dismayed by Turgenev's seeming preference for Western Europe.

Turgenev, unlike Tolstoy and Dostoyevsky, lacked religious motives in his writings, representing the more social aspect to the reform movement. He was considered to be an agnostic.[9] Tolstoy, more than Dostoyevsky, at first anyway, rather despised Turgenev. While traveling together in Paris, Tolstoy wrote in his diary, "Turgenev is a bore." His rocky friendship with Tolstoy in 1861 wrought such animosity that Tolstoy challenged Turgenev to a duel, afterwards apologizing. The two did not speak for 17 years, but never broke family ties. Dostoyevsky parodies Turgenev in his novel The Devils (1872) through the character of the vain novelist Karmazinov, who is anxious to ingratiate himself with the radical youth. However, in 1880, Dostoyevsky's speech at the unveiling of the Pushkin monument brought about a reconciliation of sorts with Turgenev, who, like many in the audience, was moved to tears by his rival's eloquent tribute to the Russian spirit.

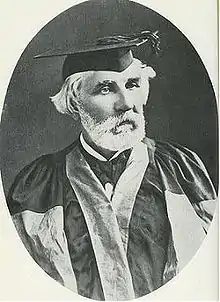

Turgenev occasionally visited England, and in 1879 the honorary degree of Doctor of Civil Law was conferred upon him by the University of Oxford.[7]

Turgenev's health declined during his later years. In January 1883, an aggressive malignant tumor (liposarcoma) was removed from his suprapubic region, but by then the tumor had metastasized in his upper spinal cord, causing him intense pain during the final months of his life. On 3 September 1883, Turgenev died of a spinal abscess, a complication of the metastatic liposarcoma, in his house at Bougival near Paris. His remains were taken to Russia and buried in Volkovo Cemetery in St. Petersburg.[10] On his death bed he pleaded with Tolstoy: "My friend, return to literature!" After this Tolstoy wrote such works as The Death of Ivan Ilyich and The Kreutzer Sonata.

Ivan Turgenev's brain was found to be one of the largest on record for neurologically typical individuals, weighing 2012 grams.[11]

Work

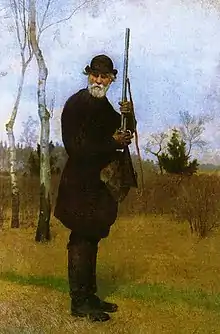

Turgenev first made his name with A Sportsman's Sketches (Записки охотника), also known as Sketches from a Hunter's Album or Notes of a Hunter, a collection of short stories, based on his observations of peasant life and nature, while hunting in the forests around his mother's estate of Spasskoye. Most of the stories were published in a single volume in 1852, with others being added in later editions. The book is credited with having influenced public opinion in favour of the abolition of serfdom in 1861. Turgenev himself considered the book to be his most important contribution to Russian literature; it is reported that Pravda,[12] and Tolstoy, among others, agreed wholeheartedly, adding that Turgenev's evocations of nature in these stories were unsurpassed.[13] One of the stories in A Sportsman's Sketches, known as "Bezhin Lea" or "Byezhin Prairie", was later to become the basis for the controversial film Bezhin Meadow (1937), directed by Sergei Eisenstein.

In 1852, when his first major novels of Russian society were still to come, Turgenev wrote an obituary for Nikolai Gogol, intended for publication in the Saint Petersburg Gazette. The key passage reads: "Gogol is dead!... What Russian heart is not shaken by those three words?... He is gone, that man whom we now have the right (the bitter right, given to us by death) to call great." The censor of Saint Petersburg did not approve of this and banned publication, but the Moscow censor allowed it to be published in a newspaper in that city. The censor was dismissed; but Turgenev was held responsible for the incident, imprisoned for a month, and then exiled to his country estate for nearly two years. It was during this time that Turgenev wrote his short story Mumu ("Муму") in 1854. The story tells a tale of a deaf and mute peasant who is forced to drown the only thing in the world which brings him happiness, his dog Mumu. Like his A Sportsman's Sketches (Записки охотника), this work takes aim at the cruelties of a serf society. This work was later applauded by John Galsworthy who claimed, "no more stirring protest against tyrannical cruelty was ever penned in terms of art."

While he was still in Russia in the early 1850s, Turgenev wrote several novellas (povesti in Russian): The Diary of a Superfluous Man ("Дневник лишнего человека"), Faust ("Фауст"), The Lull ("Затишье"), expressing the anxieties and hopes of Russians of his generation.

In the 1840s and early 1850s, during the rule of Tsar Nicholas I, the political climate in Russia was stifling for many writers. This is evident in the despair and subsequent death of Gogol, and the oppression, persecution, and arrests of artists, scientists, and writers. During this time, thousands of Russian intellectuals, members of the intelligentsia, emigrated to Europe. Among them were Alexander Herzen and Turgenev himself, who moved to Western Europe in 1854, although this decision probably had more to do with his fateful love for Pauline Viardot than anything else.

The following years produced the novel Rudin ("Рудин"), the story of a man in his thirties who is unable to put his talents and idealism to any use in the Russia of Nicholas I. Rudin is also full of nostalgia for the idealistic student circles of the 1840s.

Following the thoughts of the influential critic Vissarion Belinsky, Turgenev abandoned Romantic idealism for a more realistic style. Belinsky defended sociological realism in literature; Turgenev portrayed him in Yakov Pasinkov (1855). During the period of 1853–62 Turgenev wrote some of his finest stories as well as the first four of his novels: Rudin ("Рудин") (1856), A Nest of the Gentry ("Дворянское гнездо") (1859), On the Eve ("Накануне") (1860) and Fathers and Sons ("Отцы и дети") (1862). Some themes involved in these works include the beauty of early love, failure to reach one's dreams, and frustrated love. Great influences on these works are derived from his love of Pauline and his experiences with his mother, who controlled over 500 serfs with the same strict demeanor in which she raised him.

In 1858 Turgenev wrote the novel A Nest of the Gentry ("Дворянское гнездо"), also full of nostalgia for the irretrievable past and of love for the Russian countryside. It contains one of his most memorable female characters, Liza, whom Dostoyevsky paid tribute to in his Pushkin speech of 1880, alongside Tatiana and Tolstoy's Natasha Rostova.

Alexander II ascended the Russian throne in 1855, and the political climate became more relaxed. In 1859, inspired by reports of positive social changes, Turgenev wrote the novel On the Eve ("Накануне") (published 1860), portraying the Bulgarian revolutionary Insarov.

The following year saw the publication of one of his finest novellas, First Love ("Первая любовь"), which was based on bitter-sweet childhood memories, and the delivery of his speech ("Hamlet and Don Quixote", at a public reading in Saint Petersburg) in aid of writers and scholars suffering hardship. The vision presented therein of man torn between the self-centered skepticism of Hamlet and the idealistic generosity of Don Quixote is one that can be said to pervade Turgenev's own works. It is worth noting that Dostoyevsky, who had just returned from exile in Siberia, was present at this speech, for eight years later he was to write The Idiot, a novel whose tragic hero, Prince Myshkin, resembles Don Quixote in many respects.[14] Turgenev, whose knowledge of Spanish, thanks to his contact with Pauline Viardot and her family, was good enough for him to have considered translating Cervantes's novel into Russian, played an important role in introducing this immortal figure of world literature into the Russian context.

.jpg.webp)

Fathers and Sons ("Отцы и дети"), Turgenev's most famous and enduring novel, appeared in 1862. Its leading character, Eugene Bazarov, considered the "first Bolshevik" in Russian literature, was in turn heralded and reviled as either a glorification or a parody of the 'new men' of the 1860s. The novel examined the conflict between the older generation, reluctant to accept reforms, and the nihilistic youth. In the central character, Bazarov, Turgenev drew a classical portrait of the mid-nineteenth-century nihilist. Fathers and Sons was set during the six-year period of social ferment, from Russia's defeat in the Crimean War to the Emancipation of the Serfs. Hostile reaction to Fathers and Sons ("Отцы и дети") prompted Turgenev's decision to leave Russia. As a consequence he also lost the majority of his readers. Many radical critics at the time (with the notable exception of Dimitri Pisarev) did not take Fathers and Sons seriously; and, after the relative critical failure of his masterpiece, Turgenev was disillusioned and started to write less.

Turgenev's next novel, Smoke ("Дым"), was published in 1867 and was again received less than enthusiastically in his native country, as well as triggering a quarrel with Dostoyevsky in Baden-Baden.

His last substantial work attempting to do justice to the problems of contemporary Russian society, Virgin Soil ("Новь"), was published in 1877.

Stories of a more personal nature, such as Torrents of Spring ("Вешние воды"), King Lear of the Steppes ("Степной король Лир"), and The Song of Triumphant Love ("Песнь торжествующей любви"), were also written in these autumnal years of his life. Other last works included the Poems in Prose and "Clara Milich" ("After Death"), which appeared in the journal European Messenger.[7]

| "The conscious use of art for ends extraneous to itself was detestable to him... He knew that the Russian reader wanted to be told what to believe and how to live, expected to be provided with clearly contrasted values, clearly distinguishable heroes and villains.... Turgenev remained cautious and skeptical; the reader is left in suspense, in a state of doubt: problems are raised, and for the most part left unanswered" – Isaiah Berlin, Lecture on Fathers and Children[15] |

Turgenev wrote on themes similar to those found in the works of Tolstoy and Dostoyevsky, but he did not approve of the religious and moral preoccupations that his two great contemporaries brought to their artistic creation. Turgenev was closer in temperament to his friends Gustave Flaubert and Theodor Storm, the North German poet and master of the novella form, who also often dwelt on memories of the past and evoked the beauty of nature.[16]

Legacy

Turgenev's artistic purity made him a favorite of like-minded novelists of the next generation, such as Henry James and Joseph Conrad, both of whom greatly preferred Turgenev to Tolstoy and Dostoyevsky. James, who wrote no fewer than five critical essays on Turgenev's work, claimed that "his merit of form is of the first order" (1873) and praised his "exquisite delicacy", which "makes too many of his rivals appear to hold us, in comparison, by violent means, and introduce us, in comparison, to vulgar things" (1896).[17] Vladimir Nabokov, notorious for his casual dismissal of many great writers, praised Turgenev's "plastic musical flowing prose", but criticized his "labored epilogues" and "banal handling of plots". Nabokov stated that Turgenev "is not a great writer, though a pleasant one", and ranked him fourth among nineteenth-century Russian prose writers, behind Tolstoy, Gogol, and Anton Chekhov, but ahead of Dostoyevsky.[18] His idealistic ideas about love, specifically the devotion a wife should show her husband, were cynically referred to by characters in Chekhov's "An Anonymous Story". Isaiah Berlin acclaimed Turgenev's commitment to humanism, pluralism, and gradual reform over violent revolution as representing the best aspects of Russian liberalism.[19]

Bibliography

Novels

- 1857 – Rudin

- 1859 – Home of the Gentry (Дворянское гнездо), also translated as A Nest of Gentlefolk, A House of Gentlefolk and Liza

- 1860 – On the Eve (Накануне)

- 1862 – Fathers and Sons (Отцы и дети), also translated as Fathers and Children

- 1867 – Smoke (Дым)

- 1872 – Torrents of Spring (Вешние воды)

- 1877 – Virgin Soil (Новь)

Selected shorter fiction

- 1850 – Dnevnik lishnevo cheloveka (Дневник лишнего человека); novella, English translation: The Diary of a Superfluous Man

- 1852 – Zapiski okhotnika (Записки охотника); collection of stories, English translations: A Sportsman's Sketches, The Hunter's Sketches, A Sportsman's Notebook

- 1854 – Mumu (Муму); short story, English translation: Mumu

- 1855 – Yakov Pasynkov (Яков Пасынков); novella

- 1855 – Faust (Фауст); novella

- 1858 – Asya (Ася); novella, English translation: Asya or Annouchka

- 1860 – Pervaya lyubov (Первая любовь); novella, English translation: First Love

- 1870 – Stepnoy korol Lir (Степной король Лир); novella, English translation: King Lear of the Steppes

- 1881 – Pesn torzhestvuyushchey lyubvi (Песнь торжествующей любви); novella, English translation: The Song of Triumphant Love

- 1883 – Klara Milich (Клара Милич); novella, English translation: The Mysterious Tales

Plays

- 1843 – A Rash Thing to Do (Неосторожность)

- 1847 – It Tears Where It is Thin (Где тонко, там и рвётся)

- 1849/1856 –Breakfast at the Chief's (Завтрак у предводителя)

- 1850/1851 – A Conversation on the Highway (Разговор на большой дороге)

- 1846/1852 – Lack of Money (Безденежье)

- 1851 – A Provincial Lady (Провинциалка)

- 1857/1862 – Fortune's Fool (Нахлебник), also translated as The Hanger-On and The Family Charge

- 1855/1872 – A Month in the Country (Месяц в деревне)

- 1882 – An Evening in Sorrento (Вечер в Сорренто)

Other

- 1877—1882 – Poems in Prose (Стихотворения в прозе)

See also

- Alexander Dmitriyevich Kastalsky who composed an opera based on the novella Klara Milich

- Sir Frederick Ashton, who created a ballet based on A Month in the Country in 1976

- Asteroid 3323 Turgenev, named after the writer

- Lee Hoiby, an American composer and his opera based on A Month in the Country

- Vladimir Rebikov, who composed an opera based on Home of the Gentry in 1916

- Galina Ulanova, who advised her pupils to read such stories of Turgenev's as "Asya" or Torrents of Spring when preparing to dance Giselle

References

- In Turgenev's day, his name was written Иванъ Сергѣевичъ Тургеневъ.

- "Turgenev". Random House Webster's Unabridged Dictionary.

- Turgenev coat of arms by All-Russian Armorials of Noble Houses of the Russian Empire. Part 4, December 7, 1799 (in Russian)

- Richard Pipes, U.S.–Soviet Relations in the Era of Détente: a Tragedy of Errors, Westview Press (1981), p. 17.

- Lutovinov coat of arms by All-Russian Armorials of Noble Houses of the Russian Empire. Part 8, January 25, 1807 (in Russian)

- Yuri Lebedev (1990). Turgenev. Moscow: Molodaya Gvardiya, 608 pages, pp. 8–103 ISBN 5-235-00789-1

- Зайцев Б. К. Жизнь Тургенева. — Париж: YMCA Press, 1949. С. 14.

- One or more of the preceding sentences incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Morfill, William Richard (1911). "Turgueniev, Ivan". In Chisholm, Hugh (ed.). Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 27 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 417.

- Schapiro (1982). Turgenev, His Life and Times. Harvard University Press. p. 18. ISBN 9780674912977. Retrieved 1 February 2020.

- Harold Bloom, ed. (2003). Ivan Turgenev. Chelsea House Publishers. pp. 95–96. ISBN 9780791073995.

For example, Leonard Schapiro, Turgenev, His Life and Times (New York: Random, 1978) 214, writes about Turgenev's agnosticism as follows: "Turgenev was not a determined atheist; there is ample evidence which shows that he was an agnostic who would have been happy to embrace the consolations of religion, but was, except perhaps on some rare occasions, unable to do so"; and Edgar Lehrman, Turgenev's Letters (New York: Knopf, 1961) xi, presents still another interpretation for Turgenev's lack of religion, suggesting literature as a possible substitution: "Sometimes Turgenev's attitude toward literature makes us wonder whether, for him, literature was not a surrogate religion—something in which he could believe unhesitatingly, unreservedly, and enthusiastically, something that somehow would make man in general and Turgenev in particular a little happier."

- Ceelen, W, Creytens D, Michel L.: "The Cancer Diagnosis, Surgery and Cause of Death of Ivan Turgenev." Acta Chirurgica Belgica 115.3 (2015): 241–46.

- Spitzka EA. A study of the brains of six eminent scientists and scholars belonging to the American Anthropometric Society. Together with a description of the skull of Professor E D Cope. Trans Am Philos Soc 1907; 21: 175–308.

- Pravda 1988: 308

- Tolstoy said after Turgenev's death: "His stories of peasant life will forever remain a valuable contribution to Russian literature. I have always valued them highly. And in this respect none of us can stand comparison with him. Take, for example, Living Relic (Живые мощи), Loner (Бирюк), and so on. All these are unique stories. And as for his nature descriptions, these are true pearls, beyond the reach of any other writer!" Quoted by K.N. Lomunov, "Turgenev i Lev Tolstoi: Tvorcheskie vzaimootnosheniia", in S.E. Shatalov (ed.), I.S. Turgenev v sovremennom mire (Moscow: Nauka, 1987).

- See the "Influences" section in the Infobox of the article on Dostoyevsky for a reference to a study dealing with precisely this issue.

- Isaiah Berlin, Russian Thinkers (Penguin, 1994), pp. 264–305.

- See Karl Ernst Laage, Theodor Storm. Biographie (Heide: Boyens, 1999).

- See Henry James, European Writers & The Prefaces (The Library of America: New York, 1984).

- See Vladimir Nabokov, Lectures on Russian Literature (HBJ, San Diego: 1981).

- Chebankova, Elena (2014). "Contemporary Russian liberalism" (PDF). Post-Soviet Affairs. 30 (5): 341–69. doi:10.1080/1060586X.2014.892743. hdl:10.1080/1060586X.2014.892743. S2CID 144124311.

Sources

- Cecil, David. 1949. "Turgenev", in David Cecil, Poets and Story-tellers: A Book of Critical Essays. New York: Macmillan Co.: 123–38.

- Freeborn, Richard. 1960. Turgenev: the Novelist's Novelist, a Study. London: Oxford University Press.

- Magarshack, David. 1954. Turgenev: a Life. London: Faber and Faber.

- Sokolowska, Katarzyna. 2011. Conrad and Turgenev: Towards the Real. Boulder: Eastern European Monographs.

- Troyat, Henri. 1988. Turgenev. New York: Dutton.

- Yarmolinsky, Avrahm. 1959. Turgenev, the Man, his Art and his Age. New York: Orion Press.

External links

- Works by Ivan Turgenev in eBook form at Standard Ebooks

- Works by Ivan Turgenev at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about Ivan Turgenev at Internet Archive

- Works by Ivan Turgenev at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

- Ivan Turgenev poetry (in Russian)

- Online archive of Turgenev's novels in the original Russian (in Russian)

- Turgenev's works (in Russian)

- Turgenev Society (mainly in (in Russian))

- Turgenev Museum in Bougival (in French)

- Petri Liukkonen. "Ivan Turgenev". Books and Writers

- Turgenev Bibliography 1983– by Nicholas Žekulin

- The Novels of Ivan Turgenev: Symbols and Emblems by Richard Peace

- English translations of 4 Poetic Miniatures

- English translations of 4 late Prose Poems

- English translation of eight late prose poems by Alexander Stillmark in Modern Poetry in Translation, No.11 (1997).