United States Department of Agriculture

The United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) is the federal executive department responsible for developing and executing federal laws related to farming, forestry, rural economic development, and food. It aims to meet the needs of commercial farming and livestock food production, promotes agricultural trade and production, works to assure food safety, protects natural resources, fosters rural communities and works to end hunger in the United States and internationally. It is headed by the Secretary of Agriculture, who reports directly to the President of the United States and is a member of the president's Cabinet. The current secretary is Tom Vilsack, who has served since February 24, 2021.[2]

Seal of the U.S. Department of Agriculture | |

Logo of the U.S. Department of Agriculture | |

Flag of the U.S. Department of Agriculture | |

| Agency overview | |

|---|---|

| Formed | May 15, 1862 Cabinet status: February 15, 1889 |

| Preceding agency |

|

| Jurisdiction | U.S. federal government |

| Headquarters | Jamie L. Whitten Building 1301 Independence Avenue, S.W., Washington, D.C. 38°53′17″N 77°1′48″W |

| Employees | 105,778 (June 2007) |

| Annual budget | US$151 billion (2017)[1] |

| Agency executives |

|

| Website | USDA.gov |

Approximately 80% of the USDA's $141 billion budget goes to the Food and Nutrition Service (FNS) program. The largest component of the FNS budget is the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (formerly known as the Food Stamp program), which is the cornerstone of USDA's nutrition assistance.[3] The United States Forest Service is the largest agency within the department, which administers national forests and national grasslands that together comprise about 25% of federal lands.

Overview

The USDA is divided into different agencies:

- Agricultural Marketing Service (AMS)

- Agricultural Research Service (ARS)

- Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service (APHIS)

- Economic Research Service (ERS)

- Farm Service Agency (FSA)

- Food and Nutrition Service (FNS)

- Food Safety and Inspection Service (FSIS)

- Foreign Agricultural Service (FAS)

- Forest Service (FS)

- FPAC Business Center

- National Agricultural Statistics Service (NASS)

- National Institute of Food and Agriculture (NIFA)

- Natural Resources Conservation Service (NRCS)

- Risk Management Agency (RMA)

- Rural Development (RD)

- Rural Utilities Service (RUS)

- Rural Housing Service (RHS)

- Rural Business-Cooperative Service (RBS)[4]

Many of the programs concerned with the distribution of food and nutrition to people of the United States and providing nourishment as well as nutrition education to those in need are run by the Food and Nutrition Service. Activities in this program include the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program, which provides healthy food to over 40 million low-income and homeless people each month.[5] USDA is a member of the United States Interagency Council on Homelessness,[6] where it is committed to working with other agencies to ensure these mainstream benefits have been accessed by those experiencing homelessness.

The USDA also is concerned with assisting farmers and food producers with the sale of crops and food on both the domestic and world markets. It plays a role in overseas aid programs by providing surplus foods to developing countries. This aid can go through USAID, foreign governments, international bodies such as World Food Program, or approved nonprofits. The Agricultural Act of 1949, section 416 (b) and Agricultural Trade Development and Assistance Act of 1954, also known as Food for Peace, provides the legal basis of such actions. The USDA is a partner of the World Cocoa Foundation.

History

.jpg.webp)

The standard history is Gladys L. Baker, ed., Century of Service: The first 100 years of the United States Department of Agriculture (U.S. Department of Agriculture, 1963).[7]

Origins in the Patent Office

Early in its history, the American economy was largely agrarian. Officials in the federal government had long sought new and improved varieties of seeds, plants and animals for import into the United States. In 1829, by request of James Smithson out of a desire to further promulgate and diffuse scientific knowledge amongst the American people, the Smithsonian Institution was established, though it did not incorporate agriculture.[8] In 1837, Henry Leavitt Ellsworth became Commissioner of Patents in the Department of State. He began collecting and distributing new varieties of seeds and plants through members of the Congress and local agricultural societies. In 1839, Congress established the Agricultural Division within the Patent Office and allotted $1,000 for "the collection of agricultural statistics and other agricultural purposes."[9] Ellsworth's interest in aiding agriculture was evident in his annual reports that called for a public depository to preserve and distribute the various new seeds and plants, a clerk to collect agricultural statistics, the preparation of statewide reports about crops in different regions, and the application of chemistry to agriculture. Ellsworth was called the "Father of the Department of Agriculture."[10]

In 1849, the Patent Office was transferred to the newly created Department of the Interior. In the ensuing years, agitation for a separate bureau within the department or a separate department devoted to agriculture kept recurring.[8]

History

_-_NARA_-_512817.jpg.webp)

On May 15, 1862, Abraham Lincoln established the independent Department of Agriculture through the Morrill Act to be headed by a commissioner without Cabinet status. Staffed by only eight employees, the department was charged with conducting research and development related to "agriculture, rural development, aquaculture and human nutrition in the most general and comprehensive sense of those terms".[11] Agriculturalist Isaac Newton was appointed to be the first commissioner.[12] Lincoln called it the "people's department", owing to the fact that over half of the nation at the time was directly or indirectly involved in agriculture or agribusiness.[13]

In 1868, the department moved into the new Department of Agriculture Building in Washington, designed by famed D.C. architect Adolf Cluss. Located on the National Mall between 12th Street and 14th SW, the department had offices for its staff and the entire width of the Mall up to B Street NW to plant and experiment with plants.[14]

In the 1880s, varied advocacy groups were lobbying for Cabinet representation. Business interests sought a Department of Commerce and Industry, and farmers tried to raise the Department of Agriculture to Cabinet rank. In 1887, the House of Representatives and Senate passed separate bills giving Cabinet status to the Department of Agriculture and Labor, but the bill was defeated in conference committee after farm interests objected to the addition of labor. Finally, in 1889 the Department of Agriculture was given cabinet-level status.[15]

In 1887, the Hatch Act provided for the federal funding of agricultural experiment stations in each state. The Smith-Lever Act of 1914 then funded cooperative extension services in each state to teach agriculture, home economics, and other subjects to the public. With these and similar provisions, the USDA reached out to every county of every state.[16]

New Deal era

By 1933 the department was well established in Washington and very well known in rural America. In the agricultural field the picture was different. Statisticians created a comprehensive data-gathering arm in the Division of Crop and Livestock Estimates. Secretary Henry Wallace, a statistician, further strengthened the expertise by introducing sampling techniques. Professional economists ran a strong Bureau of Agricultural Economics. Most important was the agricultural experiment station system, a network of state partners in the land-grant colleges, which in turn operated a large field service in direct contact with farmers in practically every rural county. The department worked smoothly with a nationwide, well-organized pressure group, the American Farm Bureau Federation. It represented the largest commercial growers before Congress.[17]

As late as the Great Depression, farm work occupied a fourth of Americans. Indeed, many young people who moved to the cities in the prosperous 1920s returned to the family farm after the depression caused unemployment after 1929. The USDA helped ensure that food continued to be produced and distributed to those who needed it, assisted with loans for small landowners, and provided technical advice. Its Bureau of Home Economics, established in 1923, published shopping advice and recipes to stretch family budgets and make food go farther.[18]

Modern times

It was revealed on August 27, 2018, that the U.S. Department of Agriculture would be providing U.S. farmers with a farm aid package, which will total $4.7 billion in direct payments to American farmers. This package is meant to offset the losses farmers are expected to incur from retaliatory tariffs placed on American exports during the Trump tariffs.[19]

On 7 February 2022, the USDA announced the Partnerships for Climate-Smart Commodities, a $1 billion program that will test and verify the benefits of climate-friendly agricultural practices.[20]

In October 2022, the USDA announced a $1.3 billion debt relief program for about 36,000 farmers who had fallen behind on loan payments or facing foreclosures. The provisions in the Inflation Reduction Act of 2022 set aside $3.1 billion to help such farmers with high-risk operations caused by USDA-backed loans.[21]

Organization and component staff level

USDA's offices and agencies are listed below, with full-time equivalent staff levels according to the estimated FY2019 appropriation, as reported in USDA's FY2020 Congressional Budget Justification.[1]

| Component | FTE | |

|---|---|---|

| Staff Offices

Secretary of Agriculture |

Deputy Secretary of Agriculture | |

| Agriculture Buildings and Facilities | 82 | |

| Departmental Administration | 385 | |

| Hazardous Materials Management | 4 | |

| Office of Budget and Program Analysis | 45 | |

| Office of Civil Rights | 130 | |

| Office of Communications | 73 | |

| Office of Ethics | 20 | |

| Office of Hearings and Appeals | 77 | |

| Office of Homeland Security | 58 | |

| Office of Inspector General | 482 | |

| Office of Partnerships and Public Engagement | 44 | |

| Office of the Chief Economist | 64 | |

| Office of the Chief Financial Officer | 1,511 | |

| Office of the Chief Information Officer | 1,157 | |

| Office of the General Counsel | 252 | |

| Office of the Secretary | 113 | |

| Farm Production and Conservation

Under Secretary for Farm Production and Conservation |

Farm Service Agency

|

11,278 |

Risk Management Agency

|

450 | |

| Natural Resources Conservation Service | 10,798 | |

| Farm Production and Conservation Business Center | 1,879 (FY20 est.) | |

| Rural Development

Under Secretary for Rural Development |

Rural Housing Service, Rural Business-Cooperative Service, Rural Utilities Service | 4,389 |

| Food, Nutrition, and Consumer Services

Under Secretary for Food, Nutrition, and Consumer Services |

Food and Nutrition Service | 1,558 |

| Food Safety

Under Secretary for Food Safety |

Food Safety and Inspection Service | 9,332 |

| Natural Resources and Environment

Under Secretary for Natural Resources and Environment |

United States Forest Service | 30,539 |

| Marketing and Regulatory Programs

Under Secretary for Marketing and Regulatory Programs |

Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service | 7,901 |

| Agricultural Marketing Service | 3,694 | |

| Research, Education, and Economics

Under Secretary for Research, Education, and Economics |

Agricultural Research Service | 6,166 |

| National Institute of Food and Agriculture | 358 | |

| Economic Research Service | 330 | |

| National Agricultural Statistics Service | 937 | |

| Under Secretary of Agriculture for Trade and Foreign Agricultural Affairs[22] | Foreign Agricultural Service | 1,019 |

| Total | 93,253 | |

.jpg.webp)

Inactive Departmental Services

- Agricultural Stabilization and Conservation Service (ASCS) (became part of the Farm Service Agency in 1994)

- Animal Damage Control (renamed Wildlife Services)

- Soil Conservation Service (SCS) renamed Natural Resources Conservation Service

- Section of Vegetable Pathology, Division of Botany (1887–90)[23]

- Renamed Division of Vegetable Pathology (1890–95)[23]

Discrimination

Allegations have been made that throughout the agency's history its personnel have discriminated against farmers of various backgrounds, denying them loans and access to other programs well into the 1990s.[24] The effect of this discrimination has been the reduction in the number of African American farmers in the United States.[25] Though African American farmers have been the most hit by discriminatory actions by the USDA, women, Native Americans, Hispanics, and other minorities have experienced discrimination in a variety of forms at the hands of the USDA. The majority of these discriminatory actions have occurred through the Farm Service Agency, which oversees loan and assistance programs to farmers.[26]

In response to the Supreme Court's ruling of unconstitutionality of the Agricultural Adjustment Act, Congress enacted the Soil Conservation and Domestic Allotment Act of 1936, which established the Soil Conservation Service (SCS) which provided service to private landowners and encouraged subsidies that would relieve soil from excessive farming. The SCS in its early days were hesitant, especially in Southern jurisdictions, to hire Black conservationists. Rather than reaching out to Black students in universities for interviews and job opportunities, students had to reach out for the few opportunities granted to Black conservationists.[27]

As part of the 1964 Civil Rights Act, the USDA formally ended racial segregation among its staff.[28] In the 1999 Pigford v. Glickman class-action lawsuit brought by African American farmers, the USDA agreed to a billion-dollar settlement due to its patterns of discrimination in the granting of loans and subsidies to black farmers.[28] In 2011, a second round of payouts, Pigford II, was appropriated by Congress for $1.25 billion, although this payout, far too late to support the many who desperately needed financial assistance during 1999 lawsuit, only comes out to around $250,000 per farmer.[29]

A March 17, 2006 letter from the GAO about the Pigford Settlement indicated that "the court noted that USDA disbanded its Office of Civil Rights in 1983, and stopped responding to claims of discrimination."[30]

Pigford v. Glickman

Following long-standing concerns, black farmers joined a class action discrimination suit against the USDA filed in federal court in 1997.[31] An attorney called it "the most organized, largest civil rights case in the history of the country."[32] Also in 1997, black farmers from at least five states held protests in front of the USDA headquarters in Washington, D.C.[33] Protests in front of the USDA were a strategy employed in later years as the black farmers sought to keep national attention focused on the plight of the black farmers. Representatives of the National Black Farmers Association met with President Bill Clinton and other administration officials at the White House. And NBFA's president testified before the United States House Committee on Agriculture.[34]

In Pigford v. Glickman, U.S. Federal District Court Judge Paul L. Friedman approved the settlement and consent decree on April 14, 1999.[31] The settlement recognized discrimination against 22,363 black farmers, but the NBFA would later call the agreement incomplete because more than 70,000 were excluded.[35] Nevertheless, the settlement was deemed to be the largest-ever civil rights class action settlement in American history. Lawyers estimated the value of the settlement to be more than $2 billion.[36] Some farmers would have their debts forgiven.[37] Judge Friedman appointed a monitor to oversee the settlement.[36] Farmers in Alabama, Mississippi, Arkansas, and Georgia were among those affected by the settlement.[38]

The NBFA's president was invited to testify before congress on this matter numerous times following the settlement, including before the United States Senate Committee on Agriculture on September 12, 2000, when he testified that many farmers had not yet received payments and others were left out of the settlement. It was later revealed that one DoJ staff "general attorney" was unlicensed while she was handling black farmers' cases.[39] NBFA called for all those cases to be reheard.[40] The Chicago Tribune reported in 2004 that the result of such longstanding USDA discrimination was that black farmers had been forced out of business at a rate three times faster than white farmers. In 1920, 1 in 7 U.S. farmers was African-American, and by 2004 the number was 1 in 100. USDA spokesman Ed Loyd, when acknowledging that the USDA loan process was unfair to minority farmers, had claimed it was hard to determine the effect on such farmers.[41]

In 2006 the Government Accountability Office (GAO) issued a report highly critical of the USDA in its handling of the black farmers cases.[42] NBFA continued to lobby Congress to provide relief. NBFA's Boyd secured congressional support for legislation that would provide $100 million in funds to settle late-filer cases. In 2006 a bill was introduced into the House of Representatives and later the Senate by Senator George Felix Allen.[43] In 2007 Boyd testified before the United States House Committee on the Judiciary about this legislation. As the organization was making headway by gathering Congressional supporters in 2007 it was revealed that some USDA Farm Services Agency employees were engaged in activities aimed at blocking Congressional legislation that would aid the black farmers.[44] President Barack Obama, then a U.S. Senator, lent his support to the black farmers' issues in 2007.[45] A bill co-sponsored by Obama passed the Senate in 2007.[46]

In early June 2008 hundreds of black farmers, denied a chance to have their cases heard in the Pigford settlement, filed a new lawsuit against USDA.[47] The Senate and House versions of the black farmers bill, reopening black farmers discrimination cases, became law in June 2008.[48] Some news reports said that the new law could affect up to 74,000 black farmers.[49] In October 2008, the GAO issued a report criticizing the USDA's handling of discrimination complaints.[50] The GAO recommended an oversight review board to examine civil rights complaints.[51]

After numerous public rallies and an intensive NBFA member lobbying effort, Congress approved and Obama signed into law in December 2010 legislation that set aside $1.15 billion to resolve the outstanding black farmers' cases.[52] NBFA's John W. Boyd, Jr., attended the bill-signing ceremony at the White House. As of 2013, 90,000 African-American, Hispanic, female and Native American farmers had filed claims. It was reported that some had been found fraudulent, or transparently bogus. In Maple Hill, North Carolina by 2013, the number of successful claimants was four times the number of farms with 1 out of 9 African-Americans being paid, while "claimants were not required [by the USDA] to present documentary evidence that they had been unfairly treated or had even tried to farm." Lack of documentation is an issue complicated by the USDA practice of discarding denied applications after three years.[53]

Keepseagle v. Vilsack

In 1999, Native American farmers, discriminated in a similar fashion to black farmers, filed a class-action lawsuit against the USDA alleging loan discrimination under the ECOA and the APA. This case relied heavily on its predecessor, Pigford v. Glickman, in terms of the reasoning it set forth in the lawsuit.[26] Eventually, a settlement was reached between the plaintiffs and the USDA to the amount of up to $760 million, awardable through individual damages claims.[54] These claims could be used for monetary relief, debt relief, and/or tax relief. The filing period began June 29, 2011 and lasted 180 days.[55] Track A claimants would be eligible for up to $50,000, whereas Track B claimants would be eligible for up to $250,000 with a higher standard of proof.[55]

Garcia v. Vilsack

In 2000, similar to Pigford v. Glickman, a class-action lawsuit was filed in the U.S. District Court for the District of Columbia on behalf of Hispanic farmers alleging that the USDA discriminated against them in terms of credit transactions and disaster benefits, in direct violation of ECOA. As per the settlement, $1.33 billion is available for compensation in awards of up to $50,000 or $250,000, while an additional $160 million is available in debt relief.[26]

Love v. Vilsack

In 2001, similar to Garcia v. Vilsack, a class-action lawsuit was filed in the same court alleging discrimination on the basis of gender. A Congressional response to the lawsuit resulted in the passing of the Equality for Women Farmers Act, which created a system that would allow for allegations of gender discrimination to be heard against the USDA and enable claims for damages.[26]

Environmental justice initiatives

In their 2012 environmental justice strategy, the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) stated an ongoing desire to integrate environmental justice into its core mission and operations. In 2011, Secretary of Agriculture Tom Vilsack emphasized the USDA's focus on EJ in rural communities around the United States, as well as connecting with Indigenous Tribes and ensuring they understand and receive their environmental rights. USDA does fund programs with social and environmental equity goals; however, it has no staff dedicated solely to EJ.

Background

On February 16, 1994, President Clinton issued Executive Order 12898, "Federal Actions to Address Environmental Justice in Minority Populations and Low-Income Populations." Executive Order 12898 requires that achieving EJ must be part of each federal agency's mission. Under Executive Order 12898 federal agencies must:

- enforce all health and environmental statutes in areas with minority and low-income populations;

- ensure public participation;

- improve research and data collection relating to the health and environment of minority and low-income populations; and

- identify differential patterns of consumption of natural resources among minority and low-income populations.

The Executive Order also created an Interagency Working Group (IWG) consisting of 11 heads of departments and agencies.[56]

2012 Environmental Justice Strategy

On February 7, 2012, the USDA released a final Environmental Justice Strategic Plan identifying new and updated goals and performance measures beyond what USDA identified in a 1995 EJ strategy that was adopted in response to E.O. 12898.[57] Generally, USDA believes its existing technical and financial assistance programs provide solutions to environmental inequity, such as its initiatives on education, food deserts, and economic development in impacted communities.

Natural Resources and Environment Under Secretary Harris Sherman is the political appointee generally responsible for USDA's EJ strategy, with Patrick Holmes, a senior staffer to the Under Secretary, playing a coordinating role. USDA has no staff dedicated solely to EJ.[58]

Tribal development

USDA has had a role in implementing Michelle Obama's Let's Move campaign in tribal areas by increasing Bureau of Indian Education schools' participation in federal nutrition programs, by developing community gardens on tribal lands, and developing tribal food policy councils.[59]

More than $6.2 billion in Rural Development funding has been allocated for community infrastructure in Indian country and is distributed via 47 state offices that altogether cover the entire continental United States, Hawaii, and Alaska.[58] Such funding has been used for a variety of reasons:

Rural housing:

-single-family housing direct loans

-loan guarantees loans for very-low-income homeowners

-financing for affordable rental housing

-financing for farm laborers and their families

Community facilities:

-child and senior care centers

-emergency services

-healthcare institutions

-educational institutions

-tribal administration buildings

Business and cooperative programs:

-increased access to broadband connections

-tribal workplace development and employment opportunities

-sustainable renewable energy development

-regional food systems

-financing and technical assistance for entrepreneurs, including loans and lending

-increased access to capital through Tribal CDFIs

Utilities:

-increased access to 21st century telecommunications services

-reliable and affordable water and wastewater systems

-financing electric systems

-integrating electric smart-grid technologies[60]

Tribal relations

In 1997, the U.S. Forest Service (USFS) published a resource guide aimed at helping USFS officials with developing and maintaining relations with different tribal governments. To that end, and in coordination with the Forest Service's 4-point American Indian/Alaska Native policy, the resource guide discusses how to:

- Maintain a governmental relationship with Federally Recognized tribal governments.

- Implement Forest Service programs and activities honoring Indian treaty rights, and fulfill legally mandated trust responsibilities to the extent that they are determine applicable to National Forest System lands.

- Administer programs and activities to address and be sensitive to traditional Native religious beliefs and practices.

- Provide research, transfer of technology, and technical assistance to Indian governments.[61]

The USFS works to maintain good governmental relationships through regular intergovernmental meetings, acknowledgement of pre-existing tribal sovereignty, and a better general understanding of tribal government, which varies from tribe to tribe. Indian treaty rights and trust responsibilities are honored through visits to tribal neighbors, discussions of mutual interest, and attempts to honor and accommodate the legal positions of Indians and the federal government. Addressing and demonstrating sensitivity to Native religious beliefs and practices includes walking through Native lands and acknowledging cultural needs when implementing USFS activities. Providing research, technology, and assistance to Indian governments is shown through collaboration of ecological studies and sharing of various environmental technologies, as well as the inclusion of traditional Native practices in contemporary operations of the USFS.[61]

The Intertribal Technical Assistance Network works to improve access of tribal governments, communities and individuals to USDA technical assistance programs.[62]

Tribal Services/Cooperatives

The Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service provides APHIS Veterinary Services, which serve the tribal community by promoting and fostering safe animal trade and care. This includes prevention of pests and disease from herd and fisheries as well as surveys for diseases on or near Native American lands that can affected traditionally hunted wildlife.[63] The APHIS also provides Wildlife Services, which help with wildlife damage on Native lands. This includes emergency trainings, outreach, consultation, internship opportunities for students, and general education on damage reduction, livestock protection, and disease monitoring.[64]

Meanwhile, the Agricultural Marketing Service (AMS) is exploring a program to use meat from bisons raised on tribal land to supply AMS food distribution programs to tribes.[58]

Technical and financial assistance

The NRCS Strike Force Initiative has identified impoverished counties in Mississippi, Georgia and Arkansas to receive increased outreach and training regarding USDA assistance programs. USDA credits this increased outreach with generating a 196 percent increase in contracts, representing more than 250,000 acres of farmland, in its Environmental Quality Incentives Program.[62] In 2001, NRCS funded and published a study, "Environmental Justice: Perceptions of Issues, Awareness and Assistance," focused on rural, Southern "Black Belt" counties and analyzing how the NRCS workforce could more effectively integrate environmental justice into impacted communities.[65]

The Farm Services Agency in 2011 devoted $100,000 of its Socially Disadvantaged Farmers and Ranchers program budget to improving its outreach to counties with persistent poverty.[66] USDA's Risk Management Agency has initiated education and outreach to low-income farmers regarding use of biological controls, rather than pesticides, for pest control.[58] The Rural Utilities Service administers water and wastewater loans, including SEARCH Grants that are targeted to financially distressed, small rural communities and other opportunities specifically for Alaskan Native villages.[67][68]

Mapping

USFS has established several Urban Field Stations, to research urban natural resources' structure, function, stewardship, and benefits.[69] By mapping urban tree coverage, the agency hopes to identify and prioritize EJ communities for urban forest projects.[69]

Another initiative highlighted by the agency is the Food and Nutrition Service and Economic Research Service's Food Desert Locator.[70] The Locator provides a spatial view of food deserts, defined as a low-income census tract where a substantial number or share of residents has low access to a supermarket or large grocery store. The mapped deserts can be used to direct agency resources to increase access to fresh fruits and vegetables and other food assistance programs.[71]

Other

Private sector relationships

USDA formalized a relationship with the Global Food Safety Initiative (GFSI) in 2018. GFSI is a private organization where members of the Consumer Goods Forum have control over benchmarking requirements in recognition of private standards for food safety. In August 2018, USDA achieved Technical Equivalence against Version 7.1 of the GFSI Benchmarking Requirements for their Harmonized GAP Plus + certification programme,[72] where Technical Equivalence is limited to government-owned food safety certification programmes. This is misaligned with U.S. Government Policy and OMB Circular No. A-119[73] which instructs its agencies to adopt voluntary consensus standards before relying upon industry standards (private standards) or developing government standards.

Harmonized GAP Plus+ Standard (V. 3.0) was published in February 2021[74] with reference to GFSI Guidance Document Version 2020, Part III, ignoring reference to international standards and technical specifications ISO 22000 and ISO T/S 22002-3 Prerequisite Programmes for Farming. The USDA exception to OMB Circular No. A-119 might be attributed to lobbying and influence of Consumer Goods Forum members in Washington, D.C.[75] In November 2021, GFSI announced its Technical Equivalence was under strategic review explaining the assessment has raised concerns across many stakeholders.[76]

COVID-19 relief

During the COVID-19 pandemic, Congress allocated funding to the USDA to address the disturbances rippling through the agricultural sector. On April 17, 2020, U.S. Secretary of Agriculture Sonny Perdue announced the Coronavirus Food Assistance Program:[77]

The American food supply chain had to adapt, and it remains safe, secure, and strong, and we all know that starts with America's farmers and ranchers. This program will not only provide immediate relief for our farmers and ranchers, but it will also allow for the purchase and distribution of our agricultural abundance to help our fellow Americans in need.

This provided $16 billion for farmers and ranchers, and $3 billion to purchase surplus produce, dairy, and meat from farmers for distribution to charitable organizations. As part of the Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security Act (CARES) and the Families First Coronavirus Response Act (FFCRA), USDA has up to an additional $873.3 million available in Section 32 funding to purchase a variety of agricultural products for distribution to food banks, $850 million for food bank administrative costs and USDA food purchases.

Related legislation

Important legislation setting policy of the USDA includes the:

- 1890, 1891, 1897, 1906 Meat Inspection Act

- 1906: Pure Food and Drug Act

- 1914: Cotton Futures Act

- 1916: Federal Farm Loan Act

- 1917: Food Control and Production Acts

- 1921: Packers and Stockyards Act

- 1922: Grain Futures Act

- 1922: National Agricultural Conference

- 1923: Agricultural Credits Act

- 1930: Perishable Agricultural Commodities Act

- 1930: Foreign Agricultural Service Act

- 1933: Agricultural Adjustment Act (AAA)

- 1933: Farm Credit Act

- 1935: Resettlement Administration

- 1936: Soil Conservation and Domestic Allotment Act

- 1937: Agricultural Marketing Agreement Act

- 1941: National Victory Garden Program

- 1941: Steagall Amendment

- 1946: Farmers Home Administration

- 1946: National School Lunch Act PL 79-396

- 1946: Research and Marketing Act

- 1947: Federal Insecticide, Fungicide, and Rodenticide Act PL 80-104

- 1948: Hope-Aiken Agriculture Act PL 80-897

- 1949: Agricultural Act PL 81-439 (Section 416 (b))

- 1954: Food for Peace Act PL 83-480

- 1954: Agricultural Act PL 83-690

- 1956: Soil Bank Program authorized

- 1956: Mutual Security Act PL 84-726

- 1957: Federal Plant Pest Act PL 85-36

- 1957: Poultry Products Inspection Act PL 85-172

- 1958: Food Additives Amendment PL 85-929

- 1958: Humane Slaughter Act

- 1958: Agricultural Act PL 85-835

- 1961: Consolidated Farm and Rural Development Act PL 87-128

- 1964: Agricultural Act PL 88-297

- 1964: Food Stamp Act PL 88-525

- 1964: Federal Insecticide, Fungicide, and Rodenticide Act Extension PL 88-305

- 1965: Appalachian Regional Development Act

- 1965: Food and Agriculture Act PL 89-321

- 1966: Child Nutrition Act PL 89-642

- 1967: Wholesome Meat Act PL 90-201

- 1968: Wholesome Poultry Products Act PL 90-492

- 1970: Agricultural Act PL 91-524

- 1972: Federal Environmental Pesticide Control Act PL 92-516

- 1970: Environmental Quality Improvement Act

- 1970: Food Stamp Act PL 91-671

- 1972: Rural Development Act

- 1972: Rural Development Act Reform 3.31

- 1972: National School Lunch Act Amendments (Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants and Children) PL 92-433

- 1973: Agriculture and Consumer Protection Act PL 93-86

- 1974: Safe Drinking Water Act PL 93-523

- 1977: Food and Agriculture Act PL 95-113

- 1985: Food Security Act PL 99-198

- 1990: Food, Agriculture, Conservation, and Trade Act of 1990 PL 101-624 (This act includes the Organic Foods Production Act of 1990)

- 1996: Federal Agriculture Improvement and Reform Act PL 104-127

- 1996: Food Quality Protection Act PL 104-170

- 2000: Agriculture Risk Protection Act PL 106-224

- 2002: Farm Security and Rural Investment Act PL 107-171

- 2008: Food, Conservation, and Energy Act of 2008 PL 110-246

- 2010: Healthy, Hunger-Free Kids Act of 2010 PL 111-296

Images

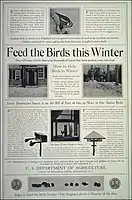

A 1918 call from the United States Department of Agriculture to feed birds in the winter.

A 1918 call from the United States Department of Agriculture to feed birds in the winter. A guide to improving farmhouse kitchens, put out by the department's Institute of Home Economics, Agricultural Research Service, in 1952

A guide to improving farmhouse kitchens, put out by the department's Institute of Home Economics, Agricultural Research Service, in 1952 A guide to making clothes, put out by the Institute of Home Economics in 1959

A guide to making clothes, put out by the Institute of Home Economics in 1959.JPG.webp) The Secretary of Agriculture's office is located in the Jamie L. Whitten Building.

The Secretary of Agriculture's office is located in the Jamie L. Whitten Building. USDA Visitor's Center in the Jamie L. Whitten Building.

USDA Visitor's Center in the Jamie L. Whitten Building.%252C_U.S._Department_of_Agriculture.jpg.webp) The Beagle Brigade is part of the USDA's Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service. This piece of luggage at Dulles Airport may contain contraband.

The Beagle Brigade is part of the USDA's Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service. This piece of luggage at Dulles Airport may contain contraband.

See also

- Adjusted Gross Revenue Insurance

- Alternative Agricultural Research and Commercialization Corporation

- Butter-Powder Tilt

- Congressional seed distribution

- Institute of Child Nutrition

- United States farm bill, history of Congressional laws on agriculture

- United States Agricultural Society

- USDA home loan

Notes and references

- "United States Department of Agriculture FY 2020 Budget Summary" (PDF). U.S. Department of Agriculture. Retrieved November 4, 2019.

- Good, Keith (February 24, 2021). "Senate Confirms Tom Vilsack as Secretary of Agriculture • Farm Policy News". Farm Policy News. Retrieved October 1, 2021.

- "History of FNS" (PDF). usda.gov. Archived from the original (PDF) on September 12, 2016. Retrieved July 1, 2016.

- "USDA Agencies".

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - "FNS Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP)". June 21, 2013. Retrieved December 29, 2013.

- "United States Interagency Council on Homelessness". USICH. Archived from the original on April 24, 2012.

- It is not copyright and is online here for free download..

- (PDF) https://permanent.fdlp.gov/gpo90633/HistoryofHumanNutritionResearch.pdf.

{{cite web}}: Missing or empty|title=(help)CS1 maint: url-status (link) - History of Human Nutrition Research in the U. S. Department of Agriculture. Government Printing Office. ISBN 9780160943843.

- "Ellsworth, Henry Leavitt, 1791–1858 – Social Networks and Archival Context". snaccooperative.org. Retrieved September 19, 2020.

- "Login".

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - 12 Stat. 387, now codified at 7 U.S.C. § 2201.

- Salvador, Ricardo; Bittman, Mark (December 4, 2020). "Opinion: Goodbye, U.S.D.A., Hello, Department of Food and Well-Being". The New York Times. Retrieved December 10, 2020.

- Evening Star – June 18, 1868 – page 4 – column 4

- 25 Stat 659 (February 9, 1889)

- Danbom, David B. (1986). "The Agricultural Experiment Station and Professionalization: Scientists' Goals for Agriculture". Agricultural History. 60 (2): 246–255. JSTOR 3743443.

- David M. Kennedy, Freedom from fear: The American people in depression and war, 1929–1945 (1999). p 203.

- Ziegelman, Jane; Coe, Andrew (2016). A Square Meal: A Culinary History of the Great Depression. HarperCollins. ISBN 978-0-06-221641-0.

- Reuters Editorial. "U.S. government to pay $4.7 billion in tariff-related aid to farmers". U.S. Retrieved August 28, 2018.

- Erickson, Britt. "USDA commits $1 billion to climate-smart agriculture". Chemical & Engineering News.

- Pitt, David (October 18, 2022). "USDA announces $1 billion debt relief for 36,000 farmers". Associated Press.

- "Secretary Perdue Announces Creation of Undersecretary for Trade". Retrieved June 16, 2018.

- "Records of the Bureau of Plant Industry, Soils, and Agricultural Engineering [BPISAE]: Administrative History". Archives.gov. Retrieved December 29, 2013.

- "USDA – Problems Continue to Hinder the Timely Processing of Discrimination Complaints" (PDF). General Accounting Office. January 1999.

- Brooks, Roy L. (2004). Atonement and Forgiveness: A New Model for Black Reparations. University of California Press. pp. 7–8. ISBN 0-520-24813-9.

- Garcia v. Vilsack: A Policy and Legal Analysis of a USDA Discrimination Case. , . HeinOnline, https://heinonline-org.ezproxy1.lib.asu.edu/HOL/P?h=hein.crs/crsmthmatal0001&i=11.

- Helms, Douglas. “Eroding the Color Line: The Soil Conservation Service and the Civil Rights Act of 1964.” Agricultural History, vol. 65, no. 2, Agricultural History Society, 1991, pp. 35–53, http://www.jstor.org/stable/3743706.

- Johnson, Kimberley S. (October 2011). "Racial Orders, Congress, and the Agricultural Welfare State, 1865–1940". Studies in American Political Development. 25 (2): 143–161. doi:10.1017/S0898588X11000095.

- "United States: Black US Farmers Awaiting Billions in Promised Debt Relief". Asia News Monitor. Bangkok. September 3, 2021. ProQuest 2568289864.

- "GAO-06-469R Pigford Settlement: The Role of the Court-Appointed Monitor" (PDF). Retrieved March 2, 2022.

- Tadlock Cowan and Jody Feder (June 14, 2011). "The Pigford Cases: USDA Settlement of Discrimination Suits by Black Farmers" (PDF). Congressional Research Service. Retrieved December 1, 2011.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link) - "PBS The News Hour (1999)". PBS. Retrieved December 29, 2013.

- Charlene Gilbert, Quinn Eli (2002). Homecoming: The Story of African-American Farmers. Beacon Press. ISBN 9780807009635. Retrieved December 29, 2013.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link) - Treatment of minority and limited resource producers by the U.S. Department of Agriculture: ... U.S. G.P.O. January 1, 1997. ISBN 9780160554100. Retrieved December 29, 2013.

- M. Susan Orr Klopfer, Fred Klopfer, Barry Klopfer (2005). Where Rebels Roost... Mississippi Civil Rights Revisited. Lulu Press. ISBN 9781411641020. Retrieved December 29, 2013.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link) - "Judge Approves Settlement for Black Farmers". New York Times. ASSOCIATED PRESS. April 15, 1999. Retrieved December 29, 2013.

- "Black Farmers Lawsuit". NPR. March 2, 1999. Retrieved December 29, 2013.

- "Southern farmers among those affected by court case". Archived from the original on July 11, 2012.

- Daniel Pulliam (February 11, 2005). "Unlicensed Hire". GOVEXEC.com. Archived from the original on April 16, 2005.

- "ABOUT US". nbfa. Retrieved August 6, 2020.

- Martin, Andrew (August 8, 2004). "USDA discrimination accused of withering black farmers". Chicago Tribune. Retrieved December 29, 2013.

- "Black Farmers Follow Up on USDA Grievances". National Public Radio. April 25, 2006. Retrieved December 29, 2013.

- "Allen Unveils Bill to Help Black Farmers". The Washington Post. Associated Press. September 29, 2006. Retrieved December 29, 2013.

- "Obama: USDA Should Not Undermine Legislation to Help Black Farmers". August 8, 2007. Archived from the original on November 11, 2008.

- "The Hill newspaper (2007)". Thehill.com. Retrieved December 29, 2013.

- Ben Evans (December 17, 2007). "Senate Votes to Reopen Black Farmers' Lawsuits". Associated Press. Archived from the original on October 30, 2008. Retrieved April 26, 2013.

- Ben Evans (June 4, 2008). "Black farmers file new suit against USDA". FOXNews.com. Associated Press. Retrieved December 29, 2013.

- Ben Evans (June 28, 2008). "Reopening black farmers' suits could cost billions". USA Today. Associated Press. Retrieved December 29, 2013.

- "Help Ahead for Black Farmers". NPR. December 31, 2007. Retrieved December 29, 2013.

- Etter, Lauren (October 23, 2008). "USDA Faulted Over Minority Farmers". The Wall Street Journal. Retrieved December 29, 2013.

- Fears, Darryl (October 23, 2008). "USDA Action On Bias Complaints Is Criticized". The Washington Post. Retrieved December 29, 2013.

- CNN Wire Staff (December 9, 2010). "Obama signs measure funding black farmers settlement". CNN.com. Archived from the original on October 31, 2012. Retrieved December 29, 2013.

- Sharon LaFraniere (April 25, 2013). "U.S. Opens Spigot After Farmers Claim Discrimination". The New York Times. Retrieved April 26, 2013.

...claimants were not required to present documentary evidence that they had been unfairly treated or had even tried to farm.

- "Native American Farmer and Rancher Class Action Settlement – Keepseagle v. Vilsack".

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - "Keepseagle settlement filing period open". Delta Farm Press, July 26, 2011. advance-lexis-com.ezproxy1.lib.asu.edu/api/document?collection=news&id=urn:contentItem:53F3-DGH1-DY7H-500C-00000-00&context=1516831. Accessed November 28, 2021.

- "Summary of Executive Order 12898 – Federal Actions to Address Environmental Justice in Minority Populations and Low-Income Populations". February 22, 2013.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - USDA, Strategic Plan, http://www.dm.usda.gov/hmmd/FinalUSDAEJSTRATScan_1.pdf Archived 2012-02-26 at the Wayback Machine

- Holmes interview.

- USDA, Strategic Plan at 6.

- "Collaborating for Prosperity With American Indians and Alaska Natives" (PDF).

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - Mitchell, Joe (1997). Forest Service National Resource Guide to American Indian and Alaska Native Relations. USFS.

- USDA, Progress Report at 8, http://www.dm.usda.gov/hmmd/FinalEJImplementationreport_1.pdf Archived 2012-02-26 at the Wayback Machine Report.

- APHIS Veterinary Services : Helping Native Americans Protect Their Livestock and Fisheries. United States Department of Agriculture, Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service, 2012.

- APHIS Wildlife Services : Controlling Wildlife Damage on Native American Lands. United States Department of Agriculture, Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service, 2012.

- USDA, NRCS EJ Guidance, https://www.nrcs.usda.gov/Internet/FSE_DOCUMENTS/stelprdb1045586.pdf.

- USDA, Progress Report at 9, http://www.dm.usda.gov/hmmd/FinalEJImplementationreport_1.pdf Archived 2012-02-26 at the Wayback Machine

- USDA, Water and Environmental Programs Fact Sheet, "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on June 25, 2012. Retrieved July 2, 2012.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - USDA, Water and Environmental Programs Website, http://www.rurdev.usda.gov/UWEP_HomePage.html Archived 2012-06-21 at the Wayback Machine

- USDA, Strategic Plan at 6, http://www.dm.usda.gov/hmmd/FinalUSDAEJSTRATScan_1.pdf Archived 2012-02-26 at the Wayback Machine

- "USDA ERS – Food Access Research Atlas". www.ers.usda.gov. Retrieved September 23, 2019.

- Velde interview.

- "GFSI Announces USDA AMS GAP Plus + Certification Programme Achieves Technical Equivalence". mygfsi.com/. GFSI.

- "OMB Circular A-119: Federal Participation in the Development and Use of Voluntary Consensus Standards and in Conformity Assessment Activities" (PDF). whitehouse.gov. The White House.

- "Harmonized GAP Plus+ Standard" (PDF). ams.usda.gov. USDA.

- Doering, Christopher. "Where the dollars go: Lobbying a big business for large food and beverage CPGs". fooddive.com. Food Dive.

- "GFSI Launches a Strategic Review of its Technical Equivalence Programme". mygfsi.com. GFSI.

- "USDA Announces Coronavirus Food Assistance Program". United States Department of Agriculture. April 17, 2020. Retrieved November 23, 2021.

Further reading

- Baker, Gladys L. ed. Century of service: the first 100 years of the United States Department of Agriculture (US Department of Agriculture, 1963), the standard history; online.

- Benedict, Murray R. (1950). "The Trend in American Agricultural Policy 1920–1949". Zeitschrift für die gesamte Staatswissenschaft. 106 (1): 97–122. JSTOR 40747300.

- Benedict, Murray R. Farm policies of the United States, 1790–1950: a study of their origins and development (1966) 546pp online; also another copy

- Cochrane, Willard W. The Development of American Agriculture: A Historical Analysis (2nd ed. U of Minnesota Press, 1993) 512pp.

- Cochrane, Willard W. and Mary Ellen Ryan. American Farm Policy: 1948–1973 (U of Minnesota Press, 1976).

- CQ. Congress and the Nation (1965–2021), highly detailed coverage of each presidency since Truman; extensive coverage of agricultural policies. online free to borrow

- Coppess, Jonathan (2018). The Fault Lines of Farm Policy: A Legislative and Political History of the Farm Bill. U of Nebraska Press. ISBN 978-1-4962-0512-4.

- Gardner, Bruce L. (1996). "The Federal Government in Farm Commodity Markets: Recent Reform Efforts in a Long-Term Context". Agricultural History. 70 (2): 177–195. JSTOR 3744532.

- Griesbach, Rob (2010). "BARC History: Bureau of Plant Industry" (PDF).

- Matusow, Allen J. Farm policies and politics in the Truman years (1967) online

- Orden, David; Zulauf, Carl (October 2015). "Political Economy of the 2014 Farm Bill". American Journal of Agricultural Economics. 97 (5): 1298–1311. doi:10.1093/ajae/aav028.

- Sumner, Daniel A. "Farm Subsidy Tradition and Modern Agricultural Realities" (PDF). CiteSeerX 10.1.1.411.284.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - Winters, Donald L. Henry Cantwell Wallace as Secretary of Agriculture, 1921–1924 (1970)

- Zulauf, Carl; Orden, David (2016). "80 Years of Farm Bills—Evolutionary Reform" (PDF). Choices. 31 (4): 1–2. JSTOR choices.31.4.16.

Historiography

- Zobbe, Henrik. "On the foundation of agricultural policy research in the United States." (Dept. of Agricultural Economics Staff Paper 02–08, Purdue University, 2002) online

Primary sources

- Rasmussen, Wayne D., ed. Agriculture in the United States: a documentary history (4 vol, Random House, 1975) 3661pp. vol 4 online

External links

- Official website

- Department of Agriculture on USAspending.gov

- Department of Agriculture in the Federal Register

- National Archives document of the USDA's origins

- Works by or about United States Department of Agriculture at Internet Archive (historic archives)

- Historic technical reports from USDA (and other federal agencies) are available in the Technical Report Archive and Image Library (TRAIL)

- USA: USDA Issues grants to support for robotics research

- USDA Awards $97 M for Renewable Energy Projects