Submarine communications cable

A submarine communications cable is a cable laid on the sea bed between land-based stations to carry telecommunication signals across stretches of ocean and sea. The first submarine communications cables laid beginning in the 1850s carried telegraphy traffic, establishing the first instant telecommunications links between continents, such as the first transatlantic telegraph cable which became operational on 16 August 1858. Subsequent generations of cables carried telephone traffic, then data communications traffic. Modern cables use optical fibre technology to carry digital data, which includes telephone, Internet and private data traffic.

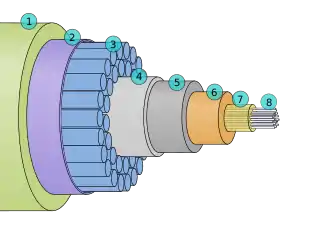

1 – Polyethylene

2 – Mylar tape

3 – Stranded steel wires

4 – Aluminium water barrier

5 – Polycarbonate

6 – Copper or aluminium tube

7 – Petroleum jelly

8 – Optical fibres

Modern cables are typically about 25 mm (1 in) in diameter and weigh around 1.4 tonnes per kilometre (2.5 short tons per mile; 2.2 long tons per mile) for the deep-sea sections which comprise the majority of the run, although larger and heavier cables are used for shallow-water sections near shore.[1][2] Submarine cables first connected all the world's continents (except Antarctica) when Java was connected to Darwin, Northern Territory, Australia, in 1871 in anticipation of the completion of the Australian Overland Telegraph Line in 1872 connecting to Adelaide, South Australia and thence to the rest of Australia.[3]

Early history: telegraph and coaxial cables

First successful trials

After William Cooke and Charles Wheatstone had introduced their working telegraph in 1839, the idea of a submarine line across the Atlantic Ocean began to be thought of as a possible triumph of the future. Samuel Morse proclaimed his faith in it as early as 1840, and in 1842, he submerged a wire, insulated with tarred hemp and India rubber,[4][5] in the water of New York Harbor, and telegraphed through it. The following autumn, Wheatstone performed a similar experiment in Swansea Bay. A good insulator to cover the wire and prevent the electric current from leaking into the water was necessary for the success of a long submarine line. India rubber had been tried by Moritz von Jacobi, the Prussian electrical engineer, as far back as the early 19th century.

Another insulating gum which could be melted by heat and readily applied to wire made its appearance in 1842. Gutta-percha, the adhesive juice of the Palaquium gutta tree, was introduced to Europe by William Montgomerie, a Scottish surgeon in the service of the British East India Company.[6]: 26–27 Twenty years earlier, Montgomerie had seen whips made of gutta-percha in Singapore, and he believed that it would be useful in the fabrication of surgical apparatus. Michael Faraday and Wheatstone soon discovered the merits of gutta-percha as an insulator, and in 1845, the latter suggested that it should be employed to cover the wire which was proposed to be laid from Dover to Calais.[7] In 1847 William Siemens, then an officer in the army of Prussia, laid the first successful underwater cable using gutta percha insulation, across the Rhine between Deutz and Cologne.[8] In 1849, Charles Vincent Walker, electrician to the South Eastern Railway, submerged 3 km (2 mi) of wire coated with gutta-percha off the coast from Folkestone, which was tested successfully.[6]: 26–27

First commercial cables

In August 1850, having earlier obtained a concession from the French government, John Watkins Brett's English Channel Submarine Telegraph Company laid the first line across the English Channel, using the converted tugboat Goliath. It was simply a copper wire coated with gutta-percha, without any other protection, and was not successful.[6]: 192–193 [9] However, the experiment served to secure renewal of the concession, and in September 1851, a protected core, or true, cable was laid by the reconstituted Submarine Telegraph Company from a government hulk, Blazer, which was towed across the Channel.[6]: 192–193 [10][7]

In 1853, more successful cables were laid, linking Great Britain with Ireland, Belgium, and the Netherlands, and crossing The Belts in Denmark.[6]: 361 The British & Irish Magnetic Telegraph Company completed the first successful Irish link on May 23 between Portpatrick and Donaghadee using the collier William Hutt.[6]: 34–36 The same ship was used for the link from Dover to Ostend in Belgium, by the Submarine Telegraph Company.[6]: 192–193 Meanwhile, the Electric & International Telegraph Company completed two cables across the North Sea, from Orford Ness to Scheveningen, the Netherlands. These cables were laid by Monarch, a paddle steamer which later became the first vessel with permanent cable-laying equipment.[6]: 195

In 1858, the steamship Elba was used to lay a telegraph cable from Jersey to Guernsey, on to Alderney and then to Weymouth, the cable being completed successfully in September of that year. Problems soon developed with eleven breaks occurring by 1860 due to storms, tidal and sand movements, and wear on rocks. A report to the Institution of Civil Engineers in 1860 set out the problems to assist in future cable-laying operations.[11]

Transatlantic telegraph cable

The first attempt at laying a transatlantic telegraph cable was promoted by Cyrus West Field, who persuaded British industrialists to fund and lay one in 1858.[7] However, the technology of the day was not capable of supporting the project; it was plagued with problems from the outset, and was in operation for only a month. Subsequent attempts in 1865 and 1866 with the world's largest steamship, the SS Great Eastern, used a more advanced technology and produced the first successful transatlantic cable. Great Eastern later went on to lay the first cable reaching to India from Aden, Yemen, in 1870.

British dominance of early cable

From the 1850s until 1911, British submarine cable systems dominated the most important market, the North Atlantic Ocean. The British had both supply side and demand side advantages. In terms of supply, Britain had entrepreneurs willing to put forth enormous amounts of capital necessary to build, lay and maintain these cables. In terms of demand, Britain's vast colonial empire led to business for the cable companies from news agencies, trading and shipping companies, and the British government. Many of Britain's colonies had significant populations of European settlers, making news about them of interest to the general public in the home country.

British officials believed that depending on telegraph lines that passed through non-British territory posed a security risk, as lines could be cut and messages could be interrupted during wartime. They sought the creation of a worldwide network within the empire, which became known as the All Red Line, and conversely prepared strategies to quickly interrupt enemy communications.[12] Britain's very first action after declaring war on Germany in World War I was to have the cable ship Alert (not the CS Telconia as frequently reported)[13] cut the five cables linking Germany with France, Spain and the Azores, and through them, North America.[14] Thereafter, the only way Germany could communicate was by wireless, and that meant that Room 40 could listen in.

The submarine cables were an economic benefit to trading companies, because owners of ships could communicate with captains when they reached their destination and give directions as to where to go next to pick up cargo based on reported pricing and supply information. The British government had obvious uses for the cables in maintaining administrative communications with governors throughout its empire, as well as in engaging other nations diplomatically and communicating with its military units in wartime. The geographic location of British territory was also an advantage as it included both Ireland on the east side of the Atlantic Ocean and Newfoundland in North America on the west side, making for the shortest route across the ocean, which reduced costs significantly.

A few facts put this dominance of the industry in perspective. In 1896, there were 30 cable-laying ships in the world, 24 of which were owned by British companies. In 1892, British companies owned and operated two-thirds of the world's cables and by 1923, their share was still 42.7 percent.[15] During World War I, Britain's telegraph communications were almost completely uninterrupted, while it was able to quickly cut Germany's cables worldwide.[12]

Cable to India, Singapore, East Asia and Australia

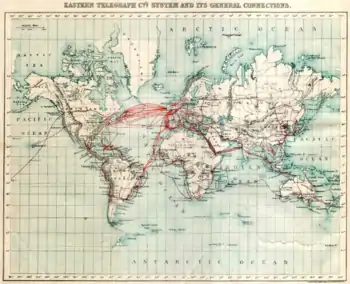

Throughout the 1860s and 1870s, British cable expanded eastward, into the Mediterranean Sea and the Indian Ocean. An 1863 cable to Bombay (now Mumbai), India, provided a crucial link to Saudi Arabia.[16] In 1870, Bombay was linked to London via submarine cable in a combined operation by four cable companies, at the behest of the British Government. In 1872, these four companies were combined to form the mammoth globe-spanning Eastern Telegraph Company, owned by John Pender. A spin-off from Eastern Telegraph Company was a second sister company, the Eastern Extension, China and Australasia Telegraph Company, commonly known simply as "the Extension". In 1872, Australia was linked by cable to Bombay via Singapore and China and in 1876, the cable linked the British Empire from London to New Zealand.[17]

Submarine cables across the Pacific

The first trans-Pacific cables providing telegraph service were completed in 1902 and 1903, linking the US mainland to Hawaii in 1902 and Guam to the Philippines in 1903.[18] Canada, Australia, New Zealand and Fiji were also linked in 1902 with the trans-Pacific segment of the All Red Line.[19] Japan was connected into the system in 1906. Service beyond Midway Atoll was abandoned in 1941 due to World War II, but the remainder remained in operation until 1951 when the FCC gave permission to cease operations.[20]

The first trans-Pacific telephone cable was laid from Hawaii to Japan in 1964, with an extension from Guam to The Philippines.[21] Also in 1964, the Commonwealth Pacific Cable System (COMPAC), with 80 telephone channel capacity, opened for traffic from Sydney to Vancouver, and in 1967, the South East Asia Commonwealth (SEACOM) system, with 160 telephone channel capacity, opened for traffic. This system used microwave radio from Sydney to Cairns (Queensland), cable running from Cairns to Madang (Papua New Guinea), Guam, Hong Kong, Kota Kinabalu (capital of Sabah, Malaysia), Singapore, then overland by microwave radio to Kuala Lumpur. In 1991, the North Pacific Cable system was the first regenerative system (i.e., with repeaters) to completely cross the Pacific from the US mainland to Japan. The US portion of NPC was manufactured in Portland, Oregon, from 1989 to 1991 at STC Submarine Systems, and later Alcatel Submarine Networks. The system was laid by Cable & Wireless Marine on the CS Cable Venture.

Construction

Transatlantic cables of the 19th century consisted of an outer layer of iron and later steel wire, wrapping India rubber, wrapping gutta-percha, which surrounded a multi-stranded copper wire at the core. The portions closest to each shore landing had additional protective armour wires. Gutta-percha, a natural polymer similar to rubber, had nearly ideal properties for insulating submarine cables, with the exception of a rather high dielectric constant which made cable capacitance high. William Thomas Henley had developed a machine in 1837 for covering wires with silk or cotton thread that he developed into a wire wrapping capability for submarine cable with a factory in 1857 that became W.T. Henley's Telegraph Works Co., Ltd.[22][23] The India Rubber, Gutta Percha and Telegraph Works Company, established by the Silver family and giving that name to a section of London, furnished cores to Henley's as well as eventually making and laying finished cable.[23] In 1870 William Hooper established Hooper's Telegraph Works to manufacture his patented vulcanized rubber core, at first to furnish other makers of finished cable, that began to compete with the gutta-percha cores. The company later expanded into complete cable manufacture and cable laying, including the building of the first cable ship specifically designed to lay transatlantic cables.[23][24][25]

Gutta-percha and rubber were not replaced as a cable insulation until polyethylene was introduced in the 1930s. Even then, the material was only available to the military and the first submarine cable using it was not laid until 1945 during World War II across the English Channel.[26] In the 1920s, the American military experimented with rubber-insulated cables as an alternative to gutta-percha, since American interests controlled significant supplies of rubber but did not have easy access to gutta-percha manufacturers. The 1926 development by John T. Blake of deproteinized rubber improved the impermeability of cables to water.[27]

Many early cables suffered from attack by sea life. The insulation could be eaten, for instance, by species of Teredo (shipworm) and Xylophaga. Hemp laid between the steel wire armouring gave pests a route to eat their way in. Damaged armouring, which was not uncommon, also provided an entrance. Cases of sharks biting cables and attacks by sawfish have been recorded. In one case in 1873, a whale damaged the Persian Gulf Cable between Karachi and Gwadar. The whale was apparently attempting to use the cable to clean off barnacles at a point where the cable descended over a steep drop. The unfortunate whale got its tail entangled in loops of cable and drowned. The cable repair ship Amber Witch was only able to winch up the cable with difficulty, weighed down as it was with the dead whale's body.[28]

Bandwidth problems

Early long-distance submarine telegraph cables exhibited formidable electrical problems. Unlike modern cables, the technology of the 19th century did not allow for in-line repeater amplifiers in the cable. Large voltages were used to attempt to overcome the electrical resistance of their tremendous length but the cables' distributed capacitance and inductance combined to distort the telegraph pulses in the line, reducing the cable's bandwidth, severely limiting the data rate for telegraph operation to 10–12 words per minute.

As early as 1816, Francis Ronalds had observed that electric signals were retarded in passing through an insulated wire or core laid underground, and outlined the cause to be induction, using the analogy of a long Leyden jar.[29][30] The same effect was noticed by Latimer Clark (1853) on cores immersed in water, and particularly on the lengthy cable between England and The Hague. Michael Faraday showed that the effect was caused by capacitance between the wire and the earth (or water) surrounding it. Faraday had noticed that when a wire is charged from a battery (for example when pressing a telegraph key), the electric charge in the wire induces an opposite charge in the water as it travels along. In 1831, Faraday described this effect in what is now referred to as Faraday's law of induction. As the two charges attract each other, the exciting charge is retarded. The core acts as a capacitor distributed along the length of the cable which, coupled with the resistance and inductance of the cable, limits the speed at which a signal travels through the conductor of the cable.

Early cable designs failed to analyse these effects correctly. Famously, E.O.W. Whitehouse had dismissed the problems and insisted that a transatlantic cable was feasible. When he subsequently became electrician of the Atlantic Telegraph Company, he became involved in a public dispute with William Thomson. Whitehouse believed that, with enough voltage, any cable could be driven. Thomson believed that his law of squares showed that retardation could not be overcome by a higher voltage. His recommendation was a larger cable. Because of the excessive voltages recommended by Whitehouse, Cyrus West Field's first transatlantic cable never worked reliably, and eventually short circuited to the ocean when Whitehouse increased the voltage beyond the cable design limit.

Thomson designed a complex electric-field generator that minimized current by resonating the cable, and a sensitive light-beam mirror galvanometer for detecting the faint telegraph signals. Thomson became wealthy on the royalties of these, and several related inventions. Thomson was elevated to Lord Kelvin for his contributions in this area, chiefly an accurate mathematical model of the cable, which permitted design of the equipment for accurate telegraphy. The effects of atmospheric electricity and the geomagnetic field on submarine cables also motivated many of the early polar expeditions.

Thomson had produced a mathematical analysis of propagation of electrical signals into telegraph cables based on their capacitance and resistance, but since long submarine cables operated at slow rates, he did not include the effects of inductance. By the 1890s, Oliver Heaviside had produced the modern general form of the telegrapher's equations, which included the effects of inductance and which were essential to extending the theory of transmission lines to the higher frequencies required for high-speed data and voice.

Transatlantic telephony

While laying a transatlantic telephone cable was seriously considered from the 1920s, the technology required for economically feasible telecommunications was not developed until the 1940s. A first attempt to lay a pupinized telephone cable failed in the early 1930s due to the Great Depression.

TAT-1 (Transatlantic No. 1) was the first transatlantic telephone cable system. Between 1955 and 1956, cable was laid between Gallanach Bay, near Oban, Scotland and Clarenville, Newfoundland and Labrador. It was inaugurated on September 25, 1956, initially carrying 36 telephone channels.

In the 1960s, transoceanic cables were coaxial cables that transmitted frequency-multiplexed voiceband signals. A high-voltage direct current on the inner conductor powered repeaters (two-way amplifiers placed at intervals along the cable). The first-generation repeaters remain among the most reliable vacuum tube amplifiers ever designed.[31] Later ones were transistorized. Many of these cables are still usable, but have been abandoned because their capacity is too small to be commercially viable. Some have been used as scientific instruments to measure earthquake waves and other geomagnetic events.[32]

Other uses

In 1942, Siemens Brothers of New Charlton, London, in conjunction with the United Kingdom National Physical Laboratory, adapted submarine communications cable technology to create the world's first submarine oil pipeline in Operation Pluto during World War II. Active fiber optic cables may be useful in detecting seismic events which alter cable polarization.[33]

Modern history

Optical telecommunications cables

| External image | |

|---|---|

In the 1980s, fibre-optic cables were developed. The first transatlantic telephone cable to use optical fibre was TAT-8, which went into operation in 1988. A fibre-optic cable comprises multiple pairs of fibres. Each pair has one fibre in each direction. TAT-8 had two operational pairs and one backup pair. Except for very short lines, fibre-optic submarine cables include repeaters at regular intervals.

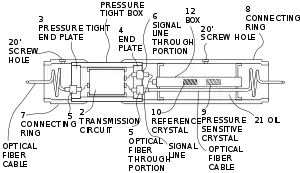

Modern optical fibre repeaters use a solid-state optical amplifier, usually an erbium-doped fibre amplifier. Each repeater contains separate equipment for each fibre. These comprise signal reforming, error measurement and controls. A solid-state laser dispatches the signal into the next length of fibre. The solid-state laser excites a short length of doped fibre that itself acts as a laser amplifier. As the light passes through the fibre, it is amplified. This system also permits wavelength-division multiplexing, which dramatically increases the capacity of the fibre.

Repeaters are powered by a constant direct current passed down the conductor near the centre of the cable, so all repeaters in a cable are in series. Power feed equipment is installed at the terminal stations. Typically both ends share the current generation with one end providing a positive voltage and the other a negative voltage. A virtual earth point exists roughly halfway along the cable under normal operation. The amplifiers or repeaters derive their power from the potential difference across them. The voltage passed down the cable is often anywhere from 3000 to 15,000VDC at a current of up to 1,100mA, with the current increasing with decreasing voltage; the current at 10,000VDC is up to 1,650mA. Hence the total amount of power sent into the cable is often up to 16.5 kW.[34][35]

The optic fibre used in undersea cables is chosen for its exceptional clarity, permitting runs of more than 100 kilometres (62 mi) between repeaters to minimize the number of amplifiers and the distortion they cause. Unrepeated cables are cheaper than repeated cables and their maximum transmission distance is limited, although this has increased over the years; in 2014 unrepeated cables of up to 380 kilometres (240 mi) in length were in service; however these require unpowered repeaters to be positioned every 100 km.[36]

The rising demand for these fibre-optic cables outpaced the capacity of providers such as AT&T. Having to shift traffic to satellites resulted in lower-quality signals. To address this issue, AT&T had to improve its cable-laying abilities. It invested $100 million in producing two specialized fibre-optic cable laying vessels. These included laboratories in the ships for splicing cable and testing its electrical properties. Such field monitoring is important because the glass of fibre-optic cable is less malleable than the copper cable that had been formerly used. The ships are equipped with thrusters that increase manoeuvrability. This capability is important because fibre-optic cable must be laid straight from the stern, which was another factor that copper-cable-laying ships did not have to contend with.[37]

Originally, submarine cables were simple point-to-point connections. With the development of submarine branching units (SBUs), more than one destination could be served by a single cable system. Modern cable systems now usually have their fibres arranged in a self-healing ring to increase their redundancy, with the submarine sections following different paths on the ocean floor. One reason for this development was that the capacity of cable systems had become so large that it was not possible to completely back up a cable system with satellite capacity, so it became necessary to provide sufficient terrestrial backup capability. Not all telecommunications organizations wish to take advantage of this capability, so modern cable systems may have dual landing points in some countries (where back-up capability is required) and only single landing points in other countries where back-up capability is either not required, the capacity to the country is small enough to be backed up by other means, or having backup is regarded as too expensive.

A further redundant-path development over and above the self-healing rings approach is the mesh network whereby fast switching equipment is used to transfer services between network paths with little to no effect on higher-level protocols if a path becomes inoperable. As more paths become available to use between two points, it is less likely that one or two simultaneous failures will prevent end-to-end service.

As of 2012, operators had "successfully demonstrated long-term, error-free transmission at 100 Gbps across Atlantic Ocean" routes of up to 6,000 km (3,700 mi),[38] meaning a typical cable can move tens of terabits per second overseas. Speeds improved rapidly in the previous few years, with 40 Gbit/s having been offered on that route only three years earlier in August 2009.[39]

Switching and all-by-sea routing commonly increases the distance and thus the round trip latency by more than 50%. For example, the round trip delay (RTD) or latency of the fastest transatlantic connections is under 60 ms, close to the theoretical optimum for an all-sea route. While in theory, a great circle route (GCP) between London and New York City is only 5,600 km (3,500 mi),[40] this requires several land masses (Ireland, Newfoundland, Prince Edward Island and the isthmus connecting New Brunswick to Nova Scotia) to be traversed, as well as the extremely tidal Bay of Fundy and a land route along Massachusetts' north shore from Gloucester to Boston and through fairly built up areas to Manhattan itself. In theory, using this partial land route could result in round trip times below 40 ms (which is the speed of light minimum time), and not counting switching. Along routes with less land in the way, round trip times can approach speed of light minimums in the long term.

The type of optical fiber used in unrepeated and very long cables is often PCSF (pure silica core) due to its low loss of 0.172 dB per kilometer when carrying a 1550 nm wavelength laser light. The large chromatic dispersion of PCSF means that its use requires transmission and receiving equipment designed with this in mind; this property can also be used to reduce interference when transmitting multiple channels through a single fiber using wavelength division multiplexing (WDM), which allows for multiple optical carrier channels to be transmitted through a single fiber, each carrying its own information. WDM is limited by the optical bandwidth of the amplifiers used to transmit data through the cable and by the spacing between the frequencies of the optical carriers; however this minimum spacing is also limited, with the minimum spacing often being 50 GHz (0.4 nm). The use of WDM can reduce the maximum length of the cable although this can be overcome by designing equipment with this in mind.

Optical post amplifiers, used to increase the strength of the signal generated by the optical transmitter often use a diode-pumped erbium-doped fiber laser. The diode is often a high power 980 or 1480 nm laser diode. This setup allows for an amplification of up to +24dBm in an affordable manner. Using an erbium-ytterbium doped fiber instead allows for a gain of +33dBm, however again the amount of power that can be fed into the fiber is limited. In single carrier configurations the dominating limitation is self phase modulation induced by the Kerr effect which limits the amplification to +18 dBm per fiber. In WDM configurations the limitation due to crossphase modulation becomes predominant instead. Optical pre-amplifiers are often used to negate the thermal noise of the receiver. Pumping the pre-amplifier with a 980 nm laser leads to a noise of at most 3.5 dB, with a noise of 5 dB usually obtained with a 1480 nm laser. The noise has to be filtered using optical filters.

Raman amplification can be used to extend the reach or the capacity of an unrepeatered cable, by launching 2 frequencies into a single fiber; one carrying data signals at 1550 nm, and the other pumping them at 1450 nm. Launching a pump frequency (pump laser light) at a power of just one watt leads to an increase in reach of 45 km or a 6-fold increase in capacity.

Another way to increase the reach of a cable is by using unpowered repeaters called remote optical pre-amplifiers (ROPAs); these still make a cable count as unrepeatered since the repeaters do not require electrical power but they do require a pump laser light to be transmitted alongside the data carried by the cable; the pump light and the data are often transmitted in physically separate fibers. The ROPA contains a doped fiber that uses the pump light (often a 1480 nm laser light) to amplify the data signals carried on the rest of the fibers.[36]

Importance of submarine cables

Currently 99% of the data traffic that is crossing oceans is carried by undersea cables.[41] The reliability of submarine cables is high, especially when (as noted above) multiple paths are available in the event of a cable break. Also, the total carrying capacity of submarine cables is in the terabits per second, while satellites typically offer only 1,000 megabits per second and display higher latency. However, a typical multi-terabit, transoceanic submarine cable system costs several hundred million dollars to construct.[42]

As a result of these cables' cost and usefulness, they are highly valued not only by the corporations building and operating them for profit, but also by national governments. For instance, the Australian government considers its submarine cable systems to be "vital to the national economy". Accordingly, the Australian Communications and Media Authority (ACMA) has created protection zones that restrict activities that could potentially damage cables linking Australia to the rest of the world. The ACMA also regulates all projects to install new submarine cables.[43]

Submarine cables are important to the modern military as well as private enterprise. The US military, for example, uses the submarine cable network for data transfer from conflict zones to command staff in the United States. Interruption of the cable network during intense operations could have direct consequences for the military on the ground.[44]

Investment and finances

Almost all fibre-optic cables from TAT-8 in 1988 until approximately 1997 were constructed by consortia of operators. For example, TAT-8 counted 35 participants including most major international carriers at the time such as AT&T Corporation.[45] Two privately financed, non-consortium cables were constructed in the late 1990s, which preceded a massive, speculative rush to construct privately financed cables that peaked in more than $22 billion worth of investment between 1999 and 2001. This was followed by the bankruptcy and reorganization of cable operators such as Global Crossing, 360networks, FLAG, Worldcom, and Asia Global Crossing. Tata Communications' Global Network (TGN) is the only wholly owned fiber network circling the planet.[46]

Most cables in the 20th century crossed the Atlantic Ocean, to connect the United States and Europe. However, capacity in the Pacific Ocean was much expanded starting in the 1990s. For example, between 1998 and 2003, approximately 70% of undersea fiber-optic cable was laid in the Pacific. This is in part a response to the emerging significance of Asian markets in the global economy.[47]

After decades of heavy investment in already developed markets such as the transatlantic and transpacific routes, efforts increased in the 21st century to expand the submarine cable network to serve the developing world. For instance, in July 2009, an underwater fibre-optic cable line plugged East Africa into the broader Internet. The company that provided this new cable was SEACOM, which is 75% owned by Africans.[48] The project was delayed by a month due to increased piracy along the coast.[49]

Investments in cables present a commercial risk because cables cover 6,200 km of ocean floor, cross submarine mountain ranges and rifts. Because of this most companies only purchase capacity after the cable is finished.[50][51][52][53]

Antarctica

Antarctica is the only continent not yet reached by a submarine telecommunications cable. Phone, video, and e-mail traffic must be relayed to the rest of the world via satellite links that have limited availability and capacity. Bases on the continent itself are able to communicate with one another via radio, but this is only a local network. To be a viable alternative, a fibre-optic cable would have to be able to withstand temperatures of −80 °C (−112 °F) as well as massive strain from ice flowing up to 10 metres (33 ft) per year. Thus, plugging into the larger Internet backbone with the high bandwidth afforded by fibre-optic cable is still an as-yet infeasible economic and technical challenge in the Antarctic.[54]

Cable repair

Cables can be broken by fishing trawlers, anchors, earthquakes, turbidity currents, and even shark bites.[55] Based on surveying breaks in the Atlantic Ocean and the Caribbean Sea, it was found that between 1959 and 1996, fewer than 9% were due to natural events. In response to this threat to the communications network, the practice of cable burial has developed. The average incidence of cable faults was 3.7 per 1,000 km (620 mi) per year from 1959 to 1979. That rate was reduced to 0.44 faults per 1,000 km per year after 1985, due to widespread burial of cable starting in 1980.[56] Still, cable breaks are by no means a thing of the past, with more than 50 repairs a year in the Atlantic alone,[57] and significant breaks in 2006, 2008, 2009 and 2011.

The propensity for fishing trawler nets to cause cable faults may well have been exploited during the Cold War. For example, in February 1959, a series of 12 breaks occurred in five American trans-Atlantic communications cables. In response, a United States naval vessel, the USS Roy O. Hale, detained and investigated the Soviet trawler Novorosiysk. A review of the ship's log indicated it had been in the region of each of the cables when they broke. Broken sections of cable were also found on the deck of the Novorosiysk. It appeared that the cables had been dragged along by the ship's nets, and then cut once they were pulled up onto the deck to release the nets. The Soviet Union's stance on the investigation was that it was unjustified, but the United States cited the Convention for the Protection of Submarine Telegraph Cables of 1884 to which Russia had signed (prior to the formation of the Soviet Union) as evidence of violation of international protocol.[58]

Shore stations can locate a break in a cable by electrical measurements, such as through spread-spectrum time-domain reflectometry (SSTDR), a type of time-domain reflectometry that can be used in live environments very quickly. Presently, SSTDR can collect a complete data set in 20 ms.[59] Spread spectrum signals are sent down the wire and then the reflected signal is observed. It is then correlated with the copy of the sent signal and algorithms are applied to the shape and timing of the signals to locate the break.

A cable repair ship will be sent to the location to drop a marker buoy near the break. Several types of grapples are used depending on the situation. If the sea bed in question is sandy, a grapple with rigid prongs is used to plough under the surface and catch the cable. If the cable is on a rocky sea surface, the grapple is more flexible, with hooks along its length so that it can adjust to the changing surface.[60] In especially deep water, the cable may not be strong enough to lift as a single unit, so a special grapple that cuts the cable soon after it has been hooked is used and only one length of cable is brought to the surface at a time, whereupon a new section is spliced in.[61] The repaired cable is longer than the original, so the excess is deliberately laid in a "U" shape on the seabed. A submersible can be used to repair cables that lie in shallower waters.

A number of ports near important cable routes became homes to specialized cable repair ships. Halifax, Nova Scotia, was home to a half dozen such vessels for most of the 20th century including long-lived vessels such as the CS Cyrus West Field, CS Minia and CS Mackay-Bennett. The latter two were contracted to recover victims from the sinking of the RMS Titanic. The crews of these vessels developed many new techniques and devices to repair and improve cable laying, such as the "plough".

Intelligence gathering

Underwater cables, which cannot be kept under constant surveillance, have tempted intelligence-gathering organizations since the late 19th century. Frequently at the beginning of wars, nations have cut the cables of the other sides to redirect the information flow into cables that were being monitored. The most ambitious efforts occurred in World War I, when British and German forces systematically attempted to destroy the others' worldwide communications systems by cutting their cables with surface ships or submarines.[62] During the Cold War, the United States Navy and National Security Agency (NSA) succeeded in placing wire taps on Soviet underwater communication lines in Operation Ivy Bells. In modern times, the widespread use of end-to-end encryption minimizes the threat of wire tapping.

Environmental impact

The main point of interaction of cables with marine life is in the benthic zone of the oceans where the majority of cable lies. Studies in 2003 and 2006 indicated that cables pose minimal impacts on life in these environments. In sampling sediment cores around cables and in areas removed from cables, there were few statistically significant differences in organism diversity or abundance. The main difference was that the cables provided an attachment point for anemones that typically could not grow in soft sediment areas. Data from 1877 to 1955 showed a total of 16 cable faults caused by the entanglement of various whales. Such deadly entanglements have entirely ceased with improved techniques for placement of modern coaxial and fibre-optic cables which have less tendency to self-coil when lying on the seabed.[63]

Security implications

Submarine cables are problematic from a security perspective because maps of submarine cables are widely available. Publicly available maps are necessary so that shipping can avoid damaging vulnerable cables by accident. However, the availability of the locations of easily damaged cables means the information is also easily accessible to criminal agents.[64] Governmental wiretapping also presents cybersecurity issues.[65]

Legal issues

Submarine cables suffer from inherent issues. Since cables are constructed and installed by private consortia, there is a problem with responsibility from the outset. Firstly, assigning responsibility inside a consortium can be hard: since there is no clear leading company which could be designated as responsible, it can lead to confusion when the cable needs maintenance. Secondly, it is hard to navigate the issue of cable damage through the international legal regime, since it was signed by and designed for nation states, rather than private companies. Thus it is hard to decide who should be responsible for damage costs and repairs – the company who built the cable, the company who paid for the cable, or the government of the countries where the cable terminates.[66]

Another legal issue is the outdating of legal systems. For example, Australia still uses fines which were set during the signing of the 1884 submarine cable treaty: 2000 Australian dollars, almost insignificant now.[67]

Influence of cable networks on modern history

Submarine communication cables have had a wide variety of influences over society. As well as allowing effective intercontinental trading and supporting stock exchanges, they greatly influenced international diplomatic conduct.[68] Before the existence of submarine communication connection, diplomats had much more power in their hands since their direct supervisors (governments of the countries which they represented) could not immediately check on them. Getting instructions to the diplomats in a foreign country often took weeks or even months. Diplomats had to use their own initiative in negotiations with foreign countries with only an occasional check from their government. This slow connection resulted in diplomats engaging in leisure activities while they waited for orders. The expansion of telegraph cables greatly reduced the response time needed to instruct diplomats. Over time, this led to a general decrease in prestige and power of individual diplomats within international politics and signalled a professionalization of the diplomatic corps who had to abandon their leisure activities.[69]

Notable events

In 1914, Germany raided the Fanning Island cable station in the Pacific.[70]

The Newfoundland earthquake of 1929 broke a series of transatlantic cables by triggering a massive undersea mudslide. The sequence of breaks helped scientists chart the progress of the mudslide.[71]

In 1986[72] during prototype and pre-production testing of the TAT-8 fiber-optic cable and its lay down procedures conducted by AT&T in the Canary Islands area, shark bite damage to the cable occurred. This revealed that sharks will dive to depths of 1 kilometre (0.62 mi), a depth which surprised marine biologists who until then thought that sharks were not active at such depths. The TAT-8 submarine cable connection was opened in 1988.[73]

In July 2005, a portion of the SEA-ME-WE 3 submarine cable located 35 kilometres (22 mi) south of Karachi that provided Pakistan's major outer communications became defective, disrupting almost all of Pakistan's communications with the rest of the world, and affecting approximately 10 million Internet users.[74][75][76]

On 26 December 2006, the 2006 Hengchun earthquakes rendered numerous cables between Taiwan and Philippines inoperable.[77]

In March 2007, pirates stole an 11-kilometre (7 mi) section of the T-V-H submarine cable that connected Thailand, Vietnam, and Hong Kong, afflicting Vietnam's Internet users with far slower speeds. The thieves attempted to sell the 100 tons of cable as scrap.[78]

The 2008 submarine cable disruption was a series of cable outages, two of the three Suez Canal cables, two disruptions in the Persian Gulf, and one in Malaysia. It caused massive communications disruptions to India and the Middle East.[79][80]

In April 2010, the undersea cable SEA-ME-WE 4 was under an outage. The Southeast Asia – Middle East – Western Europe 4 (SEA-ME-WE 4) submarine communications cable system, which connects Southeast Asia and Europe, was reportedly cut in three places, off Palermo, Italy.[81]

The 2011 Tōhoku earthquake and tsunami damaged a number of undersea cables that make landings in Japan, including:[82]

- APCN-2, an intra-Asian cable that forms a ring linking China, Hong Kong, Japan, the Republic of Korea, Malaysia, the Philippines, Singapore, and Taiwan

- Pacific Crossing West and Pacific Crossing North

- Segments of the East Asia Crossing network (reported by PacNet)

- A segment of the Japan–US Cable Network (reported by Korea Telecom)

- PC-1 submarine cable system (reported by NTT)

In February 2012, breaks in the EASSy and TEAMS cables disconnected about half of the networks in Kenya and Uganda from the global Internet.[83]

In March 2013, the SEA-ME-WE-4 connection from France to Singapore was cut by divers near Egypt.[84]

In November 2014, the SEA-ME-WE 3 stopped all traffic from Perth, Australia, to Singapore due to an unknown cable fault.[85]

In August 2017, a fault in IMEWE (India – Middle East – Western Europe) undersea cable near Jeddah, Saudi Arabia, disrupted the internet in Pakistan. The IMEWE submarine cable is an ultra-high capacity fibre optic undersea cable system which links India and Europe via the Middle East. The 12,091-kilometre-long (7,513 mi) cable has nine terminal stations, operated by leading telecom carriers from eight countries.[86]

AAE-1, spanning over 25,000 kilometres (16,000 mi), connects Southeast Asia to Europe via Egypt. Construction was finished in 2017.[87]

In June 2021, Google announced it was building the longest undersea cable in existence that would run from the east coast of the United States to Las Toninas, Argentina, with additional connections in Praia Grande, Brazil, and Punta del Este, Uruguay. The cable would ensure users fast, low-latency access to Google products, such as Search, Gmail and YouTube, as well as Google Cloud services.[88]

In August 2021, Google and Facebook announced that they would develop a subsea cable system, dubbed "Apricot", for 2024 in order to improve internet connectivity, and serve growing demand for broadband access and 5G wireless connectivity across the Asia-Pacific region, including Japan, Singapore, Taiwan, Guam, the Philippines and Indonesia.[89]

On 15 January 2022 the undersea eruption of the Hunga Tonga Hunga Ha'apai volcano broke the single international cable to Tonga, and at least one of Tonga's inter-island cables, severely disrupting communications to the rest of the world and leaving only limited satellite communications. The expected repair will take until mid February 2022. The repair ship will sail 4,000 km from Port Moresby, Papua New Guinea, via Samoa to collect spare cable for repair.[90][91]

On 20th October 2022 the under sea cable (SHEFA-2) between Banff UK mainland and the Shetland Islands was damaged. A full telecom and broadband outage was reported on the Shetland Islands, effectively rendering all emergency telecommunications inoperable. The undersea cable between the Shetland Islands and the Faroe Islands was also rendered damaged which contributed to the lack of redundancy and full telecommunications outage. It was reported that fishing activity contributed to the damage, however other sources speculate that severance of the cables to be a dry run by the Russian state in an attempt to prepare for future attacks on transatlantic fiber optic cables.

See also

- Bathometer

- Cable layer

- Cable landing point

- List of domestic submarine communications cables

- List of international submarine communications cables

- Loaded submarine cable

- Submarine power cable

- Transatlantic communications cable

References

- "How Submarine Cables are Made, Laid, Operated and Repaired", TechTeleData

- "The internet's undersea world" Archived 2010-12-23 at the Wayback Machine – annotated image, The Guardian.

- Anton A. Huurdeman, The Worldwide History of Telecommunications, pp. 136–140, John Wiley & Sons, 2003 ISBN 0471205052.

- [Heroes of the Telegraph – Chapter III. – Samuel Morse] "Globusz – Libros y más libros". Archived from the original on April 14, 2013. Retrieved 2008-02-05.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - "Timeline – Biography of Samuel Morse". Inventors.about.com. 2009-10-30. Retrieved 2010-04-25.

- Haigh, Kenneth Richardson (1968). Cable Ships and Submarine Cables. London: Adlard Coles. ISBN 9780229973637.

- Guarnieri, M. (2014). "The Conquest of the Atlantic". IEEE Industrial Electronics Magazine. 8 (1): 53–56/67. doi:10.1109/MIE.2014.2299492. S2CID 41662509.

- "C William Siemens". The Practical Magazine. 5 (10): 219. 1875.

- The company is referred to as the English Channel Submarine Telegraph Company

- Brett, John Watkins (March 18, 1857). "On the Submarine Telegraph". Royal Institution of Great Britain: Proceedings (transcript). II, 1854–1858. Archived from the original on 17 May 2013. Retrieved 17 May 2013.

- Minutes of Proceedings of the Institution of Civil Engineers. p. 26.

- Kennedy, P. M. (October 1971). "Imperial Cable Communications and Strategy, 1870–1914". The English Historical Review. 86 (341): 728–752. doi:10.1093/ehr/lxxxvi.cccxli.728. JSTOR 563928.

- Rhodri Jeffreys-Jones, In Spies We Trust: The Story of Western Intelligence, page 43, Oxford University Press, 2013 ISBN 0199580979.

- Jonathan Reed Winkler, Nexus: Strategic Communications and American Security in World War I, pages 5–6, 289, Harvard University Press, 2008 ISBN 0674033906.

- Headrick, D.R., & Griset, P. (2001). "Submarine Telegraph Cables: Business and Politics, 1838–1939". The Business History Review, 75(3), 543–578.

- "The Telegraph – Calcutta (Kolkata) | Frontpage | Third cable cut, but India's safe". Telegraphindia.com. 2008-02-03. Archived from the original on 2010-09-03. Retrieved 2010-04-25.

- "Landing the New Zealand cable", pg 3, The Colonist, 19 February 1876

- "Pacific Cable (SF, Hawaii, Guam, Phil) opens, President TR sends message July 4 in History". Brainyhistory.com. 1903-07-04. Retrieved 2010-04-25.

- "History of Canada-Australia Relations". Government of Canada. Archived from the original on 2014-07-20. Retrieved 2014-07-28.

- "The Commercial Pacific Cable Company". atlantic-cable.com. Atlantic Cable. Archived from the original on September 27, 2016. Retrieved September 24, 2016.

- "Milestones:TPC-1 Transpacific Cable System, 1964". ethw.org. Engineering and Technology History WIKI. Archived from the original on September 27, 2016. Retrieved September 24, 2016.

- "Machine used for covering wires with silk and cotton, 1837". The Science Museum Group. Retrieved 24 January 2020.

- Bright, Charles (1898). Submarine telegraphs: Their History, Construction, and Working. London: C. Lockwood and son. pp. 125, 157–160, 337–339. ISBN 9781108069489. LCCN 08003683. Retrieved 27 January 2020.

- Glover, Bill (7 February 2019). "History of the Atlantic Cable & Undersea Communications—CS Hooper/Silvertown". The Atlantic Cable. Retrieved 27 January 2020.

- Glover, Bill (22 December 2019). "History of the Atlantic Cable & Undersea Communications—British Submarine Cable Manufacturing Companies". The Atlantic Cable. Retrieved 27 January 2020.

- Ash, Stewart, "The development of submarine cables", ch. 1 in, Burnett, Douglas R.; Beckman, Robert; Davenport, Tara M., Submarine Cables: The Handbook of Law and Policy, Martinus Nijhoff Publishers, 2014 ISBN 9789004260320.

- Blake, J. T.; Boggs, C. R. (1926). "The Absorption of Water by Rubber". Industrial & Engineering Chemistry. 18 (3): 224–232. doi:10.1021/ie50195a002.

- "On Accidents to Submarine Cables", Journal of the Society of Telegraph Engineers, vol. 2, no. 5, pp. 311–313, 1873

- Ronalds, B.F. (2016). Sir Francis Ronalds: Father of the Electric Telegraph. London: Imperial College Press. ISBN 978-1-78326-917-4.

- Ronalds, B.F. (Feb 2016). "The Bicentennial of Francis Ronalds's Electric Telegraph". Physics Today. 69 (2): 26–31. Bibcode:2016PhT....69b..26R. doi:10.1063/PT.3.3079.

- "Learn About Submarine Cables". International Submarine Cable Protection Committee. Archived from the original on 2007-12-13. Retrieved 2007-12-30.. From this page: In 1966, after ten years of service, the 1,608 tubes in the repeaters had not suffered a single failure. In fact, after more than 100 million tube-hours over all, AT&T undersea repeaters were without failure.

- Butler, R.; A. D. Chave; F. K. Duennebier; D. R. Yoerger; R. Petitt; D. Harris; F.B. Wooding; A. D. Bowen; J. Bailey; J. Jolly; E. Hobart; J. A. Hildebrand; A. H. Dodeman. "The Hawaii-2 Observatory (H2O)" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 2008-02-26.

- Zhan, Zhongwen (26 February 2021). "Optical polarization–based seismic and water wave sensing on transoceanic cables". Science. 371 (6532): 931–936. Bibcode:2021Sci...371..931Z. doi:10.1126/science.abe6648. PMID 33632843. S2CID 232050549.

- Morris, Michael (April 19, 2009). "The Incredible International Submarine Cable Systems". Network World.

- Kaneko, Tomoyuki; Chiba, Yoshinori; Kunimi, Kaneaki; Nakamura, Tomotaka (2010). Very Compact and High Voltage Power Feeding Equipment (PFE) for Advanced Submarine Cable Network (PDF). SubOptic. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2020-08-08. Retrieved 2020-08-08.

- Tranvouez, Nicolas; Brandon, Eric; Fullenbaum, Marc; Bousselet, Philippe; Brylski, Isabelle. Unrepeatered Systems: State of the Art Capabiltiy (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2020-08-08. Retrieved 2020-08-08.

- Bradsher, Keith (15 August 1990). "New Fiber-Optic Cable Will Expand Calls Abroad, and Defy Sharks". The New York Times. Retrieved 14 January 2020.

- "Submarine Cable Networks – Hibernia Atlantic Trials the First 100G Transatlantic". Submarinenetworks.com. Archived from the original on 2012-06-22. Retrieved 2012-08-15.

- "Light Reading Europe – Optical Networking – Hibernia Offers Cross-Atlantic 40G – Telecom News Wire". Lightreading.com. Archived from the original on 2012-07-29. Retrieved 2012-08-15.

- "Great Circle Mapper". Gcmap.com. Archived from the original on 2012-07-25. Retrieved 2012-08-15.

- "Undersea Cables Transport 99 Percent of International Data". Newsweek. Retrieved 2016-11-16.

- Gardiner, Bryan (2008-02-25). "Google's Submarine Cable Plans Get Official" (PDF). Wired. Archived from the original on 2012-04-28.

- http://archive.acma.gov.au/WEB/STANDARD/1001/pc=PC_100223 Australian Communications and Media Authority. (2010, February 5). Submarine telecommunications cables.

- Clark, Bryan (15 June 2016). "Undersea cables and the future of submarine competition". Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists. 72 (4): 234–237. Bibcode:2016BuAtS..72d.234C. doi:10.1080/00963402.2016.1195636.

- Dunn, John (March 1987), "Talking the Light Fantastic", The Rotarian

- Dormon, Bob (26 May 2016). "How the Internet works: Submarine fiber, brains in jars, and coaxial cables". Ars Technica. Condé Nast. Retrieved November 28, 2020.

- Lindstrom, A. (1999, January 1). Taming the terrors of the deep. America's Network, 103(1), 5–16.

- "SEACOM - South Africa - East Africa - South Asia - Fiber Optic Cable". Archived from the original on 2010-02-08. Retrieved 2010-04-25. SEACOM (2010)

- McCarthy, Diane (2009-07-27). "Cable makes big promises for African Internet". CNN. Archived from the original on 2009-11-25.

- "'Visionary' fund for early stage European infrastructure backed by nations and EU". European Investment Bank. Retrieved 2021-04-16.

- "Background | Marguerite". 15 May 2013. Archived from the original on 2020-08-13. Retrieved 2021-04-16.

- James Griffiths (26 July 2019). "The global internet is powered by vast undersea cables. But they're vulnerable". CNN. Retrieved 2021-04-16.

- "Harnessing submarine cables to save lives". UNESCO. 2017-10-18. Retrieved 2021-04-16.

- Conti, Juan Pablo (2009-12-05), "Frozen out of broadband", Engineering & Technology, 4 (21): 34–36, doi:10.1049/et.2009.2106, ISSN 1750-9645, archived from the original on 2012-03-16

- Tanner, John C. (1 June 2001). "2,000 Meters Under the Sea". America's Network. bnet.com. Archived from the original on 8 July 2012. Retrieved 9 August 2009.

- Shapiro, S.; Murray, J.G.; Gleason, R.F.; Barnes, S.R.; Eales, B.A.; Woodward, P.R. (1987). "Threats to Submarine Cables" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2004-10-15. Retrieved 2010-04-25.

- John Borland (February 5, 2008). "Analyzing the Internet Collapse: Multiple fiber cuts to undersea cables show the fragility of the Internet at its choke points". Technology Review.

- The Embassy of the United States of America. (1959, March 24). U.S. note to Soviet Union on breaks in trans-Atlantic cables. The New York Times, 10.

- Smith, Paul, Furse, Cynthia, Safavi, Mehdi, and Lo, Chet. "Feasibility of Spread Spectrum Sensors for Location of Arcs on Live Wires Spread Spectrum Sensors for Location of Arcs on Live Wires." IEEE Sensors Journal. December, 2005. Archived December 31, 2010, at the Wayback Machine

- "When the ocean floor quakes" Popular Mechanics, vol.53, no.4, pp.618–622, April 1930, ISSN 0032-4558, pg 621: various drawing and cutaways of cable repair ship equipment and operations

- Clarke, A. C. (1959). Voice Across the Sea. New York, N.Y.: Harper & Row, Publishers, Inc.. p. 113

- Jonathan Reed Winkler, Nexus: Strategic Communications and American Security in World War I (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2008)

- Carter, L.; Burnett, D.; Drew, S.; Marle, G.; Hagadorn, L.; Bartlett-McNeil D.; Irvine N. (December 2009). "Submarine cables and the oceans: connecting the world" (PDF). p. 31. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2013-12-07. Retrieved 2013-08-02.

- Martinage, R (2015). "Under the Sea, vulnerability of commons". Foreign Affairs: 117–126.

- Emmott, Robin. "Brazil, Europe plan undersea cable to skirt U.S. spying". Reuters. Retrieved 5 July 2019.

- Davenport, Tara (2005). "Submarine Cables, Cybersecurity and International Law: An Intersectional Analysis". Catholic University Journal of Law and Technology. 24 (1): 57–109.

- Davenport, Tara (2015). "Submarine Cables, Cybersecurity and International Law: An Intersectional Analysis". The Catholic University Journal of Law and Technology: 83–84.

- Aitken, Frédéric; Foulc, Jean-Numa (2019). "Chap. 1". From deep sea to laboratory. 1 : the first explorations of the deep sea by H.M.S. Challenger (1872-1876). London.: ISTE-WILEY. ISBN 9781786303745.

- Paul, Nickles (2009). Bernard Finn; Daqing Yang (eds.). Communications Under the Seas: The Evolving Cable Network and Its Implications. MIT Press. pp. 209–226. ISBN 978-0-262-01286-7.

- Starosielski, Nicole. "In our Wi-Fi world, the internet still depends on undersea cables". The Conversation. Retrieved November 28, 2020.

- Fine, I. V.; Rabinovich, A. B.; Bornhold, B. D.; Thomson, R. E.; Kulikov, E. A. (2005). "The Grand Banks landslide-generated tsunami of November 18, 1929: preliminary analysis and numerical modeling" (PDF). Marine Geology. Elsevier. 215 (1–2): 45–47. Bibcode:2005MGeol.215...45F. doi:10.1016/j.margeo.2004.11.007. Archived from the original (PDF) on June 30, 2007.

- Douglas R. Burnett, Robert Beckman, Tara M. Davenport (eds), Submarine Cables: The Handbook of Law and Policy, p. 389, Martinus Nijhoff Publishers, 2013 ISBN 9004260331.

- Hecht, Jeff (2009). Bernard Finn; Daqing Yang (eds.). Communications Under the Seas: The Evolving Cable Network and Its Implications. MIT Press. p. 52. ISBN 978-0-262-01286-7.

- "Top Story: Standby Net arrangements terminated in Pakistan". Pakistan Times. Archived from the original on 2011-02-13. Retrieved 2010-04-25.

- "Communication breakdown in Pakistan – Breaking – Technology". The Sydney Morning Herald. 2005-06-29. Archived from the original on 2010-09-02. Retrieved 2010-04-25.

- "Pakistan cut off from the world". The Times of India. 2005-06-28. Archived from the original on 2012-10-22. Retrieved 2010-04-25.

- "Learning from Earthquakes The ML 6.7 (MW 7.1) Taiwan Earthquake of December 26, 2006" (PDF). Earthquake Engineering Research Institute. Archived from the original (PDF) on 21 November 2015. Retrieved 17 January 2017.

- "Vietnam's submarine cable 'lost' and 'found' at LIRNEasia". Lirneasia.net. Archived from the original on 2010-04-07. Retrieved 2010-04-25.

- "Finger-thin undersea cables tie world together – Internet – NBC News". NBC News. 2008-01-31. Retrieved 2010-04-25.

- "AsiaMedia: Bangladesh: Submarine Cable Snapped in Egypt". Asiamedia.ucla.edu. 2008-01-31. Archived from the original on 2010-09-01. Retrieved 2010-04-25.

- "SEA-ME-WE-4 Outage to Affect Internet and Telcom Traffic". propakistani.pk. Archived from the original on 2017-04-05. Retrieved 2017-04-04.

- PT (2011-03-14). "In Japan, Many Undersea Cables Are Damaged". Gigaom. Archived from the original on 2011-03-15. Retrieved 2011-03-16.

- See TEAMS (cable system) article.

- Kirk, Jeremy (27 March 2013). "Sabotage suspected in Egypt submarine cable cut". ComputerWorld. Archived from the original on 2013-09-25. Retrieved 2013-08-25.

- Grubb, Ben (2014-12-02). "Internet a bit slow today? Here's why". Archived from the original on 2016-10-11. Retrieved 2016-09-11.

- "IMEWE submarine cable fault". Archived from the original on 2018-04-27.

- "PTCL commissions Pakistan operations of AAE-1 submarine cable system".

- "Google underseas cable to ensure S. America has Google products". The Tokyo News. 13 June 2021.

- "Google and Facebook's New Cable to Link Japan and Southeast Asia". Bloomberg. 16 August 2021.

- "Tonga could be cut off from the outside world for more than two weeks, after volcano damages undersea cable". ABC News Aust. 18 January 2022.

- "Cable repair ship to set sail from PNG to restore communications to Tonga". www.stuff.co.nz. 17 January 2022.

Further reading

- Charles Bright (1898). Submarine Telegraphs: Their History, Construction, and Working. Crosby Lockward and Son. ISBN 9780665008672.

- Vary T. Coates and Bernard Finn (1979). A Retrospective Technology Assessment: The Transatlantic Cable of 1866. San Francisco Press.

- Bern Dibner (1959). The Atlantic Cable. Burndy Library.

- Bernard Finn; Daqing Yang, eds. (2009). Communications Under the Seas:The Evolving Cable Network and Its Implications. MIT Press.

- K.R. Haigh (1968). Cableships and Submarine Cables. United States Underseas Cable Corporation.

- Norman L. Middlemiss (2000). Cableships. Shield Publications.

- Nicole Starosielski (2015). The Undersea Network (Sign, Storage, Transmission). Duke University Press. ISBN 978-0822357551.

- A thread under the Ocean. World of Books. 2000. ISBN 978-0743231275.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|Author=ignored (|author=suggested) (help)

External links

- The International Cable Protection Committee – includes a register of submarine cables worldwide (though not always updated as often as one might hope)

- Timeline of Submarine Communications Cables, 1850–2010

- Kingfisher Information Service – Cable Awareness; UK Fisherman's Submarine Cable Awareness site

- Orange's Fishermen's/Submarine Cable Information

- Oregon Fisherman's Cable Committee

Articles

- History of the Atlantic Cable & Submarine Telegraphy – Wire Rope and the Submarine Cable Industry

- Mother Earth Mother Board – Wired article by Neal Stephenson about submarine cables

- Medford, L. V.; Meloni, A.; Lanzerotti, L. J.; Gregori, G. P. (1981-04-02). "Geomagnetic induction on a transatlantic communications cable". Nature. 290 (5805): 392–393. Bibcode:1981Natur.290..392M. doi:10.1038/290392a0. ISSN 1476-4687. S2CID 4330089. Retrieved 2022-07-21.

- Hunt, Bruce J. (2004). "Lord Cable". Europhysics News. 35 (6): 186. Bibcode:2004ENews..35..186H. doi:10.1051/epn:2004602. Archived from the original on 2005-02-26. Retrieved 2018-09-26.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - Winkler, Jonathan Reed. Nexus: Strategic Communications and American Security in World War I. (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2008) Account of how U.S. government discovered strategic significance of communications lines, including submarine cables, during World War I.

- Animations from Alcatel showing how submarine cables are installed and repaired

- Work begins to repair severed net

- Flexibility in Undersea Networks – Ocean News & Technology magazine Dec. 2014

Maps

- Submarine Cable Map by TeleGeography

- Map gallery of submarine cable maps by TeleGeography, showing evolution since 2000. 2008 map in the Guardian; 2014 map on CNN.

- Map and Satellite views of US landing sites for transatlantic cables

- Map and Satellite views of US landing sites for transpacific cables

- Positions and Route information of Submarine Cables in the Seas Around the UK