Tết

Tết (Vietnamese: [tet˧˥]), short for Tết Nguyên Đán (Chữ Hán: 節元旦), Spring Festival, Lunar New Year, or Vietnamese Lunar New Year is one of the most important celebrations in Vietnamese culture. The colloquial term "Tết" is a shortened form of Tết Nguyên Đán, with Old Vietnamese origins meaning "Festival of the First Morning of the First Day". Tết celebrates the arrival of spring based on the Vietnamese calendar, which usually has the date on January or February in the Gregorian calendar.[1]

| Vietnamese New Year | |

|---|---|

A family gathering to make bánh tét for Tết celebrations. | |

| Official name | Tết Nguyên Đán (節元旦) |

| Also called | Tết Lunar New Year (as a collective term including other Asian Lunar New Year festivals, used outside of Asia.) |

| Observed by | Vietnamese |

| Type | Religious, Cultural, and National. |

| Significance | The first day of the Lunar New Year |

| Celebrations | Lion dances, fireworks, family gathering, family meal, visiting friends' homes on the first day of the new year (xông đất), visiting friends and relatives, ancestor worship, giving red envelopes to children and elderly, and opening a shop. |

| Date | Lunar/Lunisolar New Year's Day |

| 2022 date | 1 February, Tiger |

| 2023 date | 22 January, Cat |

| Frequency | Annual |

| Related to | Chinese New Year, Korean New Year, Japanese New Year, Mongolian New Year, Tibetan New Year |

Tết Nguyên Đán (Spring Festival or Lunar New Year) is not to be confused with Tết Trung Thu (mid-autumn festival), which is also known as Children's Festival in Vietnam. Tết itself only means festival, but is often nominally known as "Lunar New Year Festival" in Vietnamese, as it is often seen as the most important festival amongst the Vietnamese diaspora, with Children's Festival (Mid-Autumn Festival) often regarded as the second-most important.[2][3]

Vietnamese people celebrate Tết annually, which is based on a lunisolar calendar (calculating both the motions of Earth around the Sun and of the Moon around Earth). Tết is generally celebrated on the same day as Chinese New Year (also called Spring Festival), except when the one-hour time difference between Vietnam and China results in the new moon occurring on different days. It takes place from the first day of the first month of the Vietnamese lunar calendar (around late January or early February) until at least the third day.

Tết is also an occasion for pilgrims and family reunions. They set aside the trouble of the past year and hoping for a better and happier upcoming year. This festival can also be referred to as Hội xuân in vernacular Vietnamese, (festival - lễ hội, spring - mùa xuân).[4]

Customs

Vietnamese people usually return to their families during Tết. Some return to worship at the family altar or visit graves of their ancestors in their homeland. They also clear up graves of their families as a sign of respect. Although Tết is a national holiday among all Vietnamese, each region and religion has its own customs.[4]

Many Vietnamese and Hoa people prepare for Tết by cooking special holiday food and doing house cleaning. These foods include bánh tét, bánh chưng, bánh dày, canh khổ qua, thịt kho hột vịt, dried young bamboo soup (canh măng), giò, and xôi (sticky rice). Many customs and traditions are practiced during Tết, such as visiting a person's house on the first day of the new year (xông nhà), ancestor worship, exchanging New Year's greetings, giving lucky money to children and elderly people, opening a shop, visiting relatives, friends and neighbors.

Tết can be divided into three periods, known as Tất Niên (penultimate New Year's Eve), Giao Thừa (New Year's Eve), and Tân Niên (the New Year), representing the preparation before Tết, the eve of Tết, and the days of and following Tết, respectively.[5]

The New Year in Tet

The first day of Tết is reserved for the nuclear family. Children receive red envelopes containing money from their elders. This tradition is called mừng tuổi (happy new age)[6] in the North region and lì xì in the South region. Usually, children wear their new clothes and give their elders the traditional Tết greetings before receiving money. Since the Vietnamese believe that the first visitor who a family receives in the year determines their fortune for the entire year, people never enter any house on the first day without being invited first. The action of being the first person to enter a house at Tết is called xông đất, xông nhà, or đạp đất, which is one of the most important rituals during Tết. According to Vietnamese tradition, if good things come to a family on the first day of the lunar New Year, the entire following year will also be full of blessings. Usually, a person of good temper, morality, and success will be a lucky sign for the host family and be first invited into his house. However, just to be safe, the owner of the house will leave the house a few minutes before midnight and come back just as the clock strikes midnight to prevent anyone else entering the house first who might potentially bring any unfortunate events in the new year, to the household.

Sweeping during Tết is taboo, or xui (unlucky), since it symbolizes sweeping the luck away; that is why they clean before the new year. It is also taboo for anyone who experienced a recent loss of a family member to visit anyone else during Tết.

During subsequent days, people visit relatives and friends. Traditionally but not strictly, the second day of Tết is usually reserved for friends, while the third day is for teachers, who command respect in Vietnam. Local Buddhist temples are popular spots because people like to give donations and get their fortunes told during Tết. Children are free to spend their new money on toys or on gambling games such as bầu cua cá cọp, which can be found in the streets. Prosperous families can pay for dragon dancers to perform at their house. Also, public performances are given for everyone to watch.

Traditional celebrations

These celebrations can last from a day up to the entire week, and the New Year is filled with people in the streets trying to make as much noise as possible using firecrackers, drums, bells, gongs, and anything they can think of to ward off evil spirits. This parade will also include different masks and dancers hidden under the guise of what is known as the múa lân or lion dancing. The lân is an animal between a lion and a dragon and is the symbol of strength in the Vietnamese culture that is used to scare away evil spirits. After the parade, families, and friends come together to have a feast of traditional Vietnamese dishes and share the happiness and joy of the New Year with one another. This is also the time when the elders will hand out red envelopes with money to the children for good luck in exchange for Tết greetings.

It is also a tradition to pay off your debts before the Vietnamese New Year for some Vietnamese families.[7]

Decorations

Traditionally, each family displays cây nêu, an artificial New Year tree consisting of a bamboo pole 5–6 m (16–20 ft) long. The top end is usually decorated with many objects, depending on the locality, including good luck charms, origami fish, cactus branches and more.

At Tết, every house is usually decorated by Yellow Apricot blossoms (hoa mai) in the central and southern parts of Vietnam, peach blossoms (hoa đào) in the northern part of Vietnam, or St. John's wort (hoa ban) in the mountain areas. In the north, some people (especially the elite in the past) also decorate their house with plum blossoms (also called hoa mơ in Vietnamese but referring to a totally different species from mickey-mouse blossoms). In the north or central, the kumquat tree is a popular decoration for the living room during Tết. Its many fruits symbolize the fertility and fruitfulness for which the family hopes in the coming year.

Vietnamese people also decorate their homes with bonsai and flowers such as chrysanthemums (hoa cúc), marigolds (vạn thọ) symbolizing longevity, cockscombs (mào gà) in southern Vietnam, and paperwhites (thủy tiên) and pansies (hoa lan) in northern Vietnam. In the past, there was a tradition where people tried to make their paperwhites bloom on the day of the observance.

They also hung up Dong Ho paintings and thư pháp calligraphy pictures.

Greetings

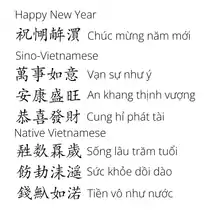

The traditional greetings are "Chúc Mừng Năm Mới" (祝𢜠𢆥㵋, Happy New Year) and "Cung Chúc Tân Xuân", (恭祝新春, gracious wishes of the new spring). People also wish each other prosperity and luck. Common wishes for Tết include the following:

- Sống lâu trăm tuổi: (𤯩𥹰𤾓歲, Live long for a hundred years!): used by children for elders. Traditionally, everyone is considered one year older on Tết, so children would wish their grandparents health and longevity in exchange for mừng tuổi 𢜠歲 or lì xì 利市 (SV: lợi thị).

- An khang thịnh vượng: (安康興旺, security, good health, and prosperity)

- Vạn sự như ý: (萬事如意, may things go your way)

- Sức khỏe dồi dào: (飭劸洡𤁠, Plenty of health!)

- Làm ăn tấn tới: (爫咹晉𬧐, Be successful at work!)

- Tiền vô như nước: (錢𠓺如渃, May money flow in like water!). Used informally.

- Cung hỉ phát tài: (恭喜發財, Congratulations and best wishes for a prosperous New Year!)

- Năm mới thắng lợi mới: (𢆥㵋勝利㵋, New year, new triumphs!; often heard in political speech)

- Chúc hay ăn chóng lớn: (祝𫨩咹𢶢𡘯, Eat well, grow quick!; aimed at children)

- Năm mới thăng quan tiến chức: (𢆥㵋陞官進織, I wish for you to be promoted in the new year!)

- Năm mới toàn gia bình an: (𢆥㵋全家平安, I wish that the new year will bring health and peace to your family!)

Food

In the Vietnamese language, to celebrate Tết is to ăn Tết, literally meaning "eat Tết", showing the importance of food in its celebration. Some of the food is also eaten year-round, while other dishes are only eaten during Tết. Also, some of the food is vegetarian since it is believed to be good luck to eat vegetarian on Tết. Some traditional foods on Tết include the following:

- Bánh chưng and bánh tét: essentially tightly packed sticky rice with meat or bean fillings wrapped in dong (Phrynium placentarium) leaves. When these leaves are unavailable, banana leaves can be used as a substitute. One difference between them is their shape. Bánh chưng is the square-shaped one to represent the Earth, while bánh tét is cylindrical to represent the moon. Also, bánh chưng is more popular in the northern parts of Vietnam, so as bánh tét is more popular in the south. Preparation can take days. After moulding them into their respective shapes (the square shape is achieved using a wooden frame), they are boiled for several hours to cook. The story of their origins and their connection with Tết is often recounted to children while cooking them overnight.

- Hạt dưa: roasted watermelon seeds, also eaten during Tết

- Dưa hành: pickled onion and pickled cabbage

- Củ kiệu: pickled small leeks

- Mứt: These dried candied fruits are rarely eaten at any time besides Tết.

- Kẹo dừa: coconut candy

- Kẹo mè xửng: peanut brittle with sesame seeds or peanuts

- Cầu sung dừa Đủ xoài: In southern Vietnam, popular fruits used for offerings at the family altar in fruit arranging art are the custard-apple/sugar-apple/soursop (mãng cầu), coconut (dừa), goolar fig (sung), papaya (đu đủ), and mango (xoài), since they sound like "cầu sung vừa đủ xài" ([We] pray for enough [money/resources/funds/goods/etc.] to use) in the southern dialect of Vietnamese.

- Thịt kho nước dừa Meaning "meat stewed in coconut juice", it is a traditional dish of pork belly and medium boiled eggs stewed in a broth-like sauce made overnight of young coconut juice and nuoc mam. It is often eaten with pickled bean sprouts and chives, and white rice.

- Xôi gấc: a red sticky rice made from gac fruit, typically paired with chả lụa (the most common type of sausage in Vietnamese cuisine, made of pork and traditionally wrapped in banana leaves).[8]

Forms of entertainment

People enjoy traditional games during Tết, including bầu cua cá cọp, cờ tướng, ném còn, chọi trâu, and đá gà. They also participate in some competitions presenting their knowledge, strength, and aestheticism, such as the bird competition and ngâm thơ competition.

Fireworks displays have also become a traditional part of a Tết celebration in Vietnam. During New Year's Eve, fireworks displays at major cities, such as Hà Nội, Ho Chi Minh City, and Da Nang, are broadcast through multiple national and local TV channels, accompanied by New Year wishes of the incumbent president. In 2017 only, fireworks displays were prohibited due to political and financial reasons. In 2021, due to COVID-19 epidemic, most provinces and cities cancelled the fireworks displays; instead, the displays were only held in Hà Nội and several provinces with public gatherings prohibited. In Australia, Canada & the United States, there are fireworks displays at many of its festivals, although in 2021 they were either held virtually or cancelled.

Gặp nhau cuối năm ("Year-end meet") is a nationally-known satirical theatrical comedy show, broadcast on VTV on New Year's Eve.

Dates in lunar calendar

From 1996 to 2067.

| Zodiac | Gregorian date | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tý (Rat) | 19 February 1996 | 7 February 2008 | 25 January 2020 | 11 February 2032 | 30 January 2044 | 15 February 2056 |

| Sửu (Buffalo) | 7 February 1997 | 26 January 2009 | 12 February 2021 | 31 January 2033 | 17 February 2045 | 4 February 2057 |

| Dần (Tiger) | 28 January 1998 | 14 February 2010 | 1 February 2022 | 19 February 2034 | 6 February 2046 | 24 January 2058 |

| Mẹo, Mão (Cat) | 16 February 1999 | 3 February 2011 | 22 January 2023 | 8 February 2035 | 26 January 2047 | 12 February 2059 |

| Thìn (Dragon) | 5 February 2000 | 23 January 2012 | 10 February 2024 | 28 January 2036 | 14 February 2048 | 2 February 2060 |

| Tỵ (Snake) | 24 January 2001 | 10 February 2013 | 29 January 2025 | 15 February 2037 | 2 February 2049 | 21 January 2061 |

| Ngọ (Horse) | 12 February 2002 | 31 January 2014 | 17 February 2026 | 4 February 2038 | 23 January 2050 | 9 February 2062 |

| Mùi (Goat) | 1 February 2003 | 19 February 2015 | 6 February 2027 | 24 January 2039 | 11 February 2051 | 29 January 2063 |

| Thân (Monkey) | 22 January 2004 | 8 February 2016 | 26 January 2028 | 12 February 2040 | 1 February 2052 | 17 February 2064 |

| Dậu (Rooster) | 9 February 2005 | 28 January 2017 | 13 February 2029 | 1 February 2041 | 18 February 2053 | 5 February 2065 |

| Tuất (Dog) | 29 January 2006 | 16 February 2018 | 2 February 2030 | 22 January 2042 | 8 February 2054 | 26 January 2066 |

| Hợi (Pig) | 17 February 2007 | 5 February 2019 | 23 January 2031 | 10 February 2043 | 28 January 2055 | 14 February 2067 |

See also

- List of Buddhist festivals

- Celebrations of Lunar New Year in other parts of Asia:

- Chinese New Year (Spring Festival)

- Korean New Year (Seollal)

- Japanese New Year (Shōgatsu)

- Mongolian New Year (Tsagaan Sar)

- Tibetan New Year (Losar)

- Similar Asian Lunisolar New Year celebrations that occur in April:

- Burmese New Year (Thingyan)

- Cambodian New Year (Chaul Chnam Thmey)

- Lao New Year (Pii Mai)

- Bengali New Year (Pahela Baisakh)

- Sri Lankan New Year (Aluth Avuruddu)

- Thai New Year (Songkran)

References

- "Tết Nguyên Đán The Vietnamese New Year". Archived from the original on 27 May 2013. Retrieved 12 June 2013.

- "Tết". escholarship.org. Retrieved 2022-02-12.

- Szymańska-Matusiewicz, Grażyna (2015). "The Two Tết Festivals: Transnational Connections and Internal Diversity of the Vietnamese Community in Poland". Central and Eastern European Migration Review. 4 (1): 53–65. ISSN 2300-1682.

- VietnamPlus (2021-02-12). "Unique traditional Tet customs of Vietnam | Society | Vietnam+ (VietnamPlus)". VietnamPlus. Retrieved 2022-02-12.

- Hornberger, Jake (2018-02-13). "Tet Holiday: The Age-Old Tradition Explained". Vietcetera. Retrieved 2022-02-12.

- "Vietnamese New Year – Learn about the traditions and customs of the Tet Holiday". Go Explore Vietnam. January 7, 2021. Retrieved August 5, 2021.

- Do, Anh (28 January 2017). "Vietnamese prepare for Lunar New Year by paying off debts, a tradition that can often bring stress". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 2017-01-28.

- "Xoi gac-gac sticky rice, fortunate red of Vietnam – Travel information for Vietnam from local experts". Travel information for Vietnam from local experts. Retrieved 2018-02-11.

External links

- Tet Nguyen Dan: The Vietnamese New Year - Queens Botanical Garden

- Vietnamese New Year customs

- Tet Holiday

- Vietnamese calendar rules - Hồ Ngọc Đức, Leipzig University.

- Tết - Vietnamese Lunar New Year Traditions

- Tet Festival Orange County Fairgrounds, Costa Mesa, CA

- Tet on Phu Quoc Island on Vietnam's largest island

- Tết Festival - San Francisco

- Vietnamese New Year – Learn about the traditions and customs of the Tet Holiday