Virgin birth of Jesus

The virgin birth of Jesus is the Christian doctrine that Jesus was conceived by his mother, Mary, through the power of the Holy Spirit and without sexual intercourse.[1] It is mentioned only in Matthew 1:18–25 and Luke 1:26–38,[2] and the modern scholarly consensus is that the narrative rests on very slender historical foundations.[3] The ancient world had no understanding that male semen and female ovum were both needed to form a fetus;[4] this cultural milieu was conducive to miraculous birth stories,[5] and tales of virgin birth and the impregnation of mortal women by deities were well known in the 1st-century Greco-Roman world and Second Temple Jewish works.[6][7]

| Part of a series on |

| Christianity |

|---|

|

Christians—Catholics, Protestants, Eastern Orthodox, Oriental Orthodox—traditionally regard the doctrine as an explanation of the mixture of the human and divine natures of Jesus.[8][1] The Eastern Orthodox Churches accept the doctrine as authoritative by reason of its inclusion in the Nicene Creed,[8] and the Catholic Church likewise holds it authoritative for faith through the Apostles' Creed as well as the Nicene. Nevertheless, there are many contemporary churches in which it is considered orthodox to accept the virgin birth but not heretical to deny it.[9]

Islam has upheld the virgin birth of Jesus (Isa).

New Testament narratives: Matthew and Luke

| Events in the |

| Life of Jesus according to the canonical gospels |

|---|

|

|

Portals: |

Matthew 1:18-25

18: Now the birth of Jesus the Messiah took place in this way. When his mother Mary had been engaged to Joseph, but before they lived together, she was found to be with child from the Holy Spirit.

19: Her husband Joseph, being a righteous man and unwilling to expose her to public disgrace, planned to dismiss her quietly.

20: But just when he had resolved to do this, an angel of the Lord appeared to him in a dream and said, "Joseph, son of David, do not be afraid to take Mary as your wife, for the child conceived in her is from the Holy Spirit.

21: She will bear a son, and you are to name him Jesus, for he will save his people from their sins."

22: All this took place to fulfill what had been spoken by the Lord through the prophet:

23: "Look, the virgin shall conceive and bear a son, and they shall name him Emmanuel," which means, "God is with us."

24: When Joseph awoke from sleep, he did as the angel of the Lord commanded him; he took her as his wife,

25: but had no marital relations with her until she had borne a son; and he named him Jesus.

Luke 1:26-38

26: In the sixth month the angel Gabriel was sent by God to a town in Galilee called Nazareth,

27: to a virgin engaged to a man whose name was Joseph, of the house of David. The virgin's name was Mary.

28: And he came to her and said, "Greetings, favored one! The Lord is with you."

29: But she was much perplexed by his words and pondered what sort of greeting this might be.

30: The angel said to her, "Do not be afraid, Mary, for you have found favor with God.

31: And now, you will conceive in your womb and bear a son, and you will name him Jesus.

32: He will be great, and will be called the Son of the Most High, and the Lord God will give to him the throne of his ancestor David.

33: He will reign over the house of Jacob forever, and of his kingdom there will be no end."

34: Mary said to the angel, "How can this be, since I am a virgin?"

35: The angel said to her, "The Holy Spirit will come upon you, and the power of the Most High will overshadow you; therefore the child to be born will be holy; he will be called Son of God.

36: And now, your relative Elizabeth in her old age has also conceived a son; and this is the sixth month for her who was said to be barren.

37: For nothing will be impossible with God."

38: Then Mary said, "Here am I, the servant of the Lord; let it be with me according to your word." Then the angel departed from her.

Texts

In the entire Christian corpus, the virgin birth is explicit only in the Gospel of Matthew and the Gospel of Luke.[2] The two agree that Mary's husband was named Joseph, that he was of the Davidic line, and that he played no role in Jesus's divine conception, but beyond this they are very different.[10][11] Matthew has no census, shepherds, or presentation in the temple, and implies that Joseph and Mary are living in Bethlehem at the time of the birth, while Luke has no magi, flight into Egypt or massacre of the infants, and states that Joseph lives in Nazareth.[10]

Matthew underlines the virginity of Mary by references to the Book of Isaiah (using the Greek translation in the Septuagint, rather than the mostly Hebrew Masoretic Text) and by his narrative statement that Joseph had no sexual relations with her until after the birth (a choice of words which leaves open the possibility that they did have relations after that).[12] Luke introduces Mary as a virgin, describes her puzzlement at being told she will bear a child despite her lack of sexual experience, and informs the reader that this pregnancy is to be effected through God's Holy Spirit.[13] The account has obvious problems: why would Mary, betrothed and about to begin life with her husband, be puzzled at the idea that she will have a child, especially as there is nothing in the angel's words ("you will conceive in your womb and bear a son") to suggest that the child's conception will be other than natural.

There is a serious debate as to whether Luke's nativity story is an original part of his gospel.[14] Chapters 1 and 2 are written in a style quite different from the rest of the gospel, and the dependence of the birth narrative on the Greek Septuagint is absent from the remainder.[15] There are strong Lukan motifs in Luke 1–2, but differences are equally striking—Jesus's identity as "son of David", for example, is a prominent theme of the birth narrative, but not in the rest of the gospel.[16] In the early part of the 2nd century the gnostic theologian Marcion produced a version of Luke lacking these two chapters, and although he is generally accused of having cut them out of a longer text more like our own, genealogies and birth narratives are also absent from Mark and John.[15]

Cultural context

Matthew 1:18 says that Mary was betrothed (engaged) to Joseph.[17] Under Jewish law betrothal was only possible for minors, which for girls meant aged under twelve or prior to the first mense, whichever came first.[17] We can thus take it that Mary was twelve years old or a little less, at the time of the events described in the gospels[18] According to custom the wedding would take place twelve months later, after which the groom would take his bride from her father's house to his own.[18] A betrothed girl who had sex with a man other than her husband-to-be was considered an adulteress.[18] If tried before a tribunal both she and the young man would be stoned to death, but it was possible for her betrothed husband to issue a document of repudiation, and this, according to Matthew, was the course Joseph wished to take prior to the visitation by the angel.[19]

The most likely cultural context for both Matthew and Luke is Jewish Christian or mixed Gentile/Jewish-Christian circles rooted in Jewish tradition.[20] These readers would have known that the Roman Senate had declared Julius Caesar a god and his successor Augustus to be divi filius, the Son of God before he became a god himself on his death in AD 14; this remained the pattern for later emperors.[21] Imperial divinity was accompanied by suitable miraculous birth stories, with Augustus being fathered by the god Apollo while his human mother slept, and her human husband being granted a dream in which he saw the sun rise from her womb, and inscriptions even described the news of the divine imperial birth as evangelia, the gospel.[22] The virgin birth of Jesus was thus a direct challenge to a central claim of Roman imperial theology, namely the divine conception and descent of the emperors.[23]

Matthew's genealogy, tracing Jesus's Davidic descent, was intended for Jews, while his virgin birth story was intended for a Greco-Roman audience familiar with virgin birth stories and stories of women impregnated by gods.[24] The ancient world had no understanding that male semen and female ovum were both needed to form a fetus; instead they thought that the male contribution in reproduction consisted of some sort of formative or generative principle, while Mary's bodily fluids would provide all the matter that was needed for Jesus's bodily form, including his male sex.[4] This cultural milieu was conducive to miraculous birth stories – they were common in biblical tradition going back to Abraham and Sarah (and the conception of Isaac).[5]

Such stories are less frequent in Judaism, but there too there was a widespread belief in angels and divine intervention in births.[7] Theologically, the two accounts mark the moment when Jesus becomes the Son of God, i.e., at his birth, in distinction to Mark, for whom the Sonship dates from Jesus's baptism,[Mark 1:9–13] and Paul and the pre-Pauline Christians for whom Jesus becomes the Son only at the Resurrection or even the Second Coming.[25]

Tales of virgin birth and the impregnation of mortal women by deities were well known in the 1st-century Greco-Roman world,[6] and Second Temple Jewish works were also capable of producing accounts of the appearances of angels and miraculous births for ancient heroes such as Melchizedek, Noah, and Moses.[7] Luke's virgin birth story is a standard plot from the Jewish scriptures, as for example in the annunciation scenes for Isaac and for Samson, in which an angel appears and causes apprehension, the angel gives reassurance and announces the coming birth, the mother raises an objection, and the angel gives a sign.[26] Nevertheless, "plausible sources that tell of virgin birth in areas convincingly close to the gospels' own probable origins have proven extremely hard to demonstrate".[27] Similarly, while it is widely accepted that there is a connection with Zoroastrian (Persian) sources underlying Matthew's story of the Magi (the wise men from the East) and the Star of Bethlehem, a wider claim that Zoroastrianism formed the background to the infancy narratives has not achieved acceptance.[27]

Historicity and sources of the narratives

| Part of a series on |

|

|

The modern scholarly consensus is that the doctrine of the virgin birth rests on very slender historical foundations.[3] Both Matthew and Luke are late and anonymous compositions dating from the period AD 80–100.[28] The earliest Christian writings, the Pauline epistles, do not contain any mention of a virgin birth and assume Jesus's full humanity, stating that he was "born of a woman" like any other human being and "born under the law" like any Jew.[29] In the Gospel of Mark, dating from around AD 70, we read of Jesus saying that "prophets are not without honour, except in their home town, and among their own kin, and in their own house" – Mark 6:4, which suggests that Mark was not aware of any tradition of special circumstances surrounding Jesus' birth, and while the author of the gospel of John is confident that Jesus is more than human he makes no reference to a virgin birth to prove his point.[30] John in fact refers twice to Jesus as the "son of Joseph," the first time from the lips of the disciple Philip ("We have found him about whom Moses in the law and also the prophets wrote, Jesus, son of Joseph from Nazareth" – John 1:45), the second from the unbelieving Jews ("Is this not Jesus, the son of Joseph, whose mother and father we know?" – John 6:42).[31] These quotations, incidentally, are in direct opposition to the suggestion that Jesus was, or was believed to be, illegitimate: Philip and the Jews know that Jesus had a human father, and that father was Joseph.[32]

This raises the question of where the authors of Matthew and Luke found their stories. It is almost certain that neither was the work of an eyewitness.[33][34] In view of the many inconsistencies between them neither is likely to derive from the other, nor did they share a common source.[2] Raymond E. Brown suggested in 1973 that Joseph was the source of Matthew's account and Mary of Luke's, but modern scholars consider this "highly unlikely" given that the stories emerged so late.[35] It follows that the two narratives were created by the two writers, drawing on ideas in circulation at least a decade before the gospels were composed, to perhaps 65-75 or even earlier.[36]

Matthew presents the ministry of Jesus as largely the fulfilment of prophecies from the Book of Isaiah,[37] and Matthew 1:22-23, "All this took place to fulfill what had been spoken by the Lord through the prophet: "Look, the virgin shall conceive and bear a son...", is a reference to Isaiah 7:14, "...the Lord himself shall give you a sign: the maiden is with child and she will bear a son..."[38][39] But in the time of Jesus the Jews of Palestine no longer spoke Hebrew, Isaiah was translated into Greek,[37] and Matthew uses the Greek word parthenos, which does mean virgin, for the Hebrew almah, which scholars agree signifies a girl of childbearing age without reference to virginity.[38][39] This mistranslation gave the author of Matthew the opportunity to interpret Jesus as the prophesied Immanuel, God is with us, the divine representative on earth.[39]

Theology and development

Matthew and Luke use the virgin birth (or more accurately the divine conception that precedes it) to mark the moment when Jesus becomes the Son of God.[25] This was a notable development over Mark, for whom the Sonship dates from Jesus's baptism, Mark 1:9–13 and the earlier Christianity of Paul and the pre-Pauline Christians for whom Jesus becomes the Son at the Resurrection or even the Second Coming.[25] The Ebionites, a Jewish Christian sect, saw Jesus as fully human, rejected the virgin birth, and preferred to translate almah as "young woman".[40] The 2nd century gnostic theologian Marcion likewise rejected the virgin birth, but regarded Jesus as descended fully formed from heaven and having only the appearance of humanity.[41] By about AD 180 Jews were telling how Jesus had been illegitimately conceived by a Roman soldier named Pantera or Pandera, whose name is likely a pun on parthenos, virgin.[42] The story was still current in the Middle Ages in satirical parody of the Christian gospels called the Toledot Yeshu.[43][44] The Toledot Yeshu contains no historical facts, and was probably created as a tool for warding off conversions to Christianity.[43]

The virgin birth was subsequently accepted by Christians as the proof of the divinity of Jesus, but its rebuttal during and after the 18th century European Enlightenment led some to redefine it as mythical, while others reaffirmed it in dogmatic terms.[45] This division remains in place, although some national synods of the Catholic Church have replaced a biological understanding with the idea of "theological truth", and some evangelical theologians hold it to be marginal rather than indispensable to the Christian faith.[45]

Celebrations and devotions

Christians celebrate the conception of Jesus on 25 March and his birth on 25 December.[46] (These dates are traditional; no one knows for certain when Jesus was born.) The Magnificat, based on Luke 1:46-55 is one of four well known Gospel canticles: the Benedictus and the Magnificat in the first chapter, and the Gloria in Excelsis and the Nunc dimittis in the second chapter of Luke, which are now an integral part of the Christian liturgical tradition.[47] The Annunciation became an element of Marian devotions in medieval times, and by the 13th century direct references to it were widespread in French lyrics.[48] The Eastern Orthodox Church uses the title "Ever Virgin Mary" as a key element of its Marian veneration, and as part of the Akathists hymns to Mary which are an integral part of its liturgy.[49]

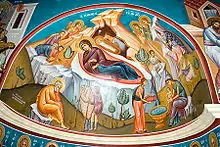

The doctrine is often represented in Christian art in terms of the annunciation to Mary by the Archangel Gabriel that she would conceive a child to be born the Son of God, and in Nativity scenes that include the figure of Salome. The Annunciation is one of the most frequently depicted scenes in Western art.[50] Annunciation scenes also amount to the most frequent appearances of Gabriel in medieval art.[51] The depiction of Joseph turning away in some Nativity scenes is a discreet reference to the fatherhood of the Holy Spirit, and the virgin birth.[52]

In Islam

The Quran acknowledges the virgin birth of Jesus while denying the Trinitarian implications of the gospel story (Jesus is a messenger of God but also a human being and not the Second Person of the Christian Trinity).[53] In surah 19 (Surah Maryam), the virgin Mary conceives and gives birth to Jesus, and when her people slander her, Mary does not respond except by pointing to her newborn son, Jesus, who defends his mother by miraculously speaking.[54] The Islamic view holds that Jesus was God's word which he directed to Mary and a spirit created by him, moreover Jesus was supported by the Holy Spirit.[55] The Quran follows the apocryphal gospels, and especially in the Protoevangelium of James, in their accounts of the miraculous births of both Mary and her son Jesus.[56] Surah 3:35–36, for example, follows the Protoevangelium closely when describing how the pregnant "wife of Imran" (that is, Mary's mother Anne) dedicates her unborn child to God, Mary's secluded upbringing within the Temple, and the angels who bring her food.[57]

Gallery

Holy Doors, Saint Catherine's Monastery on Mount Sinai in Egypt, 12th century

Holy Doors, Saint Catherine's Monastery on Mount Sinai in Egypt, 12th century Sandro Botticelli (1489–90)

Sandro Botticelli (1489–90) Mikhail Nesterov, Russia, 19th century

Mikhail Nesterov, Russia, 19th century Eastern Orthodox Nativity depiction little changed in more than a millennium

Eastern Orthodox Nativity depiction little changed in more than a millennium Giotto (1267–1337): Nativity with an uninvolved Joseph but without Salome

Giotto (1267–1337): Nativity with an uninvolved Joseph but without Salome Medieval miniature of the Nativity, c. 1350

Medieval miniature of the Nativity, c. 1350

See also

- Adoptionism

- Almah

- Christology

- Denial of the virgin birth of Jesus

- Immaculate Conception of Mary

- Incarnation (Christianity)

- Isaiah 7:14

- Perpetual virginity of Mary

- Parthenogenesis

References

Citations

- Carrigan 2000, p. 1359.

- Hurtado 2005, p. 318.

- Bruner 2004, p. 37.

- Lincoln 2013, p. 195–196, 258.

- Schowalter 1993, p. 790.

- Lachs 1987, p. 6.

- Casey 1991, p. 152.

- Ware 1993, p. unpaginated.

- Barclay 1998, p. 55.

- Robinson 2009, p. 111.

- Lincoln 2013, p. 99.

- Morris 1992, p. 31–32.

- Carroll 2012, p. 39.

- Zervos 2019, p. 78.

- BeDuhn 2015, p. 170.

- Dunn 2003, p. 341-343.

- Vermes 2006a, p. 216.

- Vermes 2006b, p. 72.

- Vermes 2006b, p. 73.

- Hurtado 2005, p. 328.

- Hornblower & Spawforth 2014, p. 688.

- Borg 2011, p. 41-42.

- Borg 2011, p. 41.

- Lachs 1987, p. 5-6.

- Loewe 1996, p. 184.

- Kodell 1992, p. 939.

- Welburn 2008, p. 2.

- Fredriksen 2008, p. 7.

- Lincoln 2013, p. 21.

- Lincoln 2013, p. 23.

- Lincoln 2013, p. 24.

- Lincoln 2013, p. 29.

- Boring & Craddock 2009, p. 12.

- Reddish 2011, p. 13.

- Lincoln 2013, p. 144.

- Hurtado 2005, p. 318–319, 325.

- Barker 2001, p. 490.

- Sweeney 1996, p. 161.

- Saldarini 2001, p. 1007.

- Paget 2010, p. 351.

- Hayes 2017, p. 152 fn.153.

- Voorst 2000, p. 117.

- Cook 2011, p. unpaginated.

- Evans 1998, p. 450.

- Kärkkäinen 2009, p. 175.

- Nothaft 2014, p. 564.

- Simpler 1990, p. 396.

- O'Sullivan 2005, p. 14–15.

- Peltomaa 2001, p. 127.

- Guiley 2004, p. 183.

- Ross 1996, p. 99.

- Grabar 1968, p. 130.

- Hulmes 1993, p. 640.

- Zebiri 2000.

- Saritoprak 2014, pp. 3, 6.

- Bell 2012, p. 110.

- Reynolds 2018, p. 55–56.

Bibliography

- Akyol, Mustafa (2017). The Islamic Jesus. St. Martin's Publishing Group. ISBN 9781250088703.

- Barclay, William (1998). The Apostles' Creed. Westminster John Knox Press. ISBN 9781250088703.

- Barker, Margaret (2001). "Isaiah". In Dunn, James D.G.; Rogerson, John (eds.). Eerdmans Commentary on the Bible. Eerdmans. ISBN 9780802837110.

- BeDuhn, Jason (2015). "The New Marcion" (PDF). Forum. 3 (Fall 2015): 163–179.

- Bell, Richard (2012). The Origin of Islam in Its Christian Environment. Routledge. ISBN 9781136260674.

- Borg, Marcus (2011). Jesus. SPCK. ISBN 9780281066063.

- Brown, Raymond E. (1973). The Virginal Conception and Bodily Resurrection of Jesus. Paulist Press. ISBN 978-0809117680.

- Brown, Raymond E. (1999). The Birth of the Messiah: A Commentary on the Infancy Narratives in the Gospels of Matthew and Luke. Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0300140088.

- Boring, M. Eugene; Craddock, Fred B. (2009). The People's New Testament Commentary. Westminster John Knox. ISBN 9780664235925.

- Bruner, Frederick (2004). Matthew 1-12. Eerdmans. ISBN 9780802811189.

- Carrigan, Henry L. (2000), "Virgin Birth", in Freedman, David Noel; Myers, Allen C. (eds.), Eerdmans Dictionary of the Bible, Eerdmans, ISBN 9789053565032

- Carroll, John T. (2000). "Eschatology". In Freedman, David Noel; Myers, Allen C. (eds.). Eerdmans Dictionary of the Bible. Eerdmans. ISBN 9789053565032.

- Carroll, John T. (2012). Luke: A Commentary. Westminster John Knox Press. ISBN 978-0664221065.

- Casey, Maurice (1991). From Jewish Prophet to Gentile God: The Origins and Development of New Testament Christology. Westminster John Knox Press. ISBN 9780664227654.

- Childs, Brevard S (2001). Isaiah. Westminster John Knox Press. ISBN 978-0664221430.

- Chouinard, Larry (1997), Matthew, College Press, ISBN 978-0899006284

- Collinge, William J. (2012). Historical Dictionary of Catholicism. Scarecrow Press. ISBN 9780810879799.

- Coyle, Kathleen (1996), Mary in the Christian Tradition (revised ed.), Gracewing Publishing, ISBN 978-0852443804

- Cook, Michael J. (2011), "Jewish Perspectives on Jesus", in Burkett, Delbert (ed.), The Blackwell Companion to Jesus, John Wiley & Sons, ISBN 9781444351750

- Davidson, John (2005). The Gospel Of Jesus: In Search Of His Original Teachings. Clear Press. ISBN 978-1904555148.

- Deiss, Lucien (1996). Joseph, Mary, Jesus. Liturgical Press. ISBN 978-0814622551.

- Dorman, T.M. (1995). "Virgin Birth". In Bromiley, Geoffrey W. (ed.). International Standard Bible Encyclopedia: Q-Z. Eerdmans. ISBN 978-0802837844.

- Dunn, James D.G. (2003). Jesus Remembered: Christianity in the Making, Volume 1. Eerdmans. ISBN 9780802839312.

- Erskine, Andrew (2009). A Companion to the Hellenistic World. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 9781405154413.

- Evans, Craig (1998), "Jesus in non-Christian Sources", in Chilton, Bruce; Evans, Craig (eds.), Studying the Historical Jesus: Evaluations of the State of Current Research, BRILL, ISBN 9004111425

- France, R.T. (2007). The Gospel of Matthew. Eerdmans. ISBN 978-0802825018.

- Fredriksen, Paula (2008). From Jesus to Christ: The Origins of the New Testament Images of Jesus. Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0300164107.

- Grabar, André (1968). Christian Iconography: A Study of Its Origins. Princeton University Press. ISBN 9780710062376.

- Gregg, D. Larry (2000). "Docetism". In Freedman, David Noel; Myers, Allen C. (eds.). Eerdmans Dictionary of the Bible. Eerdmans. ISBN 9789053565032.

- Guiley, Rosemary (2004). The Encyclopedia of Angels. New York: Facts on File. ISBN 0-8160-5023-6.

- Hayes, Andrew (2017). Justin against Marcion: Defining the Christian Philosophy. Fortress Press.

- Hendrickson, Peter A.; Jenson, Bradley C.; Lundell, Randi H. (2015). Luther and Bach on the Magnificat. Wipf and Stock. ISBN 9781625641205.

- Hornblower, Simon; Spawnforth, Antony (2014). The Oxford Companion to Classical Civilization. Oxford University Press.

- Hulmes, Edward (1993), "Quran and the Bible, The", in Metzger, Bruce M.; Coogan, Michael David (eds.), The Oxford Companion to the Bible, Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0-19-974391-9

- Hurtado, Larry (2005). Lord Jesus Christ: Devotion to Jesus in Earliest Christianity. Eerdmans. ISBN 9780802831675.

- Kärkkäinen, V.-N (2009), "Christology", in Dyrness, William A.; Kärkkäinen, Veli-Matti (eds.), Global Dictionary of Theology, InterVarsity Press, ISBN 9780830878116

- Kodell, Jerome (1992). "Luke". In Karris, Robert J. (ed.). The Collegeville Bible Commentary: New Testament, NAB. Liturgical Press. ISBN 978-0814622117.

- Koester, Helmut (2000). Introduction to the New Testament: History and literature of early Christianity. Vol. 2. Walter de Gruyter. ISBN 9783110149708.

- Kugler, Robert; Hartin, Patrick (2009). An Introduction to the Bible. Eerdmans. ISBN 9780802846365.

- Lachs, Samuel T. (1987). A Rabbinic Commentary of the New Testament: the Gospels of Matthew, Mark and Luke. KTAV Publishing House. ISBN 978-0881250893.

- Lincoln, Andrew (2013). Born of a Virgin?. Eerdmans. ISBN 978-0802869258.

- Loewe, William P. (1996). The College Student's Introduction to Christology. Liturgical Press. ISBN 9780814650189.

- Marsh, Clive; Moyise, Steve (2006). Jesus and the Gospels. A&C Black. ISBN 978-0567040732.

- Marthaler, Berard L. (2007). The Creed: The Apostolic Faith in Contemporary Theology. Twenty-Third Publications. ISBN 9780896225374.

- McGuckin, John Anthony (2004). The Westminster Handbook to Patristic Theology. Westminster John Knox Press. ISBN 9780664223960.

- Miller, John W. (2008). "The Miracle of Christ's Birth". In Ellens, J. Harold (ed.). Miracles. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 978-0275997236.

- Morris, Leon (1992). The Gospel According to Matthew. Eerdmans. ISBN 978-0851113388.

- Nothaft, C. Philipp E. (2014). Medieval Latin Christian Texts on the Jewish Calendar: A Study with Five Editions and Translations. Leiden: Brill. ISBN 9789004274129.

- O'Sullivan, Daniel E. (2005). Marian devotion in thirteenth-century French lyric. University of Toronto Press. ISBN 0802038859.

- Paget, James Carleton (2010). Jews, Christians and Jewish Christians in Antiquity. Mohr Siebeck. ISBN 9783161503122.

- Reddish, Mitchell (2011). An Introduction to The Gospels. Abingdon Press. ISBN 9781426750083.

- Peltomaa, Leena Mari (2001). The image of the Virgin Mary in the Akathistos hymn. Brill. ISBN 9004120882.

- Reynolds, Gabriel Said (2018). The Qur'an and the Bible: Text and Commentary. Yale University Press. ISBN 9780300181326.

- Robinson, Bernard P. (2009). "Matthew's Nativity Stories". In Corley, Jeremy (ed.). New Perspectives on the Nativity. Bloomsbury. ISBN 9780567613790.

- Ross, Leslie (1996). Medieval Art: A Topical Dictionary. Greenwood Press. ISBN 9780313293290.

- Saldarini, Anthony J. (2001). "Matthew". In Dunn, James D.G.; Rogerson, John (eds.). Eerdmans Commentary on the Bible. Eerdmans. ISBN 9780802837110.

- Saritoprak, Zeki (2014). Islam's Jesus. Tampa: University Press of Florida. ISBN 978-0-8130-4940-3.

- Satlow, Michael L. (2018). Jewish Marriage in Antiquity. Princeton University Press. ISBN 9780691187495.

- Sawyer, W. Thomas (1990). "Mary". In Mills, Watson E.; Bullard, Roger Aubrey (eds.). Mercer Dictionary of the Bible. Mercer University Press. ISBN 978-0865543737.

- Schowalter, Daniel N. (1993). "Virgin Birth of Christ". In Metzger, B.M.; Coogan, D. (eds.). The Oxford Companion to the Bible. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780199743919.

- Simpler, Steven (1990). "Hymn". In Mills, Watson E.; Bullard, Roger Aubrey (eds.). Mercer Dictionary of the Bible. Mercer University Press. ISBN 9780865543737.

- Sweeney, Marvin A (1996). Isaiah 1–39: with an introduction to prophetic literature. Eerdmans. ISBN 978-0802841001.

- Turner, David L. (2008). Matthew. Baker. ISBN 978-0-8010-2684-3.

- Tyson, Joseph B. (2006). Marcion and Luke-Acts: A Defining Struggle. University of South Carolina Press. ISBN 9781570036507.

- Vermes, Geza (2006a). Who's Who in the Age of Jesus. Penguin UK. ISBN 9780141937557.

- Vermes, Geza (2006b). The Nativity: History and Legend. Penguin UK. ISBN 9780141912615.

- Voorst, Robert van (2000). Jesus Outside the New Testament. Eerdmans. ISBN 9780802843685.

- Wahlde, Urban von (2015). Gnosticism, Docetism, and the Judaisms of the First Century. Bloomsbury. ISBN 9780567656599.

- Ware, Timothy (1993). The Orthodox Church: An Introduction to Eastern Christianity. Penguin. ISBN 9780141925004.

- Weaver, Rebeccah H. (2008), "Jesus in early Christianity", in Benedetto, Robert; Duke, James O (eds.), The New Westminster Dictionary of Church History: The early, medieval, and Reformation eras, Westminster John Knox Press, ISBN 978-0664224165

- Welburn, Andrew J. (2008). From a Virgin Womb: The "Apocalypse of Adam" and the Virgin Birth. BRILL. ISBN 9789004163768.

- Wilson, Frank E. (1989). Faith and Practice. Harrisburg, PA: Church Publishing, Inc. ISBN 9780819224576.

- Zebiri, Kate (March 2000). "Contemporary Muslim Understanding of the Miracles of Jesus". The Muslim World. 90 (1–2): 71–90. doi:10.1111/j.1478-1913.2000.tb03682.x.

- Zervos, George (2019). The Protevangelium of James. Bloomsbury Academic. p. 79. ISBN 9780567053169.

.jpg.webp)

.jpg.webp)