Voting

Voting is a method for a group, such as a meeting or an electorate, in order to make a collective decision or express an opinion usually following discussions, debates or election campaigns. Democracies elect holders of high office by voting. Residents of a place represented by an elected official are called "constituents", and those constituents who cast a ballot for their chosen candidate are called "voters". There are different systems for collecting votes, but while many of the systems used in decision-making can also be used as electoral systems, any which cater for proportional representation can only be used in elections.

| Part of the Politics series |

| Voting |

|---|

|

|

In smaller organizations, voting can occur in different ways. Formally via ballot to elect others for example within a workplace, to elect members of political associations or to choose roles for others. Informally voting could occur as a spoken agreement or as a verbal gesture like a raised hand or electronically.

In politics

In a democracy, a government is chosen by voting in an election: a way for an electorate to elect, i.e., choose, among several candidates for rule.[1] However, more than likely, elections will be between two opposing parties. These two will be the most established and the most popular. For example, in the US the competition is between the Republicans and the Democrats. In an indirect democracy voting is the method by which the person elected (in charge) represents their policies and party, whilst making decisions, with regards to other authorities. For example, in the UK the prime minister has to make decisions with regards to the House Of Commons and House Of Lords. Direct democracy, is the complete opposite, the person elected, has more independent control and does not need to get policies passed throughout the government.

In retrospect, a majority vote is when the mass of individual's vote for the same person. However, whilst each individuals choice for or against, does count, a lot of countries use geographic measures to decide who wins. For example, in the UK the person with the most constituencies wins, but they may not always have the most individual votes. Other countries who have liberal democracies, may use a secret ballot, hoping to prevent individuals from becoming influenced by other people and to protect their political privacy. The objective for secret ballots, is to try and get the most authentic outcome. A reasoning behind why this way of voting may capture a better result, is mainly to do with social influence. People may be obligated to vote for certain parties due to feeling pressured, having a lack of knowledge, or siding with what they think may be the majority, purely to fit in. Therefore, not only will the people feel more protected, they may also be able to vote for who they actually think will be the best representative.

Voting often takes place at a polling station; but can also be done by electronic voting systems, which has been used in India, Brazil and the Philippines. It is voluntary in some countries, like the UK, but it may be compulsory in others, such as Australia.

Due to countries having different rules about whether or not voting is compulsory, statistics showing how voting has changed will differ.

Decision-making systems

When making a decision, those concerned seek one outcome: a majority opinion for a single decision or a single prioritisation. There are several ways in which voters and/or elected representatives may seek to identify that majority opinion. There is the simple, weighted or consociational majority vote. There are other multi-option procedures as well; these include two-round voting, the alternative vote AV, (which is also known as instant run-off voting IRV, and the single transferable vote STV), approval voting, a Borda Count BC, the Modified Borda Count MBC, and the Condorcet rule, nearly all of which are also used as electoral systems. They are outlined below.

Electoral systems

There are rather more electoral systems, because of proportional representation, PR. Those concerned might want to select just one person, or maybe a committee, or maybe an entire parliament. In electing a president, there is usually just one winner, although the original system in the United States also elected the runner-up as a vice-president. In electing a parliament, either each of many small constituencies can elect a single representative, as in Britain; or each of quite a few multi-member constituencies may elect a few representatives, as in Ireland; or the entire country can be treated as the one constituency, as in The Netherlands.

Different voting systems use different types of votes. Plurality voting does not require the winner to achieve a voting majority or more than fifty per cent of the total votes cast. In a voting system that uses a single vote per race, when more than two candidates run, the winner may commonly have less than fifty per cent of the vote.

A side effect of a single vote per race is vote splitting, which tends to elect candidates that do not support centrism, and tends to produce a two-party system. One of many other procedures to a single-vote system is approval voting.

To understand why a single vote per race tends to favour less centric candidates, consider a simple lab experiment where students in a class vote for their favourite marble. If five marbles are assigned names and are placed "up for election", and if three of them are green, one is red, and one is blue, then a green marble will rarely win the election. The reason is that the three green marbles will split the votes of those who prefer green. In fact, in this analogy, the only way that a green marble is likely to win is if more than sixty per cent of the voters prefer green. If the same percentage of people prefer green as those who prefer red and blue, that is to say, if 33 per cent of the voters prefer green, 33 per cent prefer blue, and 33 per cent prefer red, then each green marble will only get eleven per cent of the vote, while the red and blue marbles will each get 33 per cent, putting the green marbles at a serious disadvantage. If the experiment is repeated with other colours, the colour that is in the majority will still rarely win. In other words, from a purely mathematical perspective, a single-vote system tends to favour a winner that is different from the majority.

With approval voting, voters are encouraged to vote for as many candidates as they approve of, so the winner is much more likely to be any one of the five marbles because people who prefer green will be able to vote for every one of the green marbles.

A development on the 'single vote' system is to have two-round elections, or repeat first-past-the-post. This system is most common around the world. In most cases, the winner must receive a majority, which is more than half.[2] and if no candidate obtains a majority at the first round, then the two candidates with the largest plurality are selected for the second round. Variants exist on these two points: the requirement for being elected at the first round is sometimes less than 50%, and the rules for participation in the runoff may vary.

A third procedure is a single round instant-runoff voting system (Also referred to as Alternative vote or Single Transferable Vote or Preferential voting) as used in some elections in Australia, the United States and, in its PR format, in Ireland. Voters rank each candidate in order of preference (1,2,3,4 etc.). Votes are distributed to each candidate according to the preferences allocated. If no single candidate has 50% of the vote, then the candidate with the fewest votes is excluded and their votes redistributed according to the voter's nominated order of preference. The process repeating itself until a candidate has 50% or more votes. The system is designed to produce the same result as an exhaustive ballot but using only a single round of voting.

In its PR format, PR-STV, in say a four-seater constituency, every candidate with a quota of 1st preferences will be elected. A quota in this instance is 20% + 1 of the valid vote. If a candidate has more than a quota, his/her surplus will be distributed to the other candidates, in proportion to all of that candidate's 2nd preferences. If there are still candidates to be elected, the least popular is eliminated, as above in AV or IRV, and the process continues until four candidates have reached a quota.

In the Quota Borda System, QBS, Emerson P (2012)[3] the voters also cast their preferences, 1,2,3,4... as they wish. In the analysis, all 1st preferences are counted; all 2nd preferences are counted; and after these preferences have been translated into points as per the rules of an MBC, the candidates' points are also counted. Seats are awarded to any candidates with a quota of 1st preferences; to any pair of candidates with two quotas of 1st/2nd preferences; and if seats are still to be filled, to those candidates with the highest MBC scores.

In a voting system that uses multiple votes, the voter can vote for any subset of the alternatives. So, a voter might vote for Alice, Bob, and Charlie, rejecting Daniel and Emily. Approval voting uses such multiple votes.

In a voting system that uses a ranked vote, the voter has to rank the alternatives in order of preference. For example, they might vote for Bob in the first place, then Emily, then Alice, then Daniel, and finally Charlie. Ranked voting systems, such as those used in Australia and Ireland, use a ranked vote.

In a voting system that uses a scored vote (or range vote), the voter gives each alternative a number between one and ten (the upper and lower bounds may vary). See cardinal voting systems.

Some "multiple-winner" systems such as the Single Non-Transferable Vote, SNTV, used in Afghanistan may have a single vote or one vote per elector per available position. In such a case the elector could vote for Bob and Charlie on a ballot with two votes. These types of systems can use ranked or unranked voting and are often used for at-large positions such as on some city councils.

Finally, the Condorcet rule, used (if at all) in decision-making. The voters or elected representatives cast their preferences on one, some or all options, 1,2,3,4... as in PR-STV or QBS. In the analysis, option A is compared to option B, and if A is more popular than B, then A wins this pairing. Next, A is compared with option C, then D, and so on. Likewise, B is compared with C, with D etc. The option which wins the most pairings, (if there is one), is the Condorcet winner.

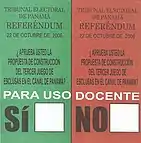

Referendums

When the citizens of a country are invited to vote, it is for an election. However, people can also vote in referendums and initiatives. Since the end of the eighteenth century, more than five hundred national referendums (including initiatives) were organized in the world; among them, more than three hundred were held in Switzerland.[4] Australia ranked second with dozens of referendums.

Most referendums are binary. The first multi-option referendum was held in New Zealand in 1894, and most of them are conducted under a two-round system. New Zealand had a five-option referendum in 1992, while Guam had a six-option plebiscite in 1982, which also offered a blank option, in case some voters wanted to (campaign and) vote for a seventh option.

Fair voting

Results may lead at best to confusion, at worst to violence and even civil war, in the case of political rivals. Many alternatives may fall in the latitude of indifference—they are neither accepted nor rejected. Avoiding the choice that most people strongly reject may sometimes be as important as choosing the one they most favour.

There are social choice theory definitions of seemingly reasonable criteria that are a measure of the fairness of certain aspects of voting, including non-dictatorship, unrestricted domain, non-imposition, Pareto efficiency, and independence of irrelevant alternatives but Arrow's impossibility theorem states that no voting system can meet all these standards.

To ensure fair voting and preventing the misuse of the microblogging platform, Twitter announced adding a feature for users to report content that misleads voters. This announcement came when general elections are going to be held in India and some other countries.[5]

Negative voting

Negative voting allows a vote that expresses disapproval of a candidate. For explanatory purposes, consider a hypothetical voting system that uses negative voting. In this system, one vote is allowed, with the choice of either for a candidate or against a candidate. Each positive vote adds one to a candidate's overall total, while a negative vote subtracts one, arriving at a net favorability. The candidate with the highest net favorability is the winner. Note that not only is a negative total possible, but also, a candidate may even be elected with 0 votes if enough negative votes are cast against their opponents.

Under this implementation, negative voting is no different from a positive voting system, when only two candidates are on the ballot. However, in the case of three or more candidates, each negative vote for a candidate counts positively towards all of the other candidates.

Consider the following example:

Three candidates are running for the same seat. Two hypothetical election results are given, contrasting positive and negative voting. Both polling accuracy and voter turnout are assumed to be 100 per cent.

| Candidate | Party | Polling |

|---|---|---|

| A | Party 1 | 40% |

| B | Party 2 | 30% |

| C | Party 3 | 30% |

| Candidates | A voters | B voters | C voters | Net total |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | +40 | +15 | 0 | +55 |

| B | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| C | 0 | +15 | +30 | +45 |

| Candidates | A voters | B voters | C voters | Net total |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | +40 | -15 | -30 | -5 |

| B | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| C | 0 | -15 | 0 | -15 |

Election results with positive voting:

A-voters, with the clear advantage of 40%, logically vote for Candidate A. B-voters, unconfident of their candidate's chances, split their votes exactly in half, giving both Candidates A and C 15% each. C-voters, also logically vote for their candidate. A is the winner with 55%, C at 45%, and B 0%.

Election results with negative voting:

A-voters again, with the clear advantage of 40%, logically vote for Candidate A. B-voters, split exactly in half. Each B-voter decides to vote negatively against their least favourite candidate, with the reasoning that this negative vote allows them to express approval for the two other candidates. C-voters also decide to vote negatively against Candidate A, reasoning along similar lines. Candidate B is the winner with 0 votes. Enough negative votes were cast against Candidate B's opponents, resulting in negative totals. Candidate A, despite having polled at 40%, winds up with -5%, offset due to the aggregate 45% of negative votes cast by B and C voters. Candidate C ends up with -15%.

Proxy voting

Proxy voting is the type of voting where a registered citizen who can vote passes on his or her vote to a different voter or electorate legitimately.

Anti-voting

In South Africa, there is a strong presence of anti-voting campaigns by poor citizens. They make the structural argument that no political party truly represents them. For instance, this resulted in the "No Land! No House! No Vote!" A campaign that becomes very prominent each time the country holds elections.[6][7] The campaign is prominent among three of South Africa's largest social movements: the Western Cape Anti-Eviction Campaign, Abahlali baseMjondolo, and the Landless Peoples Movement.

Other social movements in other parts of the world also have similar campaigns or non-voting preferences. These include the Zapatista Army of National Liberation and various anarchist-oriented movements.

It is possible to make a blank vote, carrying out the act of voting, which may be compulsory, without selecting any candidate or option, often as an act of protest. In some jurisdictions, there is an official none of the above option and it is counted as a valid vote. Usually, blank and null votes are counted (together or separately) but are not considered valid.

Voting and information

Modern political science has questioned whether average citizens have sufficient political information to cast meaningful votes. A series of studies coming out of the University of Michigan in the 1950s and 1960s argued that voters lack a basic understanding of current issues, the liberal–conservative ideological dimension, and the relative ideological dilemma.[8]

Studies from other institutions have suggested that the physical appearance of candidates is a criterion upon which voters base their decision.[9][10]

Religious views

Christadelphians, Jehovah's Witnesses, Old Order Amish, Rastafarians, the Assemblies of Yahweh, and some other religious groups, have a policy of not participating in politics through voting.[11][12] Rabbis from all Jewish denominations encourage voting; some even consider it a religious obligation.[13]

Meetings and gatherings

Whenever several people who do not all agree need to make some decision, voting is a very common way of reaching a decision peacefully. The right to vote is usually restricted to certain people. Members of a society or club, or shareholders of a company, but not outsiders, may elect its officers, or adopt or change its rules, in a similar way to the election of people to official positions. A panel of judges, either formal judicial authorities or judges of the competition, may decide by voting. A group of friends or members of a family may decide which film to see by voting. The method of voting can range from formal submission of written votes, through show of hands, voice voting or audience response systems, to informally noting which outcome seems to be preferred by more people.

Voting basis

According to Robert's Rules of Order, a widely used guide to parliamentary procedure, the bases for determining the voting result consist of two elements: (1) the percentage of votes that are required for a proposal to be adopted or for a candidate to be elected (e.g. more than half, two-thirds, three-quarters, etc.); and (2) the set of members to which the proportion applies (e.g. the members present and voting, the members present, the entire membership of the organization, the entire electorate, etc.).[14] An example is a majority vote of the members present and voting.

The voting result could also be determined using a plurality, or the most votes among the choices.[15]

In addition, a decision could be made without a formal vote by using unanimous consent.[16]

| Part of the Politics series |

| Electoral systems |

|---|

.svg.png.webp) |

|

|

A voting method is the way in which people cast their votes in an election or referendum. There are several different methods in use around the world.

Voting methods in deliberative assemblies

Deliberative assemblies—bodies that use parliamentary procedure to arrive at decisions—use several methods of voting on motions (formal proposal by a member or members of a deliberative assembly that the assembly takes certain action). The regular methods of voting in such bodies are a voice vote, a rising vote, and a show of hands. Additional forms of voting include a recorded vote and balloting. The assembly could decide on the voting method by adopting a motion on it. Different legislatures may have their voting methods.

Voting methods

Paper-based methods

The most common voting method uses paper ballots on which voters mark their preferences. This may involve marking their support for a candidate or party listed on the ballot, or a write-in, where they write out the name of their preferred candidate if it is not listed.

An alternative paper-based system known as ballot letters is used in Israel, where polling booths contain a tray with ballots for each party contesting the elections; the ballots are marked with the letter(s) assigned to that party. Voters are given an envelope into which they put the ballot of the party they wish to vote for, before placing the envelope in the ballot box. The same system is also implemented in Latvia.

Machine voting

Machine voting uses voting machines, which may be manual (e.g. lever machines) or electronic.[17]

Online voting

In some countries, people are allowed to vote online. Estonia was one of the first countries to use online voting: it was first used in the 2005 local elections.[18]

Postal voting

Many countries allow postal voting, where voters are sent a ballot and return it by post.

Open ballot

In contrast to a secret ballot, an open ballot takes place in public and is commonly done by a show of hands. An example is the Landsgemeinde system in Switzerland, which is still in use in the cantons of Appenzell Innerrhoden, Glarus, Grisons, and Schwyz.

Other methods

In The Gambia, voting is carried out using marbles, a method introduced in 1965 to deal with illiteracy.[19] Polling stations contain metal drums painted in party colours and emblems with candidates' photos attached to them.[20][19] Voters are given a marble to place in the drum of their chosen candidate; when dropped into the drum, a bell sounds to register the vote. To avoid confusion, bicycles are banned near polling booths on election day.[19] If the marble is left on top of the drum rather than placed in it, the vote is deemed invalid.[21]

A similar system used in social clubs sees voters given a white ball to indicate support and a black ball to indicate opposition. This led to the coining of the term blackballing.

In person

Some votes are carried in person if all the people eligible to vote are present. This could be by a show of hands or keypad polling.

See also

- Cosmopolitan democracy

- Democratic mundialization

- Dollar voting

- Donuts

- Electoral fraud

- Electoral system

- Gerrymandering

- Mandate (politics)

- Ranked voting systems

- Opinion poll

- Political base

- Presidential election

- Proportional representation

- Psephology

- Redistricting

- Referendum

- Suffrage

- Voter turnout

- Voting bloc

- Voting methods in deliberative assemblies

- Voting system

- Right of expatriates to vote in their country of origin

- Vote splitting

References

- "Voting - GOV.UK". www.gov.uk. Retrieved 9 June 2018.

- Majority rule.

- From Majority Rule to Inclusive Politics. Heidelberg: Springer. p 80. ISBN 978-3-319-23499-1

- (in French) Bruno S. Frey et Claudia Frey Marti, Le bonheur. L'approche économique, Presses Polytechniques et Universitaires romandes, 2013 (ISBN 978-2-88915-010-6).

- "Twitter adds feature for users to report content that misleads voters". thehindubusinessline. 24 April 2019.

- "The 'No Land, No House, No Vote campaign still on for 2009". Abahlali baseMjondolo. 5 May 2005.

- "IndyMedia Presents: No Land! No House! No Vote!". Anti-Eviction Campaign. 12 December 2005. Archived from the original on 25 April 2009.

- Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. (Summary Archived 19 June 2019 at the Wayback Machine)

- Kesten C. Greene and J. Scott Armstrong and Randall J. Jones, Jr., and Malcolm Wright (2010). "Predicting Elections from Politicians' Faces" (PDF).

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Andreas Graefe & J. Scott Armstrong (2010). "Predicting Elections from Biographical Information about Candidates" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 5 November 2011. Retrieved 7 December 2011.

- Leibenluft, Jacob (28 June 2008). "Why Don't Jehovah's Witnesses Vote? Because they're representatives of God's heavenly kingdom". Slate.

- "Statement of Doctrine | Assemblies of Yahweh".

- "Ask the Rabbis // Voting." Moment Magazine. May–June 2016. 10 October 2016.

- Robert, Henry M.; et al. (2011). Robert's Rules of Order Newly Revised (11th ed.). Philadelphia, PA: Da Capo Press. p. 402. ISBN 978-0-306-82020-5.

- Robert 2011, pp. 404–405

- Robert 2011, p. 54

- 1198 not-read-how-vote-makes-cleaner-fairer-elections-making-their Illiterate voters: Making their mark The Economist, 5 April 2014

- Voting methods in Estonia: Statistics about Internet Voting in Estonia VVK

- Gambians vote with their marbles BBC News, 22 September 2006

- The Gambia vote a roll of the marbles The Telegraph, 29 November 2016

- Gambia election: Voters use marbles to choose president BBC News, 30 November 2016

External links

- A history of voting in the United States from the Smithsonian Institution.

- A New Nation Votes: American Elections Returns 1787-1825 Archived 25 July 2008 at the Wayback Machine

- Can I Vote?—a nonpartisan US resource for registering to vote and finding your polling place from the National Association of Secretaries of State.

- The Canadian Museum of Civilization — A History of the Vote in Canada

- Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 28 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 216–217. This contains a brief history of voting in Ancient Greece and Rome; see also Electoral system s.v. History.

- "Voting", CORE,

Open access research papers