Walmart

Walmart Inc. ( /ˈwɔːlmɑːrt/; formerly Wal-Mart Stores, Inc.) is an American multinational retail corporation that operates a chain of hypermarkets (also called supercenters), discount department stores, and grocery stores from the United States, headquartered in Bentonville, Arkansas.[10] The company was founded by Sam Walton in nearby Rogers, Arkansas in 1962 and incorporated under Delaware General Corporation Law on October 31, 1969. It also owns and operates Sam's Club retail warehouses.[11][12]

Logo since 2008 | |

Headquarters (“Home Office”) in December 2012 | |

| Formerly |

|

|---|---|

| Type | Public |

Traded as | |

| ISIN | US9311421039 |

| Industry | Retail |

| Predecessor | Walton's Five and Dime |

| Founded |

|

| Founder | Sam Walton |

| Headquarters | , U.S. |

Number of locations | 10,585 stores worldwide (July 31, 2022)[2][3][4] |

Area served | Worldwide |

Key people |

|

| Services |

|

| Revenue | |

| Total assets | |

| Total equity | |

| Owner | Walton family (50.85%)[6] |

Number of employees | 2,300,000 (Jan. 2022)[5] |

| Divisions |

|

| Subsidiaries | List of subsidiaries |

| Website | walmart.com |

| Footnotes / references [7][8][9] | |

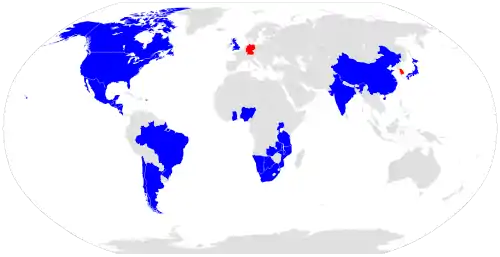

As of July 31, 2022, Walmart has 10,585 stores and clubs in 24 countries, operating under 46 different names.[2][3][4] The company operates under the name Walmart in the United States and Canada, as Walmart de México y Centroamérica in Mexico and Central America, and as Flipkart Wholesale in India. It has wholly owned operations in Chile, Canada, and South Africa. Since August 2018, Walmart held only a minority stake in Walmart Brasil, which was renamed Grupo Big in August 2019, with 20 percent of the company's shares, and private equity firm Advent International holding 80 percent ownership of the company. They eventually divested their shareholdings in Grupo Big to French retailer Carrefour, in transaction worth R$7 billion and completed on June 7, 2022.[13]

Walmart is the world's largest company by revenue, with about US$570 billion in annual revenue, according to the Fortune Global 500 list in May 2022. It is also the largest private employer in the world with 2.2 million employees. It is a publicly traded family-owned business, as the company is controlled by the Walton family. Sam Walton's heirs own over 50 percent of Walmart through both their holding company Walton Enterprises and their individual holdings.[14] Walmart was the largest United States grocery retailer in 2019, and 65 percent of Walmart's US$510.329 billion sales came from U.S. operations.[15][16]

Walmart was listed on the New York Stock Exchange in 1972. By 1988, it was the most profitable retailer in the U.S.,[17] and it had become the largest in terms of revenue by October 1989.[18] The company was originally geographically limited to the South and lower Midwest, but it had stores from coast to coast by the early 1990s. Sam's Club opened in New Jersey in November 1989, and the first California outlet opened in Lancaster, in July 1990. A Walmart in York, Pennsylvania, opened in October 1990, the first main store in the Northeast.[19]

Walmart's investments outside the U.S. have seen mixed results. Its operations and subsidiaries in Canada,[20] the United Kingdom (ASDA),[21] Central America, South America, and China are successful, but its ventures failed in Germany, Japan, and South Korea.[22][23][24]

History

1945–1969: Early history

In 1945, businessman and former J. C. Penney employee Sam Walton bought a branch of the Ben Franklin stores from the Butler Brothers.[25] His primary focus was selling products at low prices to get higher-volume sales at a lower profit margin, portraying it as a crusade for the consumer. He experienced setbacks because the lease price and branch purchase were unusually high, but he was able to find lower-cost suppliers than those used by other stores and was consequently able to undercut his competitors on pricing.[26] Sales increased 45 percent in his first year of ownership to US$105,000 in revenue, which increased to $140,000 the next year and $175,000 the year after that. Within the fifth year, the store was generating $250,000 in revenue. The lease then expired for the location and Walton was unable to reach an agreement for renewal, so he opened up a new store at 105 N. Main Street in Bentonville, naming it "Walton's Five and Dime".[26][27] That store is now the Walmart Museum.[28]

On July 2, 1962, Walton opened the first Wal-Mart Discount City store at 719 W. Walnut Street in Rogers, Arkansas. Its design was inspired by Ann & Hope, which Walton visited in 1961, as did Kmart founder Harry B. Cunningham.[29][30] The name came from FedMart, a chain of discount department stores founded by Sol Price in 1954, whom Walton was also inspired by. Walton stated that he liked the idea of calling his discount chain "Wal-Mart" because he "really liked Sol's FedMart name". The building is now occupied by a hardware store and an antiques mall, while the company's "Store #1" has since expanded to a Supercenter several blocks west at 2110 W. Walnut Street. Within its first five years, the company expanded to 18 stores in Arkansas and reached $9 million in sales.[31] In 1968, it opened its first stores outside Arkansas in Sikeston, Missouri and Claremore, Oklahoma.[32]

1969–1990: Incorporation and growth as a regional power

The company was incorporated as Wal-Mart, Inc. on October 31, 1969, and changed its name to Wal-Mart Stores, Inc. in 1970. The same year, the company opened a home office and first distribution center in Bentonville, Arkansas. It had 38 stores operating with 1,500 employees and sales of $44.2 million. It began trading stock as a publicly held company on October 1, 1970, and was soon listed on the New York Stock Exchange. The first stock split occurred in May 1971 at a price of $47 per share. By this time, Walmart was operating in five states: Arkansas, Kansas, Louisiana, Missouri, and Oklahoma; it entered Tennessee in 1973 and Kentucky and Mississippi in 1974. As the company moved into Texas in 1975, there were 125 stores with 7,500 employees and total sales of $340.3 million.[32]

In the 1980s, Walmart briefly experimented with a precursor to the Supercenter, the Hyper-Mart. Four stores combined features of discount stores, supermarkets, pharmacies, video arcades and other amenities.[33] Walmart continued to grow rapidly, and by the company's 25th anniversary in 1987, there were 1,198 Walmart stores with sales of $15.9 billion and 200,000 associates.[32] One reason for Walmart's success between 1980 and 2000 is believed to be its contiguous pattern of expansion over time, building new distribution centers in a hub and spoke framework within driving distance of existing Supercenters.[33]

1987 also marked the completion of the company's satellite network, a $24 million investment linking all stores with two-way voice and data transmissions and one-way video communications with the Bentonville office. At the time, the company was the largest private satellite network, allowing the corporate office to track inventory and sales and to instantly communicate to stores.[34] By 1984, Sam Walton had begun to source between 6% and 40% of his company's products from China.[35] In 1988, Walton stepped down as CEO and was replaced by David Glass.[36] Walton remained as chairman of the board. During this year, the first Walmart Supercenter opened in Washington, MO.[37]

With the contribution of its superstores, the company surpassed Toys "R" Us in toy sales in 1998.[38][39]

1990–2005: Retail rise to multinational status

While it was the third-largest retailer in the United States, Walmart was more profitable than rivals Kmart and Sears by the late 1980s. By 1990, it became the largest U.S. retailer by revenue.[40][41]

Prior to the summer of 1990, Walmart had no presence on the West Coast or in the Northeast (except for a single Sam's Club in New Jersey which opened in November 1989), but in July and October that year, it opened its first stores in California and Pennsylvania, respectively. By the mid-1990s, it was the most powerful retailer in the U.S. and expanded into Mexico in 1991 and Canada in 1994.[42] Walmart stores opened throughout the rest of the U.S., with Vermont being the last state to get a store in 1995.[43]

The company also opened stores outside North America, entering South America in 1995 with stores in Argentina and Brazil; and Europe in July 1999, buying Asda in the United Kingdom for US$10 billion.[44]

In 1997, Walmart was added to the Dow Jones Industrial Average.[45]

In 1998, Walmart introduced the Neighborhood Market concept with three stores in Arkansas.[46] By 2005, estimates indicate that the company controlled about 20 percent of the retail grocery and consumables business.[47]

In 2000, H. Lee Scott became Walmart's president and CEO as the company's sales increased to $165 billion.[48] In 2002, it was listed for the first time as America's largest corporation on the Fortune 500 list, with revenues of $219.8 billion and profits of $6.7 billion. It has remained there every year except 2006, 2009, and 2012.[49][50][51][52][53][54][55][56][57][58][59]

In 2005, Walmart reported US$312.4 billion in sales, more than 6,200 facilities around the world—including 3,800 stores in the United States and 2,800 elsewhere, employing more than 1.6 million associates. Its U.S. presence grew so rapidly that only small pockets of the country remained more than 60 miles (97 kilometers) from the nearest store.[60]

As Walmart expanded rapidly into the world's largest corporation, many critics worried about its effect on local communities, particularly small towns with many "mom and pop" stores. There have been several studies on the economic impact of Walmart on small towns and local businesses, jobs, and taxpayers. In one, Kenneth Stone, a professor of economics at Iowa State University, found that some small towns can lose almost half of their retail trade within ten years of a Walmart store opening.[61] However, in another study, he compared the changes to what small-town shops had faced in the past—including the development of the railroads, the advent of the Sears Roebuck catalog, and the arrival of shopping malls—and concluded that shop owners who adapt to changes in the retail market can thrive after Walmart arrives.[61] A later study in collaboration with Mississippi State University showed that there are "both positive and negative impacts on existing stores in the area where the new supercenter locates."[62]

In the aftermath of Hurricane Katrina in September 2005, Walmart used its logistics network to organize a rapid response to the disaster, donating $20 million, 1,500 truckloads of merchandise, food for 100,000 meals, and the promise of a job for every one of its displaced workers.[63] An independent study by Steven Horwitz of St. Lawrence University found that Walmart, The Home Depot, and Lowe's made use of their local knowledge about supply chains, infrastructure, decision makers and other resources to provide emergency supplies and reopen stores well before the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) began its response.[64] While the company was overall lauded for its quick response amidst criticism of FEMA, several critics were quick to point out that there still remained issues with the company's labor relations.[65]

In 2006, Charles Fishman published The Wal-Mart Effect, examining the operation of Walmart's supply chain. His book caught the attention of the press and the public. Fishman's case studies illustrate Walmart’s drive to lower costs and achieve greater efficiency and suggest that it may have significant upstream effects. Since FIshman's book was published, Walmart has more than doubled in size. Further research on Walmart’s role in the food supply chain has tended to be limited and anecdotal.[33][66]

2005–2010: Initiatives

Environmental initiatives

In November 2005, Walmart announced several environmental measures to increase energy efficiency and improve its overall environmental record, which had previously been lacking.[67] The company's primary goals included spending $500 million a year to increase fuel efficiency in Walmart's truck fleet by 25 percent over three years and double it within ten; reduce greenhouse gas emissions by 20 percent in seven years; reduce energy use at stores by 30 percent; and cut solid waste from U.S. stores and Sam's Clubs by 25 percent in three years. CEO Lee Scott said that Walmart's goal was to be a "good steward of the environment" and ultimately use only renewable energy sources and produce zero waste.[68] The company also designed three new experimental stores with wind turbines, photovoltaic solar panels, biofuel-capable boilers, water-cooled refrigerators, and xeriscape gardens.[69] In this time, Walmart also became the biggest seller of organic milk and the biggest buyer of organic cotton in the world, while reducing packaging and energy costs.[67] In 2007, the company worked with outside consultants to discover its total environmental impact and find areas for improvement. Walmart created its own electric company in Texas, Texas Retail Energy, planned to supply its stores with cheap power purchased at wholesale prices. Through this new venture, the company expected to save $15 million annually and also to lay the groundwork and infrastructure to sell electricity to Texas consumers in the future.[70]

Branding and store design changes

In 2006, Walmart announced that it would remodel its U.S. stores to help it appeal to a wider variety of demographics, including more affluent shoppers. As part of the initiative, the company launched a new store in Plano, Texas, that included high-end electronics, jewelry, expensive wines and a sushi bar.[71]

On September 12, 2007, Walmart introduced new advertising with the slogan, "Save money. Live better.", replacing "Always Low Prices, Always", which it had used since 1988. Global Insight, which conducted the research that supported the ads, found that Walmart's price level reduction resulted in savings for consumers of $287 billion in 2006, which equated to $957 per person or $2,500 per household (up 7.3 percent from the 2004 savings estimate of $2,329).[72]

On June 30, 2008, Walmart removed the hyphen from its logo and replaced the star with a Spark symbol that resembles a sunburst, flower, or star. The new logo received mixed reviews from design critics who questioned whether the new logo was as bold as those of competitors, such as the Target bullseye, or as instantly recognizable as the previous company logo, which was used for 18 years.[73] The new logo[74] made its debut on the company's website on July 1, 2008, and its U.S. locations updated store logos in the fall of 2008.[75] Walmart Canada started to adopt the logo for its stores in early 2009.[76]

Acquisitions and employee benefits

On March 20, 2009, Walmart announced that it was paying a combined US$933.6 million in bonuses to every full and part-time hourly worker.[77] This was in addition to $788.8 million in profit sharing, 401(k) pension contributions, hundreds of millions of dollars in merchandise discounts, and contributions to the employees' stock purchase plan.[78] While the economy at large was in an ongoing recession, Walmart reported solid financial figures for the fiscal year ending January 31, 2009, with $401.2 billion in net sales, a gain of 7.2 percent from the prior year. Income from continuing operations increased 3 percent to $13.3 billion, and earnings per share rose 6 percent to $3.35.[79]

On February 22, 2010, the company confirmed it was acquiring video streaming company Vudu, Inc. for an estimated $100 million.[80]

In May 2021, Walmart acquired the Israeli startup Zeekit startup for $200 million. Zeekit uses artificial intelligence to allow customers to try on clothing via a dynamic virtual platform.[81]

2011–2019

Walmart's truck fleet logs millions of miles each year, and the company planned to double the fleet's efficiency between 2005 and 2015.[82] The truck pictured is one of 15 based at Walmart's Buckeye, Arizona, distribution center that was converted to run on biofuel from reclaimed cooking grease made during food preparation at Walmart stores.[83]

Studies of food choice, dietary quality, and health have found that Supercenters in the United States are associated with increases in obesity rates and average body mass, and that shoppers at Walmart do not follow Dietary Guidelines for Americans as well as shoppers at traditional supermarkets.[33] In January 2011, Walmart announced a program to improve the nutritional value of its store brands over five years, reduce prices for whole foods and vegetables, and open stores in low-income areas, so-called "food deserts", where there are no supermarkets.[84] Subsequent research is limited. Walmart may increase food access and decrease food instability, but it does not appear to increase dietary quality.[33]

On April 23, 2011, the company announced that it was testing its new "Walmart To Go" home delivery system where customers will be able to order specific items offered on their website. The initial test was in San Jose, California, and the company has not yet said whether the delivery system will be rolled out nationwide.[85]

On November 14, 2012, Walmart launched its first mail subscription service called Goodies. Customers pay a $7 monthly subscription for five to eight delivered food samples each month, so they can try new foods.[86] The service shut down in late 2013.[87]

In August 2013, the firm announced it was in talks to acquire a majority stake in the Kenya-based supermarket chain, Naivas.[88]

In June 2014, some Walmart employees went on strike in major U.S. cities demanding higher wages.[89] In July 2014, American actor and comedian Tracy Morgan launched a lawsuit against Walmart seeking punitive damages over a multi-car pile-up which the suit alleges was caused by the driver of one of the firm's tractor-trailers who had not slept for 24 hours. Morgan's limousine was apparently hit by the trailer, injuring him and two fellow passengers and killing a fourth, fellow comedian James McNair.[90] Walmart settled with the McNair family for $10 million, while admitting no liability.[91] Morgan and Walmart reached a settlement in 2015 for an undisclosed amount,[92] though Walmart later accused its insurers of "bad faith" in refusing to pay the settlement.[93]

In 2015, the company closed five stores on short notice for plumbing repairs.[94] However, employees and the United Food and Commercial Workers International Union (UFCW) alleged some stores were closed in retaliation for strikes aimed at increasing wages and improving working conditions.[95] The UFCW filed a complaint with the National Labor Relations Board. All five stores have since reopened.[96]

In 2015, Walmart was the biggest US commercial producer of solar power with 142 MW capacity, and had 17 energy storage projects.[97][98] This solar was primarily on rooftops, whereas there is an additional 20,000 m2 for solar canopies over parking lots.[99]

On January 15, 2016, Walmart announced it would close 269 stores in 2016, affecting 16,000 workers.[103] One hundred and fifty-four of these stores earmarked for closure were in the U.S. (150 Walmart U.S. stores, 115 Walmart International stores, and 4 Sam's Clubs). Ninety-five percent of these U.S. stores were located, on average, 10 miles from another Walmart store. The 269 stores represented less than 1 percent of global square footage and revenue for the company. The 102 locations of Neighborhood Markets that were formerly or originally planned to be Walmart Express, which had been in a pilot program since 2011 and converted in to Neighborhood Markets in 2014, were included in the closures. Walmart planned to focus on "strengthening Supercenters, optimizing Neighborhood Markets, growing the e-commerce business and expanding pickup services for customers". In fiscal 2017, the company plans to open between 50 and 60 Supercenters, 85 to 95 Neighborhood Markets, 7 to 10 Sam's Clubs, and 200 to 240 international locations.[104] At the end of fiscal 2017, Walmart opened 38 Supercenters and relocated, expanded or converted 21 discount stores into Supercenters, for a total of 59 Supercenters, and opened 69 Neighborhood Markets, 8 Sam's Clubs, and 173 international locations, and relocated, expanded or converted 4 locations for a total of 177 international locations. On August 8, 2016, Walmart announced a deal to acquire e-commerce website Jet.com for US$3.3 billion.[105][106] Jet.com co-founder and CEO Marc Lore stayed on to run Jet.com in addition to Walmart's existing U.S. e-commerce operation. The acquisition was structured as a payout of $3 billion in cash, and an additional $300 million in Walmart stock vested over time as part of an incentive bonus plan for Jet.com executives.[107] On October 19, 2016, Walmart announced it would partner with IBM and Tsinghua University to track the pork supply chain in China using blockchain.[108]

On February 15, 2017, Walmart announced the acquisition of Moosejaw, a leading online active outdoor retailer, for approximately $51 million. The acquisition closed on February 13, 2017.[109] On June 16, 2017, Walmart agreed to acquire the men's apparel company Bonobos for $310 million in an effort to expand its fashion holdings.[110] On September 29, 2017, Walmart acquired Parcel, a technology-based, same-day and last-mile delivery company in Brooklyn.[111] In 2018, Walmart started crowdsourcing delivery services to customers using drivers' private vehicles, under the brand "Spark".[112]

On December 6, 2017, Walmart announced that it would change its corporate name to Walmart Inc. from Wal-Mart Stores, Inc. effective February 1, 2018.[113][114]

On January 11, 2018, Walmart announced that 63 Sam's Club locations in cities including Memphis, Houston, Seattle, and others would be closing. Some of the stores had already liquidated, without notifying employees; some employees learned by a company-wide email delivered January 11. All of the 63 stores were gone from the Sam's Club website as of the morning of January 11. Walmart said that ten of the stores will become e-commerce distribution centers and employees can reapply to work at those locations. Business Insider magazine calculated that over 11,000 workers will be affected.[115][116] On the same day, Walmart announced that as a result of the new tax law, it would be raising Walmart starting wages, distributing bonuses, expanding its leave policies and contributing toward the cost of employees' adoptions. Doug McMillon, Walmart's CEO, said, "We are early in the stages of assessing the opportunities tax reform creates for us to invest in our customers and associates and to further strengthen our business, all of which should benefit our shareholders."[117]

In March 2018, Walmart announced that it is producing its own brand of meal kits in all of its stores that is priced under Blue Apron designed to serve two people.[118]

It was reported that Walmart is now looking at entering the subscription-video space, hoping to compete with Netflix and Amazon. They have enlisted the help of former Epix CEO, Mark Greenberg, to help develop a low-cost subscription video-streaming service.[119]

In September 2018, Walmart partnered with comedian and talk show host Ellen DeGeneres to launch a new brand of women's apparel and accessories called EV1.[120]

On February 26, 2019, Walmart announced that it had acquired Tel Aviv-based product review start-up Aspectiva for an undisclosed sum.[121]

In May 2019, Walmart announced the launch of free one-day shipping on more than 220,000 items with minimum purchase amount of $35.[122] The initiative first launched in Las Vegas and the Phoenix area.[123]

In September 2019, Walmart made the announcement that it would cease the sale of all e-cigarettes due to "regulatory complexity and uncertainty" over the products. Earlier in 2019, Walmart stopped selling fruit-flavored e-cigarette and had raised the minimum age to 21 for the purchase of products containing tobacco.[124] That same month, Walmart opened its first Health Center, a "medical mall" where customers can purchase primary care services, such as vision tests, dental exams and root canals, lab work, X-rays and EKGs, counseling, and fitness and diet classes. Prices without insurance were listed, for instance, at $30 for an annual physical and $45 for a counseling session.[125] Continuing with its health care initiative, they opened a 2,600 square feet (240 m2) health and wellness clinic prototype in Springdale, Arkansas just to expand services.[126]

As of October 2019, Walmart stopped selling all live fish and aquatic plants.[127]

2020s: Continuing growth and development

This decade, as with many other companies, started off very unorthodox and unusual, due to the large part of the coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic, including store closures, limited store occupancy, and employment, along with social distancing protocols. The store hours were adjusted to allow cleaning and stocking.

In March 2020, due to the pandemic, Walmart changed some of its employee benefits. Employees can now decide to stay home and take unpaid leave if they feel unable to work or uncomfortable coming to work. Additionally, Walmart employees who contract the virus will receive "up to two weeks of pay". After two weeks, hourly associates who are unable to return to work are eligible for up to 26 weeks in pay.[128] As of July 21, 2020, Walmart paid pandemic bonuses of $428 million to staff. People who did part-time or temporary work received a bonus of $150 while those who worked full-time received a bonus of $300.[129] In July 2020, Walmart announced that all customers would be required to wear masks in all stores nationwide, including Sam's Club.[130]

In the first quarter of 2020, consumers responded to COVID by shopping less frequently (5.6% fewer transactions), and buying more when they did shop (16.5%).[131] As people shifted from eating out to eating at home,[33] net sales at Walmart increased by 10.5%, while online sales rose by 74%. Although Walmart experienced a 5.5% increase in operating expenses, its net income increased by 3.9%.[131] In the third quarter of 2020, ending October 31, Walmart reported revenue of $134.7 billion, representing a year-on-year increase of 5.2 percent.[132]

In December 2020, Walmart launched a new service, Carrier Pickup, that allows the customers to schedule a return for a product bought online, in-store, or from a third-party vendor. These services can be initiated on the Walmart App or on the website.[133]

In January 2021, Walmart announced that the company is launching a fintech startup, with venture partner Ribbit Capital, to provide financial products for consumers and employees.[134]

In February 2021, Walmart acquired technology from Thunder Industries, which uses automation to create digital ads, to expand its online marketing capabilities.[135]

In August 2021, Walmart announced it would open its Spark crowdsource delivery to other businesses as a white-label service, competing with Postmates and online food ordering delivery companies.[112]

In December 2021, Walmart announced it will participate in the Stephens Investment Conference Wednesday, and the Morgan Stanley Virtual Global Consumer & Retail Conference.[136] In June of 2022, Walmart announced it would be acquiring Memomi, an AR optical tech company. [137]

In August 2022, Walmart announced it would be acquiring Volt Systems, a vendor management and product tracking software company. [138] Walmart announced it was partnering with Paramount to offer Paramount+ content to it's Walmart+ subscribers in a bid to better compete with Amazon. [139]

Walmart announced in August 2022 that locations were not going back to 24 hours.[140]

Operating divisions

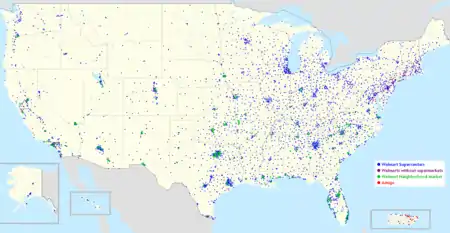

Legend:

As of 2016, Walmart's operations are organized into four divisions: Walmart U.S., Walmart International, Sam's Club and Global eCommerce.[141] In the United States, Walmart's stores operate in four formats: discount, Supercenters. Neighborhood Markets, and Sam’s Club stores.[33] Walmart International stores include additional formats such as supermarkets, hypermarkets, cash-and-carry stores, home improvement, specialty electronics, restaurants, apparel stores, drugstores, and convenience stores.[142]

Walmart U.S.

Walmart U.S. is the company's largest division, accounting for US$331.666 billion, or 65 percent of total sales, for fiscal 2019.[15][16] It consists of three retail formats that have become commonplace in the United States: Supercenters, Discount Stores, Neighborhood Markets, and other small formats. The discount stores sell a variety of mostly non-grocery products, though emphasis has now shifted towards supercenters, which include more groceries. As of July 31, 2022, there are a total of 4,735 Walmart U.S. stores.[2][3] In the United States, 90 percent of the population resides within 10 miles of a Walmart store.[143] The total number of Walmart U.S. stores and Sam's Clubs combined is 5,335.[2][3]

The president and CEO of Walmart U.S. is John Furner.[144][145]

Walmart Supercenter

Walmart Supercenters, branded simply as "Walmart", are hypermarkets with sizes varying from 69,000 to 260,000 square feet (6,400 to 24,200 square meters), but averaging about 178,000 square feet (16,500 square meters).[4] These stock general merchandise and a full-service supermarket, including meat and poultry, baked goods, delicatessen, frozen foods, dairy products, garden produce, and fresh seafood. Many Walmart Supercenters also have a garden center, pet shop, pharmacy, Tire & Lube Express, optical center, one-hour photo processing lab, portrait studio, and numerous alcove shops, such as cellular phone stores, hair and nail salons, video rental stores, local bank branches (such as Woodforest National Bank branches in newer locations), and fast food outlets.

Many Walmart Supercenters currently feature McDonald's or Subway restaurants. In some Canadian locations, Tim Hortons were opened. Recently, in several Supercenters, like the Tallahassee, Florida and the Palm Desert, California locations, Walmart added Burger King to their locations, and the location in Glen Burnie, Maryland, due to its past as a hypermarket called Leedmark, which operated from May 1991 to January 1994, boasts an Auntie Anne's and an Italian restaurant.

Some locations also have fuel stations which sell gasoline distributed by Murphy USA (which spun off from Murphy Oil in 2013), Sunoco, Inc. ("Optima"), the Tesoro Corporation ("Mirastar"), USA Gasoline, and even now Walmart-branded gas stations.[146]

The first Supercenter opened in Washington, Missouri, in 1988. A similar concept, Hypermart USA, had opened a year earlier in Garland, Texas. All Hypermart USA stores were later closed or converted into Supercenters.

As of July 31, 2022, there were 3,572 Walmart Supercenters in 49 of the 50 U.S. states, the District of Columbia, and Puerto Rico.[2][3] Hawaii is the only state to not have a Supercenter location. The largest Supercenter in the world, covering 260,000 square feet (24,000 square meters) on two floors, is located in Crossgates Commons in Albany, New York.[147]

A typical supercenter sells approximately 120,000 items, compared to the 35 million products sold in Walmart's online store.[148]

The "Supercenter" name has since been phased out, with these stores now simply referred to as "Walmart", since the company introduced the new Walmart logo in 2008. However, the branding is still used in Walmart's Canadian stores (spelled as "Supercentre" in Canadian English).[149]

Walmart Discount Store

.jpg.webp)

Walmart Discount Stores, also branded as simply "Walmart", are discount department stores with sizes varying from 30,000 to 221,000 square feet (2,800 to 20,500 square meters), with the average store covering 105,000 square feet (9,800 square meters).[4] They carry general merchandise and limited groceries. Some newer and remodeled discount stores have an expanded grocery department, similar to Target's PFresh department. Many of these stores also feature a garden center, pharmacy, Tire & Lube Express, optical center, one-hour photo processing lab, portrait studio, a bank branch, a cell phone store, and a fast food outlet. Some also have gasoline stations.[146] Discount Stores were Walmart's original concept, though they have since been surpassed by Supercenters.[33]

In 1990, Walmart opened its first Bud's Discount City location in Bentonville. Bud's operated as a closeout store, much like Big Lots. Many locations were opened to fulfill leases in shopping centers as Walmart stores left and moved into newly built Supercenters. All of the Bud's Discount City stores had closed or converted into Walmart Discount Stores by 1997.[150]

At its peak in 1996, there were 1,995 Walmart Discount Stores,[151] but as of July 31, 2022, that number was dropped to 367.[2][3]

Walmart Neighborhood Market

Walmart Neighborhood Market, sometimes branded as "Neighborhood Market by Walmart" or informally known as "Neighborhood Walmart", is Walmart's chain of supermarkets ranging from 28,000 to 65,000 square feet (2,600 to 6,000 square meters) and averaging about 42,000 square feet (3,900 square meters), about a fifth of the size of a Walmart Supercenter.[4][152] The first Walmart Neighborhood Market opened ten years after the first Supercenter opened, yet Walmart renewed its focus on the smaller grocery store format in the 2010s.[153]

The stores focus on three of Walmart's major sales categories: groceries, which account for about 55 percent of the company's revenue,[154][155] pharmacy, and, at some stores, fuel.[156] For groceries and consumables, the stores sell fresh produce, deli and bakery items, prepared foods, meat, dairy, organic, general grocery and frozen foods, in addition to cleaning products and pet supplies.[152][157] Some stores offer wine and beer sales[152] and drive-through pharmacies. Some stores, such as one at Midtown Center in Bentonville, Arkansas, offer made-to-order pizza with a seating area for eating.[158] Customers can also use Walmart's site-to-store operation and pick up online orders at Walmart Neighborhood Market stores just like the Supercenters and Discount Stores[159]

Products at Walmart Neighborhood Market stores carry the same prices as those at Walmart's larger supercenters. A Moody's analyst said the wider company's pricing structure gives the chain of grocery stores a "competitive advantage" over competitors Whole Foods, Kroger and Trader Joe's.[156]

Neighborhood Market stores expanded slowly at first as a way to fill gaps between Walmart Supercenters and Discount Stores in existing markets. In its first 12 years, the company opened about 180 Walmart Neighborhood Markets. By 2010, Walmart said it was ready to accelerate its expansion plans for the grocery stores.[160] As of July 31, 2022, there were 682 Walmart Neighborhood Markets,[2][3] each employing between 90 and 95 full-time and part-time workers.[161]

Neighborhood Market, depending on the area, has some competition with Hy-Vee Fast & Fresh, which launched in 2019 that is similar to Neighborhood Market.

Former stores and concepts

Walmart opened Supermercado de Walmart locations to appeal to Hispanic communities in the United States.[162] The first one, a 39,000-square-foot (3,600-square-meter) store in the Spring Branch area of Houston, opened on April 29, 2009.[163] The store was a conversion of an existing Walmart Neighborhood Market.[164] In 2009, another Supermercado de Walmart opened in Phoenix, Arizona.[165] Both locations closed in 2014.[166] In 2009, Walmart opened "Mas Club", a warehouse retail operation patterned after Sam's Club. Its lone store also closed in 2014.[163]

Walmart Express was a chain of smaller discount stores with a range of services from groceries to check cashing and gasoline service. The concept was focused on small towns deemed unable to support a larger store and large cities where space was at a premium. Walmart planned to build 15 to 20 Walmart Express stores, focusing on Arkansas, North Carolina, and Chicago, by the end of its fiscal year in January 2012. As of September 2014, Walmart re-branded all 22[167] of its Express format stores to Neighborhood Markets in an effort to streamline its retail offer. It continued to open new Express stores under the Neighborhood Market name. As of July 31, 2022, there were 102 small-format stores in the United States. These include 93 other small formats, 8 convenience stores and 1 pickup location.[2][3] On January 15, 2016, Walmart announced that it would be closing 269 stores globally, including the 102 Neighborhood Markets that were formerly or originally planned to be Express stores.[168]

Between 2002 and 2022, Walmart owned 12 Amigo supermarkets in Puerto Rico. In 2022, Walmart announced that it would sell its Amigo stores to Pueblo Inc. and focus on modernizing its 18 Supercenter and Division 1 formats and 7 Sam’s Clubs stores.[169]

Initiatives

In September 2006, Walmart announced a pilot program to sell generic drugs at $4 per prescription. The program was launched at stores in the Tampa, Florida, area, and by January 2007 had been expanded to all stores in Florida. While the average price of generics is $29 per prescription, compared to $102 for name-brand drugs, Walmart maintains that it is not selling at a loss, or providing them as an act of charity—instead, they are using the same mechanisms of mass distribution that it uses to bring lower prices to other products.[170] Many of Walmart's low cost generics are imported from India, where they are made by drug makers that include Ranbaxy and Cipla.[171]

On February 6, 2007, the company launched a "beta" version of a movie download service, which sold about 3,000 films and television episodes from all major studios and television networks.[172] The service was discontinued on December 21, 2007, due to low sales.[173]

In 2008, Walmart started a pilot program in the small grocery store concept called Marketside in the metropolitan Phoenix, Arizona, area. The four stores closed in 2011.[174]

In 2015, Walmart began testing a free grocery pickup service, allowing customers to select products online and choose their pickup time. At the store, a Walmart employee loads the groceries into the customer's car. As of December 17, 2017, the service is available in 39 U.S. states.[175]

In May 2016, Walmart announced a change to ShippingPass, its three-day shipping service, and that it will move from a three-day delivery to two-day delivery to remain competitive with Amazon.[176] Walmart priced it at 49 dollars per year, compared to Amazon Prime's 99-dollar-per-year price.[177][178]

In June 2016, Walmart and Sam's Club announced that they would begin testing a last-mile grocery delivery that used services including Uber, Lyft, and Deliv, to bring customers' orders to their homes. Walmart customers would be able to shop using the company's online grocery service at grocery.walmart.com, then request delivery at checkout for a small fee. The first tests were planned to go live in Denver and Phoenix.[179] Walmart announced on March 14, 2018, that it would expand online delivery to 100 metropolitan regions in the United States, the equivalent of 40 percent of households, by the end of the year of 2018.[180]

Walmart's Winemakers Selection private label wine was introduced in June 2018 in about 1,100 stores. The wine, from domestic and international sources, was described by Washington Post food and wine columnist Dave McIntyre as notably good for the inexpensive ($11 to $16 per bottle) price level.[181]

In October 2019, Walmart announced that customers in 2,000 locations in 29 states can use the grocery pickup service for their adult beverage purchases. Walmart will also deliver adult beverages from nearly 200 stores across California and Florida.[182]

In February 2020, Walmart announced a new membership program called, "Walmart +". The news came shortly after Walmart announced the discontinuation of its personal shopping service, Jetblack.[183][184]

Numbers of stores by state

Locations as of August 13, 2022

| State | Supercenters | Discount Stores | Neighborhood Markets | Amigos | Sam's Clubs | Other Pharmacy Formats | Total stores |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alabama[185] | 101 | 1 | 28 | 13 | 1 | 144 | |

| Alaska[186] | 7 | 2 | 9 | ||||

| Arizona[187] | 84 | 2 | 26 | 12 | 124 | ||

| Arkansas[188] | 76 | 5 | 33 | 11 | 8 | 133 | |

| California[189] | 144 | 68 | 66 | 30 | 1 | 309 | |

| Colorado[190] | 70 | 4 | 14 | 17 | 105 | ||

| Connecticut[191] | 12 | 21 | 1 | 34 | |||

| Delaware[192] | 6 | 3 | 1 | 10 | |||

| District of Columbia[193] | 3 | 3 | |||||

| Florida[194] | 232 | 9 | 98 | 46 | 2 | 387 | |

| Georgia[195] | 154 | 2 | 31 | 24 | 3 | 214 | |

| Hawaii[196] | 10 | 2 | 12 | ||||

| Idaho[197] | 23 | 3 | 1 | 27 | |||

| Illinois[198] | 139 | 15 | 5 | 25 | 184 | ||

| Indiana[199] | 97 | 6 | 9 | 13 | 2 | 127 | |

| Iowa[200] | 58 | 2 | 9 | 69 | |||

| Kansas[201] | 58 | 2 | 14 | 9 | 83 | ||

| Kentucky[202] | 77 | 7 | 7 | 9 | 1 | 101 | |

| Louisiana[203] | 88 | 2 | 33 | 14 | 1 | 138 | |

| Maine[204] | 19 | 3 | 3 | 25 | |||

| Maryland[205] | 31 | 16 | 11 | 2 | 60 | ||

| Massachusetts[206] | 27 | 21 | 48 | ||||

| Michigan[207] | 90 | 3 | 23 | 1 | 117 | ||

| Minnesota[208] | 65 | 3 | 12 | 80 | |||

| Mississippi[209] | 65 | 3 | 10 | 7 | 1 | 86 | |

| Missouri[210] | 112 | 9 | 16 | 19 | 156 | ||

| Montana[211] | 14 | 2 | 16 | ||||

| Nebraska[212] | 35 | 7 | 5 | 47 | |||

| Nevada[213] | 30 | 2 | 11 | 7 | 50 | ||

| New Hampshire[214] | 19 | 7 | 2 | 28 | |||

| New Jersey[215] | 35 | 27 | 8 | 70 | |||

| New Mexico[216] | 35 | 2 | 9 | 7 | 53 | ||

| New York[217] | 82 | 16 | 1 | 12 | 111 | ||

| North Carolina[218] | 143 | 6 | 43 | 22 | 214 | ||

| North Dakota[219] | 14 | 3 | 17 | ||||

| Ohio[220] | 138 | 6 | 27 | 171 | |||

| Oklahoma[221] | 81 | 7 | 33 | 13 | 134 | ||

| Oregon[222] | 29 | 7 | 9 | 45 | |||

| Pennsylvania[223] | 116 | 20 | 24 | 160 | |||

| Puerto Rico[224] | 13 | 5 | 12 | 7 | 37 | ||

| Rhode Island[225] | 5 | 4 | 9 | ||||

| South Carolina[226] | 83 | 26 | 13 | 122 | |||

| South Dakota[227] | 15 | 2 | 17 | ||||

| Tennessee[228] | 117 | 1 | 18 | 14 | 150 | ||

| Texas[229] | 391 | 18 | 97 | 82 | 5 | 593 | |

| Utah[230] | 41 | 10 | 8 | 59 | |||

| Vermont[231] | 3 | 3 | 6 | ||||

| Virginia[232] | 110 | 4 | 20 | 15 | 149 | ||

| Washington[233] | 52 | 9 | 4 | 65 | |||

| West Virginia[234] | 38 | 5 | 1 | 44 | |||

| Wisconsin[235] | 83 | 4 | 2 | 10 | 99 | ||

| Wyoming[236] | 12 | 2 | 14 |

Walmart International

As of July 31, 2022, Walmart's international operations comprised 5,250 stores[2][3] and 800,000 workers in 23 countries outside the United States.[237] There are wholly owned operations in Argentina, Brazil, Canada, and the UK. With 2.2 million employees worldwide, the company is the largest private employer in the U.S. and Mexico, and one of the largest in Canada.[8] In fiscal 2019 Walmart's international division sales were US$120.824 billion, or 23.7 percent of total sales.[15][16] International retail units range from 1,400 to 186,000 square feet (130 to 17,280 square meters), while wholesale units range from 24,000 to 158,000 square feet (2,200 to 14,700 square meters).[4] Judith McKenna is the president and CEO of Walmart International .[238][145]

Central America

Walmart also owns 51 percent of the Central American Retail Holding Company (CARHCO), which, as of July 31, 2022, consists of 867 stores, including 263 stores in Guatemala (under the Paiz [27 locations], Walmart Supercenter [10 locations], Despensa Familiar [181 locations], and Maxi Dispensa [45 locations] banners),[2][3] 102 stores in El Salvador (under the Despensa Familiar [63 locations], La Despensa de Don Juan [17 locations], Walmart Supercenter [6 locations], and Maxi Despensa [16 locations] banners),[2][3] 111 stores in Honduras (including the Paiz [8 locations], Walmart Supercenter [4 locations], Dispensa Familiar [71 locations], and Maxi Despensa [28 locations] banners),[2][3] 102 stores in Nicaragua (including the Pali [71 locations], La Unión [9 locations], Maxi Pali [20 locations], and Walmart Supercenter [2 locations] banners),[2][3] and 289 stores in Costa Rica (including the Maxi Pali [49 locations], Mas X Menos [38 locations], Walmart Supercenter [14 locations], and Pali [188 locations] banners[2][3]).[239]

Chile

In January 2009, the company acquired a controlling interest in the largest grocer in Chile, Distribución y Servicio D&S SA.[240][241] In 2010, the company was renamed Walmart Chile.[242] As of July 31, 2022, Walmart Chile operates 385 stores under the banners Lider Hiper (96 locations), Lider Express (155 locations), Superbodega Acuenta (122 locations), and Central Mayorista (12 locations).[2][3]

Mexico

Walmart opened its first international store in Mexico in 1991.[33] As of July 31, 2022, Walmart's Mexico division, the largest outside the U.S., consisted of 2,784 stores.[2][3] Walmart in Mexico operates Walmart Supercenter (299 locations), Sam's Club (166 locations), Bodega Aurrera (567 locations), Mi Bodega Aurrera (433 locations), Bodega Aurrera Express (1,220 locations) and Walmart Express (99 locations).[3]

Canada

Walmart has operated in Canada since it acquired 122 stores comprising the Woolco division of Woolworth Canada, Inc on January 14, 1994.[243] As of July 31, 2022, it operates 402 locations (including 343 supercentres and 59 discount stores)[2][3] and, as of June 2015, it employs 89,358 people, with a local home office in Mississauga, Ontario.[244] Walmart Canada's first three Supercentres (spelled in Canadian English) opened in November 2006 in Ancaster, London, and Stouffville, Ontario.[245] The 100th Canadian Supercentre opened in July 2010, in Victoria, British Columbia.

In 2010, approximately one year after its incorporation of Schedule 2 (foreign-owned, deposit-taking) of Canada's Bank Act,[246] Walmart Canada Bank was introduced with the launch of the Walmart (Canada) Rewards MasterCard.[247] Less than ten years later, however, on May 17, 2018, Wal-Mart Canada announced it had reached a definitive agreement to sell Wal-Mart Canada Bank to First National co-founder Stephen Smith and private equity firm Centerbridge Partners, L.P., on undisclosed financial terms, though it added that it would still be issuer of the Walmart (Canada) Rewards MasterCard.[248]

On April 1, 2019, Centerbridge Partners, L.P. and Stephen Smith jointly announced the closing of the previously announced acquisition of Wal-Mart Canada Bank and that it was to be renamed Duo Bank of Canada, to be styled simply as Duo Bank.[249][250] Though exact ownership percentages were never revealed in either company announcement, it has also since been revealed that Duo Bank was reclassified as a Schedule 1 (domestic, deposit-taking)[251][252] federally chartered bank of the Bank Act in Canada from the Schedule 2 (foreign-owned or -controlled, deposit-taking)[252] that it had been, which indicates that Stephen Smith, as a noted Canadian businessman, is in a controlling position.

Africa

On September 28, 2010, Walmart announced it would buy Massmart Holdings Ltd. of Johannesburg, South Africa in a deal worth over US$4 billion giving the company its first footprint in Africa.[253] As of July 31, 2022, it has 412 stores, including 362 stores in South Africa (under the banners Game Foodco [78 locations], CBW [41 locations], Game [39 locations], Builders Express [50 locations], Builders Warehouse [34 locations], Cambridge [42 locations], Rhino [15 locations], Makro [23 locations], Builders Trade Depot [9 locations], Jumbo [13 locations], and Builders Superstore [18 locations]),[2][3] 11 stores in Botswana (under the banners CBW [7 locations], Game Foodco [2 locations], and Builders Warehouse [2 locations]),[2][3] 4 stores in Ghana (under the Game Foodco banner),[2][3] 4 stores in Kenya (under the banners Game Foodco [3 locations] and Builders Warehouse [1 location]),[2][3] 3 stores in Lesotho (under the banners CBW [2 locations] and Game Foodco [1 location]),[2] 2 stores in Malawi (under the Game banner),[2][3] 6 stores in Mozambique (under the banners Builders Warehouse [2 locations], Game Foodco [2 locations], CBW [1 location], and Builders Express [1 location]),[2][3] 5 stores in Namibia (under the banners Game Foodco [4 locations] and Game [1 location]),[2][3] 5 stores in Nigeria (under the banners Game [3 locations] and Game Foodco [2 location]),[2][3] 1 store in Swaziland (under the CBW banner),[2][3] 1 store in Tanzania (under the Game Foodco banner),[2][3] 1 store in Uganda (under the Game banner),[2][3] and 7 stores in Zambia (under the banners CBW [1 location], Game Foodco [3 locations], Builders Warehouse [2 locations], and Builders Express [1 location]).[2][3]

China

Walmart has joint ventures in China and several majority-owned subsidiaries. As of July 31, 2022, Walmart China (沃尔玛 Wò'ērmǎ)[254] operates 372 stores under the Walmart Supercenter (336 locations) and Sam's Club (36 locations) banners.[2][3]

In February 2012, Walmart announced that the company raised its stake to 51 percent in Chinese online supermarket Yihaodian to tap rising consumer wealth and help the company offer more products. Walmart took full ownership in July 2015.[255]

In December 2021, the Chinese Communist Party's Central Commission for Discipline Inspection warned Walmart about not stocking products made from inputs from Xinjiang in response to the Uyghur Forced Labor Prevention Act.[256]

India

In November 2006, the company announced a joint venture with Bharti Enterprises to operate in India. As foreign corporations were not allowed to enter the retail sector directly, Walmart operated through franchises and handled the wholesale end of the business.[257] The partnership involved two joint ventures—Bharti manages the front end, involving opening of retail outlets while Walmart takes care of the back end, such as cold chains and logistics. Walmart operates stores in India under the name Best Price Modern Wholesale.[258] The first store opened in Amritsar on May 30, 2009. On September 14, 2012, the Government of India approved 51 percent FDI in multi-brand retails, subject to approval by individual states, effective September 20, 2012.[259][260] Scott Price, Walmart's president and CEO for Asia, told The Wall Street Journal that the company would be able to start opening Walmart stores in India within two years.[261] Expansion into India faced some significant problems. In November 2012, Walmart admitted to spending US$25 million lobbying the Indian National Congress;[262] lobbying is conventionally considered bribery in India.[263] Walmart is conducting an internal investigation into potential violations of the Foreign Corrupt Practices Act.[264] Bharti Walmart suspended a number of employees, rumored to include its CFO and legal team, to ensure "a complete and thorough investigation".[265] In October 2013, Bharti and Walmart separated to pursue business independently.[266]

On May 9, 2018, Walmart announced its intent to acquire a 77% majority stake in the Indian e-commerce company Flipkart for $16 billion, in a deal that was completed on August 18, 2018.[267][268][269] As of July 31, 2022, there are 28 Best Price Modern Wholesale locations.[2][3]

Setbacks

In the 1990s, Walmart tried with a large financial investment to get a foothold in both German and Indonesian retail markets.

Walmart entered Indonesia with the opening of stores in Lippo Supermall (now known as Supermal Karawaci) and Megamall Pluit (now known as Pluit Village) respectively, under a joint-venture agreement with local conglomerate Lippo Group. Both stores closed down due to the 1997 Asian financial crisis.[270][271][272]

In 1997, Walmart took over the supermarket chain Wertkauf with its 21 stores for DM 750 million[273] and the following year Walmart acquired 74 Interspar stores for DM 1.3 billion.[274][275] The German market at this point was an oligopoly with high competition among companies which used a similar low price strategy as Walmart. As a result, Walmart's low price strategy yielded no competitive advantage. Walmart's corporate culture was not viewed positively among employees and customers, particularly Walmart's "statement of ethics", which attempted to restrict relationships between employees, a possible violation of German labor law, and led to a public discussion in the media, resulting in a bad reputation among customers.[276][277] In July 2006, Walmart announced its withdrawal from Germany due to sustained losses. The stores were sold to the German company Metro during Walmart's fiscal third quarter.[278][279] Walmart did not disclose its losses from its German investment, but they were estimated to be around €3 billion.[280]

In 2004, Walmart bought the 118 stores in the Bompreço supermarket chain in northeastern Brazil. In late 2005, it took control of the Brazilian operations of Sonae Distribution Group through its new subsidiary, WMS Supermercados do Brasil, thus acquiring control of the Nacional and Mercadorama supermarket chains, the leaders in the Rio Grande do Sul and Paraná states, respectively. None of these stores were rebranded. As of January 2014, Walmart operated 61 Bompreço supermarkets, 39 Hiper Bompreço stores. It also ran 57 Walmart Supercenters, 27 Sam's Clubs, and 174 Todo Dia stores. With the acquisition of Bompreço and Sonae, by 2010, Walmart was the third-largest supermarket chain in Brazil, behind Carrefour and Pão de Açúcar.[281]

Walmart Brasil, the operating company, has its head office in Barueri, São Paulo State, and regional offices in Curitiba, Paraná; Porto Alegre, Rio Grande do Sul; Recife, Pernambuco; and Salvador, Bahia.[282] Walmart Brasil operates under the banners Todo Dia, Nacional, Bompreço, Walmart Supercenter, Maxxi Atacado, Hipermercado Big, Hiper Bompreço, Sam's Club, Mercadorama, Walmart Posto (Gas Station), Supermercado Todo Dia, and Hiper Todo Dia. Recently, the company started the conversion process of all Hiper Bompreço and Big stores into Walmart Supercenters and Bompreço, Nacional and Mercadorama stores into the Walmart Supermercado brand.

Since August 2018, Walmart Inc. only holds a minority stake in Walmart Brasil, which was renamed Grupo Big on August 12, 2019,[283] with 20% of the company's shares, and private equity firm Advent International holding 80% ownership of the company.[284] On March 24, 2021, it was announced that Carrefour would be acquiring Grupo Big.[285]

Walmart Argentina was founded in 1995 and operates stores under the banners Walmart Supercenter, Changomas, Mi Changomas, and Punto Mayorista. On November 6, 2020, it was announced that Walmart has sold its Argentine operations to Grupo de Narváez.[286]

Walmart's UK subsidiary Asda (which retained its name after being acquired by Walmart) is based in Leeds and accounted for 42.7 percent of 2006 sales of Walmart's international division. In contrast to the U.S. operations, Asda was originally and still remains primarily a grocery chain, but with a stronger focus on non-food items than most UK supermarket chains other than Tesco. In 2010 Asda acquired stores from Netto UK. In addition to small suburban Asda Supermarkets,[3] larger stores are branded Supercentres.[3] Other banners include Asda Superstores, Asda Living, and Asda Petrol Fueling Station.[2][3][287] In July 2015, Asda updated its logo featuring the Walmart Asterisks behind the first 'A' in the Logo. In May 2018, Walmart announced plans to sell Asda to rival Sainsbury's for $10.1 billion. Under the terms of the deal, Walmart would have received a 42% stake in the combined company and about £3 billion in cash.[288] However, in April 2019, the United Kingdom's Competition and Markets Authority blocked the proposed sale of Asda to Sainsburys.[289]

On October 2, 2020, it was announced that Walmart will sell a majority stake of Asda to a consortium of Zuber and Mohsin Issa (the owners of EG Group) and private equity firm TDR Capital for £6.8bn, pending approval from the Competition and Markets Authority.[290]

In Japan, Walmart owned 100 percent of Seiyu (西友 Seiyū) as of 2008.[278][291] It operates under the Seiyu (Hypermarket), Seiyu (Supermarket), Seiyu (General Merchandise), Livin, and Sunny banners.[2][3] On November 16, 2020, Walmart announced they would be selling 65% of their shares in the company to the private-equity firm KKR in a deal valuing 329 stores and 34,600 employees at $1.6 billion. Walmart is supposed to retain 15% and a seat on the board, while a joint-venture between KKR and Japanese company Rakuten Inc. will receive 20%.[292]

Corruption charges

An April 2012 investigation by The New York Times reported the allegations of a former executive of Walmart de Mexico that, in September 2005, the company had paid bribes via local fixers to officials throughout Mexico in exchange for construction permits, information, and other favors, which gave Walmart a substantial advantage over competitors.[293] Walmart investigators found credible evidence that Mexican and American laws had been broken. Concerns were also raised that Walmart executives in the United States had "hushed up" the allegations. A follow-up investigation by The New York Times, published December 17, 2012, revealed evidence that regulatory permission for siting, construction, and operation of nineteen stores had been obtained through bribery. There was evidence that a bribe of US$52,000 was paid to change a zoning map, which enabled the opening of a Walmart store a mile from a historical site in San Juan Teotihuacán in 2004.[294] After the initial article was released, Walmart released a statement denying the allegations and describing its anti-corruption policy. While an official Walmart report states that it had found no evidence of corruption, the article alleges that previous internal reports had indeed turned up such evidence before the story became public.[295] Forbes magazine contributor Adam Hartung also commented that the bribery scandal was a reflection of Walmart's "serious management and strategy troubles", stating, "[s]candals are now commonplace ... [e]ach scandal points out that Walmart's strategy is harder to navigate and is running into big problems".[296]

In 2012, there was an incident with CJ's Seafood, a crawfish processing firm in Louisiana that was partnered with Walmart, that eventually gained media attention for the mistreatment of its 40 H-2B visa workers from Mexico. These workers experienced harsh living conditions in tightly packed trailers outside of the work facility, physical threats, verbal abuse, and were forced to work day-long shifts. Many of the workers were afraid to take action about the abuse due to the fact that the manager threatened the lives of their family members in the U.S. and Mexico if the abuse were to be reported. Eight of the workers confronted management at CJ's Seafood about the mistreatment; however, the management denied the abuse allegations and the workers went on strike. The workers then took their stories to Walmart due to their partnership with CJ's. While Walmart was investigating the situation, the workers collected 150,000 signatures of supporters who agreed that Walmart should stand by the workers and take action. In June 2012, the visa workers held a protest and day-long hunger strike outside of the apartment building where a Walmart board member resided. Following this protest, Walmart announced its final decision to no longer work with CJ's Seafood. Less than a month later, the Department of Labor fined CJ's Seafood "approximately $460,000 in back-pay, safety violations, wage and hour violations, civil damages, and fines for abuses to the H-2B program. The company has since shut down."[297]

As of December 2012, internal investigations were ongoing into possible violations of the Foreign Corrupt Practices Act.[298] Walmart has invested US$99 million on internal investigations, which expanded beyond Mexico to implicate operations in China, Brazil, and India.[299][300] The case has added fuel to the debate as to whether foreign investment will result in increased prosperity, or if it merely allows local retail trade and economic policy to be taken over by "foreign financial and corporate interests".[301][302]

Sam's Club

Sam's Club is a chain of warehouse clubs that sell groceries and general merchandise, often in bulk.[33] Locations generally range in size from 32,000–168,000 sq ft (3,000–15,600 m2), with an average club size of approximately 134,000 sq ft (12,400 m2).[4] The first Sam's Club was opened by Walmart, Inc. in 1983 in Midwest City, Oklahoma[303] under the name "Sam's Wholesale Club". The chain was named after its founder Sam Walton. As of July 31, 2022, Sam's Club operated 600 membership warehouse clubs and accounted for 11.3% of Walmart's revenue at $57.839 billion in fiscal year 2019.[15][304] Kathryn McLay is the president and CEO of Sam's Club.[145][305]

Global eCommerce

Based in San Bruno, California, Walmart's Global eCommerce division provides online retailing for Walmart, Sam's Club, Asda, and all other international brands. There are several locations in the United States in California and Oregon: San Bruno, Sunnyvale, Brisbane, and Portland. Locations outside of the United States include Shanghai (China), Leeds (United Kingdom), and Bangalore (India).

Subsidiaries

Private label brands

About 40 percent of products sold in Walmart are private labels, which are produced for the company through contracts with manufacturers. Walmart began offering private label brands in 1991, with the launch of Sam's Choice, a line of drinks produced by Cott Beverages for Walmart. Sam's Choice quickly became popular and by 1993, was the third-most-popular beverage brand in the United States.[306] Other Walmart brands include Great Value and Equate in the U.S. and Canada and Smart Price in Britain. A 2006 study talked of "the magnitude of mind-share Walmart appears to hold in the shoppers' minds when it comes to the awareness of private label brands and retailers."[307]

Entertainment

In 2010, the company teamed with Procter & Gamble to produce Secrets of the Mountain and The Jensen Project, two-hour family movies which featured the characters using Walmart and Procter & Gamble-branded products. The Jensen Project also featured a preview of a product to be released in several months in Walmart stores.[308][309] A third movie, A Walk in My Shoes, also aired in 2010 and a fourth is in production.[310] Walmart's director of brand marketing also serves as co-chair of the Association of National Advertisers's Alliance for Family Entertainment.[311]

Online commerce acquisitions and plans

In September 2016, Walmart purchased e-commerce company Jet.com, founded in 2014 by Marc Lore, to start competing with Amazon.com. Jet.com has acquired its own share of online retailers such as Hayneedle in March 2016, Shoebuy.com in December 2016, and ModCloth in March 2017. Walmart also acquired Parcel, a delivery service in New York, on September 29, 2017.[312][313]

On February 15, 2017, Walmart acquired Moosejaw, an online active outdoor retailer, for approximately $51 million. Moosejaw brought with it partnerships with more than 400 brands, including Patagonia, The North Face, Marmot, and Arc'teryx.[314]

Marc Lore, Walmart's U.S. e-commerce CEO, said that Walmart's existing physical infrastructure of almost 5,000 stores around the U.S. will enhance their digital expansion by doubling as warehouses for e-commerce without increasing overhead.[315] As of 2017, Walmart offers in-store pickup for online orders at 1,000 stores with plans to eventually expand the service to all of its stores.[316]

On May 9, 2018, Walmart announced its intent to acquire a 77% controlling stake in the Indian e-commerce website Flipkart for $16 billion[317] (beating bids by Amazon.com), subject to regulatory approval. Following its completion, the website's management will report to Marc Lore.[318][319][320] Completion of the deal was announced on August 18, 2018.[321]

The company's partnership with subscription service Kidbox was announced on April 16, 2019.[322]

Corporate affairs

Walmart is headquartered in the Walmart Home Office complex in Bentonville, Arkansas. The company's business model is based on selling a wide variety of general merchandise at low prices.[11] Doug McMillon became Walmart's CEO on February 1, 2014. He has also worked as the head of Sam's Club and Walmart International.[323] The company refers to its employees as "associates". All Walmart stores in the U.S. and Canada also have designated "greeters" at the entrance, a practice pioneered by Sam Walton and later imitated by other retailers. Greeters are trained to help shoppers find what they want and answer their questions.[324]

For many years, associates were identified in the store by their signature blue vest, but this practice was discontinued in June 2007 and replaced with khaki pants and polo shirts. The wardrobe change was part of a larger corporate overhaul to increase sales and rejuvenate the company's stock price.[325] In September 2014, the uniform was again updated to bring back a vest (paid for by the company) for store employees over the same polos and khaki or black pants paid for by the employee. The vest is navy blue for Walmart employees at Supercenters and discounts stores, lime green for Walmart Neighborhood Market employees, and yellow for self-check-out associates; door greeters, and customer service managers. All three state "Proud Walmart Associate" on the left breast and the "Spark" logo covering the back.[326] Reportedly one of the main reasons the vest was reintroduced was that some customers had trouble identifying employees.[327] In 2016, self-checkout associates, door greeters and customer service managers began wearing a yellow vest to be better seen by customers. By requiring employees to wear uniforms that are made up of standard "streetwear", Walmart is not required to purchase the uniforms or reimburse employees which are required in some states, as long as that clothing can be worn elsewhere. Businesses are only legally required to pay for branded shirts and pants or clothes that would be difficult to wear outside of work.[328]

Unlike many other retailers, Walmart does not charge slotting fees to suppliers for their products to appear in the store.[329] Instead, it focuses on selling more-popular products and provides incentives for store managers to drop unpopular products.[329]

From 2006 to 2010, the company eliminated its layaway program. In 2011, the company revived its layaway program.[330][331]

Walmart introduced its Site-To-Store program in 2007, after testing the program since 2004 on a limited basis. The program allows walmart.com customers to buy goods online with a free shipping option, and have goods shipped to the nearest store for pickup.[332]

On September 15, 2017, Walmart announced that it would build a new headquarters in Bentonville to replace its current 1971 building and consolidate operations that have spread out to 20 different buildings throughout Bentonville.[333]

According to watchdog group Documented, in 2020 Walmart contributed $140,000 to the Rule of Law Defense Fund, a fund-raising arm of the Republican Attorneys General Association.[334]

Finance and governance

For the fiscal year ending January 31, 2019, Walmart reported net income of US$6.67 billion on $514.405 billion of revenue. The company's international operations accounted for $120.824 billion, or 23.7 percent, of its $510.329 billion of sales.[15][7] Walmart is the world's 29th-largest public corporation, according to the Forbes Global 2000 list, and the largest public corporation when ranked by revenue.[335]

Walmart is governed by an eleven-member board of directors elected annually by shareholders. Gregory B. Penner, son-in-law of S. Robson Walton and the grandson-in-law of Sam Walton, serves as chairman of the board. Doug McMillon serves as president and chief executive officer. Current members of the board are:[336][7][337]

- Gregory B. Penner, chairman of the board of directors of Walmart Inc. and general partner of Madrone Capital Partners

- Cesar Conde, chairman of NBCUniversal International Group and NBCUniversal Telemundo Enterprises

- Timothy P. Flynn, retired CEO of KPMG International

- Sarah Friar, CEO of Nextdoor

- Carla A. Harris, Vice-chairman of Wealth Management, head of multicultural client strategy, managing director, and senior client advisor at Morgan Stanley

- Tom Horton, senior advisor at Warburg Pincus, LLC, and retired chairman and CEO of American Airlines

- Marissa A. Mayer, co-founder of Lumi Labs, Inc., and former president and CEO of Yahoo!, Inc.

- Doug McMillon, president and CEO of Walmart

- Randall Stephenson, retired chairman and CEO of AT&T Inc.

- S. Robson "Rob" Walton, retired chairman of the board of directors of Walmart Inc.

- Steuart Walton, founder of RZC Investments, LLC.

Notable former members of the board include Hillary Clinton (1985–1992)[338] and Tom Coughlin (2003–2004), the latter having served as vice chairman. Clinton left the board before the 1992 U.S. presidential election, and Coughlin left in December 2005 after pleading guilty to wire fraud and tax evasion for stealing hundreds of thousands of dollars from Walmart.[339]

After Sam Walton's death in 1992, Don Soderquist, Chief Operating Officer and Senior Vice Chairman, became known as the "Keeper of the Culture".[340]

| Year | Revenue | Net Income | Total Assets | Price per Share (US$) |

Employees | Stores |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| US$ millions | ||||||

| 1968[341] | 12.618754 | 0.481754 | 24 | |||

| 1969[341] | 21.365081 | 0.605211 | 27 | |||

| 1970[341] | 30.862659 | 1.187764 | 1,000 | 32 | ||

| 1971[342] | 44.286012 | 1.651599 | 15.331 | 1,500 | 38 | |

| 1972[342] | 78.014164 | 2.907354 | 28.463 | 2,300 | 51 | |

| 1973[343] | 124.889141 | 4.591469 | 46.241 | 3,500 | 66 | |

| 1974[344] | 167.560892 | 6.15852 | 60.106 | 4,400 | 78 | |

| 1975[345] | 236.20888 | 6.353336 | 75.221 | 5,800 | 104 | |

| 1976[346] | 340.331 | 11.506 | 125.347 | 7,500 | 125 | |

| 1977[347] | 478.807 | 16.546 | 168.201 | 10,000 | 153 | |

| 1978[348] | 678.456 | 21.886 | 251.865 | 14,700 | 195 | |

| 1979[349] | 900.298 | 29.447 | 324.666 | 17,500 | 229 | |

| 1980[350] | 1,248.976 | 41.151 | 457.879 | 21,000 | 276 | |

| 1981[351] | 1,643.199 | 55.682 | 592.345 | 27,000 | 330 | |

| 1982[352] | 2,444.997 | 82.794 | 937.513 | 41,000 | 491 | |

| 1983[353] | 3,376.252 | 124.14 | 1,187.448 | 46,000 | 551 | |

| 1984[354] | 4,666.909 | 196.244 | 1,652.254 | 62,000 | 645 | |

| 1985[355] | 6,400.861 | 270.767 | 2,205.229 | 81,000 | 758 | |

| 1986[356] | 8,451.489 | 327.437 | 3,103.645 | 104,000 | 887 | |

| 1987[357] | 11,909.076 | 450.086 | 4,049.092 | 141,000 | 1,037 | |

| 1988[358] | 15,959.255 | 627.643 | 5,131.809 | 183,000 | 1,215 | |

| 1989[359] | 20,649.001 | 837.221 | 6,359.668 | 223,000 | 1,381 | |

| 1990[360] | 25,810.656 | 1,075.900 | 8,198.484 | 275,000 | 1,528 | |

| 1991[361] | 32,601.594 | 1,291.024 | 11,388.915 | 328,000 | 1,725 | |

| 1992[362] | 43,886.902 | 1,608.476 | 15,443.389 | 371,000 | 1,930 | |

| 1993[363] | 55,483.771 | 1,994.794 | 20,565.087 | 434,000 | 2,136 | |

| 1994[364] | 67,344.574 | 2,333.277 | 26,440.764 | 528,000 | 2,463 | |

| 1995[365] | 82,494 | 2,681 | 32,819 | 622,000 | 2,872 | |

| 1996[366] | 93,627 | 2,740 | 37,541 | 675,000 | 3,106 | |

| 1997[367] | 104,859 | 3,056 | 39,604 | 728,000 | 3,117 | |

| 1998[368] | 117,958 | 3,526 | 45,384 | 825,000 | 3,406 | |

| 1999[369] | 137,634 | 4,430 | 49,996 | 910,000 | 3,600 | |

| 2000[370] | 165,013 | 5,377 | 70,349 | 38.34 | 1,140,000 | 3,662 |

| 2001[370] | 191,329 | 6,295 | 78,130 | 37.30 | 1,244,000 | 4,189 |

| 2002[371] | 204,011 | 6,592 | 81,549 | 39.93 | 1,383,000 | 4,414 |

| 2003[371] | 229,616 | 7,955 | 92,900 | 39.40 | 1,400,000 | 4,688 |

| 2004[371] | 256,329 | 9,054 | 104,912 | 40.17 | 1,500,000 | 4,906 |

| 2005[372] | 284,310 | 10,267 | 120,154 | 36.03 | 1,700,000 | 5,289 |

| 2006[373] | 312,101 | 11,231 | 138,187 | 34.95 | 1,800,000 | 6,141 |

| 2007[374] | 348,368 | 11,284 | 151,587 | 35.76 | 1,900,000 | 6,779 |

| 2008[375] | 377,023 | 12,731 | 163,514 | 42.74 | 2,100,000 | 7,262 |

| 2009[376] | 404,254 | 13,381 | 163,429 | 40.02 | 2,100,000 | 7,870 |

| 2010[377] | 408,085 | 14,370 | 170,407 | 42.90 | 2,100,000 | 8,416 |

| 2011[378] | 421,849 | 16,389 | 180,782 | 45.11 | 2,100,000 | 8,970 |

| 2012[379] | 446,509 | 15,699 | 193,406 | 57.29 | 2,200,000 | 10,130 |

| 2013[380] | 468,651 | 16,999 | 203,105 | 65.74 | 2,200,000 | 10,773 |

| 2014[381] | 476,294 | 16,022 | 204,751 | 69.17 | 2,200,000 | 10,942 |

| 2015[382] | 485,651 | 16,363 | 203,490 | 66.40 | 2,200,000 | 11,453 |

| 2016[383] | 482,130 | 14,694 | 199,581 | 65.64 | 2,300,000 | 11,528 |

| 2017[384] | 485,873 | 13,643 | 198,825 | 76.67 | 2,300,000 | 11,695 |

| 2018[385] | 500,343 | 9,862 | 204,522 | 90.80 | 2,300,000 | 11,718 |

| 2019[386] | 514,405 | 6,670 | 219,295 | 108.41 | 2,200,000 | 11,361 |

| 2020[387] | 523,964 | 14,881 | 236,495 | 129.60 | 2,200,000 | 11,501 |

| 2021[2] | 559,151 | 13,510 | 252,500 | 2,200,000 | 11,443 | |

Ownership

Walmart Inc. is a Delaware-domiciled joint-stock company registered with the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission, with its registered office located in Wolters Kluwer's Corporation Trust Center in Wilmington. As of March 2017,[388] it has 3,292,377,090 outstanding shares. These are held mainly by the Walton family, a number of institutions and funds.[6][389]

- 43.00% (1,415,891,131): Walton Enterprises LLC

- 5.30% (174,563,205): Walton family Holdings Trust[390]

- 3.32% (102,036,399): The Vanguard Group, Inc

- 2.37% (72,714,226): State Street Corporation

- 1.37% (42,171,892): BlackRock Institutional Trust Company

- 0.94% (28,831,721): Vanguard Total Stock Market Index Fund

- 0.77% (23,614,578): BlackRock Fund Advisors

- 0.71% (21,769,126): Dodge & Cox Inc

- 0.68% (20,978,727): Vanguard 500 Index Fund

- 0.65% (20,125,838): Bank of America Corporation

- 0.57% (17,571,058): Bank of New York Mellon Corporation

- 0.57% (17,556,128): Northern Trust Corporation

- 0.55% (16,818,165): Vanguard Institutional Index Fund-Institutional Index Fund

- 0.55% (16,800,850): State Farm Mutual Automobile Insurance Co

- 0.52% (15,989,827): SPDR S&P 500 ETF Trust

Competition

In North America, Walmart's primary competitors include grocery stores and department stores like Aldi, Lidl, Kmart, Kroger, Ingles, Publix, Target, Harris Teeter, Meijer, and Winn Dixie in the United States; Hudson's Bay, Loblaw retail stores, Sobeys, Metro, and Giant Tiger in Canada; and Comercial Mexicana and Soriana in Mexico. Competitors of Walmart's Sam's Club division are Costco and the smaller BJ's Wholesale Club chain. Walmart's move into the grocery business in the late 1990s set it against major supermarket chains in both the United States and Canada.[391] Studies have typically found that Walmart’s prices are significantly lower than those of their competitors, and that Walmart’s presence is associated with lower food prices for households. Comparisons of performance metrics such as sales per square foot suggest that supermarkets in direct competition with Walmart Supercenters show significant decreases in profit margins, an effect that is strongest in the case of unionized competitors. Between 2000 and 2010, Walmart’s entry into new areas often lowered local food prices at other stores. However, recent studies have not found the same effect, suggesting that retailers may have changed their competitive strategies.[33]

While the idea that Walmart destroys small businesses is widely assumed to be true, research so far suggests that Walmart superstores have little effect on smaller retailers such as "Mom and Pop" businesses. Differences in impact appear to be specific to the goods sold. Small retailers may experience difficulty if they rely on selling products identical to those at Walmart or if they try to sell at lower prices.[33] Dollar stores such as Family Dollar and Dollar General have been able to find a small niche market and compete successfully against Walmart.[391] In 2004, Walmart responded by testing its own dollar store concept, a subsection of some stores called "Pennies-n-Cents".[392][33]

Walmart also had to face fierce competition in some foreign markets. For example, in Germany it had captured just 2 percent of the German food market following its entry into the market in 1997 and remained "a secondary player" behind Aldi with 19 percent.[393] Walmart continues to do well in the UK, where its Asda subsidiary is the second-largest retailer.[394]

In May 2006, after entering the South Korean market in 1998, Walmart sold all 16 of its South Korean outlets to Shinsegae, a local retailer, for US$882 million. Shinsegae re-branded the Walmarts as E-mart stores.[395]

Walmart struggled to export its brand elsewhere as it rigidly tried to reproduce its model overseas. In China, Walmart hopes to succeed by adapting and doing things preferable to Chinese citizens. For example, it found that Chinese consumers preferred to select their own live fish and seafood; stores began displaying the meat uncovered and installed fish tanks, leading to higher sales.[396]

Customer base