West Slavs

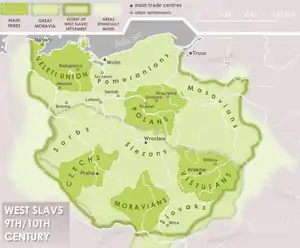

The West Slavs are Slavic peoples who speak the West Slavic languages.[1][2] They separated from the common Slavic group around the 7th century, and established independent polities in Central Europe by the 8th to 9th centuries.[1] The West Slavic languages diversified into their historically attested forms over the 10th to 14th centuries.[3]

Słowianie Zachodni (Polish) Západní Slované (Czech) Západní Slovania (Slovak) Zôpôdni Słowiónie (Kashubian) Pódwjacorne Słowjany (Lower Sorbian) Zapadni Słowjenjo (Upper Sorbian) | |

|---|---|

Countries where other Slavic languages are the national language | |

| Total population | |

| see #Population | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| Central Europe, historically Western Europe (modern-day Eastern Germany) | |

| Religion | |

| Catholicism (Poles, Slovaks, Silesians, Kashubians, Moravians and Sorbs and minority among Czechs) Protestantism (minority among Sorbs) Irreligion (majority among Czechs) | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Other Slavs |

Today, groups which speak West Slavic languages include the Poles, Czechs, Slovaks, and Sorbs.[4][5][6] From the twelfth century onwards, most West Slavs converted to Roman Catholicism, thus coming under the cultural influence of the Latin Church, adopting the Latin alphabet, and tending to be more closely integrated into cultural and intellectual developments in western Europe than the East Slavs, who converted to Orthodox Christianity and adopted the Cyrillic alphabet.[7][8]

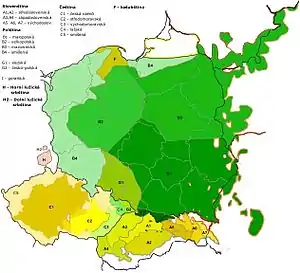

Linguistically, the West Slavic group can be divided into three subgroups: Lechitic, including Polish, Kashubian and the extinct Polabian and Pomeranian languages as well as Lusatian (Sorbian) and Czecho-Slovak.[9]

History

In the Middle Ages, the name "Wends" (probably derived from the Roman-era Veneti) may have applied to Slavic peoples.[1] However, sources such as the Chronicle of Fredegar and Paul the Deacon are neither clear nor consistent in their ethnographic terminology, and whether "Wends" or "Veneti" refer to Slavic people, pre-Slavic people, or to a territory rather than a population, is a matter of scholarly debate.[10]

The early Slavic expansion began in the 5th century, and by the 6th century, the groups that would become the West, East and South Slavic groups had probably become geographically separated. Early modern historiographers such as Penzel (1777) and Palacky (1827) have claimed Samo's 'kingdom' to be first independent Slavic state in history by taking Fredegar's Wendish account at face value.[11] Curta (1997) argued that the text is not as straightforward: according to Fredegar, Wends were a gens, Sclavini merely a genus, and there was no 'Slavic' gens.[12] '...'Wends' occur particularly in political contexts: the Wends, not the Slavs, made Samo their king.'[13] Other such alleged early West Slavic states include the Principality of Moravia (8th century–833), the Principality of Nitra (8th century–833) and Great Moravia (833–c. 907). Christiansen (1997) identified the following West Slav tribes in the 11th century from 'the coastlands and hinterland from the aby of Kiel to the Vistula, including the islands of Fehmarn, Poel, Rügen, Usedom and Wollin', namely the Wagrians, Obodrites (or Abotrites), the Polabians, the Liutizians or Wilzians, the Rugians or Rani, the Sorbs, the Lusatians, the Poles, and the Pomeranians (later divided into Pomerelians and Cassubians).[14] They came under the domination of the Holy Roman Empire after the Wendish Crusade in the Middle Ages and had been strongly Germanized by Germans at the end of the 19th century. The Polabian language survived until the beginning of the 19th century in what is now the German state of Lower Saxony.[15]

Groupings

Various attempts have been made to group the West Slavs into subgroups according to various criteria, including geography, historical tribes, and linguistics.

Bavarian Geographer grouping

In 845 the Bavarian Geographer made a list of West Slavic tribes who lived in the areas of modern-day Poland, Czech Republic, Germany and Denmark:[16]

| Pos. | Latin name in 845 | English name | no. of gords |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Nortabtrezi | North Obotrites | 53 |

| 2 | Uuilci | Veleti | 95 |

| 7 | Hehfeldi | Hevellians | 8 |

| 14 | Osterabtrezi | East Obotrites | 100 |

| 15 | Miloxi | Milceni[16] | 67 |

| 16 | Phesnuzi | Besunzane[16] | 70 |

| 17 | Thadesi | Dadosesani[16] | 200 |

| 18 | Glopeani | Goplans | 400 |

| 33 | Lendizi | Lendians | 98 |

| 34 | Thafnezi | / | 257 |

| 36 | Prissani | Prissani | 70 |

| 37 | Uelunzani | Wolinians | 70 |

| 38 | Bruzi | / | |

| 48 | Uuislane | Vistulans | / |

| 49 | Sleenzane | Silesians | 15 |

| 50 | Lunsizi | Sorbs | 30 |

| 51 | Dadosesani | Thadesi[16] | 20 |

| 52 | Milzane | Milceni | 30 |

| 53 | Besunzane | Phesnuzi[16] | 2 |

| 56 | Lupiglaa | Łupigoła[16] | 30 |

| 57 | Opolini | Opolans | 20 |

| 58 | Golensizi | Golensizi | 5 |

Tribal grouping

- Lechitic group[17]

- Poles

- Masovians

- Polans

- Lendians

- Vistulans

- Silesians

- Pomeranians[17]

- Slovincians

- Polabians[17]

- Obodrites/Abodrites

- Obotrites proper

- Wagrians

- Warnower

- Polabians proper

- Linonen

- Travnjane

- Drevani

- Veleti (Wilzi), succeeded by Lutici (Liutici)

- Kissini (Kessiner, Chizzinen, Kyzziner)

- Circipani (Zirzipanen)

- Tollensians

- Redarier

- Ucri (Ukr(an)i, Ukranen)

- Rani (Rujani)

- Hevelli (Stodorani)

- Volinians (Velunzani)

- Pyritzans (Prissani)

- Obodrites/Abodrites

- Czech–Slovak group

- Czechs

- Moravians

- Slovaks

- Sorbian group[17]

- Milceni (Upper Sorbs)

- Lusatian Sorbs (Lower Sorbs)

Population

See also

- Slavic peoples

- List of Slavic studies journals

- Czechization

- Magyarization

- Polonization

- Slovakization

- East Slavs

- South Slavs

References

- Ilya Gavritukhin, Vladimir Petrukhin (2015). Yury Osipov (ed.). Slavs. Great Russian Encyclopedia (in 35 vol.) Vol. 30. pp. 388–389.

- Gołąb, Zbigniew (1992). The Origins of the Slavs: A Linguist's View. Columbus, Ohio: Slavica Publishers. pp. 12–13.

The present-day Slavic peoples are usually divided into the three following groups: West Slavic, East Slavic, and South Slavic. This division has both linguistic and historico-geographical justification, in the sense that on the one hand the respective Slavic languages show some old features which unite them into the above three groups, and on the other hand the pre- and early historical migrations of the respective Slavic peoples distributed them geographically in just this way.

- Sergey Skorvid (2015). Yury Osipov (ed.). Slavic languages. Great Russian Encyclopedia (in 35 vol.) Vol. 30. pp. 396–397–389.

- Butcher, Charity (2019). The handbook of cross-border ethnic and religious affinities. London. p. 90. ISBN 9781442250222.

- Vico, Giambattista (2004). Statecraft : the deeds of Antonio Carafa = (De rebus gestis Antonj Caraphaei). New York: P. Lang. p. 374. ISBN 9780820468280.

- Hart, Anne (2003). The beginner's guide to interpreting ethnic DNA origins for family history : how Ashkenazi, Sephardi, Mizrahi & Europeans are related to everyone else. New York, N.Y.: iUniverse. p. 57. ISBN 9780595283064.

- Wiarda, Howard J. (2013). Culture and foreign policy : the neglected factor in international relations. Burlington, Vt.: Ashgate. p. 39. ISBN 9781317156048.

- Dunn, Dennis J. (2017). The Catholic Church and Soviet Russia, 1917-39. New York. pp. 8–9. ISBN 9781315408859.

- Bohemia and Poland. Chapter 20.pp 512-513. [in:] Timothy Reuter. The New Cambridge Medieval History: c. 900-c.1024. 2000

- Curta 1997, p. 141–144, 152–153.

- Curta 1997, p. 143.

- Curta 1997, p. 152–153.

- Curta 1997, p. 152.

- Christiansen, Erik (1997). The Northern Crusades. London: Penguin Books. p. 41. ISBN 0-14-026653-4.

- Polabian language

- Krzysztof Tomasz Witczak (2013). "Poselstwo ruskie w państwie niemieckim w roku 839: Kulisy śledztwa w świetle danych Geografa Bawarskiego". Slavia Orientalis (in Polish and English). 62 (1): 25–43.

- Jerzy Strzelczyk. Bohemia and Poland: two examples of successful western Slavonic state-formation. In: Timothy Reuter ed. The New Cambridge Medieval History: c. 900-c. 1024. Cambridge University Press. 1995. p. 514.

Bibliography

- Gołąb, Zbigniew (1992). The Origins of the Slavs: A Linguist's View. Columbus, Ohio: Slavica Publishers. pp. 12–13.

- Curta, Florin (1997). "Slavs in Fredegar and Paul the Deacon: medieval gens or 'scourge of God'?" (PDF). Early Medieval Europe. Blackwell Publishers. 6 (2): 141–167. doi:10.1111/1468-0254.00009. S2CID 162269231. Retrieved 17 August 2022.

While being traditionally regarded, at least in Polish historiography, as forefathers of the western Slavs, and therefore successors of the Veneti mentioned by Pliny, Tacitus, or Claudius Ptolemaeus, recent studies argue that the name may have not been a self-designation. By calling the Slavs 'Wends', German-speaking groups may have alluded to a pre-Slavic population. It is, however, not clear how an ancient terminology came to be used in the case of the early medieval Slavs. (...) [There may be] a meaning behind Fredegar's presumably inconsistent ethnic vocabulary. Perhaps 'Wends' and 'Sclavenes' are meant to denote a specific social and political configuration, in which such concepts as 'state' or 'ethnicity' are relevant, while 'Slavs' is a more general term, used in a territorial rather than an ethnic sense; Samo as a merchant went in Sclauos to do business...

- Sergey Skorvid (2015). Yury Osipov (ed.). Slavic languages. Great Russian Encyclopedia (in 35 vol.) Vol. 30. pp. 396–397–389.

- Ilya Gavritukhin, Vladimir Petrukhin (2015). Yury Osipov (ed.). Slavs. Great Russian Encyclopedia (in 35 vol.) Vol. 30. pp. 388–389.