Winter wren

The winter wren (Troglodytes hiemalis) is a very small North American bird and a member of the mainly New World wren family Troglodytidae. It was once lumped with the Pacific wren (Troglodytes pacificus) of western North America and the Eurasian wren (Troglodytes troglodytes) of Eurasia under the name winter wren.

| Winter wren | |

|---|---|

.jpg.webp) | |

| In Prospect Park, New York. | |

| Song recorded in Tahquamenon Falls State Park, Michigan | |

Conservation status | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Aves |

| Order: | Passeriformes |

| Family: | Troglodytidae |

| Genus: | Troglodytes |

| Species: | T. hiemalis |

| Binomial name | |

| Troglodytes hiemalis Viellot, 1819 | |

| |

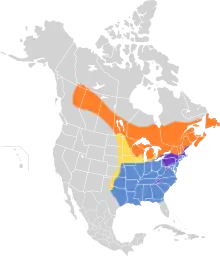

Breeding

Migration

Year-round

Nonbreeding | |

| Synonyms | |

|

Olbiorchilus hiemalis | |

It breeds in coniferous forests from British Columbia to the Atlantic Ocean. It migrates through and winters across southeastern Canada, the eastern half the United States and (rarely) north-eastern Mexico. Small numbers may be casual in the western United States and Canada.

The scientific name is taken from the Greek word troglodytes (from "trogle" a hole, and "dyein" to creep), meaning "cave-dweller", and refers to its habit of disappearing into cavities or crevices while hunting arthropods or to roost.

Taxonomy

The winter wren was described and illustrated in 1808 by the American ornithologist Alexander Wilson. He was uncertain as to whether the wren should be considered as a separate species or as a subspecies of the Eurasian wren.[2] When the French Louis Jean Pierre Vieillot described the winter wren in 1819 he considered it as a separate species and coined the current binomial name Troglodytes hiemalis.[3] The specific epithet is Latin and means "of winter".[4] The type locality was restricted to Nova Scotia by Harry C. Oberholser in 1902.[5][6]

The winter wren was formerly considered to be conspecific with the Eurasian wren (Troglodytes troglodytes) and the Pacific wren (Troglodytes pacificus).[7][8] The Eurasian wren was split from the two North American species based on a study of mitochondrial DNA published in 2007.[9] A study published in 2008 of the songs and genetics of individuals in an overlap zone between Troglodytes hiemalis and Troglodytes pacificus found strong evidence of reproductive isolation between the two. It was suggested that the pacificus subspecies be promoted to the species level designation of Troglodytes pacificus with the common name of "Pacific wren".[10] By applying a molecular clock to the amount of mitochondrial DNA sequence divergence between the two, it was estimated that Troglodytes pacificus and Troglodytes troglodytes last shared a common ancestor approximately 4.3 million years ago, long before the glacial cycles of the Pleistocene, which are thought to have promoted speciation in many avian systems inhabiting the boreal forest of North America.[10][11]

Two subspecies are recognised:[7]

- T. h. hiemalis Vieillot, 1819 – breeds in east Canada and northeast USA, winters in southeast USA

- T. h. pullus (Burleigh, 1935) – breeds in mountains of West Virginia to Georgia (east-central USA), winters in south USA

Description

Small tail is often cocked above its back, and short neck gives the appearance of a small brown ball. Rufous brown above, grayer below, barred with darker brown and gray, even on wings and tail. The bill is dark brown, the legs pale brown. Young birds are less distinctly barred. Most are identifiable by the pale "eyebrows" over their eyes.

Measurements:[12]

- Length: 3.1–4.7 in (7.9–11.9 cm)

- Weight: 0.3–0.4 oz (8.5–11.3 g)

- Wingspan: 4.7–6.3 in (12–16 cm)

Distribution and habitat

The winter wren nests mostly in coniferous forests, especially those of spruce and fir, where it is often identified by its long and exuberant song. Although it is an insectivore, it can remain in moderately cold and even snowy climates by foraging for insects on substrates such as bark and fallen logs.

Its movements as it creeps or climbs are incessant rather than rapid; its short flights swift and direct but not sustained, its tiny round wings whirring as it flies from bush to bush.

At night, usually in winter, it often roosts, true to its scientific name, in dark retreats, snug holes and even old nests. In hard weather it may do so in parties, either consisting of the family or of many individuals gathered together for warmth.

Behavior and ecology

.jpg.webp)

Breeding

The male builds a small number of nests. These are called "cock nests" but are never lined until the female chooses one to use. The normal round nest of grass, moss, lichens or leaves is tucked into a hole in a wall, tree trunk, crack in a rock or corner of a building, but it is often built in bushes, overhanging boughs or the litter which accumulates in branches washed by floods. Five to eight white or slightly speckled eggs are laid in April, and second broods are reared.

References

- BirdLife International (2016). "Troglodytes hiemalis". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2016: e.T103885731A104334569. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2016-3.RLTS.T103885731A104334569.en. Retrieved 18 November 2021.

- Wilson, Alexander (1808). American Ornithology; or, the Natural History of the Birds of the United States: Illustrated with Plates Engraved and Colored from Original drawings taken from Nature. Vol. 3. Philadelphia: Bradford and Inskeep. p. 139, Plate 8 fig. 6.

- Vieillot, Louis Jean Pierre (1819). Nouveau dictionnaire d'histoire naturelle, appliquée aux arts, à l'agriculture, à l'économie rurale et domestique, à la médecine, etc (in French). Vol. 34 (Nouvelle édition ed.). Paris: Deterville. p. 514.

- Jobling, James A. (2010). The Helm Dictionary of Scientific Bird Names. London: Christopher Helm. p. 192. ISBN 978-1-4081-2501-4.

- Oberholser, Harry C. (1902). "A synopsis of the genus commonly called Anorthura". Auk. 19: 175–181 [178].

- Mayr, Ernst; Greenway, James C. Jr, eds. (1960). Check-list of Birds of the World. Vol. 9. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Museum of Comparative Zoology. p. 415.

- Gill, Frank; Donsker, David; Rasmussen, Pamela, eds. (January 2022). "Dapple-throats, sugarbirds, fairy-bluebirds, kinglets, hyliotas, wrens & gnatcatchers". IOC World Bird List Version 12.1. International Ornithologists' Union. Retrieved 28 May 2022.

- Chesser, R Terry; Banks, Richard C; Barker, F Keith; Cicero, Carla; Dunn, Jon L; Kratter, Andrew W; Lovette, Irby J; Rasmussen, Pamela C; Remsen, JV Jr; Rising, James D; Stotz, Douglas F; Winker, Kevin (2010). "Fifty-First Supplement to the American Ornithologists' Union Check-List of North American Birds". The Auk. 127 (3): 726–744 [734–735]. doi:10.1525/auk.2010.127.4.966.

- Drovetski, S.V.; Zink, R.M.; Rohwer, S.; Fadeev, I.V.; Nesterov, E.V.; Karagodin, I.; Koblik, E.A.; Red'kin, Y.A. (2004). "Complex biogeographic history of a Holarctic passerine". Proceedings of the Royal Society of London. Series B: Biological Sciences. 271 (1538): 545–551. doi:10.1098/rspb.2003.2638.

- Toews, David P.L.; Irwin, Darren E. (2008). "Cryptic speciation in a Holarctic passerine revealed by genetic and bioacoustic analyses". Molecular Ecology. 17 (11): 2691–2705. doi:10.1111/j.1365-294X.2008.03769.x.

- Weir, J.T.; Schluter, D. (2004). "Ice sheets promote speciation in boreal birds". Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 271 (1551): 1881–1887. doi:10.1098/rspb.2004.2803.

- "Winter Wren Identification, All About Birds, Cornell Lab of Ornithology". www.allaboutbirds.org. Retrieved 2020-09-28.

External links

- Identification tips - USGS Patuxent Bird Identification InfoCenter

- Species account – Cornell Lab of Ornithology

- "Northern wren media". Internet Bird Collection.

- Winter wren photo gallery at VIREO (Drexel University)

- Interactive range map of Troglodytes hiemalis at IUCN Red List maps