Occupational safety and health

Occupational safety and health (OSH), also commonly referred to as occupational health and safety (OHS), occupational health,[1] or occupational safety, is a multidisciplinary field concerned with the safety, health, and welfare of people at work (i.e. in an occupation). These terms also refer to the goals of this field,[2] so their use in the sense of this article was originally an abbreviation of occupational safety and health program/department etc.

_(Art._IWM_LD_2850).jpg.webp)

| Part of a series on |

| Organised labour |

|---|

|

| Part of a series on |

| Public health |

|---|

|

|

|

The goal of an occupational safety and health program is to foster a safe and healthy occupational environment.[3][4] OSH also protects all the general public who may be affected by the occupational environment.[5]

Globally, more than 2.78 million people die annually as a result of workplace-related accidents or diseases, corresponding to one death every fifteen seconds. There are an additional 374 million non-fatal work-related injuries annually. It is estimated that the economic burden of occupational-related injury and death is nearly four per cent of the global gross domestic product each year.[6] The human cost of this adversity is enormous.

In common-law jurisdictions, employers have the common law duty (also called duty of care) to take reasonable care of the safety of their employees.[7] Statute law may, in addition, impose other general duties, introduce specific duties, and create government bodies with powers to regulate occupational safety issues: details of this vary from jurisdiction to jurisdiction.

Definition

As defined by the World Health Organization (WHO) "occupational health deals with all aspects of health and safety in the workplace and has a strong focus on primary prevention of hazards."[8] Health has been defined as "a state of complete physical, mental and social well-being and not merely the absence of disease or infirmity."[9] Occupational health is a multidisciplinary field of healthcare concerned with enabling an individual to undertake their occupation, in the way that causes least harm to their health. It aligns with the promotion of health and safety at work, which is concerned with preventing harm from hazards in the workplace.

Since 1950, the International Labour Organization (ILO) and the WHO have shared a common definition of occupational health. It was adopted by the Joint ILO/WHO Committee on Occupational Health at its first session in 1950 and revised at its twelfth session in 1995. The definition reads:

"The main focus in occupational health is on three different objectives: (i) the maintenance and promotion of workers' health and working capacity; (ii) the improvement of working environment and work to become conducive to safety and health and (iii) development of work organizations and working cultures in a direction which supports health and safety at work and in doing so also promotes a positive social climate and smooth operation and may enhance productivity of the undertakings. The concept of working culture is intended in this context to mean a reflection of the essential value systems adopted by the undertaking concerned. Such a culture is reflected in practice in the managerial systems, personnel policy, principles for participation, training policies and quality management of the undertaking."

— Joint ILO/WHO Committee on Occupational Health[10]

Those in the field of occupational health come from a wide range of disciplines and professions including medicine, psychology, epidemiology, physiotherapy and rehabilitation, occupational medicine, human factors and ergonomics, and many others. Professionals advise on a broad range of occupational health matters. These include how to avoid particular pre-existing conditions causing a problem in the occupation, correct posture for the work, frequency of rest breaks, preventive action that can be undertaken, and so forth. The quality of occupational safety is characterized by (1) the indicators reflecting the level of industrial injuries, (2) the average number of days of incapacity for work per employer, (3) employees' satisfaction with their work conditions and (4) employees' motivation to work safely.[11]

"Occupational health should aim at: the promotion and maintenance of the highest degree of physical, mental and social well-being of workers in all occupations; the prevention amongst workers of departures from health caused by their working conditions; the protection of workers in their employment from risks resulting from factors adverse to health; the placing and maintenance of the worker in an occupational environment adapted to his physiological and psychological capabilities; and, to summarize, the adaptation of work to man and of each man to his job.

Given the high demand in society for health and safety provisions at work based on reliable information, occupational safety and health (OSH) professionals should find their roots in evidence-based practice. A new term is "evidence-informed decision making". A working definition of evidence-based practice could be: evidence-based practice is the use of evidence from literature, and other evidence-based sources, for advice and decisions that favor the health, safety, well-being, and work ability of workers. Therefore, evidence-based information must be integrated with professional expertise and the workers' values. Contextual factors must be considered related to legislation, culture, financial, and technical possibilities. Ethical considerations should be heeded.[12]

History

The research and regulation of occupational safety and health are a relatively recent phenomenon. As labor movements arose in response to worker concerns in the wake of the industrial revolution, worker's health entered consideration as a labor-related issue.

In 1700, De Morbis Artificum Diatriba outlined the health hazards of chemicals, dust, metals, repetitive or violent motions, odd postures, and other disease-causative agents encountered by workers in more than fifty occupations. In the United Kingdom, the Factory Acts of the early nineteenth century (from 1802 onwards) arose out of concerns about the poor health of children working in cotton mills: the Act of 1833 created a dedicated professional Factory Inspectorate.[13] : 41 The initial remit of the Inspectorate was to police restrictions on the working hours in the textile industry of children and young persons (introduced to prevent chronic overwork, identified as leading directly to ill-health and deformation, and indirectly to a high accident rate). However, on the urging of the Factory Inspectorate, a further Act in 1844 giving similar restrictions on working hours for women in the textile industry introduced a requirement for machinery guarding (but only in the textile industry, and only in areas that might be accessed by women or children).[13] : 85

In 1840 a Royal Commission published its findings on the state of conditions for the workers of the mining industry that documented the appallingly dangerous environment that they had to work in and the high frequency of accidents. The commission sparked public outrage which resulted in the Mines Act of 1842. The act set up an inspectorate for mines and collieries which resulted in many prosecutions and safety improvements, and by 1850, inspectors were able to enter and inspect premises at their discretion.[14]

Otto von Bismarck inaugurated the first social insurance legislation in 1883 and the first worker's compensation law in 1884 – the first of their kind in the Western world. Similar acts followed in other countries, partly in response to labor unrest.[15]

Workplace hazards

Although work provides many economic and other benefits, a wide array of workplace hazards (also known as unsafe working conditions) also present risks to the health and safety of people at work. These include but are not limited to, "chemicals, biological agents, physical factors, adverse ergonomic conditions, allergens, a complex network of safety risks," and a broad range of psychosocial risk factors.[16] Personal protective equipment can help protect against many of these hazards.[17] A landmark study conducted by the World Health Organization and the International Labour Organization found that exposure to long working hours is the occupational risk factor with the largest attributable burden of disease, i.e. an estimated 745,000 fatalities from ischemic heart disease and stroke events in 2016.[18] This makes overwork the globally leading occupational health risk factor.[19]

Physical hazards affect many people in the workplace. Occupational hearing loss is the most common work-related injury in the United States, with 22 million workers exposed to hazardous noise levels at work and an estimated $242 million spent annually on worker's compensation for hearing loss disability.[20] Falls are also a common cause of occupational injuries and fatalities, especially in construction, extraction, transportation, healthcare, and building cleaning and maintenance.[21] Machines have moving parts, sharp edges, hot surfaces and other hazards with the potential to crush, burn, cut, shear, stab or otherwise strike or wound workers if used unsafely.[22]

Biological hazards (biohazards) include infectious microorganisms such as viruses, bacteria and toxins produced by those organisms such as anthrax. Biohazards affect workers in many industries; influenza, for example, affects a broad population of workers.[23] Outdoor workers, including farmers, landscapers, and construction workers, risk exposure to numerous biohazards, including animal bites and stings,[24][25][26] urushiol from poisonous plants,[27] and diseases transmitted through animals such as the West Nile virus and Lyme disease.[28][29] Health care workers, including veterinary health workers, risk exposure to blood-borne pathogens and various infectious diseases,[30][31] especially those that are emerging.[32]

Dangerous chemicals can pose a chemical hazard in the workplace. There are many classifications of hazardous chemicals, including neurotoxins, immune agents, dermatologic agents, carcinogens, reproductive toxins, systemic toxins, asthmagens, pneumoconiotic agents, and sensitizers.[33] Authorities such as regulatory agencies set occupational exposure limits to mitigate the risk of chemical hazards.[34] International investigations are ongoing into the health effects of mixtures of chemicals, given that toxins can interact synergistically instead of merely additively. For example, there is some evidence that certain chemicals are harmful at low levels when mixed with one or more other chemicals. Such synergistic effects may be particularly important in causing cancer. Additionally, some substances (such as heavy metals and organohalogens) can accumulate in the body over time, thereby enabling small incremental daily exposures to eventually add up to dangerous levels with little overt warning.[35]

Psychosocial hazards include risks to the mental and emotional well-being of workers, such as feelings of job insecurity, long work hours, and poor work-life balance.[36] A recent Cochrane review – using moderate quality evidence – related that the addition of work-directed interventions for depressed workers receiving clinical interventions reduces the number of lost work days as compared to clinical interventions alone.[37] This review also demonstrated that the addition of cognitive behavioral therapy to primary or occupational care and the addition of a "structured telephone outreach and care management program" to usual care are both effective at reducing sick leave days.[37]

By industry

Specific occupational safety and health risk factors vary depending on the specific sector and industry. Construction workers might be particularly at risk of falls, for instance, whereas fishermen might be particularly at risk of drowning. The United States Bureau of Labor Statistics identifies the fishing, aviation, lumber, metalworking, agriculture, mining and transportation industries as among some of the more dangerous for workers.[38] Similarly psychosocial risks such as workplace violence are more pronounced for certain occupational groups such as health care employees, police, correctional officers and teachers.[39]

Construction

Construction is one of the most dangerous occupations in the world, incurring more occupational fatalities than any other sector in both the United States and in the European Union.[40][41] In 2009, the fatal occupational injury rate among construction workers in the United States was nearly three times that for all workers.[40] Falls are one of the most common causes of fatal and non-fatal injuries among construction workers.[40] Proper safety equipment such as harnesses and guardrails and procedures such as securing ladders and inspecting scaffolding can curtail the risk of occupational injuries in the construction industry.[42] Due to the fact that accidents may have disastrous consequences for employees as well as organizations, it is of utmost importance to ensure health and safety of workers and compliance with HSE construction requirements. Health and safety legislation in the construction industry involves many rules and regulations. For example, the role of the Construction Design Management (CDM) Coordinator as a requirement has been aimed at improving health and safety on-site.[43]

The 2010 National Health Interview Survey Occupational Health Supplement (NHIS-OHS) identified work organization factors and occupational psychosocial and chemical/physical exposures which may increase some health risks. Among all U.S. workers in the construction sector, 44% had non-standard work arrangements (were not regular permanent employees) compared to 19% of all U.S. workers, 15% had temporary employment compared to 7% of all U.S. workers, and 55% experienced job insecurity compared to 32% of all U.S. workers. Prevalence rates for exposure to physical/chemical hazards were especially high for the construction sector. Among nonsmoking workers, 24% of construction workers were exposed to secondhand smoke while only 10% of all U.S. workers were exposed. Other physical/chemical hazards with high prevalence rates in the construction industry were frequently working outdoors (73%) and frequent exposure to vapors, gas, dust, or fumes (51%).[44]

Agriculture

Agriculture workers are often at risk of work-related injuries, lung disease, noise-induced hearing loss, skin disease, as well as certain cancers related to chemical use or prolonged sun exposure. On industrialized farms, injuries frequently involve the use of agricultural machinery. The most common cause of fatal agricultural injuries in the United States is tractor rollovers, which can be prevented by the use of roll over protection structures which limit the risk of injury in case a tractor rolls over.[45] Pesticides and other chemicals used in farming can also be hazardous to worker health,[46] and workers exposed to pesticides may experience illnesses or birth defects.[47] As an industry in which families, including children, commonly work alongside their families, agriculture is a common source of occupational injuries and illnesses among younger workers.[48] Common causes of fatal injuries among young farm worker include drowning, machinery and motor vehicle-related accidents.[49]

The 2010 NHIS-OHS found elevated prevalence rates of several occupational exposures in the agriculture, forestry, and fishing sector which may negatively impact health. These workers often worked long hours. The prevalence rate of working more than 48 hours a week among workers employed in these industries was 37%, and 24% worked more than 60 hours a week.[50] Of all workers in these industries, 85% frequently worked outdoors compared to 25% of all U.S. workers. Additionally, 53% were frequently exposed to vapors, gas, dust, or fumes, compared to 25% of all U.S. workers.[51]

Service sector

As the number of service sector jobs has risen in developed countries, more and more jobs have become sedentary, presenting a different array of health problems than those associated with manufacturing and the primary sector. Contemporary problems such as the growing rate of obesity and issues relating to occupational stress, workplace bullying, and overwork in many countries have further complicated the interaction between work and health.

According to data from the 2010 NHIS-OHS, hazardous physical/chemical exposures in the service sector were lower than national averages. On the other hand, potentially harmful work organization characteristics and psychosocial workplace exposures were relatively common in this sector. Among all workers in the service industry, 30% experienced job insecurity in 2010, 27% worked non-standard shifts (not a regular day shift), 21% had non-standard work arrangements (were not regular permanent employees).[52]

Due to the manual labour involved and on a per employee basis, the US Postal Service, UPS and FedEx are the 4th, 5th and 7th most dangerous companies to work for in the US.[53]

Mining and oil and gas extraction

The mining industry still has one of the highest rates of fatalities of any industry.[54] There are a range of hazards present in surface and underground mining operations. In surface mining, leading hazards include such issues as geological stability,[55] contact with plant and equipment, blasting, thermal environments (heat and cold), respiratory health (Black Lung)[56] In underground mining operations hazards include respiratory health, explosions and gas (particularly in coal mine operations), geological instability, electrical equipment, contact with plant and equipment, heat stress, inrush of bodies of water, falls from height, confined spaces. ionising radiation[57]

According to data from the 2010 NHIS-OHS, workers employed in mining and oil and gas extraction industries had high prevalence rates of exposure to potentially harmful work organization characteristics and hazardous chemicals. Many of these workers worked long hours: 50% worked more than 48 hours a week and 25% worked more than 60 hours a week in 2010. Additionally, 42% worked non-standard shifts (not a regular day shift). These workers also had high prevalence of exposure to physical/chemical hazards. In 2010, 39% had frequent skin contact with chemicals. Among nonsmoking workers, 28% of those in mining and oil and gas extraction industries had frequent exposure to secondhand smoke at work. About two-thirds were frequently exposed to vapors, gas, dust, or fumes at work.[58]

Healthcare and social assistance

Healthcare workers are exposed to many hazards that can adversely affect their health and well-being.[59] Long hours, changing shifts, physically demanding tasks, violence, and exposures to infectious diseases and harmful chemicals are examples of hazards that put these workers at risk for illness and injury. Musculoskeletal injury (MSI) is the most common health hazard in for healthcare workers and in workplaces overall.[60] Injuries can be prevented by using proper body mechanics.[61]

According to the Bureau of Labor statistics, U.S. hospitals recorded 253,700 work-related injuries and illnesses in 2011, which is 6.8 work-related injuries and illnesses for every 100 full-time employees.[62] The injury and illness rate in hospitals is higher than the rates in construction and manufacturing – two industries that are traditionally thought to be relatively hazardous.

Occupational exposures in dentistry

Dental professionals and their teams encounter multiple exposures daily to occupational hazards in dentistry.[63] These occupational exposures are detrimental to their health, especially when they are chronic in nature.[63]

- Exposure to noise: Any undesirable sound present in the working environment is referred to as occupational noise.[63] According to the OSHA, when working five days a week in any environment, the international standard of the eight-hour daily occupational exposure should not be greater than 85 decibels (dBA), and anything above this could cause noise-induced hearing loss.[63] Hearing loss due to irreversible injury to the inner ear from chronic, cumulative exposure to loud sounds is called noise-induced hearing loss (NIHL).[64] Buzzing and ringing of the ear, also called tinnitus, and dulled hearing are symptoms of NIHL.[64] Several health problems arise due to overexposure to loud noises such as stress, disruption in sleep patterns, cardiovascular disorders, anxiety, fatigue, and depression.[64] Dental professionals are exposed to noise generated by a wide variety of instruments like ultrasonic scalers, suction, and air rotor handpieces.[64] The recommended maximum exposure limit to sound in an 8-hour workday is 85 dBA.[64] In a study, unobstructed suction noise levels had a range of 75–79 dBA, while obstructed suction had a noise level of 96 dBA, and it was recommended that professionals should not have an exposure of more than 1 hour in such a workplace.[64] High-intensity sounds from ultrasonic scalers range between 69 and 84 dBA within the safe 8-hour limit for occupational noise.[63][64] Threshold shift, the reduction in hearing due to reduced sensitivity level of ears due to noise exposure, occurs due to the use of an ultrasonic scaler, and although this is found to last between 16 hours to almost 2 days, it could cause irreversible damage.[64] In a study conducted in the Dental School of Prince of Songkla University, Thailand, noise annoyance in the dental clinic has been reported by 80% of dental students.[65] The highest percentage of noise dose exposure is found in clinics for pediatric patients.[65]

- Exposure to inhalational anesthetics: Several inhalational anesthetic agents are used in dentistry nowadays like isoflurane, sevoflurane, desflurane, and halothane.[66] But we are most concerned about gaseous sedative, nitrous oxide.[66] Long-term exposures to nitrous oxide may lead to adverse effects on human health such as infertility, neurologic disorders, blood disorders, and spontaneous abortion.[67][68] Researchers believe that when operating rooms without proper ventilation systems have high non-scavenged gas exposures, the risk of spontaneous abortion increases.[68] It is found that despite intact scavenging systems in dental clinics, sometimes nitrous oxide exposure exceeds the NIOSH recommended limit of 25 ppm by more than 40 times.[69] NIOSH advises dental professionals to use additional ventilation or increase air circulation in the operating rooms to tackle the high nitrous oxide exposure.[69]

- Exposure to elemental mercury: The most likely source of exposure to elemental mercury for dental professionals is mercury release in dental amalgam restorations.[70] Due to prolonged practice in the field of dentistry and working with amalgam there is a significant exposure to mercury among professionals.[71] Inhalation of Hg leads to its absorption in the lungs and accumulation in kidneys, and evidence suggests that dental professionals have higher urinary mercury levels.[70][71] About 84.9% of dental practitioners among those attending a health screening program in the annual ADA session in San Francisco, California, were found to restore teeth with 1-200 dental amalgam restorations in a week, and about 4.2% did a minimum of 50 dental amalgam fillings in a week.[71] Minute quantities of elemental mercury elevate the Hg concentrations in dental clinics, such that it poses threat to human health.[70] Mercury vapors and elemental mercury remain in furniture, floors, clothes for years if not cleaned properly, and contribute to being a chronic source of exposure.[70] The limit for elemental mercury vapor in workplaces is 0.05 mg/m3 as recommended by OSHA, especially for workers working 40 hours in a week for 8 hours per day, and that for elemental mercury vapor in workplaces set by NIOSH is 0.05 mg/m3 for a work shift of 10 hours.[70] Inhaling elemental mercury vapors lead to serious health consequences in humans.[70] Acute exposure to elevated levels to Hg leads to headaches, insomnia, irritability, memory loss, and slow sensory and motor nerve function along with depressed cognition, renal failure, chest pain, dyspnea, and impaired lung activity.[72] Chronic exposures to elemental mercury lead to hypersalivation and erethism.[72] Several studies show the risk of spontaneous abortions and birth defects in infants on elemental mercury exposure.[72] Elemental mercury has a reference concentration of 0.0003 mg/m3, and when exposures are greater than this level, the possibility of harmful consequences to health increases.[72]

Workplace fatality and injury statistics

United States

The Occupational Safety and Health Statistics (OSHS) program in the Bureau of Labor Statistics of the United States Department of Labor compiles information about workplace fatalities and non-fatal injuries in the United States. The OSHS program produces three annual reports:

- Counts and rates of nonfatal occupational injuries and illnesses by detailed industry and case type (SOII summary data)

- Case circumstances and worker demographic data for nonfatal occupational injuries and illnesses resulting in days away from work (SOII case and demographic data)

- Counts and rates of fatal occupational injuries (CFOI data)[73]

In 1970, an estimated 14,000 workers were killed on the job – by 2010, the workforce had doubled, but workplace deaths were down to about 4,500.[74] Between 1913 and 2013, workplace fatalities dropped by approximately 80%.[75]

The Bureau also compiles information about the most dangerous jobs. According to the census of occupational injuries 4,679 people died on the job in 2014.[76] In 2015, a decline in nonfatal workplace injuries and illnesses was observed, with private industry employers reporting approximately 2.9 million incidents, nearly 48,000 fewer cases than in 2014.[77] The Bureau also uses tools like www.AgInjuryNews.org[78] to identify and compile additional sources of fatality reports for their datasets.[79][80]

| 2017 Number and rate of fatal work injuries by major occupation group[81] | ||

|---|---|---|

| Occupation Group | Fatalities | Fatalities per 100,000 employees |

| Transportation and material moving | 1,443 | 15.9 |

| Construction and extraction | 965 | 12.2 |

| Service | 778 | 3.3 |

| Management, business, and financial operations | 425 | 1.6 |

| Installation, maintenance, and repair | 414 | 8.1 |

| Farming, fishing, and forestry | 264 | 20.9 |

| Sales and related | 232 | 1.6 |

| Professional and related | 229 | 0.7 |

| Production | 221 | 2.6 |

| Office and administrative support | 101 | 0.6 |

| All occupations | 5,147 | 3.5 |

A total of 5,147 workers died from a work-related injury in the U.S. in 2017, down slightly from the 2016 total of 5,190. The fatal injury rate was 3.5 per 100,000 full-time equivalent workers, also down from 3.6 in 2016.[82]

| 2017 employer-reported injuries and illnesses[83][84][85] | ||

|---|---|---|

| Industry | Rate per 100 full-time employees | Number |

| Agriculture, forestry, fishing and hunting | 5.0 | 50,200 |

| Mining, quarrying, and oil and gas extraction | 1.5 | 10,200 |

| Construction | 3.1 | 198,100 |

| Manufacturing | 3.5 | 428,900 |

| Wholesale trade | 2.8 | 157,900 |

| Retail trade | 3.3 | 395,700 |

| Transportation and warehousing | 4.6 | 215,700 |

| Utilities | 2.0 | 11,200 |

| Information | 1.3 | 33,700 |

| Finance and insurance | 0.5 | 27,500 |

| Real estate, rental, and leasing | 2.4 | 46,600 |

| Professional, scientific, and technical services | 0.8 | 69,600 |

| Management of companies and enterprises | 0.9 | 20,600 |

| Administrative and waste services | 2.2 | 116,900 |

| Educational services (private) | 1.9 | 38,500 |

| Health care and social assistance (private) | 4.1 | 582,800 |

| Arts, entertainment, and recreation | 4.2 | 58,900 |

| Accommodation and food services | 3.2 | 282,600 |

| Other services (except public administration) | 2.1 | 66,000 |

| State government: Nursing and residential care facilities | 10.9 | 12,100 |

| State government: Correctional institutions | 7.9 | 31,800 |

| State government: Hospitals | 7.7 | 24,200 |

| State government: Police Protection | 7.2 | 8,000 |

| State government: Colleges, Universities, and Professional Schools | 1.8 | 22,000 |

| Local government: Public administration | 6.5 | 225,800 |

| Local government: Nursing and residential care facilities | 6.0 | 3,200 |

| Local government: Water sewage and other systems | 5.4 | 8,200 |

| Local government: Hospitals | 5.1 | 27,100 |

| Local government: Elementary and secondary schools | 3.9 | 198,900 |

| All industries including state and local government | 3.8 | 3,372,900 |

About 2.8 million nonfatal workplace injuries and illnesses were reported by private industry employers in 2017, occurring at a rate of 2.8 cases per 100 full-time workers. Both the number of injuries and illnesses and the rate of these cases declined from 2016.[86]

| Nonfatal occupational injuries and illnesses by nature, 2017[87] | |

|---|---|

| Cause of injury and illness | 2017 rate per 10,000 full-time employees[88] |

| Contact with objects or equipment | 23.2 |

| Falls, slips, trips | 23.1 |

| Over-exertion and bodily reaction | 30.0 |

| Violence and other injuries by person or animal | 4.0 |

| Transportation incidents | 4.9 |

| Exposure to harmful substances or environments | 3.8 |

| Fires and explosions | 0.1 |

| Total | 89.4 |

European Union

In most countries males comprise the vast majority of workplace fatalities. In the EU as a whole, 94% of death were of males.[89] In the UK the disparity was even greater with males comprising 97.4% of workplace deaths. In the UK there were 171 fatal injuries at work in financial year 2011–2012, compared with 651 in calendar year 1974; the fatal injury rate declined over that period from 2.9 fatalities per 100,000 workers to 0.6 per 100,000 workers.[90] Of course the period saw the virtual disappearance from the UK of some historically risky industries (deep sea fishing, coal mining).

Russian Federation

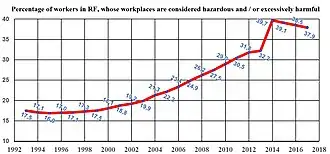

One of the decisions taken by Communists during the reign of Stalin was the reduction in the number of accidents and occupational diseases to zero.[91] The tendency to decline remained in the RF in the early 21st century, and the same methods of falsification are used, so that the real occupational morbidity and the number of accidents are unknown.[92]

After the destruction of the USSR, the enterprises became owned by new owners who were not interested in preserving the life and health of workers. They did not spend money on equipment modernization, and the share of harmful workplaces increased.[93] The state did not interfere in this, and sometimes it helped employers. At first, the process of growth was slow, due to the fact that in the 1990s this was compensated by mass de-industrialization (factories with foundries and other harmful types of production were closed). In the 2000s, this method of restraining the growth of the share of harmful workplaces was exhausted. Therefore, in the 2010s the Ministry of Labor adopted the Federal law 426-FZ, which equated the issuance of personal protective equipment to the employee to real improvement of working conditions; and the Ministry of Health made significant changes in the methods of risk assessment in the workplace.[94] This explains the "decline" in the proportion of workers working in harmful conditions after 2014 – it happened not in practice, but only on paper.

Specialists from the Izmerov Research Institute of Occupational Health (the oldest in the world) analyzed information about the health status of workers and the assessment of their working conditions using the new methods of risk assessment. Their findings show that new "methods" do not provide a real picture of working conditions. This is most clearly shown by the results obtained at enterprises producing aluminum. For example, the share of jobs with very harmful working conditions ("labor class" (health hazard class) = 3.4) decreased by an order of magnitude (from 11.6% to 1.2%). But the reduction of the level of harmful factors at these enterprises did not happen at all; and the proportion of workers with chronic intoxication with fluorine compounds was 38.7%.[95]

| Number of the workers, killed at the workplaces. | ||||

| Year | Russian Federal State Statistics Service | Social Insurance Fund of the Russian Federation | Federal service for labor and employment (Роструд) | Maximum discrepancy in the data |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2001 | 4368 | 5755 | 6194 | 1826 |

| 2002 | 3920 | 5715 | 5865 | 1945 |

| 2003 | 3536 | 5180 | 5185 | 1649 |

| 2004 | 3292 | 4684 | 4924 | 1632 |

| 2005 | 3091 | 4235 | 4604 | 1513 |

| 2006 | 2881 | 3591 | 4301 | 1420 |

| 2007 | 2966 | 3677 | 4417 | 1451 |

| 2008 | 2548 | 3238 | 3931 | 1383 |

| 2009 | 1967 | 2598 | 3200 | 1233 |

| 2010 | 2004 | 2438 | 3120 | 1116 |

| According to prof. Oleg Rusak, three state bodies cannot count the number of people killed in accidents at workplaces. According to Rostrud, it was revealed 2074 hidden accidents at work. Employers were hidden 64 group accidents and 404 deaths, 1332 severe accidents (2008).

Source[R 1] | ||||

In the opinion of the state inspector, the use of punishment against the guilty manager (disqualification, ban on executive work) is too rare: "The practice of court decisions shows that disqualification of the leader is possible, but for this he or she must kill 5–7 employees, or more".[96] Responsibility for wrong decisions is absent or very low; and punishment of guilty executives in the construction industry usually does not occur.[97]

Management systems

National

National management system standards for occupational health and safety include AS/NZS 4801-2001 for Australia and New Zealand, CAN/CSA-Z1000-14 for Canada and ANSI/ASSE Z10-2012 for the United States.[98][99] Association Française de Normalisation (AFNOR) in France also developed occupational safety and health management standards.[100] In the United Kingdom, non-departmental public body Health and Safety Executive published Managing for health and safety (MFHS), an online guidance.[101] In Germany, the state factory inspectorates of Bavaria and Saxony had introduced the management system OHRIS. In the Netherlands, the management system Safety Certificate Contractors combines management of occupational health and safety and the environment.

International

ISO 45001 was published in March 2018 and implemented in March 2021.

Previously, the International Labour Organization (ILO) published ILO-OSH 2001, also titled "Guidelines on occupational safety and health management systems" to assist organizations with introducing OSH management systems.[102] These guidelines encourage continual improvement in employee health and safety, achieved via a constant process of policy, organization, planning & implementation, evaluation, and action for improvement, all supported by constant auditing to determine the success of OSH actions.[102] From 1999 to 2018, the occupational health and safety management system standard OHSAS 18001 was adopted as a British and Polish standard and widely used internationally. OHSAS 18000 comprised two parts, OHSAS 18001 and 18002 and was developed by a selection of leading trade bodies, international standards and certification bodies to address a gap where no third-party certifiable international standard existed. It was intended to integrate with ISO 9001 and ISO 14001.[103]

Since March 2021, ISO 45001 has replaced OHSAS 18001 and now acts as a base for workplace health and safety.

National legislation and public organizations

Occupational safety and health practice vary among nations with different approaches to legislation, regulation, enforcement, and incentives for compliance. In the EU, for example, some member states promote OSH by providing public monies as subsidies, grants or financing, while others have created tax system incentives for OSH investments. A third group of EU member states has experimented with using workplace accident insurance premium discounts for companies or organisations with strong OSH records.[104][105]

Australia

In Australia, the Commonwealth, four of the six states and both territories have enacted and administer harmonised Work Health and Safety Legislation in accordance with the Intergovernmental Agreement for Regulatory and Operational Reform in Occupational Health and Safety.[106] Each of these jurisdictions has enacted Work Health & Safety legislation and regulations based on the Commonwealth Work Health and Safety Act 2011 and common Codes of Practice developed by Safe Work Australia.[107] Some jurisdictions have also included mine safety under the model approach, however, most have retained separate legislation for the time being. In August 2019 Western Australia committed to join nearly every other State and Territory in implementing the harmonised Model WHS Act, Regulations and other subsidiary legislation.[108] Victoria has retained its own regime, although the Model WHS laws themselves drew heavily on the Victoria approach.

Canada

In Canada, workers are covered by provincial or federal labour codes depending on the sector in which they work. Workers covered by federal legislation (including those in mining, transportation, and federal employment) are covered by the Canada Labour Code; all other workers are covered by the health and safety legislation of the province in which they work. The Canadian Centre for Occupational Health and Safety (CCOHS), an agency of the Government of Canada, was created in 1978 by an Act of Parliament. The act was based on the belief that all Canadians had "a fundamental right to a healthy and safe working environment." CCOHS is mandated to promote safe and healthy workplaces to help prevent work-related injuries and illnesses. The CCOHS maintains a useful (partial) list of OSH regulations for Canada and its provinces.[109]

European Union

| Number of full-time OSH inspectors | |

|---|---|

| Italy | 17.7 |

| Finland | 17.5 |

| Denmark | 11.9 |

| United Kingdom | 11.1 |

| Norway | 10.6 |

| Sweden | 10 |

| Belgium | 5.3 |

| Netherlands | 4.8 |

| Ireland | 4.5 |

| Greece | 4.1 |

| France | 3.5 |

| Spain | 2.1 |

In the European Union, member states have enforcing authorities to ensure that the basic legal requirements relating to occupational health and safety are met. In many EU countries, there is strong cooperation between employer and worker organisations (e.g. unions) to ensure good OSH performance as it is recognized this has benefits for both the worker (through maintenance of health) and the enterprise (through improved productivity and quality). In 1994, the European Agency for Safety and Health at Work was founded.

Member states of the European Union have all transposed into their national legislation a series of directives that establish minimum standards on occupational health and safety. These directives (of which there are about 20 on a variety of topics) follow a similar structure requiring the employer to assess the workplace risks and put in place preventive measures based on a hierarchy of control. This hierarchy starts with elimination of the hazard and ends with personal protective equipment.

However, certain EU member states admit to having lacking quality control in occupational safety services, to situations in which risk analysis takes place without any on-site workplace visits and to insufficient implementation of certain EU OSH directives. Based on this, it is hardly surprising that the total societal costs of work-related health problems and accidents vary from 2.6% to 3.8% of GNP between the EU member states.[112]

Denmark

In Denmark, occupational safety and health is regulated by the Danish Act on Working Environment and cooperation at the workplace.[113] The Danish Working Environment Authority (Arbejdstilsynet) carries out inspections of companies, draws up more detailed rules on health and safety at work and provides information on health and safety at work.[114] The result of each inspection is made public on the web pages of the Danish Working Environment Authority so that the general public, current and prospective employees, customers and other stakeholders can inform themselves about whether a given organization has passed the inspection.[115]

Netherlands

In the Netherlands the laws for safety and health at work are registered in the Working Conditions Act (Arbeidsomstandighedenwet and Arbeidsomstandighedenbeleid). Apart from the direct laws directed to safety and health in working environments, the private domain has added health and safety rules in Working Conditions Policies (Arbeidsomstandighedenbeleid), which are specified per industry. The Ministry of Social Affairs and Labour (SZW) monitors adherence to the rules through their inspection service. This inspection service investigates industrial accidents and the service can suspend work when the Working Conditions Act has been violated and impose fines. Companies can raise their security levels by certifying the company with a VCA-certificate (Safety, Health and Environment). All employees have to obtain a VCA-certificate too, with which they can prove that they know how to work according to the current and applicable safety and environmental regulations. Besides the VCA-certification, companies and organisations are able to acquire certifications on ISO guidelines. The International Organization for Standardization publish guidelines for safety and health in working environments, mostly focused on a particular part, such as Risk Management (ISO31000) or Occupational Health and Safety (ISO45001).[116] By acquiring certifications to these guidelines, companies and organisations will often comply to demands from the government or insurance agencies.

Ireland

The main health and safety law in Ireland is the Safety, Health and Welfare at Work Act 2005,[117] which replaced earlier 1989 legislation. The Health and Safety Authority, based in Dublin, is responsible for enforcing health and safety at work legislation.[117]

Spain

In Spain, occupational safety and health is regulated by the Spanish Act on Prevention of Labour Risks. The Ministry of Labour is the authority responsible for issues relating to labour environment.[118] The National Institute for Labour Safety and Hygiene is the technical public Organization specialized in occupational safety and health.[119]

Sweden

In Sweden, occupational safety and health is regulated by the Work Environment Act. The Swedish Work Environment Authority is the government agency responsible for issues relating to the working environment. The agency should work to disseminate information and furnish advice on OSH, has a mandate to carry out inspections, and a right to issue stipulations and injunctions to any non-compliant employer.[120]

India

In India, the Labour Ministry formulates national policies on occupational safety and health in factories and docks with advice and assistance from Directorate General of Factory Advice Service and Labour Institutes (DGFASLI), and enforces its Policies through inspectorates of factories and inspectorates of dock safety.[121] DGFASLI is the technical arm of the Ministry of Labour & Employment, Government of India and advises the factories on various problems concerning safety, health, efficiency and well-being of the persons at work places.[121] The DGFASLI provides technical support in formulating rules, conducting occupational safety surveys and also for conducting occupational safety training programs.[122]

Indonesia

In Indonesia, the Ministry of Manpower is responsible to ensure the safety, health and welfare of workers while working, in a factory, or even the area surrounding the factory where labourers work. There are a few rules that control the safety of workers, for example Occupational Safety Act 1970 or Occupational Health Act 1992.[123] The sanctions, however, are still low and the violations of these laws are still at a high rate – with a maximum of 15 million rupiahs fine and/or a maximum of one year in prison.[124]

Malaysia

In Malaysia, the Department of Occupational Safety and Health (DOSH) under the Ministry of Human Resource is responsible to ensure that the safety, health and welfare of workers in both the public and private sector is upheld. DOSH is responsible to enforce the Factories and Machinery Act 1967 and the Occupational Safety and Health Act 1994. Malaysia has a statutory mechanism for worker involvement through elected health and safety representatives and health and safety committees. This followed a similar approach originally adopted in Scandinavia.

People's Republic of China

In the People's Republic of China, the Ministry of Health is responsible for occupational disease prevention and the State Administration of Work Safety for safety issues at work. On the provincial and municipal level, there are Health Supervisions for occupational health and local bureaus of Work Safety for safety. The "Occupational Disease Control Act of PRC" came into force on May 1, 2002.[125] and Work safety Act of PRC on November 1, 2002.[126] The Occupational Disease Control Act is under revision. The prevention of occupational disease is still in its initial stage compared with industrialised countries such as the US or UK.

Singapore

In Singapore, the Ministry of Manpower operates various checks and campaigns against unsafe work practices, such as when working at height, operating cranes and in traffic management. Examples include Operation Cormorant and the Falls Prevention Campaign.[127]

South Africa

In South Africa the Department of Employment and Labour is responsible for occupational health and safety inspection and enforcement in commerce and industry apart from mining and energy production, where the Department of Mineral Resources is responsible.

The main statutory legislation on Health and Safety in the jurisdiction of the Department of Labour is Act No. 85 of 1993: Occupational Health and Safety Act as amended by Occupational Health and Safety Amendment Act, No. 181 Of 1993.

Regulations to the OHS Act include:

- General Administrative Regulations, 2003[128]

- Certificate of Competency Regulations, 1990[129]

- Construction Regulations, 2014

- Diving Regulations 2009[130]

- Driven Machinery Regulations, 1988[131]

- Environmental Regulations for Workplaces, 1987[132]

- General Machinery regulations, 1988[133]

- General Safety Regulations, 1986[134]

- Noise induced hearing loss regulations, 2003[135]

- Pressure Equipment Regulations, 2004

Syria

In Syria, health and safety is the responsibility of the Ministry of Social Affairs and Labour.[136]

Taiwan

In Taiwan, the Occupational Safety and Health Administration of the Ministry of Labor is in charge of occupational safety and health.[137] The matter is governed under the Occupational Safety and Health Act.[138]

In 2007, the Taiwan Occupational Safety and Health Management System (TOSHMS), which defined the basic regulations about occupational safety standard, was released.[139]

United Arab Emirates

OSHAD was introduced in February 2010 to regulate the implementation of occupational health and safety in the emirates of Abu Dhabi.[140]

United Kingdom

Health and safety legislation in the UK is drawn up and enforced by the Health and Safety Executive and local authorities (the local council) under the Health and Safety at Work etc. Act 1974[141][142] (HASAWA). HASAWA introduced (section 2) a general duty on an employer to ensure, so far as is reasonably practicable, the health, safety and welfare at work of all his employees; with the intention of giving a legal framework supporting 'codes of practice' not in themselves having legal force but establishing a strong presumption as to what was reasonably practicable (deviations from them could be justified by appropriate risk assessment). The previous reliance on detailed prescriptive rule-setting was seen as having failed to respond rapidly enough to technological change, leaving new technologies potentially un-regulated or inappropriately regulated.[143][144] HSE has continued to make some regulations giving absolute duties (where something must be done with no 'reasonable practicability' test) but in the UK the regulatory trend is away from prescriptive rules, and towards 'goal setting' and risk assessment. Recent major changes to the laws governing asbestos and fire safety management embrace the concept of risk assessment. The other key aspect of the UK legislation is a statutory mechanism for worker involvement through elected health and safety representatives and health and safety committees. This followed a similar approach in Scandinavia, and that approach has since been adopted in countries such as Australia, Canada, New Zealand and Malaysia.

For the UK, the government organisation dealing with occupational health has been the Employment Medical Advisory Service but in 2014 a new occupational health organisation – the Health and Work Service – was created to provide advice and assistance to employers in order to get back to work employees on long-term sick-leave.[145] The service, funded by government, will offer medical assessments and treatment plans, on a voluntary basis, to people on long-term absence from their employer; in return, the government will no longer foot the bill for Statutory Sick Pay provided by the employer to the individual.

United States

In the United States, President Richard Nixon signed the Occupational Safety and Health Act into law on December 29, 1970. The act created the three agencies which administer OSH: the Occupational Safety and Health Administration, National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health, and the Occupational Safety and Health Review Commission.[146] The act authorized the Occupational Safety and Health Administration OSHA to regulate private employers in the 50 states, the District of Columbia, and territories.[147] The Act establishing it includes a general duty clause (29 U.S.C. § 654, 5(a)) requiring an employer to comply with the Act and regulations derived from it, and to provide employees with "employment and a place of employment which are free from recognized hazards that are causing or are likely to cause [them] death or serious physical harm".

OSHA was established in 1971 under the Department of Labor. It has headquarters in Washington, DC, and ten regional offices, further broken down into districts, each organized into three sections; compliance, training, and assistance. Its stated mission is "to assure safe and healthful working conditions for working men and women by setting and enforcing standards and by providing training, outreach, education and assistance."[148] The original plan was for OSHA to oversee 50 state plans with OSHA funding 50% of each plan, although it has not worked out that way: there are currently 26 approved state plans (4 cover only public employees),[74] and no other states want to participate. OSHA manages the plan in the states not participating.[74]

OSHA develops safety standards in the Code of Federal Regulations and enforces those safety standards through compliance inspections conducted by Compliance Officers; enforcement resources are focussed on high-hazard industries. Worksites may apply to enter OSHA's Voluntary Protection Program (VPP); a successful application leads to an on-site inspection; if this is passed the site gains VPP status and OSHA no longer inspect it annually nor (normally) visit it unless there is a fatal accident or an employee complaint until VPP revalidation (after 3–5 years).[74] VPP sites generally have injury and illness rates less than half the average for their industry.

It has 73 specialists in local offices to provide tailored information and training to employers and employees at little or no cost.[5] Similarly OSHA produces a range of publications, provides advice to employers and funds consultation services available for small businesses.

OSHA's Alliance Program enables groups committed to worker safety and health to work with it to develop compliance assistance tools and resources, share information with workers and employers, and educate them about their rights and responsibilities. OSHA also has a Strategic Partnership Program that zeros in on specific hazards or specific geographic areas.[74] OSHA manages Susan B. Harwood grants to non-profit organisations to train workers and employers to recognize, avoid, and prevent safety and health hazards in the workplace. Grants focus on small business, hard-to-reach workers and high-hazard industries.

The National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health, created under the same act, works closely with OSHA and provides the research behind many of OSHA's regulations and standards.[149]

Professional roles and responsibilities

The roles and responsibilities of OSH professionals vary regionally but may include evaluating working environments, developing, endorsing and encouraging measures that might prevent injuries and illnesses, providing OSH information to employers, employees, and the public, providing medical examinations, and assessing the success of worker health programs.

Europe

In Norway, the main required tasks of an occupational health and safety practitioner include the following:

- Systematic evaluations of the working environment

- Endorsing preventive measures which eliminate causes of illnesses in the workplace

- Providing information on the subject of employees' health

- Providing information on occupational hygiene, ergonomics, and environmental and safety risks in the workplace[150]

In the Netherlands, the required tasks for health and safety staff are only summarily defined and include the following:

- Providing voluntary medical examinations

- Providing a consulting room on the work environment to the workers

- Providing health assessments (if needed for the job concerned).[151]

"The main influence of the Dutch law on the job of the safety professional is through the requirement on each employer to use the services of a certified working conditions service to advise them on health and safety".[151] A "certified service" must employ sufficient numbers of four types of certified experts to cover the risks in the organisations which use the service:

- A safety professional

- An occupational hygienist

- An occupational physician

- A work and organisation specialist.[151]

In 2004, 37% of health and safety practitioners in Norway and 14% in the Netherlands had an MSc; 44% had a BSc in Norway and 63% in the Netherlands; and 19% had training as an OSH technician in Norway and 23% in the Netherlands.[151]

United States

The main tasks undertaken by the OHS practitioner in the US include:

- Develop processes, procedures, criteria, requirements, and methods to attain the best possible management of the hazards and exposures that can cause injury to people, and damage property, or the environment;

- Apply good business practices and economic principles for efficient use of resources to add to the importance of the safety processes;

- Promote other members of the company to contribute by exchanging ideas and other different approaches to make sure that every one in the corporation possess OHS knowledge and have functional roles in the development and execution of safety procedures;

- Assess services, outcomes, methods, equipment, workstations, and procedures by using qualitative and quantitative methods to recognise the hazards and measure the related risks;

- Examine all possibilities, effectiveness, reliability, and expenditure to attain the best results for the company concerned.[152]

Knowledge required by the OHS professional in the US include:

- Constitutional and case law controlling safety, health, and the environment

- Operational procedures to plan/develop safe work practices

- Safety, health and environmental sciences

- Design of hazard control systems (i.e. fall protection, scaffoldings)

- Design of recordkeeping systems that take collection into account, as well as storage, interpretation, and dissemination

- Mathematics and statistics

- Processes and systems for attaining safety through design.[153]

Some skills required by the OHS professional in the US include (but are not limited to):

- Understanding and relating to systems, policies and rules

- Holding checks and having control methods for possible hazardous exposures

- Mathematical and statistical analysis

- Examining manufacturing hazards

- Planning safe work practices for systems, facilities, and equipment

- Understanding and using safety, health, and environmental science information for the improvement of procedures

- Interpersonal communication skills.[153]

Differences between countries and regions

Because different countries take different approaches to ensuring occupational safety and health, areas of OSH need and focus also vary between countries and regions. Similar to the findings of the ENHSPO survey conducted in Australia, the Institute of Occupational Medicine in the UK found that there is a need to put greater emphasis on work-related illness in the UK.[154] In contrast, in Australia and the US, a major responsibility of the OHS professional is to keep company directors and managers aware of the issues that they face in regards to occupational health and safety principles and legislation. However, in some other areas of Europe, it is precisely this which has been lacking: "Nearly half of senior managers and company directors do not have an up-to-date understanding of their health and safety-related duties and responsibilities."[155]

Identifying safety and health hazards

Hazards, risks, outcomes

The terminology used in OSH varies between countries, but generally speaking:

- A hazard is something that can cause harm if not controlled.

- The outcome is the harm that results from an uncontrolled hazard.

- A risk is a combination of the probability that a particular outcome will occur and the severity of the harm involved.[156]

"Hazard", "risk", and "outcome" are used in other fields to describe e.g. environmental damage, or damage to equipment. However, in the context of OSH, "harm" generally describes the direct or indirect degradation, temporary or permanent, of the physical, mental, or social well-being of workers. For example, repetitively carrying out manual handling of heavy objects is a hazard. The outcome could be a musculoskeletal disorder (MSD) or an acute back or joint injury. The risk can be expressed numerically (e.g. a 0.5 or 50/50 chance of the outcome occurring during a year), in relative terms (e.g. "high/medium/low"), or with a multi-dimensional classification scheme (e.g. situation-specific risks).

Hazard identification

Hazard identification or assessment is an important step in the overall risk assessment and risk management process. It is where individual work hazards are identified, assessed and controlled/eliminated as close to source (location of the hazard) as reasonably as possible. As technology, resources, social expectation or regulatory requirements change, hazard analysis focuses controls more closely toward the source of the hazard. Thus hazard control is a dynamic program of prevention. Hazard based programs also have the advantage of not assigning or implying there are "acceptable risks" in the workplace.[157] A hazard-based program may not be able to eliminate all risks, but neither does it accept "satisfactory" – but still risky – outcomes. And as those who calculate and manage the risk are usually managers while those exposed to the risks are a different group, workers, a hazard-based approach can by-pass conflict inherent in a risk-based approach.

The information that needs to be gathered from sources should apply to the specific type of work from which the hazards can come from. As mentioned previously, examples of these sources include interviews with people who have worked in the field of the hazard, history and analysis of past incidents, and official reports of work and the hazards encountered. Of these, the personnel interviews may be the most critical in identifying undocumented practices, events, releases, hazards and other relevant information. Once the information is gathered from a collection of sources, it is recommended for these to be digitally archived (to allow for quick searching) and to have a physical set of the same information in order for it to be more accessible. One innovative way to display the complex historical hazard information is with a historical hazards identification map, which distills the hazard information into an easy to use graphical format. In the construction industry specifically, job hazard analysis (JHA) software allows safety managers and crew members to identify potential hazards at the job site and improve accident prevention.[158]

Risk assessment

Modern occupational safety and health legislation usually demands that a risk assessment be carried out prior to making an intervention. It should be kept in mind that risk management requires risk to be managed to a level which is as low as is reasonably practical.[159]

This assessment should:

- Identify the hazards

- Identify all affected by the hazard and how

- Evaluate the risk

- Identify and prioritize appropriate control measures.

The calculation of risk is based on the likelihood or probability of the harm being realized and the severity of the consequences. This can be expressed mathematically as a quantitative assessment (by assigning low, medium and high likelihood and severity with integers and multiplying them to obtain a risk factor), or qualitatively as a description of the circumstances by which the harm could arise.

The assessment should be recorded and reviewed periodically and whenever there is a significant change to work practices. The assessment should include practical recommendations to control the risk. Once recommended controls are implemented, the risk should be re-calculated to determine if it has been lowered to an acceptable level. Generally speaking, newly introduced controls should lower risk by one level, i.e., from high to medium or from medium to low.[160]

Contemporary developments

On an international scale, the World Health Organization (WHO) and the International Labour Organization (ILO) have begun focusing on labour environments in developing nations with projects such as Healthy Cities.[161] Many of these developing countries are stuck in a situation in which their relative lack of resources to invest in OSH leads to increased costs due to work-related illnesses and accidents. The European Agency for Safety and Health at Work states indicates that nations having less developed OSH systems spend a higher fraction of their gross national product on job-related injuries and illness[162] – taking resources away from more productive activities. The ILO estimates that work-related illness and accidents cost up to 10% of GDP in Latin America, compared with just 2.6% to 3.8% in the EU.[163] There is continued use of asbestos, a notorious hazard, in some developing countries. So asbestos-related disease is expected to continue to be a significant problem well into the future.

Nanotechnology

Nanotechnology is an example of a new, relatively unstudied technology. A Swiss survey of 138 companies using or producing nanoparticulate matter in 2006 resulted in forty completed questionnaires. Sixty-five per cent of respondent companies stated they did not have a formal risk assessment process for dealing with nanoparticulate matter.[164] Nanotechnology already presents new issues for OSH professionals that will only become more difficult as nanostructures become more complex. The size of the particles renders most containment and personal protective equipment ineffective. The toxicology values for macro sized industrial substances are rendered inaccurate due to the unique nature of nanoparticulate matter. As nanoparticulate matter decreases in size its relative surface area increases dramatically, increasing any catalytic effect or chemical reactivity substantially versus the known value for the macro substance. This presents a new set of challenges in the near future to rethink contemporary measures to safeguard the health and welfare of employees against a nanoparticulate substance that most conventional controls have not been designed to manage.[165]

Coronavirus

Many countries' health and safety at work arrangements are currently focused on protection against the spread of COVID-19.[166][167] Both broad and industry-specific workplace hazard controls for COVID-19 have been proposed to minimize risks of disease transmission in the workplace.

The National Institute of Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH) National Occupational Research Agenda Manufacturing Council established an externally-lead COVID-19 workgroup to provide exposure control information specific to working in manufacturing environments. The workgroup identified disseminating information most relevant to manufacturing workplaces as a priority, and that would include providing content in Wikipedia. This includes evidence-based practices for infection control plans,[168] and communication tools.

Occupational health disparities

Occupational health disparities refer to differences in occupational injuries and illnesses that are closely linked with demographic, social, cultural, economic, and/or political factors.[169]

Education

There are multiple levels of training applicable to the field of occupational safety and health (OSH). Programs range from individual non-credit certificates and awareness courses focusing on specific areas of concern, to full doctoral programs. The University of Southern California was one of the first schools in the US to offer a Ph.D. program focusing on the field. Further, multiple master's degree programs exist, such as that of the Indiana State University who offer a Master of Science (MSc) and a Master of Arts (MA) in OSH. Other masters-level qualifications include the Master of Science (MSc) and Master of Research (MRes) degrees offered by the University of Hull in collaboration with the National Examination Board in Occupational Safety and Health (NEBOSH). Graduate programs are designed to train educators, as well as, high-level practitioners.

Many OSH generalists focus on undergraduate studies; programs within schools, such as that of the University of North Carolina's online Bachelor of Science in Environmental Health and Safety, fill a large majority of hygienist needs. However, smaller companies often do not have full-time safety specialists on staff, thus, they appoint a current employee to the responsibility. Individuals finding themselves in positions such as these, or for those enhancing marketability in the job-search and promotion arena, may seek out a credit certificate program. For example, the University of Connecticut's online OSH Certificate[170] provides students familiarity with overarching concepts through a 15-credit (5-course) program. Programs such as these are often adequate tools in building a strong educational platform for new safety managers with a minimal outlay of time and money. Further, most hygienists seek certification by organizations that train in specific areas of concentration, focusing on isolated workplace hazards. The American Society for Safety Engineers (ASSE), American Society for Safety Professionals (ASSP), American Board of Industrial Hygiene (ABIH), and American Industrial Hygiene Association (AIHA) offer individual certificates on many different subjects from forklift operation to waste disposal and are the chief facilitators of continuing education in the OSH sector.

In the US the training of safety professionals is supported by National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health through their NIOSH Education and Research Centers.

In the UK, both the National Examination Board in Occupational Safety and Health (NEBOSH) and the Institution of Occupational Safety and Health (IOSH) develop health and safety qualifications and courses which cater to a mixture of industries and levels of study. Although both organisations are based in the UK, their qualifications are recognised and studied internationally as they are delivered through their own global networks of approved providers.

In Australia, training in OSH is available at the vocational education and training level, and at university undergraduate and postgraduate level. Such university courses may be accredited by an Accreditation Board of the Safety Institute of Australia. The institute has produced a Body of Knowledge which it considers is required by a generalist safety and health professional, and offers a professional qualification based on a four-step assessment.[171]

One form of training delivered in the workplace is known as a "toolbox talk". According to the UK's Health and Safety Executive, a toolbox talk is a short presentation to the workforce on a single aspect of health and safety.[172] Such talks are often used, especially in the construction industry, by site supervisors, front line managers and owners of small construction firms to prepare and deliver advice on matters of health, safety and the environment and to obtain feedback from the workforce.[173] There is specific software used in construction for toolbox talks that allows safety managers to record safety meetings and track attendee signatures.[174]The Health and Safety Executive has also developed health and safety qualifications in collaboration with the NEBOSH.

World Day for Safety and Health at Work

On April 28 The International Labour Organization celebrates "World Day for Safety and Health"[175] to raise awareness of safety in the workplace. Occurring annually since 2003,[176] each year it focuses on a specific area and bases a campaign around the theme.[177]

See also

Related topics

- Decent work

- Examinetics - mobile occupational health screening

- Mental health day

- National Occupational Research Agenda

- Occupational disease – Any chronic disorder that occurs as a result of work or occupational activity

- Occupational epidemiology

- Occupational health psychology – Health and Safety psychology

- Occupational Health Science (Journal)

- Occupational Medicine

- Occupational stress – Tensions related to work

- Prevention through design – Reduction of occupational hazards by early planning in the design process

- Principles of motion economy

- Product stewardship

- Public security

- Safety Jackpot

- Seoul Declaration on Safety and Health at Work

- Society for Occupational Health Psychology

- Work accident – Occurrence during work that leads to physical or mental harm

- Workers' compensation – Form of insurance

Laws

- Health and Safety at Work etc. Act 1974 (UK)

- Occupational Safety and Health Act (United States) – United States labor law

- Occupational Safety and Health Act 1994 (Malaysia)

- Timeline of major U.S. environmental and occupational health regulation

- Workplace Safety and Health Act – Statute of the Parliament of Singapore (Singapore)

Related fields

- Environmental health – Public health branch focused on environmental impacts on human health

- Environmental medicine

- Human factors and ergonomics – Designing systems to suit their users

- Industrial engineering – Branch of engineering which deals with the optimization of complex processes or systems

- Industrial and organizational psychology – Branch of psychology

- Labor rights – Legal rights and human rights relating to labor relations between workers and employers

- Occupational health psychology – Health and Safety psychology

- Occupational hygiene – Management of workplace health hazards

- Occupational medicine – Medical specialty concerned with the maintenance of health in the workplace

- Public health – Promoting health through organized efforts and informed choices of society and individuals

- Safety engineering – Engineering discipline which assures that engineered systems provide acceptable levels of safety

- Toxicology – Study of substances harmful to living organisms

Notes

- O. Rusak, A. Tsvetkova (2013). "Registration, investigation, and calculation of Accident" (PDF). Life Safety. Occupational Health & Safety; and public health (1): 6–12. ISSN 1684-6435. (On Russian)

References

- It can be confusing that British English also uses industrial medicine to refer to occupational health and safety and uses occupational health to refer to occupational medicine. See the Collins Dictionary entries for industrial medicine and occupational medicine and occupational health.

- "occupational health". TheFreeDictionary.com. Retrieved 5 March 2022.

- "Oak Ridge National Laboratory". Ornl.gov. Retrieved 2015-10-30.

- "safety at work". 20 March 2022. Retrieved 2022-03-21.

- Fanning, Fred E. (2003). Basic Safety Administration: A Handbook for the New Safety Specialist, Chicago: American Society of Safety Engineers

- "Safety and health at work". International Labour Organization. Retrieved 3 August 2021.

- "Guidance note: General duty of care in Western Australian workplaces 2005" (PDF). Government of Western Australia. Retrieved 15 July 2014.

- "Occupational health". Wpro.who.int. Archived from the original on April 26, 2014. Retrieved 2015-10-30.

- "WHO Definition of Health". World Health Organization. World Health Organization. Archived from the original on 2016-07-07.

- "Occupational Health Services And Practice". Ilo.org. Archived from the original on 2012-09-04. Retrieved 2013-02-15.

- Koryakov, Alexey Georgievich; Zhemerikin, Oleg Igorevich; Prazauskas, Martinas (2020). "Improving the Labor Safety and Operational Efficiency of the Company: Synergy Is Possible and Necessary". Proceedings of the 36th International Business Information Management Association (IBIMA). pp. 6371–6375. ISBN 978-0-9998551-5-7.

- Van Dijk, Frank; Caraballo-Arias, Yohama (2021). "Where to Find Evidence-Based Information on Occupational Safety and Health?". Annals of Global Health. 87 (1): 6. doi:10.5334/aogh.3131. PMC 7792450. PMID 33505865.

Text was copied from this source, which is available under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Text was copied from this source, which is available under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. - Hutchins, B L; Harrison, A (1911). A history of factory legislation by; Published 1911 (2nd ed.). Westminster: P S King & Son. Retrieved 30 June 2015.

- Edmonds, O. P.; Edmonds, E. L. (1963-07-01). "An Account of the Founding of H.M. Inspectorate of Mines and the Work of the First Inspector Hugh Seymour Tremenheere". British Journal of Industrial Medicine. 20 (3): 210–217. doi:10.1136/oem.20.3.210. ISSN 0007-1072. PMC 1039202. PMID 14046158.

- Abrams, Herbert K. (2001). "A Short History of Occupational Health" (PDF). Journal of Public Health Policy. 22 (1): 34–80. doi:10.2307/3343553. JSTOR 3343553. PMID 11382089. S2CID 13398392. Retrieved 9 August 2012.

- Concha-Barrientos, M., Imel, N.D., Driscoll, T., Steenland, N.K., Punnett, L., Fingerhut, M.A., Prüss-Üstün, A., Leigh, J., Tak, S.W., Corvalàn, C. (2004). Selected occupational risk factors. In M. Ezzati, A.D. Lopez, A. Rodgers & C.J.L. Murray (Eds.), Comparative Quantification of Health Risks. Geneva: World Health Organization.

- Ramos, Athena; Carlo, Gustavo; Grant, Kathleen; Bendixsen, Casper; Fuentes, Axel; Gamboa, Rodrigo; Ramos, Athena K.; Carlo, Gustavo; Grant, Kathleen M. (2018-09-02). "A Preliminary Analysis of Immigrant Cattle Feedyard Worker Perspectives on Job-Related Safety Training". Safety. 4 (3): 37. doi:10.3390/safety4030037.

- Pega, Frank; Nafradi, Balint; Momen, Natalie; Ujita, Yuka; Streicher, Kai; Prüss-Üstün, Annette; Technical Advisory Group (2021). "Global, regional, and national burdens of ischemic heart disease and stroke attributable to exposure to long working hours for 194 countries, 2000–2016: A systematic analysis from the WHO/ILO Joint Estimates of the Work-related Burden of Disease and Injury". Environment International. 154: 106595. doi:10.1016/j.envint.2021.106595. PMC 8204267. PMID 34011457.

- "Long working hours increasing deaths from heart disease and stroke: WHO, ILO". www.who.int. Retrieved 2022-06-21.

- "Noise and Hearing Loss Prevention". Workplace Safety & Health Topics. National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health. Retrieved 3 August 2012.

- "Fall Injuries Prevention in the Workplace". NIOSH Workplace Safety and Health Topic. National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health. Retrieved July 12, 2012.

- "Machine Safety". NIOSH Workplace Safety and Health Topics. National Institute of Occupational Safety and Health. Retrieved 11 July 2012.

- "CDC - Seasonal Influenza (Flu) in the Workplace - Guidance - NIOSH Workplace Safety and Health Topic". Cdc.gov. Retrieved 2015-09-03.

- "CDC - Insects and Scorpions - NIOSH Workplace Safety and Health Topic". Cdc.gov. Retrieved 2015-09-03.

- "CDC - Venomous Snakes - NIOSH Workplace Safety and Health Topic". Cdc.gov. Retrieved 2015-09-03.

- "CDC - Venomous Spiders - NIOSH Workplace Safety and Health Topic". Cdc.gov. Retrieved 2015-09-03.

- "CDC - Poisonous Plants - NIOSH Workplace Safety and Health Topic". Cdc.gov. Retrieved 2015-09-03.

- "CDC - Lyme Disease - NIOSH Workplace Safety and Health Topic". Cdc.gov. Retrieved 2015-09-03.

- "CDC - West Nile Virus - NIOSH Workplace Safety and Health Topic". Cc.gov. Retrieved 2015-09-03.