Sarcófago de Eshmunazar II

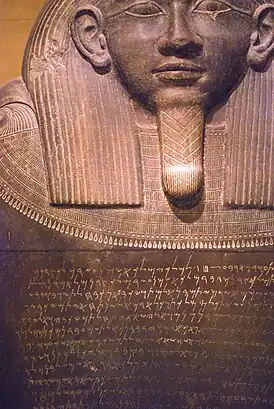

El sarcófago de Eshmunazar II es el sarcófago del rey de Sidón Eshmunazar II famoso por la inscripción sobre este rey fenicio. Fue manufacturado en Egipto a principios del siglo V a. C., desenterrado en 1855 en un yacimiento cercano a Sidón y depositado en el Museo del Louvre. Contiene una inscripción en idioma fenicio de gran importancia: fue la primera en lengua fenicia que se descubría en el área conocida como Fenicia, y además era la inscripción de este tipo más detallada jamás encontrada hasta ese momento.[1] [2]

| Sarcófago de Eshmunazar II | ||

|---|---|---|

.jpg.webp) | ||

| Material | anfibolita | |

| Tamaño | 2,56 x 1,25 m | |

| Escritura | alfabeto fenicio | |

| Descubrimiento | 1855 | |

Eshmunazar II (fenicio: 𐤀𐤔𐤌𐤍𐤏𐤆𐤓 ʾšmnʿzr, un nombre teofórico que significa 'Eshmun ayuda' o 'ayudante de Eshmun', similar a Eleazar) fue Rey de Sidón e hijo del rey Tabnit (posiblemente "Tenes" en griego). El sarcófago parece que fue hecho en Egipto, tallado en anfibolita de Wadi Hammamat. La inscripción dice que el "Señor de los reyes" concedió a los reyes sidonios "Dor y Jope, las poderosas tierras de Dagón, que se encuentran en la llanura de Sarón".[3]

Más de una docena de académicos de Europa y Estados Unidos se apresuraron a traducirlo e interpretar sus detalles en los dos años posteriores a la publicación de su descubrimiento.[4] Jean-Joseph-Léandre Bargès escribió que el idioma de la inscripción es "idéntico al hebreo, excepto por las inflexiones finales de algunas palabras y ciertas expresiones, en números muy reducidos, que no se encuentran en los textos bíblicos que han llegado a nosotros; el hecho de que el hebreo se escribiera y hablara en Sidón, en un momento en que los judíos que regresaban del cautiverio ya no escuchaban este idioma, es una prueba de que se conservó entre los fenicios más tiempo que entre los mismos hebreos".[5]

Inscripción

_-_Louvre_-_AO_4806_-_picture_08.jpg.webp)

El sarcófago tiene una inscripción de 22 líneas, conocida como KAI-14, escrita en lengua cananea fenicia, en alfabeto fenicio . La inscripción identifica al rey en el interior y advierte a la gente que no perturbe su reposo.[6]

El idioma utilizado en la inscripción es un dialecto cananeo mutuamente inteligible con el hebreo bíblico.

Como en otras inscripciones fenicias, el texto parece no utilizar ninguna o casi ninguna matres lectionis. Como en arameo, la preposición אית (ʾyt) se usa como marcador acusativo, mientras que את (ʾt) se usa para "con".

Texto frontal

La siguiente traducción se basa en la de Julius Oppert,[7] enmendada con la ayuda de una traducción más reciente de Prichard & Fleming.[8]

| Transcripciones | Traducción | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

Galería de imágenes

Visión de cerca de parte de la inscripripción

Visión de cerca de parte de la inscripripción Dibujo de Osman Hamdi Bey

Dibujo de Osman Hamdi Bey Dibujo del lateral superior del sarcófago

Dibujo del lateral superior del sarcófago Dibujo de Jean-Joseph-Léandre Bargès en 1856

Dibujo de Jean-Joseph-Léandre Bargès en 1856 Ubicación actual en el Louvre

Ubicación actual en el Louvre

Referencias

- Lehmann, Reinhard G. (2013). «Wilhelm Gesenius and the Rise of Phoenician Philology». Beihefte zur Zeitschrift für die alttestamentliche Wissenschaft (Berlin / Boston: De Gruyter) 427: 209-266. Archivado desde el original el 4 de marzo de 2016. Consultado el 8 de abril de 2015.

- William Wadden Turner, 3 July 1855, The Sidon Inscription, p.259: "Its interest is greater both on this account and as being the first inscription properly so-called that has yet been found in Phoenicia proper, which had previously furnished only some coins and an inscribed gem.

- Louvre website: "The favor of the Persian king had increased the territory of Sidon by granting it part of Philistine: "The Lord of Kings gave us Dor and Yapho, the rich wheat-lands that are in the Plain of Sharon, in recognition of the great deeds that I accomplished and we have added to the lands that are forever those of the Sidonians.""

- Turner, W. (1860).

- Bargès, Jean-Joseph Léandre (1856), Benjamin Duprat, ed., Mémoire sur le sarcophage et l'inscription funéraire d'Eschmounazar, roi de Sidon (editio princeps edición), p. 39, «Sous le rapport de la linguistique, il nous fournit de précieux renseignements sur la nature de la langue parlée en Phénicie quatre siècles environ avant l'ère chrétienne; cette langue s'y montre identique avec l'hébreu, sauf les inflexions finales de quelques mots et certaines expressions, en très-petit nombre, qui ne se retrouvent pas dans les textes bibliques parvenus jusqu'à nous ; le fait de l'hébreu écrit et parlé à Sidon, à une époque où les Juifs de retour de la captivité n'entendaient déjà plus cette langue, est une preuve qu'elle s'est conservée chez les Phéniciens plus longtemps que chez les Hébreux eux-mêmes. [Translation: With regard to linguistics, it provides us with valuable information on the nature of the language spoken in Phoenicia about four centuries before the Christian era; this language is shown to be identical with Hebrew, except for the final inflections of a few words and certain expressions, in very small numbers, which are not found in the biblical texts which have come down to us; the fact that Hebrew was written and spoken in Sidon, at a time when the Jews returning from captivity no longer heard this language, is proof that it was preserved among the Phoenicians longer than among the Hebrews themselves.] ».

- Cline, Austin. «Sidon Sarcophagus: Illustration of the Sarcophagus of Eshmunazar II Found Near Sidon, Lebanon». About.com. Consultado el 27 de marzo de 2009.

- Samuel Birch, Records of the past: Being English Translations of the Ancient Monuments of Egypt and Western Asia, vol. 9, 1877, p. 111.

- James B. Prichard and Daniel E. Fleming, The Ancient Near East: An Anthology of Texts and Pictures, 2011, p. 311.

- pages 42 "Ifil" and 107 "wyšbn", see Glossary of Phoenician, by Harris, Zellig S.,: A Grammar of the Phoenician Language, New Haven, 1936

Notas

- La línea # 16 "wyšrn" = "establecer" o "colocar" y la línea # 17 "wyšbny" = "establecer" usan la misma raíz, pero el grabador (el Escriba) las escribió de manera diferente. La línea # 16 usó "R" y la línea # 17 usó "B". En la escritura fenicia son similares y aquí podría haber un error del Escriba o de la persona que hizo el dibujo de la inscripción en el siglo XIX. El uso correcto es "wyšbn" y la línea # 16 es el error,

- Sigue el texto de la inscripción de 22 líneas, en la parte frontal del sarcófago, con una transliteración uno a uno al alfabeto hebreo . El texto original no contiene saltos de palabras; estos son simplemente sugeridos; los números aparecen en la inscripción original en un estándar egipcio.

- The eighth month of the Phoenician year which was identical with the Judaic.

- King Eshmunazar lived in the fourth century B.C., this is generally admitted on account of the form of the sarcophagus, which was certainly Egyptian; there are even in the middle of it traces of hieroglyphs which have been erased. The King Tabnit may be the Tennes of Greek authors.

- The seaside Sidon' Sidon eres yam, seems to be one of the two Sidons, the other may have been the Sidon of the mountain. Sennacherib speaks also of the two Sidons, the great and the little one

- The "Lords of the Kings" seem not to be the Kings of Persia, but an epithet applicable to a divine king.

Enlaces externos

- Bargès, l'Abbé Jean-Joseph Léandre (1856), Benjamin Duprat, ed., Mémoire sur le sarcophage et l'inscription funéraire d'Eschmounazar, roi de Sidon, p. 40.

- Descripción en el Louvre

- Imagen GIF de la inscripción .

- Información sobre la inscripción de Eshmunazar (en español) .

- Una fotografía del sarcófago .

- Traducción al inglés de la inscripción