Introduction

Painting during the Song Dynasty (960–1279) reached a new level of sophistication with further development of landscape painting. The shan shui style painting—"shan" meaning mountain and "shui" meaning river—became prominent features in Chinese landscape art. The emphasis laid upon landscape painting in the Song period was grounded in Chinese philosophy: Taoism stressed that humans were but tiny specks among vast and greater cosmos, while Neo-Confucianist writers often pursued the discovery of patterns and principles that they believed caused all social and natural phenomena. While the painting of portraits and closely viewed objects such as birds on branches were held in high esteem by the Song Chinese, landscape painting was paramount.

Techniques

Artists of the time mastered the formula of creating intricate and realistic scenes placed in the foreground, while the background retains qualities of vast and infinite space. Distant mountain peaks rise out of high clouds and mist, while streaming rivers run from afar into the foreground. Immeasurable distances are conveyed through the use of blurred outlines and impressionistic treatment of natural phenomena.

Northern and Southern Song

There was a significant difference in painting trends between the Northern Song period (960–1127) and Southern Song period (1127–1279). The paintings of Northern Song officials were influenced by their political ideals of bringing order to the world and tackling the largest issues affecting the whole of their society; as such, their paintings often depict huge, sweeping landscapes. On the other hand, Southern Song officials were more interested in reforming society from the bottom up and on a much smaller scale, a method they believed had a better chance for eventual success. Hence, their paintings often focus on smaller, visually closer, and more intimate scenes, while the background is often depicted as bereft of detail, as a realm without substance or concern for the artist or viewer.

Snow Mountains by Guo Xi, located in the Shanghai Museum.

Guo Xi, a representative painter of landscape painting in the Northern Song dynasty, has been well known for depicting mountains, rivers and forests in winter. This piece shows a scene of deep and serene mountain valley covered with snow and several old trees struggling to survive on precipitous cliffs. It is a masterpiece of Guo Xi by using light ink and magnificent composition to express his open and high artistic conception.

This change in attitude from one era to the next stemmed largely from the rising influence of Neo-Confucian philosophy. Adherents to Neo-Confucianism focused on reforming society from the bottom up, not the top down, which can be seen in their efforts to promote small private academies during the Southern Song instead of the large state-controlled academies seen in the Northern Song era.

Ma Lin, Listening to the Wind (1246)

Southern Song officials were interested in reforming society from the bottom up and on a small scale. Hence, their paintings often focused on small, visually closer, and more intimate scenes, while the background was often depicted as bereft of detail as a realm without substance or concern for the artist or viewer.

Influential Painters

Ma Yuan and Xia Gui

Ma Yuan was a Southern Song painter of the Song Dynasty. His works, together with that of Xia Gui, formed the basis of the so-called Ma-Xia school of painting and are considered among the finest from the period. Although a very versatile painter, Ma is known today primarily for his landscape scrolls. A characteristic feature of many paintings is the so-called "one-corner" composition, in which the actual subjects of the painting are pushed to a corner or a side, leaving the other part of the painting more or less empty. As court painters, Ma Yuan and Xia Gui used strong black brushstrokes to sketch trees and rocks and pale washes to suggest misty space.

Walking on Path in Spring by Ma Yuan (马远 c.1190 - 1279年))

Ma Yuan was one of the most prominent Chinese painters of the Song Dynasty.

Su Shi and Mi Fu

Painting had become an art of high sophistication, associated with the gentry class as one of their main artistic pastimes (the others being calligraphy and poetry). During the Song Dynasty, there were avid art collectors that would often meet in groups to discuss their own paintings, as well as rate those of their colleagues and friends. The poet and statesman Su Shi (1037–1101) and his accomplice Mi Fu (1051–1107) often partook in these affairs, borrowing art pieces to study, copy, or exchange. They created a new kind of art based upon the three perfections in which they used their skills in calligraphy (the art of beautiful writing) to make ink paintings. From their time onward, many painters strove to freely express their feelings and to capture the inner spirit of their subject instead of describing its outward appearance. The small round paintings popular in the Southern Song were often collected into albums as poets would write poems along the side to match the theme and mood of the painting.

Zhang Zeduan, Yi Yuanji, and Other Court Painters

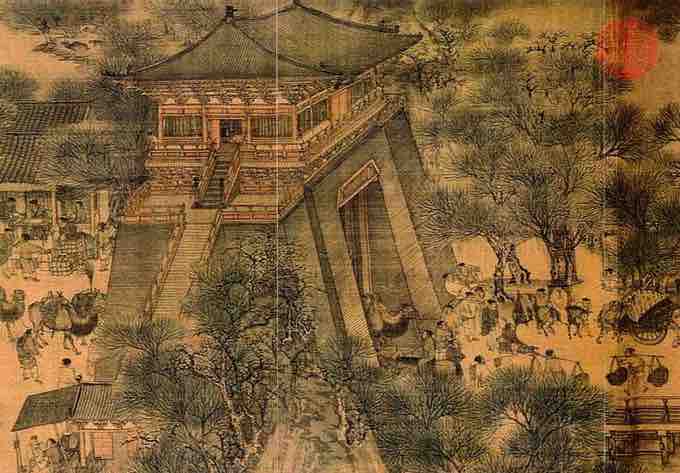

The imperial courts of the emperor's palace were filled with his entourage of court painters, calligraphers, poets, and storytellers. One of the greatest landscape painters given patronage by the Song court was Zhang Zeduan (1085–1145), who painted the original Along the River During Qingming Festival scroll, one of the most well-known masterpieces of Chinese visual art. Emperor Gaozong of Song (1127–1162) commissioned an art project of numerous paintings for the Eighteen Songs of a Nomad Flute, based on the poet Cai Wenji (177–250 AD) of the earlier Han Dynasty. Yi Yuanji achieved a high degree of realism painting animals, in particular monkeys and gibbons.

Detail of the original "Along the River during Qingming Festival" by Zhang Zeduan, early 12th century

Zhang Zeduan was instrumental in the early history of the Chinese landscape art style known as shan shui. Zhang's original painting of the Along the River During the Qingming Festival reveals much about life in China during the 11th-12th century. Its myriad depictions of different people interacting with one another reveals the nuances of class structure and the many hardships of urban life as well. It also displays accurate depictions of technological practices found in Song China.