Overview: The Eastern Woodland Cultures

The Eastern Woodlands cultures inhabited the regions of North America east of the Mississippi River as of 2500 BCE or earlier. Much of their artwork has been preserved through their shared tradition of burying their dead in earthen mounds along with artifacts and tools.

Northeastern Woodlands

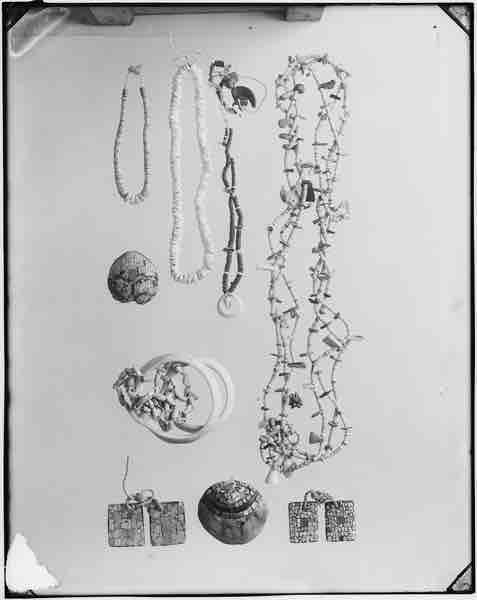

From the 12th century onward, the Iroquois and nearby coastal tribes fashioned wampum from shells and string. "Wampum" is a Wampanoag word referring to the shells themselves, which were used primarily as currency and were highly sought as a trade good throughout the Eastern Woodlands.

Wampum jewelry

Wampum was commonly traded or used as currency by the Iroquois and nearby coastal tribes.

Beadwork was very popular in this region, and Indigenous peoples produced barrel-shaped and discoidal shell beads, as well as perforated small whole shells. Over time, the use of more slender iron drills greatly improved the drilling of holes in small beads. Pendants carved from stone, wood, shells, and incised animal teeth—especially bear teeth—were popular and were typically shaped as animals such as birds, turtles, or fish. Bird motifs were especially common, ranging from the stylized heads of raptors to ducks, as were images of human faces, believed by the Seneca and other tribes to be protective. Pearls were historically inlaid into bear teeth and incorporated into necklaces.

Other arts from the Northeast Woodlands included wood carvings, such as False Face masks used by Iroquois people in healing rituals. Iroquois artists carved ornamental hair combs from antlers, making increasingly elaborate designs with the introduction of metal knives from Europe in the late 16th and 17th centuries. Europeans also introduced silversmithing to the northeast in the mid-17th century, and today there are several active Iroquois silversmiths.

Southeastern Woodlands

Mississippian Culture

The Mississippian culture flourished from approximately 800-1500 CE in what is now the Midwestern, Eastern, and Southeastern United States. Pottery is one of the hallmark arts of this culture, which includes the Cahokia, Natchez, Caddo, Choctaw, Muscogee Creek, Wichita, and many other southeastern peoples. One of the defining marks of Mississippian culture pottery is its use of more advanced ceramic techniques, such as the use of ground mussel shell as a tempering agent in the clay paste. Textile making (such as the common patchwork clothing worn by indigenous people) and doll-making were also common crafts.

Mississippi pottery

A human head effigy pot from the Mississippian culture, on display at the Hampson Museum State Park in Wilson.

Many artisans from this area were involved with the Southeastern Ceremonial Complex, a pan-regional and pan-linguistic religious and trade network. The majority of the information known about the Southeastern Ceremonial Complex is derived from the elaborate artworks its participants left behind, including pottery, shell gorgets and cups, stone statuaries, and copper plates. With the invasion of the Europeans and the diseases they introduced, many of the societies collapsed and ceased to practice a Mississippian lifestyle.

Cherokee shell gorget

A contemporary shell gorget carved by Bennie Pokemire (Eastern Band Cherokee)

In 1896, more than 1,000 carved and painted wooden objects—including masks, tablets, plaques, and effigies—were excavated in Key Marco, southwestern Florida. They have since been described as some of the finest prehistoric Native American art in North America. Spanish missionaries described similar masks and effigies in use by the Calusa late in the 17th century, although no examples of the Calusa objects from the historic period have survived.

Fort Ancient Culture

In addition to Mississippi culture, Fort Ancient was a Native American culture that flourished from 1000-1750 CE among a people who predominantly inhabited land along the Ohio River. Fort Ancient women used a technique known as coiling to make their pottery, in which they rolled clay into long, rounded strips. They then layered these strips one on top of another to mold the vessel, smoothing the inside of the vessel with a smooth round stone and the outside with a wooden paddle. Pottery from this period was distinguished by thinner walls than preceding Woodland pottery, and common shapes included large plain cooking jars with straps or loop handles. Fort Ancient pottery was often engraved with decorations on the rim and neck of the vessels, consisting of a series of interlocking lines, called guilloché.

Traditional dress often incorporated elaborate designs and decorations. For example, Choctaw women's dance regalia incorporated ornamental silver combs and openwork beaded collars, and Caddo women wore hourglass-shaped hair ornaments called dush-tohs.

Clay, stone, and pearl beads were fashioned and worn by the people of the Southeastern Woodlands, often decorated with bold imagery. As in the North, European contact introduced glass beads and silversmithing technology, and silver and brass armbands and gorgets became popular among Southeastern men in the 18th and 19th centuries. Sequoyah became one of the first well-known Cherokee silversmiths in the 18th and 18th centuries.