Northwest Coast Art

Northwest Coast art is the term commonly applied to a style of art created primarily by artists from Tlingit, Haida, Tsimshian, Kwakwaka'wakw, Nuu-chah-nulth, and other First Nations and Native American tribes along the Northwest Coast of North America, from pre-European-invasion times up to the present. Art from this region is historically distinguished by complex woodcarvings and the use of formlines, or the use of characteristic shapes referred to as ovoids, "U" forms, and "S" forms.

Woodcarvings

Before European invasion, the most common media were wood (often Western red cedar), stone, and copper; since European contact, paper, canvas, glass, and precious metals have also been used. If paint was used to decorate an object, the most common colors were traditionally red and black, though yellow was often used as well, particularly among Kwakwaka'wakw artists. Woodcarving from this region is characterized by an extremely complex style. The most famous examples include Totem poles, Transformation masks, and canoes.

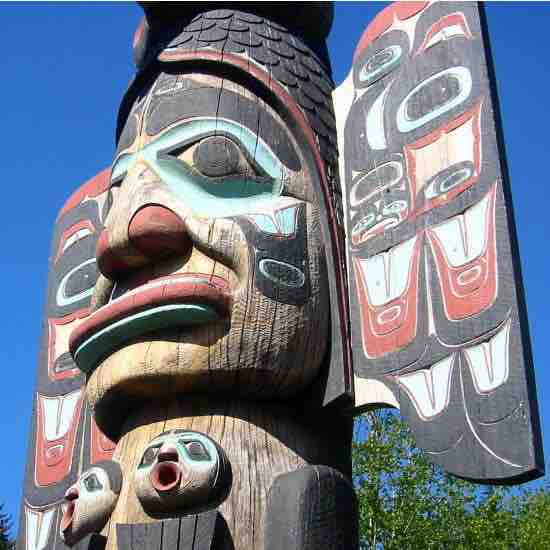

Totem Pole from the Northwest

Native American Totem Pole from Ketchikan, Alaska.

Totem Poles

Totem poles are monumental sculptures carved on poles, posts, or pillars with symbols or figures made from large trees (mostly western red cedar) by indigenous peoples of the Pacific Northwest coast. The word totem derives from the Algonquian (most likely Ojibwe) word odoodem, "his kinship group". The carvings may symbolize or commemorate cultural beliefs that recount familiar legends, clan lineages, or notable events. The poles may also serve as functional architectural features, welcome signs for village visitors, or mortuary vessels for the remains of deceased ancestors. Given the complexity and symbolic meanings of totem pole carvings, their placement and importance lies in the observer's knowledge and connection to the meanings of the figures.

Totem pole carvings were likely preceded by a long history of decorative carving, with stylistic features borrowed from smaller prototypes. Eighteenth-century European invaders documented the existence of decorated interior and exterior house posts prior to 1800. United States governmental policies and practices of acculturation and assimilation sharply reduced totem pole production by the end of 19th century. Renewed interest from tourists, collectors, and scholars in the 1880s and 1890s helped document and collect the remaining totem poles, but nearly all totem pole making had ceased by 1901. Twentieth-century revivals of the craft, additional research, and continued support from the public have helped establish new interest in this regional artistic tradition.

Weaving and Other Art Forms

Chilkat weaving applied formline designs to their textiles. Tlingit, Haida, and Tsimshian have traditionally produced Chilkat woven regalia from wool and yellow cedar bark, using them for civic and ceremonial events.

Chilkat blanket

In the collection of the University of Alaska Museum, Fairbanks

The patterns depicted in most forms of art include natural forms, such as bears, ravens, eagles, orcas, and humans; legendary creatures, such as thunderbirds and sisiutls; and abstract forms made up of the characteristic Northwest Coast shapes. Northwest Coast designs were often used to decorate traditional household items, such as spoons, ladles, baskets, hats, and paddles; following European contact, the Northwest Coast art style has increasingly been used in gallery-oriented forms, such as paintings, prints, and sculptures.

Impact of Europeans

After European invasion in the late 18th century, the people who produced Northwest Coast art suffered huge population losses due to diseases, such as smallpox, and cultural losses due to assimilation into European-North American culture. The production of their art dropped off drastically as well. Toward the end of the 19th century, Northwest Coast artists began producing work for commercial sale, such as small argillite carvings. The end of the 19th century also saw large-scale export of totem poles, masks, and other traditional art objects from the region to museums and private collectors around the world. Some of this export was accompanied by financial compensation to people who had a right to sell the art, though a great deal was not.

In the early 20th century, very few First Nations artists in the Northwest Coast region were producing art. A tenuous link to older traditions remained in artists such as Charles Gladstone and Mungo Martin. The mid-20th century saw a revival of interest and production of Northwest Coast art due to the influence of artists and critics, such as Bill Reid, a grandson of Charles Gladstone. It also saw an increasing demand for the return of art objects that were illegally taken from First Nations communities—a demand which continues to the present day. Today, there are numerous art schools teaching formal Northwest Coast art of various styles, and there is a growing market for new art in this style.