Overview: Aztec Codices

The Aztec codices are manuscripts that were written and painted by tlacuilos (codex creators). One of the best primary sources of information on Aztec culture, they served as calendars, ritual texts, almanacs, maps, and historical manuscripts of the Aztec people, spanning from before the Spanish conquest through the colonial era. Pre-colonial codices differ from colonial codices in that they are largely pictorial and not meant to symbolize spoken or written narratives. The colonial-era codices not only contain Aztec pictograms, but also Classical Nahuatl (in the Latin alphabet), Spanish, and occasionally Latin.

Scholars now have access to a body of around 500 colonial-era codices, as well as a limited number of pre-colonial codices, though there are very few surviving codices from the pre-colonial era. While the tradition of codex-painting endured over the transition to colonial culture, codex production declined under the control of Spanish authorities, suggesting Spanish influence or even censorship in codex production.

Well-known Codices

Codex Borbonicus

The Codex Borbonicus is a codex written by Aztec priests around the time of the Spanish conquest of Mexico. Like all pre-colonial codices, it was originally entirely pictorial in nature, although some Spanish descriptions were later added. It is a single 46.5-foot long sheet of paper made from amatl (fig bark); although there were originally 40 accordion-folded pages, the first two and the last two pages are missing.

Codex Borbonicus can be divided into three sections. The first section is one of the most intricate surviving divinatory calendars (or tonalamatl), and most of the page is taken up with a painting of the ruling deity or deities. With the symbols of the calendar, divided into 13-day periods, Aztec priests were able to create horoscopes and divine the future. The second section documents the Mesoamerican 52-year cycle, showing in order the dates of the first days of each of these 52 solar years. The third section is focused on rituals and ceremonies, particularly those that end the 52-year cycle, when the "new fire" must be lit.

Page thirteen of the Aztec Codex Borbonicus

The original page thirteen of the Codex Borbonicus shows the 13th trecena (or 13-day period) of the Aztec sacred calendar. This 13th trecena was under the auspices of the goddess Tlazolteotl, who is portrayed wearing a flayed skin, giving birth to Cinteotl.

The Boturini Codex

The Boturini Codex was painted by an unknown Aztec author some time between 1530 and 1541, roughly a decade after the Spanish conquest of Mexico. It tells the story of the legendary Aztec journey from Aztlán to the Valley of Mexico. Rather than employing separate pages, the author used one long, folded sheet of amatl (fig bark).

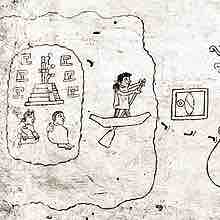

Detail of first page from the Boturini Codex.

The first page of this Aztec codex depicts the departure from Aztlán.

The Florentine Codex

The Florentine Codex is perhaps the most useful source of information on Aztec life in the years before the Spanish conquest, even though the complete copy of the codex was not published until 1979. Prior to this, only a censored Spanish translation had been available. The codex is a set of 12 books created under the supervision of Bernardino de Sahagún between approximately 1540 and 1585. De Sahagún worked with the surviving Aztec wise men and taught tlacuilos to write the original Nahuatl accounts using the Latin alphabet. Because of fear of the Spanish authorities, he maintained the anonymity of his informants and wrote a heavily censored version in Spanish.

Codex Osuna

The Codex Osuna is a set of seven separate documents created in early 1565 to present evidence against the government of Viceroy Luis de Velasco during the 1563-66 inquiry by Jerónimo de Valderrama. In this codex, indigenous leaders claim non-payment for various goods and for various services performed by their people, including construction and domestic help.

The Aubin Codex

The Aubin Codex is a pictorial history of the Aztecs from their departure from Aztlán through the Spanish conquest to the early Spanish colonial period, ending in 1607. Consisting of 81 leaves, it was most likely started in 1576. It is also known as the "Manuscrito de 1576" ("The Manuscript of 1576"). Among other topics, the Aubin Codex has a native description of the massacre at the temple in Tenochtitlan in 1520.

Codex Magliabechiano

The Codex Magliabechiano, named after 17th century manuscript collector Antonio Magliabechi, was created during the mid-16th century. Primarily a religious document, it depicts the 20 day-names of the tonalpohualli, the 18 monthly feasts, the 52-year cycle, and various deities, indigenous religious rites, costumes, and cosmological beliefs.

Other Codices

- The Codex Mendoza was composed around 1541. It is divided into three sections: a history of each Aztec ruler and their conquest, a list of the tribute paid by each tributary province, and a general description of daily Aztec life.

- The Codex Cozcatzin, dated 1572, lists historical and genealogical information focused on Tlatelolco and Tenochtitlan. The final page consists of astronomical descriptions in Spanish.

- The Codex Ixtlilxochitl is an early 17th century codex fragment detailing, among other subjects, a calendar of the annual festivals and rituals celebrated by the Aztec teocalli during the Mexican year. Each of the 18 months is represented by a god or historical character.

- The Libellus de Medicinalibus Indorum Herbis ("Little Book of the Medicinal Herbs of the Indians") is an herbal manuscript describing the medicinal properties of various plants used by the Aztecs. The Libellus is also known as the Badianus Manuscript, the Codex de la Cruz-Badiano, or the Codex Barberini.