Overview

Raphael (1483–1520) was an Italian painter and architect of the High Renaissance. His work is admired for its clarity of form and ease of composition and for its visual achievement of the Neoplatonic ideal of human grandeur. Together with Michelangelo and Leonardo da Vinci, Raphael forms the traditional trinity of great masters of that period. He was enormously productive, running an unusually large workshop; despite his death at 30, a large body of his work remains among the most famous of High Renaissance art.

Influences

Some of Raphael's most striking artistic influences come from the paintings of Leonardo da Vinci. In response to da Vinci's work, in some of Raphael's earlier compositions he gave his figures more dynamic and complex positions. For example, Raphael's Saint Catherine of Alexandria (1507) borrows from the contrapposto pose of da Vinci's Leda and the Swans.

Saint Catherine of Alexandria

Saint Catherine of Alexandria (1507) borrows from the contrapposto pose of da Vinci's Leda.

While Raphael was also aware of Michelangelo's works, he deviates from his style. In his Deposition of Christ, Raphael draws on classical sarcophagi to spread the figures across the front of the picture space in a complex and not wholly successful arrangement.

The Deposition by Raphael, 1507

The Stanze Rooms and the Loggia

In 1511, Raphael began work on the famous Stanze paintings, which made a stunning impact on Roman art, and are generally regarded as his greatest masterpieces. The Stanza della Segnatura contains The School of Athens, Poetry, Disputa, and Law. The School of Athens, depicting Plato and Aristotle, is one of his best known works. These very large and complex compositions have been regarded ever since as among the supreme works of the High Renaissance, and the "classic art" of the post-antique West. They give a highly idealized depiction of the forms represented, and the compositions—though very carefully conceived in drawings—achieve sprezzatura, a term invented by Raphael's friend Castiglione, who defined it as "a certain nonchalance that conceals all artistry and makes whatever one says or does seem uncontrived and effortless."

View of the Stanze della Segnatura, frescoes painted by Raphael.

In the later phase of Raphael's career, he designed and painted the Loggia at the Vatican, a long thin gallery that was open to a courtyard on one side and decorated with Roman style grottesche. He also produced a number of significant altarpieces, including The Ecstasy of St. Cecilia and the Sistine Madonna. His last work, on which he was working until his death, was a large Transfiguration which, together with Il Spasimo, shows the direction his art was taking in his final years, becoming more proto-Baroque than Mannerist.

The Master's studio

Raphael ran a workshop of over 50 pupils and assistants, many of whom later became significant artists in their own right. This was arguably the largest workshop team assembled under any single old master painter, and much higher than the norm. They included established masters from other parts of Italy, probably working with their own teams as sub-contractors, as well as pupils and journeymen.

Architecture

In architecture, Raphael's skills were employed by the papacy and wealthy Roman nobles. For instance, Raphael designed the plans for the the Villa Madama, which was to be a lavish hillside retreat for Pope Clement VII (and was never finished). Even incomplete, Raphael's schematic was the most sophisticated villa design yet seen in Italy, and greatly influenced the later development of the genre. It also appears to be the only modern building in Rome of which Palladio made a measured drawing.

Draftsman

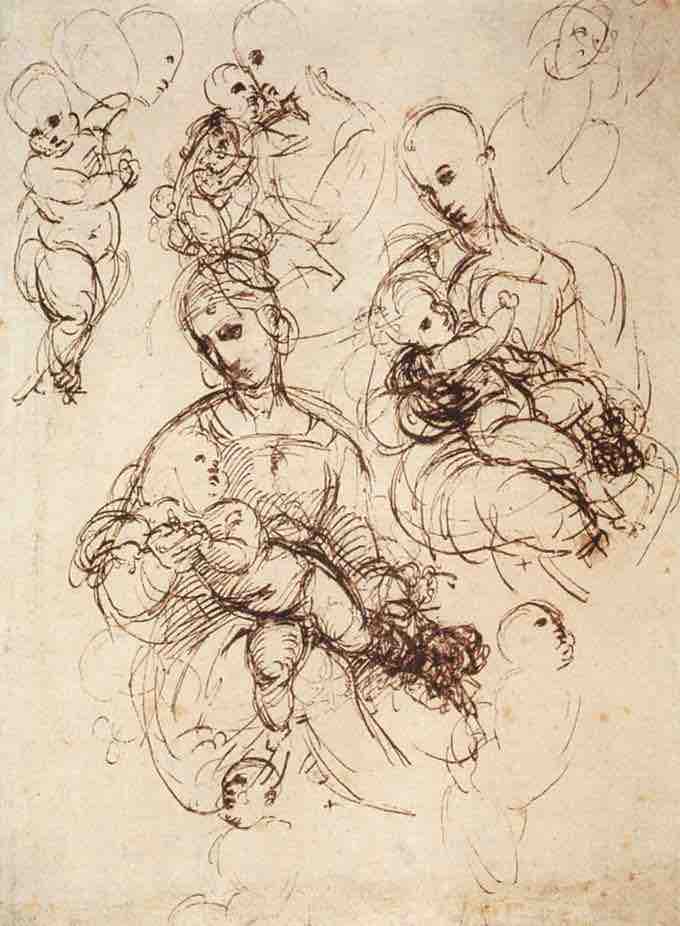

Raphael was one of the finest draftsmen in the history of Western art, and used drawings extensively to plan his compositions. According to a near-contemporary, when beginning to plan a composition, he would lay out a large number of his stock drawings on the floor, and begin to draw "rapidly," borrowing figures from here and there. Over 40 sketches survive for the Disputa in the Stanze, and there may well have been many more originally (over 400 sheets survived altogether).

As evidenced in his sketches for the Madonna and Child, Raphael used different drawings to refine his poses and compositions, apparently to a greater extent than most other painters. Most of Raphael's drawings are rather precise—even initial sketches with naked outline figures are carefully drawn, and later drawings often have a high degree of finish, with shading and sometimes highlights in white. They lack the freedom and energy of some of da Vinci's and Michelangelo's sketches, but are almost always very satisfying aesthetically.

Raphael Sketch

This drawing shows Raphael's efforts in developing the composition for the Madonna and Child.