After their persecution ended in the fourth century, Christians began to erect buildings that were larger and more elaborate than the house churches in which they had been worshiping. However, what emerged was an architectural style distinct from classical pagan forms. Architectural formulas for temples were deemed unsuitable. This was not simply for their pagan associations, but because pagan cult and sacrifices occurred outdoors under the open sky in the sight of the gods. The temple, housing the cult figures and the treasury, served as a backdrop. Therefore, Christians began using the model of the basilica, which had a central nave with one aisle at each side and an apse at one end.

Old St. Peter's and the Western Basilica

The basilica model was adopted in the construction of "Old" St. Peter's church in Rome. (What stands today is "New" St. Peter's, which replaced the original during the Italian Renaissance.) Whereas the original Roman basilica was rectangular with at least one apse, usually facing North, Christian builders made several symbolic modifications. Between the nave and the apse, they added a transept, which ran perpendicular to the nave. This addition gave the building a cruciform shape to memorialize the Crucifixion. The apse, which held the altar and the Eucharist, now faced East, in the direction of the rising sun. However, the apse of Old St. Peter's faced West to commemorate the church's namesake, who, according to the popular narrative, was crucified upside down.

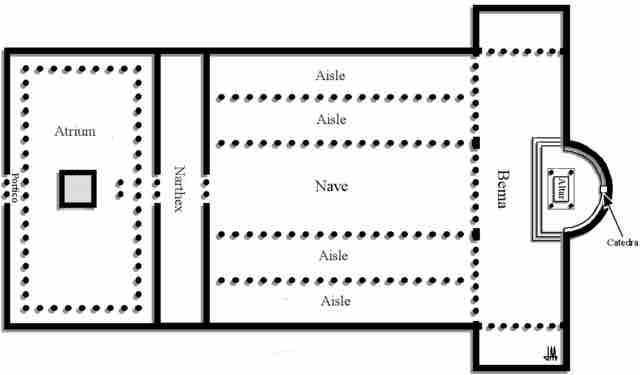

Plan of "Old" St. Peter's Basilica.

One of the first Christian churches in Rome, Old St. Peter's followed the plan of the Roman basilica and added a transept (labeled "Bema" in this diagram) to give the church a cruciform shape.

Exterior reconstruction of Old St. Peter's

This reconstruction depicts an idea of how the church appeared in the fourth century.

A Christian basilica of the fourth or fifth century stood behind its entirely enclosed forecourt. It was ringed with a colonnade or arcade, like the stoa or peristyle that was its ancestor, or like the cloister that was its descendant. This forecourt was entered from outside through a range of buildings along the public street. In basilicas of the former Western Roman Empire, the central nave is taller than the aisles, forming a row of windows called a clerestory. In the Eastern Empire (also known as the Byzantine Empire, which continued until the fifteenth century), churches were centrally planned. The Church of San Vitale in Ravenna, Italy is prime example of an Eastern church.

San Vitale

The church of San Vitale is highly significant in Byzantine art, as it is the only major church from the period of the Eastern Emperor Justinian I to survive virtually intact to the present day. While much of Italy was under the rule of the Western Emperor, Ravenna came under the rule of Justinian I in 540.

San Vitale

Unlike Western churches like St. Peter's, San Vitale consists of a central dome surrounded by two ambulatories. This is known as a centrally-planned church.

The church was begun by Bishop Ecclesius in 527, when Ravenna was under the rule of the Ostrogoths, and completed by the twenty-seventh Bishop of Ravenna, Maximian, in 546 during the Byzantine Exarchate of Ravenna. The architect or architects of the church is unknown. The construction of the church was sponsored by a Greek banker, Julius Argentarius, and the final cost amounted to 26,000 solidi (gold pieces). The church has an octagonal plan and combines Roman elements (the dome, shape of doorways, and stepped towers) with Byzantine elements (polygonal apse, capitals, and narrow bricks). The church is most famous for its wealth of Byzantine mosaics, the largest and best preserved outside of Constantinople.

The central section is surrounded by two superposed ambulatories, or covered passages around a cloister. The upper one, the matrimoneum, was reserved for married women. A series of mosaics in the lunettes above the triforia depict sacrifices from the Old Testament. On the side walls, the corners, next to the mullioned windows, have mosaics of the Four Evangelists, under their symbols (angel, lion, ox and eagle), who are dressed in white. The cross-ribbed vault in the presbytery is richly ornamented with mosaic festoons of leaves, fruit, and flowers, converging on a crown encircling the Lamb of God. The crown is supported by four angels, and every surface is covered with a profusion of flowers, stars, birds, and animals, specifically many peacocks. Above the arch, on both sides, two angels hold a disc. Beside them are representations of the cities of Jerusalem and Bethlehem. These two cities symbolize the human race.

The Presbytery

The cross-ribbed vault in the presbytery is richly ornamented with mosaic festoons of leaves, fruit and flowers, converging on a crown encircling the Lamb of God.