Mount Vesuvius and the Preservation of Pompeiian Architecture

During the Roman Republic and into the early Empire, the area today known as the Bay of Naples was developed as a resort-type area for elite Romans escaping the pressure and politics of Rome. The region was dominated by Mt. Vesuvius, which famously erupted in August 79 CE, burying and preserving the cities of Herculaneum, Pompeii, along with the region's villas and farms. When Vesuvius erupted on August 25, a cloud of ash spewed south, burying the cities of Pompeii, Nuceria, and Stabiae. While not everyone left prior to the eruption, archaeological evidence shows that people did leave the city. Some houses give the impression of having been packed up and in some cases furniture and objects were excavated jumbled together. Other objects of value appear to have been buried or hidden. There is evidence of people returning after the eruption to dig through the remains— either recovering lost goods or looting for valuables.

Eruption of Mount Vesuvius

The black and gray areas show the direction in which the wind blew the ash and pyroclastic clouds.

In Pompeii, an ash flow suffocated the remaining population and allowed all organic matter to decompose. However, where bodies and other organic objects (from bodies to wooden architectural frames) once lay or stood, empty cavities within the ash remained and preserved their outer forms. A pyroclastic flow of superheated gas and rock went west to the coast and the city of Herculaneum. Unlike the ash blanket of Pompeii, the pyroclastic flow in Herculaneum petrified organic material, ensuring the preservation of human remains and wood, including the preservation of wooden screens, beds, and shelving. Many of the frescoes, mosaics, and other non-organic materials in both ash and pyroclastic flow were preserved until their excavation in the modern period.

The Roman Domus

The Roman domus, or house, played two important roles in Roman society, serving both as a home and as a place of business for patricians and wealthy Romans. To facilitate this dual functionality, the domus had a distinct set of rooms that could be used as either public or private spaces. While no modern domus adheres to the standard model of a domus, many Roman houses, both small and large, have nearly all of these different rooms.

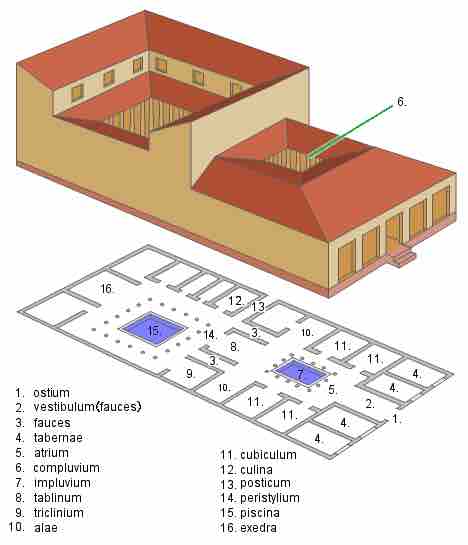

Roman Domus

A standard plan of a Roman domus.

The design of the domus reflects the Roman patronage where a client is protected by a wealthy patron, and in return supports the actions and estate of the patron. Many of a patron's clients would be freedmen or other plebeians and lesser patricians. The domus is often set back from the main street, an tabernae (shops) line the streets on either side of the house's main entrance. Clients entered the house through the fauces (Latin for "jaw"), which was a narrow entryway into an atrium. The atrium was the most important part of the house as the spot where clients and guests were greeted. It often included an impluvium, or basin that collected rain water. The roof did not cover the impluvium. The open space above the basin was called the compluvium. The atrium was often richly decorated with thematic frescos and images of the patron's ancestors. Cubicula, or rooms, lined the atrium, and at the far end was the tablinum. The tablinum functioned as the office of the patron and was where he met with his clients during the morning ritual of salutatio. The tablinum often provided a glimpse into the private sphere of the house, which was set behind the office.

Typically, the front half of the house served as public space, while the back of the domus was reserved for more private functions of the family. In the back of the house, beyond the tablinum, would be one or more triclinium (plural: triclinia), or dining rooms. Dining rooms were lavishly decorated and typically furnished with dining couches and a low table. A peristyle -- a colonnaded courtyard -- was usually the main feature of the back of the house. It could contain gardens and even a pool and provided light as well as shade and breeze for hot summer days. Other features of the domus, include alae (open rooms) with an unknown function, kitchens (culina), and additional rooms for work, sleeping, and servants.

Domus at Pompeii

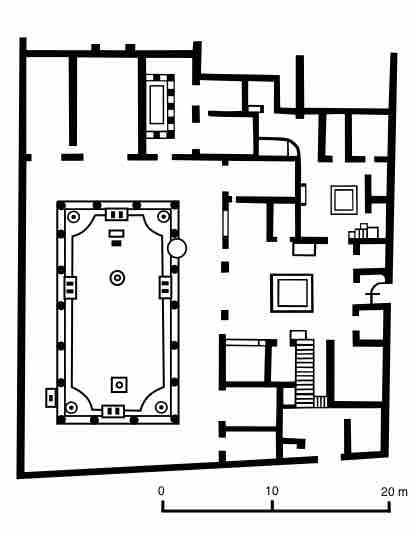

Each domus throughout Pompeii represents the various ways the standard components of a domus were used to create unique floor plans that showcase the status and wealth of the owner. The large complex of the House of the Faun encompasses an entire city block . This domus has two atria, each with its own fauces, although with two peristyles of different sizes. In essence, the House of the Faun was a private villa despite its urban setting.

House of the Faun

Ground plan of the House of the Faun. Pompeii, Italy.

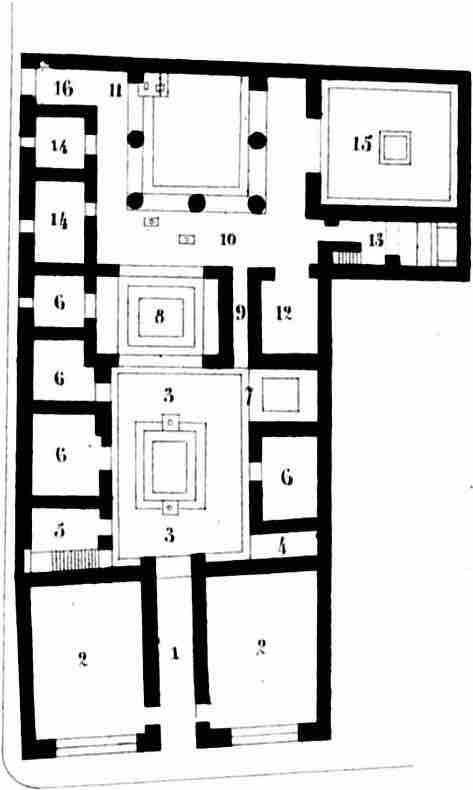

Two houses, the House of the Vettii and the House of the Tragic Poet -- both discussed for their wall paintings -- are simpler constructions than the House of the Faun, but both house plans still readily depict the wealth of the household. Visitors entering the House of the Vettii were greeted by a frescoed image of Priapus, an image that portrayed the wealth and luck of the two bachelors who lived inside. The main attributes of their house were the atrium and the large garden peristyle, surrounded by decorated triclinium and a garden complete with fountains, statues, and flowers. While this house had fewer public-private access restrictions than the standard domus, it did include the main attributes of a traditional Roman house.

House of the Vettii

Ground plan of the House of the Vettii. Pompeii, Italy.

The House of the Tragic Poet was small but maintained the public-private access characteristic of the traditional domus. The fauces was especially noted for its mosaic image of a dog, complete with the warning "Cave canem," or, roughly, "Beware of dog." The fauces led the guest into the atrium and the tablinum, which divided the public front of the house from the private back of the house, where a small peristyle and a frescoed triclinium were located.

House of the Tragic Poet

Ground plan of the House of the Tragic Poet.

Public Architecture

The ash cloud that blanketed Pompeii in 79 CE preserved public buildings, as well as domi. Among the best preserved are the amphitheatre, the Temple of Isis, and the Suburban Baths.

Amphitheatre of Pompeii

The Amphitheatre of Pompeii is the oldest surviving Roman amphitheatre. Built around 70 BCE, the current amphitheatre is the earliest Roman amphitheatre known to have been built of stone. Previous amphitheaters were constructed of wood. The design is seen by some modern crowd control specialists as near optimal. Similar to the Colosseum, constructed over a century later, its arcaded exterior appears to have been conducive to efficient evacuation. Its washroom, located in the neighboring wrestling school has also been cited as an inspiration for better bathroom design in modern stadiums.

Amphitheatre of Pompeii, exterior

Built c. 70 BCE.

Derived from the Greek words amphi (on both sides) and theatron (a place for viewing), an amphitheatre combines two theatres into a circular or ovoid form. The interior of the amphitheatre at Pompeii resembles two Greek theatres, with its tiered seating overlooking a central staging area. Still structurally and acoustically sound, the amphitheatre was the site of notable rock concerts in 1971 and 2016.

Amphitheatre of Pompeii, interior

The interior, with its tiered seating, shows the influence of Greek designs.

Temple of Isis

Roman culture was accommodating of most religions beliefs of its conquered peoples, often building temples and sanctuaries to non-Roman deities and incorporating them into their own pantheon. One such example is the Temple of Isis, dedicated to the Egyptian mother goddess. Principal devotees of this temple are assumed to be women, freedmen, and slaves. Initiates of the Isis mystery cult worshiped a compassionate goddess who promised eventual salvation and a perpetual relationship throughout life and after death.

The temple's design combines Roman, Greek, and Egyptian architectural elements. It is surrounded by brick columns faced with plaster in a stylized reed motif often found on Egyptian columns, Their general shape recalls both the Doric and Tuscan orders. Like typical Roman temples, the portico and cella rest on a raised platform connected to the ground by a central stairway. The columns on the portico appear to have been Tuscan. To either side of the cella is an arched niche flanked by either Corinthian or Composite pillasters.

Temple of Isis

Pompeii, Italy. c. 62 CE.

Suburban Baths

The Suburban Baths (c. late first century BCE), built against the city walls, served as a public bath house to the residents of Pompeii. The entrance to the Baths is through a long corridor that leads into the dressing room. Excavation of the Baths revealed only one set of dressing rooms and has led archaeologists to believe that both men and women shared this facility. The dressing room then led to the tepidarium (lukewarm room), followed by the caldarium (hot room), both of which were standard in public baths throughout the empire.

Suburban Baths, exterior.

Pompeii, Italy. Late first century BCE.