Vertebrate Digestive Systems

Vertebrates have evolved more complex digestive systems to adapt to their dietary needs. Some animals have a single stomach, while others have multi-chambered stomachs. Birds have developed a digestive system adapted to eating un-masticated (un-chewed) food.

Monogastric: Single-chambered Stomach

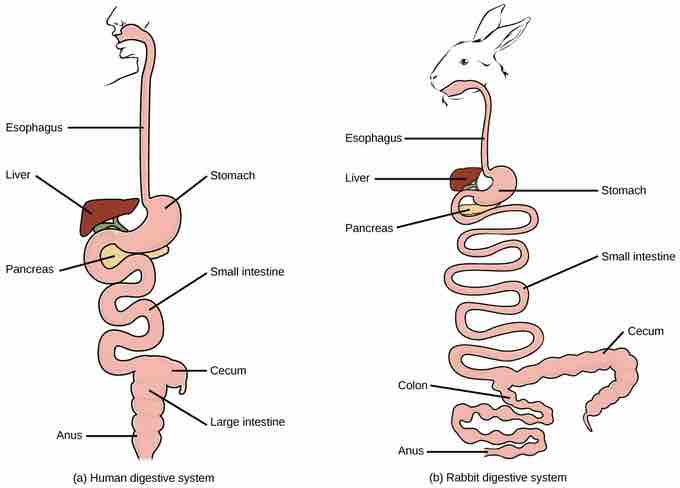

As the word monogastric suggests, this type of digestive system consists of one ("mono") stomach chamber ("gastric"). Humans and many animals have a monogastric digestive system . The process of digestion begins with the mouth and the intake of food. The teeth play an important role in masticating (chewing) or physically breaking down food into smaller particles. The enzymes present in saliva also begin to chemically break down food. The esophagus is a long tube that connects the mouth to the stomach. Using peristalsis, the muscles of the esophagus push the food towards the stomach. In order to speed up the actions of enzymes in the stomach, the stomach has an extremely acidic environment, with a pH between 1.5 and 2.5. The gastric juices, which include enzymes in the stomach, act on the food particles and continue the process of digestion. In the small intestine, enzymes produced by the liver, the small intestine, and the pancreas continue the process of digestion. The nutrients are absorbed into the blood stream across the epithelial cells lining the walls of the small intestines. The waste material travels to the large intestine where water is absorbed and the drier waste material is compacted into feces that are stored until excreted through the rectum.

Mammalian digestive system (non-ruminant)

(a) Humans and herbivores, such as the (b) rabbit, have a monogastric digestive system. However, in the rabbit, the small intestine and cecum are enlarged to allow more time to digest plant material. The enlarged organ provides more surface area for absorption of nutrients.

Avian

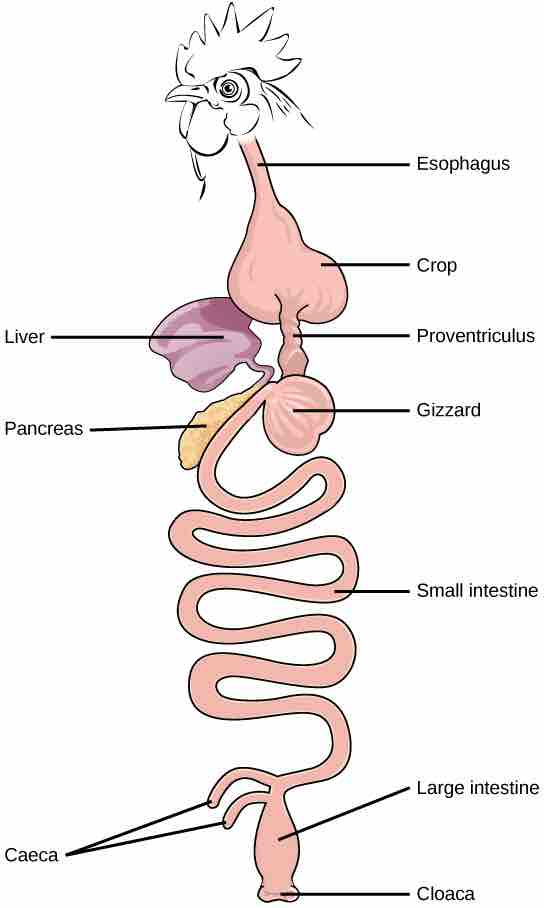

Birds face special challenges when it comes to obtaining nutrition from food. They do not have teeth, so their digestive system must be able to process un-masticated food . Birds have evolved a variety of beak types that reflect the vast variety in their diet, ranging from seeds and insects to fruits and nuts. Because most birds fly, their metabolic rates are high in order to efficiently process food while keeping their body weight low. The stomach of birds has two chambers: the proventriculus, where gastric juices are produced to digest the food before it enters the stomach, and the gizzard, where the food is stored, soaked, and mechanically ground. The undigested material forms food pellets that are sometimes regurgitated. Most of the chemical digestion and absorption happens in the intestine, while the waste is excreted through the cloaca.

Bird digestive system

The avian esophagus has a pouch, called a crop, which stores food. Food passes from the crop to the first of two stomachs, called the proventriculus, which contains digestive juices that break down food. From the proventriculus, the food enters the second stomach, called the gizzard, which grinds food. Some birds swallow stones or grit, which are stored in the gizzard, to aid the grinding process. Birds do not have separate openings to excrete urine and feces. Instead, uric acid from the kidneys is secreted into the large intestine and combined with waste from the digestive process. This waste is excreted through an opening called the cloaca.

Ruminants

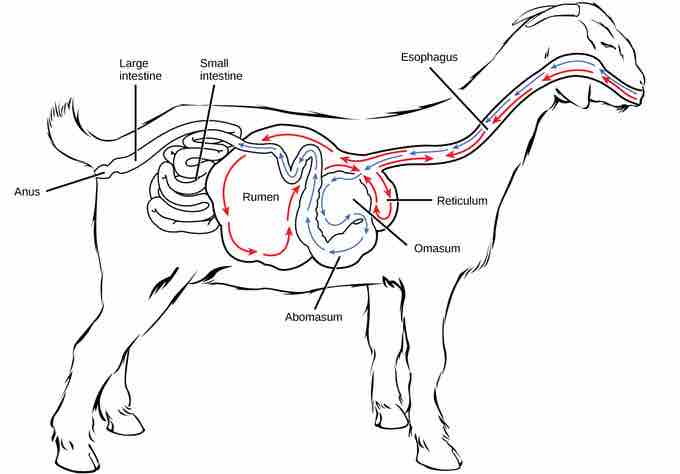

Ruminants are mainly herbivores, such as cows, sheep, and goats, whose entire diet consists of eating large amounts of roughage or fiber. They have evolved digestive systems that help them process vast amounts of cellulose. An interesting feature of the ruminants' mouth is that they do not have upper incisor teeth. They use their lower teeth, tongue, and lips to tear and chew their food. From the mouth, the food travels through the esophagus and into the stomach.

To help digest the large amount of plant material, the stomach of the ruminants is a multi-chambered organ . The four compartments of the stomach are called the rumen, reticulum, omasum, and abomasum. These chambers contain many microbes that break down cellulose and ferment ingested food. The abomasum, the "true" stomach, is the equivalent of the monogastric stomach chamber. This is where gastric juices are secreted. The four-compartment gastric chamber provides larger space and the microbial support necessary to digest plant material in ruminants. The fermentation process produces large amounts of gas in the stomach chamber, which must be eliminated. As in other animals, the small intestine plays an important role in nutrient absorption, while the large intestine aids in the elimination of waste.

Ruminant mammal digestive system

Ruminant animals, such as goats and cows, have four stomachs. The first two stomachs, the rumen and the reticulum, contain prokaryotes and protists that are able to digest cellulose fiber. The ruminant regurgitates cud from the reticulum, chews it, and swallows it into a third stomach, the omasum, which removes water. The cud then passes onto the fourth stomach, the abomasum, where it is digested by enzymes produced by the ruminant.

Pseudo-ruminants

Some animals, such as camels and alpacas, are pseudo-ruminants. They eat a lot of plant material and roughage. Digesting plant material is not easy because plant cell walls contain the polymeric sugar molecule cellulose. The digestive enzymes of these animals cannot break down cellulose, but microorganisms present in the digestive system can. Since the digestive system must be able to handle large amounts of roughage and break down the cellulose, pseudo-ruminants have a three-chamber stomach. In contrast to ruminants, their cecum (a pouched organ at the beginning of the large intestine containing many microorganisms that are necessary for the digestion of plant materials) is large. This is the site where the roughage is fermented and digested. These animals do not have a rumen, but do have an omasum, abomasum, and reticulum.