Employment Levels

Full Employment Defined

Employment levels are one of the most important economic indicators available. Full employment, in macroeconomics, is the level of employment rates when there is no cyclical unemployment. It is defined by the majority of mainstream economists as being an acceptable level of natural unemployment above 0%, the discrepancy from 0% being due to non-cyclical types of unemployment. Unemployment above 0% is advocated as necessary to control inflation, which has brought about the concept of the Non-Accelerating Inflation Rate of Unemployment (NAIRU). Governments that follow NAIRU are attempting to keep unemployment at certain levels (usually over 4%, and as high as 10% or more) by keeping interest rates high. The majority of mainstream economists mean NAIRU when speaking of full employment.

What most economists mean by full employment is a rate somewhat less than 100%, considering slightly lower levels desirable. For example, the 20th century British economist, William Beveridge, stated that an unemployment rate of 3% was full employment. Other economists have provided estimates between 2% and 13%, depending on the country, time period, and the various economists' political biases. However, rates of unemployment substantially above 0% have also been attacked by prominent economists, such as John Maynard Keynes:

"The Conservative belief that there is some law of nature which prevents men from being employed, that it is 'rash' to employ men, and that it is financially 'sound' to maintain a tenth of the population in idleness for an indefinite period, is crazily improbable - the sort of thing which no man could believe who had not had his head fuddled with nonsense for years and years. The objections which are raised are mostly not the objections of experience or of practical men. They are based on highly abstract theories – venerable, academic inventions, half misunderstood by those who are applying them today, and based on assumptions which are contrary to the facts… J.M. Keynes, in a pamphlet to support Lloyd George in the 1929 election.

Ideal Unemployment

An alternative, more normative, definition describes full employment as the attainment of the ideal unemployment rate, where the types of unemployment that reflect labor-market inefficiency (such as structural unemployment) do not exist. Only some frictional unemployment would exist, where workers are temporarily searching for new jobs. For example, Lord William Beveridge defined full employment as where the number of unemployed workers equaled the number of job vacancies available. He preferred that the economy be kept above that full employment level in order to allow maximum economic production.

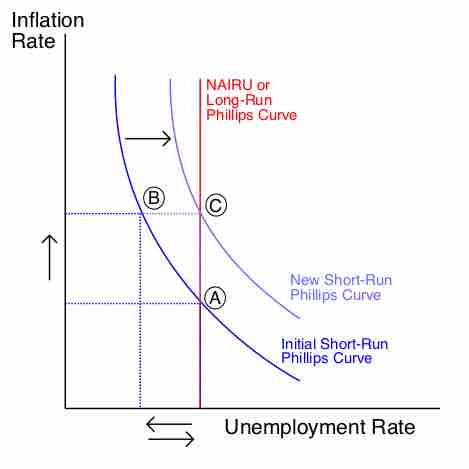

The Phillips curve tells us that there is no single unemployment number that one can single out as the full employment rate. Instead, there is a trade-off between unemployment and inflation: a government might choose to attain a lower unemployment rate but would pay for it with higher inflation rates. Ideas associated with the Phillips curve questioned the possibility and value of full employment in a society: this theory suggests that full employment—especially as defined normatively—will be associated with positive inflation .

NAIRU-SR-and-LR

Short-run Phillips curve before and after Expansionary Policy, with long-run Phillips curve (NAIRU).

There are three important categories of unemployment levels that should be understood in order to evaluate the effect of employment levels on overall economic performance: cyclical unemployment, structural unemployment, and frictional unemployment.

Cyclical Unemployment

Cyclical unemployment occurs when there is not enough aggregate demand in the economy to provide jobs for everyone who wants to work. When demand for most goods and services falls, less production is needed, consequently fewer workers are needed; wages are sticky and do not fall to meet the equilibrium level and mass unemployment results. With cyclical unemployment, the number of unemployed workers exceeds the number of job vacancies, so that even if full employment was attained and all open jobs were filled, some workers would still remain unemployed.

Structural Unemployment

Structural unemployment occurs when a labor market is unable to provide jobs for everyone who wants to work because there is a mismatch between the skills of the unemployed workers and the skills needed for the available jobs. Structural unemployment may be encouraged to rise by persistent cyclical unemployment: if an economy suffers from long-lasting low aggregate demand, many of the unemployed may become disheartened and their skills (including job-searching skills) become rusty and obsolete. The implication is that sustained high demand may lower structural unemployment. Seasonal unemployment may be seen as a kind of structural unemployment, since it is a type of unemployment that is linked to certain kinds of jobs (construction work or migratory farm work).

Frictional Unemployment

Frictional unemployment is the time period between jobs when a worker is searching for or transitioning from one job to another. It is sometimes called search unemployment and can be voluntary based on the circumstances of the unemployed individual. Frictional unemployment is always present in an economy, so the level of involuntary unemployment is properly the unemployment rate minus the rate of frictional unemployment. Frictional unemployment exists because both jobs and workers are heterogeneous, and a mismatch can result between the characteristics of supply and demand. Such a mismatch can be related to any of the following reasons:

- Skills

- Payment

- Work-time

- Location

- Seasonal industries

- Attitude

- Taste

There can be a multitude of other factors, too. New entrants (such as graduating students) and re-entrants (such as former homemakers) can also suffer a spell of frictional unemployment. Workers as well as employers accept a certain level of imperfection, risk, or compromise, but usually not right away; they will invest some time and effort to find a better match. This is in fact beneficial to the economy, since it results in a better allocation of resources.