Spontaneous generation is an obsolete body of thought on the ordinary formation of living organisms without descent from similar organisms. Typically, the idea was that certain forms such as fleas could arise from inanimate matter such as dust or that maggots could arise from dead flesh. A variant idea was that of equivocal generation, in which species such as tapeworms arose from unrelated living organisms, now understood to be their hosts.

Doctrines held that these processes were commonplace and regular. Such ideas were in contradiction to that of univocal generation: effectively exclusive reproduction from genetically related parent(s), generally of the same species. The doctrine of spontaneous generation was coherently synthesized by Aristotle, who compiled and expanded the work of prior natural philosophers and the various ancient explanations of the appearance of organisms; it held sway for two millennia.

Today spontaneous generation is generally accepted to have been decisively dispelled during the 19th century by the experiments of Louis Pasteur. He expanded upon the investigations of predecessors, such as Francesco Redi who, in the 17th century, had performed experiments based on the same principles.

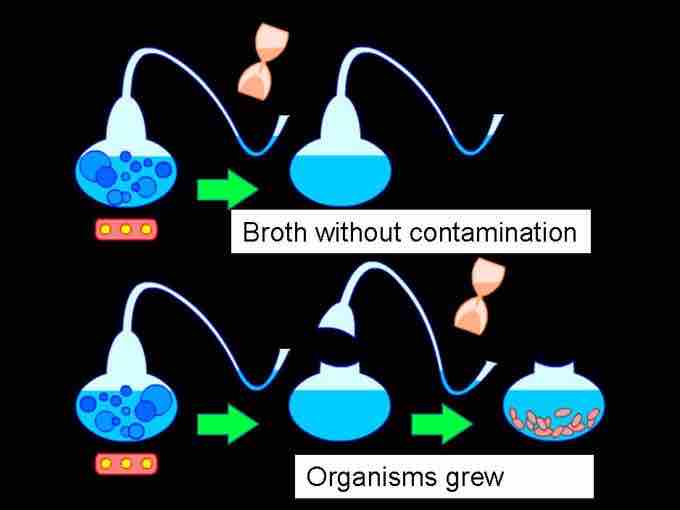

Louis Pasteur's 1859 experiment is widely seen as having settled the question. In summary, Pasteur boiled a meat broth in a flask that had a long neck that curved downward, like a goose. The idea was that the bend in the neck prevented falling particles from reaching the broth, while still allowing the free flow of air. The flask remained free of growth for an extended period. When the flask was turned so that particles could fall down the bends, the broth quickly became clouded . In detail, Pasteur exposed boiled broths to air in vessels that contained a filter to prevent all particles from passing through to the growth medium, and even in vessels with no filter at all, with air being admitted via a long tortuous tube that would not allow dust particles to pass. Nothing grew in the broths unless the flasks were broken open, showing that the living organisms that grew in such broths came from outside, as spores on dust, rather than spontaneously generated within the broth. This was one of the last and most important experiments disproving the theory of spontaneous generation.

Pasteur's test of spontaneous generation.

By sterilizing a food source and keeping it isolated from the outside, Pasteur observed no putrefaction of the food source (top panel). Upon exposure to the outside environment, Pasteur observed the putrefaction of the food source (bottom panel). This strongly suggested that the components needed to create life do not spontaneously arise.

Despite his experiment, objections from persons holding the traditional views persisted. Many of these residual objections were routed by the work of John Tyndall, succeeding the work of Pasteur. Ultimately, the ideas of spontaneous generation were displaced by advances in germ theory and cell theory. Disproof of the traditional ideas of spontaneous generation is no longer controversial among professional biologists. Objections and doubts have been dispelled by studies and documentation of the life cycles of various life forms. However, the principles of the very different matter of the original abiogenesis on this planet — of living from nonliving material — are still under investigation.