In the adult human, the process of defecation is normally a combination of both voluntary and involuntary processes with enough force to remove waste material from the digestive system.

The rectal ampulla acts as a temporary storage facility for the unneeded material. As additional fecal material enters the rectum, the rectal walls expand. A sufficient increase in fecal material in the rectum causes stretch receptors from the nervous system, located in the rectal walls, to trigger the contraction of rectal muscles, relaxation of the internal anal sphincter, and an initial contraction of the skeletal muscle of the external sphincter . The relaxation of the internal anal sphincter causes a signal to be sent to the brain indicating an urge to defecate.

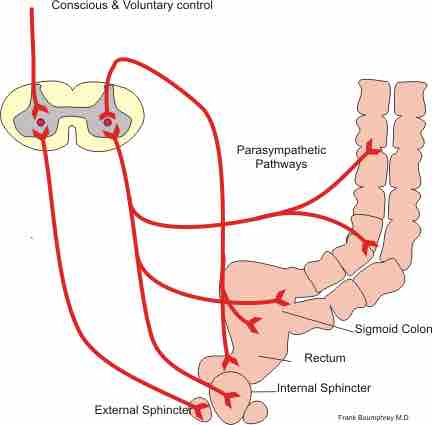

Defecation Reflex

Conscious and parasympathetic pathways of defecation reflex.

If this urge is not acted upon, the material in the rectum is often returned to the colon by reverse peristalsis where more water is absorbed, thus temporarily reducing pressure and stretching within the rectum. The additional fecal material is stored in the colon until the next mass 'peristaltic' movement of the transverse and descending colon. If defecation is delayed for a prolonged period, the fecal matter may harden and autolyze, resulting in constipation.

Once the voluntary signal to defecate is sent back from the brain, the final phase begins. The abdominal muscles contract (straining), causing the intra-abdominal pressure to increase. The perineal wall is lowered, causing the anorectal angle to decrease from 90 degrees to less than 15 degrees (almost straight), and the external anal sphincter relaxes. The rectum now contracts and shortens in peristaltic waves, thus forcing fecal material out of the rectum and out through the anal canal. The internal and external anal sphincters, along with the puborectalis muscle, allow the feces to be passed by pulling the anus up and over the exiting feces in shortening and contracting actions.