The thymus is a specialized organ of the immune system. It consists of primary lymphoid tissue, which provides a site for the generation and maturation of T lymphocytes, critical cells of the adaptive immune system.

Structure of the Thymus

The thymus is of a pinkish-gray color, soft, and lobulated on its surfaces. The organ enlarges during childhood into adolescence and begins to atrophy at puberty due to hormonal changes. After puberty, the thymus shrinks rapidly with age, eventually becoming almost indistinguishable from the surrounding fatty tissue.

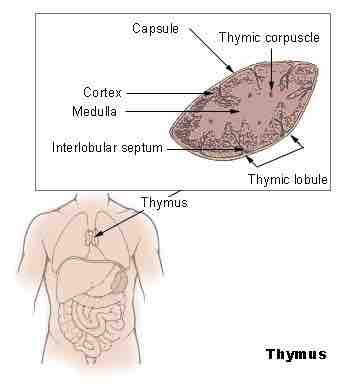

The thymus consists of two lateral lobes placed in close contact along the middle line situated partly in the thorax, resting in the chest beneath the neck. The two lobes differ slightly in size, may be united or separated, and may be broken down into smaller lobules. It is covered with a capsule of connective tissue that provides structural support.

Histologically, the thymus contains mature lymphocytes, immature lymphocytes, and stroma, while lobule tissues consist of an inner medulla and an outer cortex. The cortex and medulla play different roles in the development of T cells. The cortex is the site of T cell generation and proliferation, while the medulla connects to the venous bloodstream and allows for transport of mature inactive T cells to the lymph nodes and transport of immature T cells from bone marrow tissue into the thymus cortex for proliferation and maturation.

Thymus

The thymus is the site of T-cell generation and maturation.

Function of the Thymus

The thymus provides an environment for T cells to mature and proliferate, a process called lymphopoeisis. First, immature T cells generated in bone marrow travel to the cortex tissues of the thymus through the bloodstream. Then the immature T cells undergo proliferative expansion, in which they are exposed to growth factors and antigen receptors are formed. Then the T cells are sorted by the thymus so that only T cells that express T-cell receptors (TcRs) and can bind to foreign MHC molecules will survive. The surviving cells will not mistake self-molecules for antigens. Only 2-4% of T cells survive this sorting process. The thymus is most active early in life for building a large reservoir of T cells. Though removal of the thymus in childhood causes severe immunodeficiency, later in life this is not an issue because of the proliferation of thymus activity early in life.

Central tolerance is another function of the thymus. Autoimmune diseases occur when central tolerance is lost, which causes lymphocytes to recognize host molecules as antigens and attack them, even if those tissues otherwise function normally. The thymus sorts T cells so that they will be inactive towards host molecules, though sometimes a few T cells evade this sorting process and may initiate an autoimmune disease. Though the thymus is mostly effective at preventing this occurrence, those with certain genetic characteristics (such as altered MHC complexes) may be more likely to develop autoimmune diseases with the few T-cells that aren't properly selected by the thymus.