Background

For the first 200 years of United States history, the national policy was isolationism and non-interventionism. George Washington's farewell address is often cited as laying the foundation for a tradition of American non-interventionism: "The great rule of conduct for us, in regard to foreign nations, is in extending our commercial relations, to have with them as little political connection as possible. Europe has a set of primary interests, which to us have none, or a very remote relation. Hence she must be engaged in frequent controversies the causes of which are essentially foreign to our concerns. Hence, therefore, it must be unwise in us to implicate ourselves, by artificial ties, in the ordinary vicissitudes of her politics, or the ordinary combinations and collisions of her friendships or enmities."

No Entangling Alliances in the Nineteenth Century

President Thomas Jefferson extended Washington's ideas in his March 4, 1801 inaugural address: "peace, commerce, and honest friendship with all nations, entangling alliances with none. " Jefferson's phrase "entangling alliances" is, incidentally, sometimes incorrectly attributed to Washington.

Non-interventionism continued throughout the nineteeth century. After Tsar Alexander II put down the 1863 January Uprising in Poland, French Emperor Napoleon III asked the United States to "join in a protest to the Tsar. " Secretary of State William H Seward declined, "defending 'our policy of non-intervention — straight, absolute, and peculiar as it may seem to other nations,'" and insisted that "the American people must be content to recommend the cause of human progress by the wisdom with which they should exercise the powers of self-government, forbearing at all times, and in every way, from foreign alliances, intervention, and interference. "

The United States' policy of non-intervention was maintained throughout most of the nineteenth century. The first significant foreign intervention by the United States was the Spanish-American War, which saw the United States occupy and control the Philipines.

Twentieth Century Non-intervention

Theodore Roosevelt's administration is credited with inciting the Panamanian Revolt against Colombia in order to secure construction rights for the Panama Canal, begun in 1904. President Woodrow Wilson, after winning re-election with the slogan, "He kept us out of war," was nonetheless compelled to declare war on Germany and so involve the nation in World War I when the Zimmerman Telegram was discovered. Yet non-interventionist sentiment remained; the U.S. Congress refused to endorse the Treaty of Versailles or the League of Nations.

Non-Interventionism between the World Wars

In the wake of the First World War, the non-interventionist tendencies of U.S. foreign policy were in full force . First, the United States Congress rejected president Woodrow Wilson's most cherished condition of the Treaty of Versailles, the League of Nations. Many Americans felt that they did not need the rest of the world, and that they were fine making decisions concerning peace on their own. Even though "anti-League" was the policy of the nation, private citizens and lower diplomats either supported or observed the League of Nations. This quasi-isolationism shows that the United States was interested in foreign affairs but was afraid that by pledging full support for the League, it would lose the ability to act on foreign policy as it pleased.

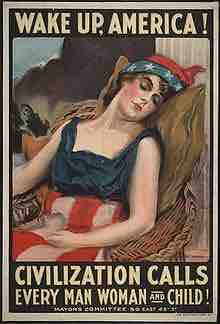

Wake Up America!

At the dawn of WWI, posters like this asked America to abandon its isolationist policies.

Although the United States was unwilling to commit to the League of Nations, they were willing to engage in foreign affairs on their own terms. In August 1928, 15 nations signed the Kellogg-Briand Pact, brainchild of American Secretary of State Frank Kellogg and French Foreign Minister Aristride Briand. This pact that was said to have outlawed war and showed the United States commitment to international peace had its semantic flaws. For example, it did not hold the United States to the conditions of any existing treaties, it still allowed European nations the right to self-defense, and stated that if one nation broke the pact, it would be up to the other signatories to enforce it. The Kellogg-Briand Pact was more of a sign of good intentions on the part of the United States, rather than a legitimate step towards the sustenance of world peace.

Non-interventionism took a new turn after the Crash of 1929. With the economic hysteria, the United States began to focus solely on fixing its economy within its borders and ignored the outside world. As the world's democratic powers were busy fixing their economies within their borders, the fascist powers of Europe and Asia moved their armies into a position to start World War II. With military victory came the spoils of war –a very draconian pummeling of Germany into submission, via the Treaty of Versailles. This near-total humiliation of Germany in the wake of World War I, as the treaty placed sole blame for the war on the nation, laid the groundwork for a pride-hungry German people to embrace Adolf Hitler's rise to power.