Many cultures throughout history have speculated on the nature of the mind, heart, soul, spirit, and brain. Philosophical interest in behavior and the mind dates back to the ancient civilizations of Egypt, Greece, China, and India. Psychology was largely a branch of philosophy until the mid-1800s, when it developed as an independent and scientific discipline in Germany and the United States. These philosophical roots played a large role in the development of the field.

Early Philosophy

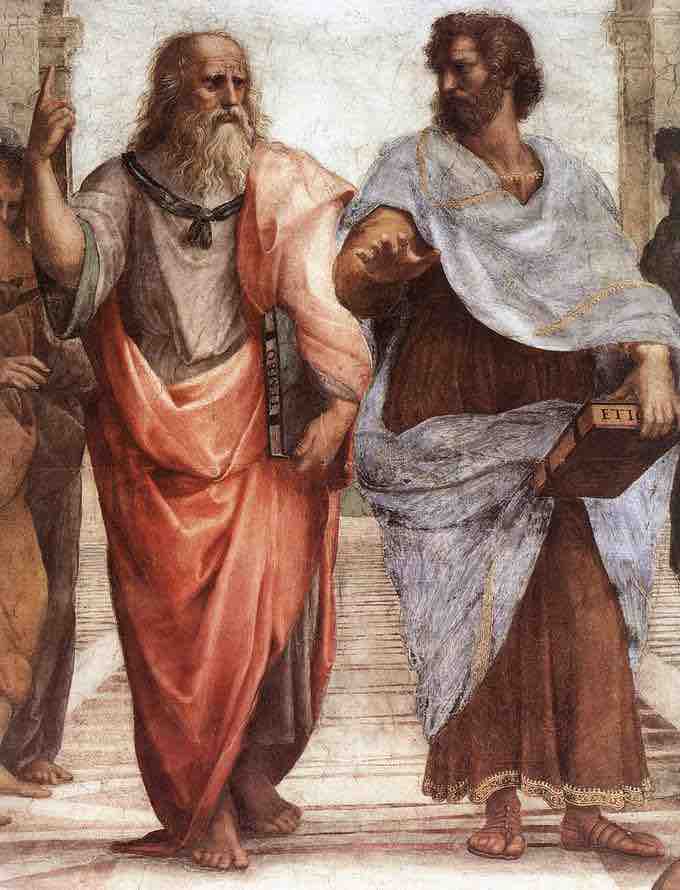

From approximately 600 to 300 BC, Greek philosophers explored a wide range of topics relating to what we now consider psychology. Socrates and his followers, Plato and Aristotle, wrote about such topics as pleasure, pain, knowledge, motivation, and rationality. They theorized about whether human traits are innate or the product of experience, which continues to be a topic of debate in psychology today. They also considered the origins of mental illness, with both Socrates and Plato focusing on psychological forces as the root of such illnesses.

Plato and Aristotle

Plato, Aristotle, and other ancient Greek philosophers examined a wide range of topics relating to what we now consider psychology.

17th Century

René Descartes, a French mathematician and philosopher from the 1600s, theorized that the body and mind are separate entities, a concept that came to be known as dualism. According to dualism, the body is a physical entity with scientifically measurable behavior, while the mind is a spiritual entity that cannot be measured because it transcends the material world. Descartes believed that the two interacted only through a tiny structure at the base of the brain called the pineal gland.

Thomas Hobbes and John Locke were English philosophers from the 17th century who disagreed with the concept of dualism. They argued that all human experiences are physical processes occurring within the brain and nervous system. Thus, their argument was that sensations, images, thoughts, and feelings are all valid subjects of study. As this view holds that the mind and body are one and the same, it later became known as monism. Today, most psychologists reject a rigid dualist position: many years of research indicate that the physical and mental aspects of human experience are deeply intertwined. The fields of psychoneuroimmunology and behavioral medicine explicitly focus on this interconnection.

Psychology as an Independent Discipline

The first use of the term "psychology" is often attributed to the German scholastic philosopher Rudolf Göckel, who published the Psychologia hoc est de hominis perfectione, anima, ortu in 1590. However, the term seems to have been used more than six decades earlier by the Croatian humanist Marko Marulić in the title of his Latin treatise, Psichiologia de ratione animae humanae. The term did not come into popular usage until the German idealist philosopher Christian Wolff used it in his Psychologia empirica and Psychologia rationalis (1732–1734). In England, the term "psychology" overtook "mental philosophy" in the middle of the 19th century.

Wilhelm Wundt

The late 19th century marked the start of psychology as a scientific enterprise. Psychology as a self-conscious field of experimental study began in 1879, when German scientist Wilhelm Wundt founded the first laboratory dedicated exclusively to psychological research in Leipzig. Often considered the father of psychology, Wundt was the first person to refer to himself as a psychologist and wrote the first textbook on psychology, entitled Principles of Physiological Psychology.

Wundt believed that the study of conscious thoughts would be the key to understanding the mind. His approach to the study of the mind was groundbreaking in that it was based on systematic and rigorous observation, laying the foundation for modern psychological experimentation. He systematically studied topics such as attention span, reaction time, vision, emotion, and time perception. Wundt's primary method of research was "introspection," which involves training people to concentrate and report on their conscious experiences as they react to stimuli. This approach is still used today in modern neuroscience research; however, many scientists criticize the use of introspection for its lack of objectivity.

Wilhelm Wundt

Wilhelm Wundt is considered by many to be the founder of psychology. He laid the groundwork for what would later become the theory of structuralism.

Structuralism

Edward B. Titchener, an English professor and a student under Wundt, expanded upon Wundt's ideas and used them to found the theory of structuralism. This theory attempted to understand the mind as the sum of different underlying parts, and focused on three things: (1) the individual elements of consciousness; (2) how these elements are organized into more complex experiences; and (3) how these mental phenomena correlate with physical events.

Titchener attempted to classify the structures of the mind much like the elements of nature are classified in the periodic table—which is not surprising, given that researchers were making great advancements in the field of chemistry during his time. He believed that if the basic components of the mind could be defined and categorized, then the structure of mental processes and higher thinking could be determined. Like Wundt, Titchener used introspection to try to determine the different components of consciousness; however, his method used very strict guidelines for the reporting of an introspective analysis.

Structuralism was criticized because its subject of interest—the conscious experience—was not easily studied with controlled experimentation. Its reliance on introspection, despite Titchener's rigid guidelines, was criticized for its lack of reliability. Critics argued that self-analysis is not feasible, and that introspection could yield different results depending on the subject.

Functionalism

As structuralism struggled to survive the scrutiny of the scientific method, new approaches to studying the mind were sought. One important alternative was functionalism, founded by William James in the late 19th century. Built on structuralism's concern with the anatomy of the mind, functionalism led to greater concern with the functions of the mind, and later, to behaviorism.

Functionalism considers mental life and behavior in terms of active adaptation to the person's environment. James's approach to psychology was less concerned with the composition of the mind and more concerned with examining the ways in which the mind adapts to changing situations and environments. In functionalism, the brain is believed to have evolved for the purpose of bettering the survival chances of its carrier by acting as an information processor: its role is essentially to execute functions similar to the way a computer does.