Eyewitness testimony has been considered a credible source in the past, but its reliability has recently come into question. Research and evidence have shown that memories and individual perceptions are unreliable, often biased, and can be manipulated.

Encoding Issues

Nobody plans to witness a crime; it is not a controlled situation. There are many types of biases and attentional limitations that make it difficult to encode memories during a stressful event.

Time

When witnessing an incident, information about the event is entered into memory. However, the accuracy of this initial information acquisition can be influenced by a number of factors. One factor is the duration of the event being witnessed. In an experiment conducted by Clifford and Richards (1977), participants were instructed to approach police officers and engage in conversation for either 15 or 30 seconds. The experimenter then asked the police officer to recall details of the person to whom they had been speaking (e.g., height, hair color, facial hair, etc.). The results of the study showed that police had significantly more accurate recall of the 30-second conversation group than they did of the 15-second group. This suggests that recall is better for longer events.

Other-Race Effect

The other-race effect (a.k.a., the own-race bias, cross-race effect, other-ethnicity effect, same-race advantage) is one factor thought to affect the accuracy of facial recognition. Studies investigating this effect have shown that a person is better able to recognize faces that match their own race but are less reliable at identifying other races, thus inhibiting encoding. Perception may affect the immediate encoding of these unreliable notions due to prejudices, which can influence the speed of processing and classification of racially ambiguous targets. The ambiguity in eyewitness memory of facial recognition can be attributed to the divergent strategies that are used when under the influence of racial bias.

Weapon-Focus Effect

The weapon-focus effect suggests that the presence of a weapon narrows a person's attention, thus affecting eyewitness memory. A person focuses on a central detail (e.g., a knife) and loses focus on the peripheral details (e.g. the perpetrator's characteristics). While the weapon is remembered clearly, the memories of the other details of the scene suffer. This effect occurs because remembering additional items would require visual attention, which is occupied by the weapon. Therefore, these additional stimuli are frequently not processed.

Retrieval Issues

Trials may take many weeks and require an eyewitness to recall and describe an event many times. These conditions are not ideal for perfect recall; memories can be affected by a number of variables.

Time

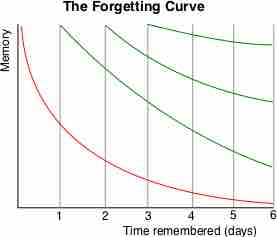

The accuracy of eyewitness memory degrades swiftly after initial encoding. The "forgetting curve" of eyewitness memory shows that memory begins to drop off sharply within 20 minutes following initial encoding, and begins to level off around the second day at a dramatically reduced level of accuracy. Unsurprisingly, research has consistently found that the longer the gap between witnessing and recalling the incident, the less accurately that memory will be recalled. There have been numerous experiments that support this claim. Malpass and Devine (1981) compared the accuracy of witness identifications after 3 days (short retention period) and 5 months (long retention period). The study found no false identifications after the 3-day period, but after 5 months, 35% of identifications were false.

The forgetting curve of memory

The red line shows that eyewitness memory declines rapidly following initial encoding and flattens out after around 2 days at a dramatically reduced level of accuracy.

Leading Questions

In a legal context, the retrieval of information is usually elicited through different types of questioning. A great deal of research has investigated the impact of types of questioning on eyewitness memory, and studies have consistently shown that even very subtle changes in the wording of a question can have an influence. One classic study was conducted in 1974 by Elizabeth Loftus, a notable researcher on the accuracy of memory. In this experiment, participants watched a film of a car accident and were asked to estimate the speed the cars were going when they "contacted" or "smashed" each other. Results showed that just changing this one word influenced the speeds participants estimated: The group that was asked the speed when the cars "contacted" each other gave an average estimate of 31.8 miles per hour, whereas the average speed in the "smashed" condition was 40.8 miles per hour. Age has been shown to impact the accuracy of memory as well. Younger witnesses, especially children, are more susceptible to leading questions and misinformation.

Bias

There are also a number of biases that can alter the accuracy of memory. For instance, racial and gender biases may play into what and how people remember. Likewise, factors that interfere with a witness's ability to get a clear view of the event—like time of day, weather, and poor eyesight—can all lead to false recollections. Finally, the emotional tone of the event can have an impact: for instance, if the event was traumatic, exciting, or just physiologically activating, it will increase adrenaline and other neurochemicals that can damage the accuracy of memory recall.

Memory Conformity

"Memory conformity," also known as social contagion of memory, refers to a situation in which one person's report of a memory influences another person’s report of that same experience. This interference often occurs when individuals discuss what they saw or experienced, and can result in the memories of those involved being influenced by the report of another person. Some factors that contribute to memory conformity are age (the elderly and children are more likely to have memory distortions due to memory conformity) and confidence (individuals are more likely to conform their memories to others if they are not certain about what they remember).