1860 Presidential Election

Historians have long considered the presidential election of 1860 as the immediate impetus for the outbreak of the Civil War. The nation had been divided throughout the 1850s on questions surrounding the expansion of slavery and the rights of slave owners. In 1860, these issues exploded when the Democratic Party officially splintered into Northern and Southern factions, and, in the face of a divided and dispirited opposition, the Republican Party secured enough electoral votes to put Abraham Lincoln in the White House with very little support from the South. Within a few months of the election, seven Southern states, led by South Carolina, responded with declarations of secession.

Conventions and Nominations

By 1860, the Democratic Party had officially split into Northern and Southern factions with tensions erupting in the aftermath of the Dred Scott decision. Southern Democrats resented the Northern Democrats' continued support of popular sovereignty as the best method to determine a territory's free or slave status in spite of Dred Scott. Northern Democrats nominated Stephen A. Douglas of Illinois for president, but Southern Democrats responded by convening separately and nominating John C. Breckinridge of Kentucky as their candidate.

The Republican National Convention met in mid-May. With the Democrats in disarray, and with a sweep of the Northern states possible, the Republicans were confident going into their convention in Chicago. Because it was essential to carry the West, and because Lincoln had a national reputation from previous debates and speeches as the party's most articulate moderate, he won the party's nomination for president on the third ballot on May 18, 1860. The Republican Party platform stated that slavery would not be allowed to spread any further into the territories. The Republicans also promised to support tariffs that protected Northern industry, a Homestead Act granting free farmland in the West to settlers, and the funding of a transcontinental railroad. All of these political issues alienated the South.

Campaign and Results

In the North, there were hundreds of Republican speakers, a deluge of campaign posters and leaflets, and thousands of newspaper editorials. While the campaign propaganda concentrated on disseminating the party platform, it also drew attention to Lincoln's life story, making the most of his boyhood poverty, his pioneer background, his innate genius, and his rise from obscurity. His nicknames, “Honest Abe” and “The Railsplitter,” were exploited to the fullest. The goal was to emphasize the superior power of “free labor,” whereby a common farm boy could work his way to the top by his own efforts and industry. In 1860, many observers noted that the Republicans had an almost unbeatable advantage in the Electoral College because they dominated almost every Northern state.

Lincoln won in the Electoral College with less than 40 percent of the popular vote nationwide, leading contemporaries to cite the split in the Democratic Party as a contributing factor to Lincoln's victory. Like Lincoln in the North, Southern Democrat Breckinridge won no electoral votes outside of the South. He finished second in the Electoral College with 72 votes, carrying 11 of 15 slave states. Douglas was the only candidate to win electoral votes in both the North and the South (in New Jersey and Missouri), but he finished last in the Electoral College.

An Election for Disunion

Although Lincoln and his advisors dismissed Southern alarm over the possibility of Republican victory, many observers recognized that Lincoln's election could result in disunion. Both John Bell of Tennessee (the Constitutional Union Party candidate) and Douglas had campaigned on a platform stating that they could save the Union from secession, warning Americans that a vote for Lincoln was a vote for disunion. Meanwhile, in the South, secessionists threw their support behind Breckinridge in an attempt to contest the election in the House of Representatives (where the selection of president would be made by the representatives elected in 1858), while Southern state military preparations were underway in the event of war.

In 10 of the 11 states that would later declare secession, Lincoln's ticket did not even appear on the ballot; in Virginia, he received only 1 percent of the popular vote. In the four slave states that did not secede (Missouri, Kentucky, Maryland, and Delaware), Lincoln came in third or fourth. Therefore, the 1860 election was not just sectionally divided—it indicated that the South would never accept any Republican candidate who promised to curtail the territorial expansion of slavery. The early nineteenth-century period of compromise and evasion on the slave issue was officially at an end.

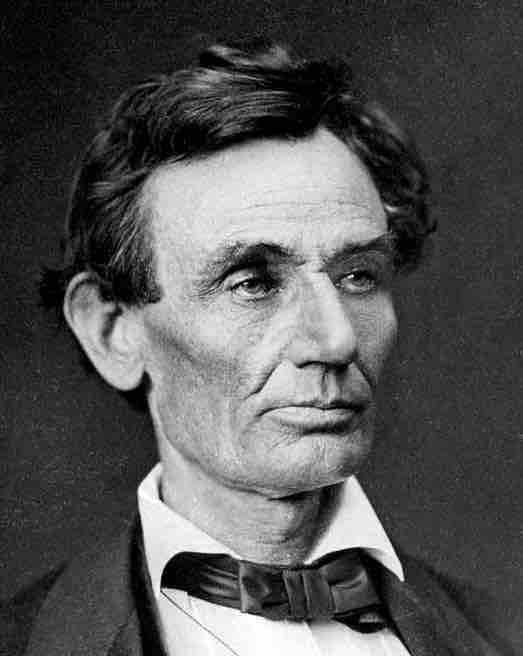

Abraham Lincoln

Lincoln was the Republican candidate for U.S. president in 1860.