Massachusetts Bay

The Massachusetts Bay Colony was an English settlement on the east coast of North America in the 17th century, situated around the present-day cities of Salem and Boston. The territory administered by the colony included parts of what later became the states of Massachusetts, Maine, New Hampshire, Rhode Island, and Connecticut.

Early in the 17th century, several European explorers charted the area. Plans for the first permanent British settlements on the east coast of North America began in late 1606, when King James I of England formed two joint stock companies. The owners of the Massachusetts Bay Company founded the colony. In 1624, the Plymouth Council for New England established a small fishing village at Cape Ann. About 20,000 people migrated to New England in the 1630s, and for the next 10 years, there was a steady exodus of Puritans from England to Massachusetts and the neighboring colonies, a phenomenon now called the Great Migration.

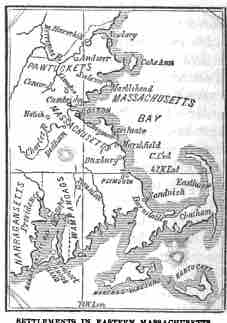

Settlements in Eastern Massachusetts

This map illustrates the early settlements in eastern Massachusetts, including the Massachusetts Bay Colony.

Local Governance

The structure of the colonial government evolved over the lifetime of the charter. The government began with a corporate organization that included a governor and deputy governor, a general court of its shareholders, known as "freemen," and a council of assistants. The council of assistants sat as the upper house of the legislature and served as the judicial court of last appeal. Although its governors were elected, the electorate was limited to freemen, who had been examined for their religious views and formally admitted to their church. As a consequence, the colonial leadership exhibited intolerance to other religious views, including Anglican, Quaker, and Baptist theologies.

Ongoing political difficulties with England after the English Restoration led to the revocation of the colonial charter in 1684 and the brief establishment by King James II of the Dominion of New England in 1686 to bring all of the New England colonies under firmer crown control. The dominion collapsed after the Glorious Revolution of 1688 deposed James, and the colony reverted to rule under the revoked charter until 1692, when the Massachusetts Bay territories combined with those of the Plymouth Colony and proprietary holdings on Nantucket and Martha's Vineyard.

Early Economy and Slavery

The colony's economy began to diversify in the 1640s, as the fur trading, lumber, and fishing industries found markets in Europe and the West Indies and the colony's shipbuilding industry developed. Combined with the growth of a generation of people who were born in the colony, the rise of a merchant class began to slowly change the political and cultural landscape of the colony, though its governance continued to be dominated by relatively conservative Puritans.

Slavery existed but was not widespread within the colony. Some American Indians captured in the Pequot War were enslaved, with those posing the greatest threat being transported to the West Indies and exchanged for goods and slaves. The slave trade, however, became a significant element of the Massachusetts economy in the 18th century as its merchants became increasingly involved in it, transporting slaves from Africa and supplies from New England to the West Indies.

The Role of Women

Some literate Puritan women in the colonies, such as Anne Hutchinson, challenged the male ministers’ authority. Hutchinson's major offense was her claim of direct religious revelation, a type of spiritual experience that negated the role of ministers. Because of Hutchinson’s beliefs and her defiance of authority in the colony, Puritan authorities tried and convicted her of holding false beliefs. In 1638, she was excommunicated and banished from the colony.

Like many other Europeans, the Puritans believed in the supernatural. Every event appeared to be a sign of God’s mercy or judgment, and people believed that witches allied themselves with the Devil to carry out evil deeds and deliberate harm such as the sickness or death of children, the loss of cattle, and other catastrophes. Hundreds were accused of witchcraft in Puritan New England, including townspeople whose habits or appearance bothered their neighbors or who appeared threatening for any reason. Women, seen as more susceptible to the Devil because of their supposedly weaker constitutions, made up the vast majority of suspects and those who were executed. The most notorious cases occurred in Salem Village in 1692.

New Hampshire, Maine, and Connecticut

Two small proprietary colonies were set up in addition to Massachusetts Bay—one in New Hampshire and one in Maine. New Hampshire was not truly a separate province from Massachusetts until after 1691.

Connecticut was formed as a migration from the Massachusetts colony. The original settlements were along the Connecticut River at Hartford, Windsor, and Wethersfield. New Haven was settled separately, but all joined together as Connecticut in 1662. A code of laws was drawn up, beginning with penal laws, which were actually borrowed from the Bible. Like Rhode Island, this colony's history in this century is bound to that of Massachusetts in the Confederation.

Displacement of Algonquians and the Pequot War

Prior to the arrival of Europeans on the eastern shores of New England, the area around Massachusetts Bay was the territory of several Algonquian tribes, including the Massachusett, Nauset, and Wampanoag. The total Algonquian population in 1620 has been estimated to be 7,000. This number was significantly larger as late as 1616; in later years, chroniclers interviewed Algonquians who described a major pestilence brought by Europeans that killed one- to two-thirds of the population.

Although the colonists initially had peaceful relationships with the local Algonquians, frictions arose over cultural differences, which were further exacerbated by Dutch colonial expansion. The Pequot War was the first war between American Indians and English settlers in northeastern America and foreshadowed European domination. Fought in 1637, it was the culmination of numerous conflicts between the colonists and the American Indians. There were disputes over property, livestock that was damaging American Indian crops, hunting, and dishonest traders. Besides these, the colonists believed that they had a God-given right to settle the New World in spite of the centuries-long presence of the American Indians. They saw American Indians as savages who needed to be converted to their way of God, and they continued to feel superior even to those who became Christian.

When the Puritans had initially begun to arrive in the 1620s and 1630s, some local Algonquian peoples had viewed them as potential allies in the conflicts already simmering between rival native groups. In 1621, the Wampanoag, led by Massasoit, concluded a peace treaty with the Pilgrims at Plymouth. In the 1630s, the Puritans in Massachusetts and Plymouth allied themselves with the Narragansett and Mohegan people against the Pequot, who had recently expanded their claims into southern New England.

In May of 1637, the Puritans attacked a large group of several hundred Pequot along the Mystic River in Connecticut. English troops burned the village and killed the estimated 400–700 Pequot inside, massacring all but a handful of the men, women, and children they found. This turned the war against the Pequot and broke the tribe's resistance. The English, supported by Uncas's Mohegan, pursued the remaining Pequot resistors until all were either killed or captured and enslaved. After the war, the colonists enslaved survivors and outlawed the name "Pequot."