Establishing the Carolinas

The Province of Carolina was originally chartered in 1629. In 1663, Charles II of England rewarded eight men for their faithful support of his efforts to regain the throne of England by granting them the land called Carolina; these men were called Lords Proprietors and controlled the Carolinas from 1663 to 1729.

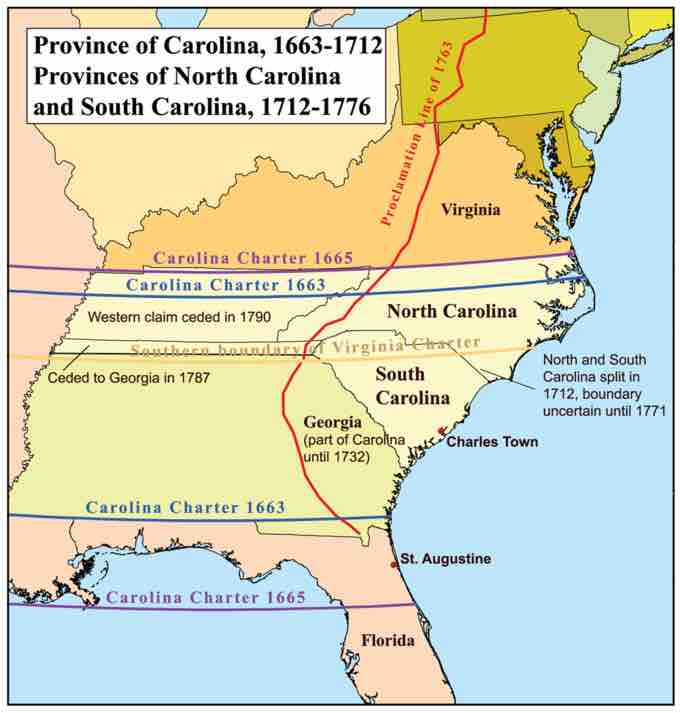

The 1663 charter granted the Lords Proprietor title to all of the land from the southern border of the Virginia Colony to the coast of present-day Georgia. In 1665, the charter was revised slightly, with the northern boundary extended to include the lands of settler-invaders along the Albemarle Sound who had left the Virginia Colony. Likewise, the southern boundary was moved just south of present-day Daytona Beach, Florida, which had the effect of including the existing Spanish settlement at St. Augustine. The charter also granted all the land between these northerly and southerly bounds from the Atlantic Ocean westward to the shores of the Pacific Ocean.

Map of Carolina

A map of the Province of Carolina.

Colonization

Although the Lost Colony on Roanoke Island was the first English attempt at settlement in the Carolina territory, the first permanent English settlement was not established until 1653, when emigrants from the Virginia Colony (with others from New England and Bermuda) settled on the shores of Albemarle Sound in the northeastern corner of present-day North Carolina. The Albemarle Settlements, which preceded the royal charter by 10 years, came to be known in Virginia as "Rogues' Harbor." In 1665, Sir John Yeamans established a second permanent settlement on the Cape Fear River, near present-day Wilmington, North Carolina, which he named Clarendon.

Another region, near present-day Charleston, South Carolina, was settled under the Lords Proprietors in 1670. The Charles Town settlement developed more rapidly than the Albemarle and Cape Fear settlements due to the advantages of a natural harbor, and it quickly developed trade with the West Indies. South Carolina was primarily settled by French Huguenot aristocrats, while North Carolina was settled by poor whites moving in from Virginia.

American Indians

American Indian tribes in the area included the Westos, who lived on the Savannah or Westo River near present day Augusta, as well as Creeks, Shawnees (Savannahs), Cherokees, and Yamasees. Some tribes, such as the Westos, were well armed, using more European weapons than their neighbors at the time. American Indians around Charleston obtained weapons from the Spaniards and from Virginia traders. Carolina, established relatively late, nevertheless soon established an American Indian slave trade that overshadowed other mainland colonies.

As in other areas of English settlement, native peoples in the Carolinas suffered tremendously from the introduction of European diseases. Despite the effects of disease, American Indians in the area endured and, following the pattern elsewhere in the colonies, grew dependent on European goods. Local Yamasee and Creek tribes built up a trade deficit with the English, trading deerskins and captive slaves for European guns. English settlers exacerbated tensions with local American Indian tribes, especially the Yamasee, by expanding their rice and tobacco fields into American Indian lands. Worse still, English traders took American Indian women captive as payment for debts.

The outrages committed by traders, combined with the seemingly unstoppable expansion of English settlement onto native land, led to the outbreak of the Yamasee War (1715–1718), an effort by a coalition of local tribes to drive away the European invaders. This native effort to force the newcomers back across the Atlantic nearly succeeded in annihilating the Carolina colonies. Only when the Cherokee allied themselves with the English did the coalition’s goal of eliminating the English from the region falter.

Agriculture and Economy

As the settlement around Charles Town grew, it began to produce livestock for export to the West Indies. In the northern part of Carolina, settlers turned sap from pine trees into turpentine used to waterproof wooden ships. The southern part of Carolina had been producing rice and indigo (a plant that yields a dark blue dye used by English royalty) since the 1700s, and South Carolina continued to depend on these main crops. The northern part of Carolina continued to produce items for ships, especially turpentine and tar, and its population increased as Virginians moved there to expand their tobacco holdings. Tobacco was the primary export of both Virginia and later North Carolina, which also traded in deerskins and slaves from Africa.

Slavery developed quickly in the Carolinas, largely because so many of the early migrants came from Barbados, where slavery was well established. By the end of the 1600s, a very wealthy class of rice planters who relied on slaves had attained dominance in the southern part of the Carolinas, especially around Charles Town. By 1715, the southern part of Carolina had a black majority because of the number of slaves in the colony. The legal basis for slavery was established in the early 1700s as the Carolinas began to pass slave laws based on the Barbados slave codes of the late 1600s. These laws reduced Africans to the status of property to be bought and sold as other commodities.

Government

The Lords Proprietors, operating under their royal charter, were able to exercise their authority with nearly the autonomy of the king himself. One of the Lords Proprietors, Anthony Ashley Cooper, 1st Earl of Shaftesbury (with the assistance of his secretary, the philosopher John Locke), drafted the Fundamental Constitutions of Carolina, a plan for government. The actual government consisted of a governor, a powerful council (of which half of the members were appointed by the Lords Proprietors themselves), and a relatively weak, popularly elected assembly.

Division of North and South Carolina

The Charleston settlement was the principal seat of government for the entire province. However, due to their remoteness from each other, the northern and southern sections of the colony operated more or less independently until 1691, when dissent over the governance of the province led to the appointment of a deputy governor to administer the northern half of Carolina. From that time until 1708, the northern and southern settlements remained under one government. The north continued to have its own assembly and council; the governor resided in Charleston and appointed a deputy governor for the north. During this period, the two halves of the province began increasingly to be known as North Carolina and South Carolina.

From 1708 to 1710, due to disquiet over attempts to establish the Anglican Church in the province, the people were unable to agree on a slate of elected officials. Consequently, there was no recognized and legal government for more than two years. This period culminated in Cary's Rebellion when the Lords Proprietors finally commissioned a new governor. This circumstance, coupled with hostilities with American Indian tribes and the inability of the Lords Proprietors to act decisively, led to separate governments for North and South Carolina.

The division between the northern and southern governments became complete in 1712, but both colonies remained in the hands of the same group of proprietors. Another rebellion against the proprietors broke out in 1719, which led to the appointment of a royal governor for South Carolina in 1720. After nearly a decade in which the British government sought to locate and buy out the proprietors, both North and South Carolina became royal colonies in 1729 when seven of the Lords Proprietors sold their interests in Carolina to the Crown.