Overview: Slavery in South Carolina

South Carolina, later dubbed the "Rice Kingdom," was one of the first North American colonies to be deliberately founded on slave labor. In the 17th century, wealthy planters from Barbados, accompanied by their African slaves, immigrated to South Carolina looking for arable lands. The planters were well aware that African slaves had skills and attributes well suited to the semi-tropical environment of South Carolina. Hence, South Carolinian planters began importing Africans in large numbers, and in 1710, African-born slaves outnumbered American-born people. By 1720, South Carolina's population was 65% enslaved. Wealthy planters cultivated rice and other cash crops along the southeastern coast, while backwoods subsistence farmers were pushed out to the Appalachian Mountains and backcountry in the later part of the 18th century. These backcountry farmers, like their counterparts in the Chesapeake, seldom owned slaves.

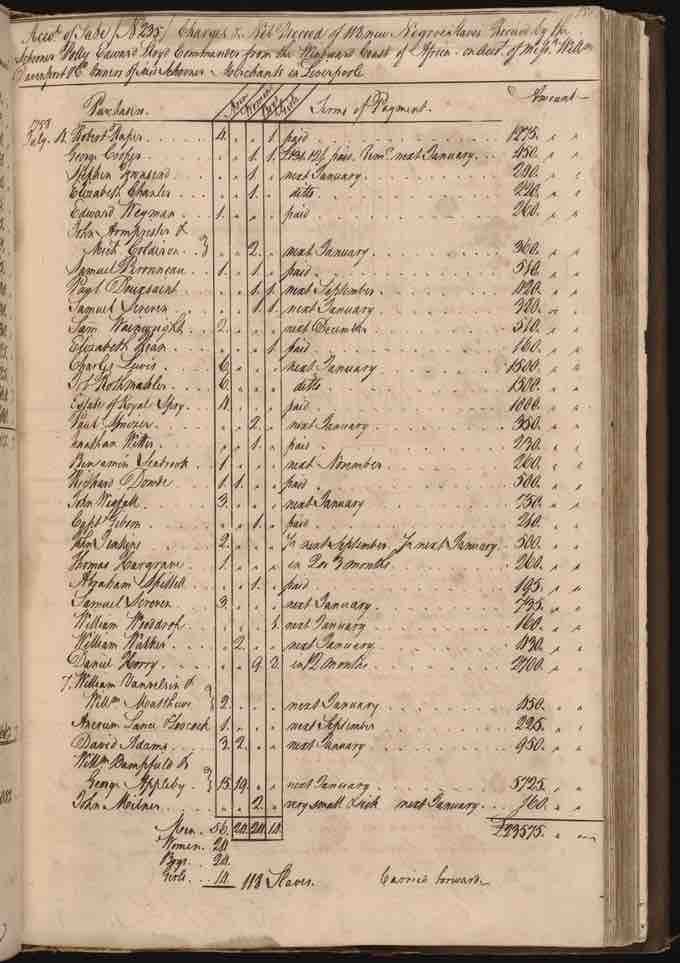

Ledger of sale in South Carolina

Ledger of sale of 118 slaves, Charleston, South Carolina, c. 1754.

The Rice Economy and the Role of Slavery

The principle cash crop harvested by the South Carolina slave population in the early 18th century was rice, a crop which probably originated in Madagascar and had been introduced into South Carolina in 1694. Once rice was established as the principle cash crop of South Carolina, it brought unprecedented wealth and prosperity to planters and the region. By 1850, a South Carolinian rice planter, Joshua John Ward, was the largest American slaveholder, with an estate that held 1,130 slaves and gave him the title, "King of the Rice Planters."

It is no coincidence that white planters in the region starting importing African slaves when rice cultivation was introduced into the South, as the first English planters in South Carolina knew little about rice cultivation. The planters relied on the expertise of their African slaves imported from the Rice Coast. For instance, enslaved Africans showed planters how to properly dyke the marshes, periodically flood the rice fields, and use sweetgrass baskets for milling the rice quicker than wooden paddles. These innovations increased the efficiency and profitability of cultivation. In later years, water-powered mills, designed by millwright Jonathan Lucas, also helped expand rice cultivation in the South. Rice plantations were larger than their tobacco counterparts in the Chesapeake, and planters expected slaves to cultivate up to five acres of rice a year, in addition to growing their own vegetables to feed themselves and their families.

Rice cultivation in the southeastern United States became less profitable with the loss of slave labor after the American Civil War, and it finally died out just after the turn of the 20th century.

The Old Plantation, c. 1790

Painting of slaves on a South Carolina plantation