Overview

Following the Battle of Bunker Hill in June 1775, Patriots had gained control of most of Massachusetts. In a sudden shift, the Loyalists found themselves on the defensive. In all 13 colonies, Patriots had overthrown their existing governments, closing courts and driving British governors, agents, and supporters from their homes. They had also elected conventions and "legislatures" that existed outside of any currently established legal framework. New constitutions were used in each colony to supersede royal charters, and the colonies declared themselves states.

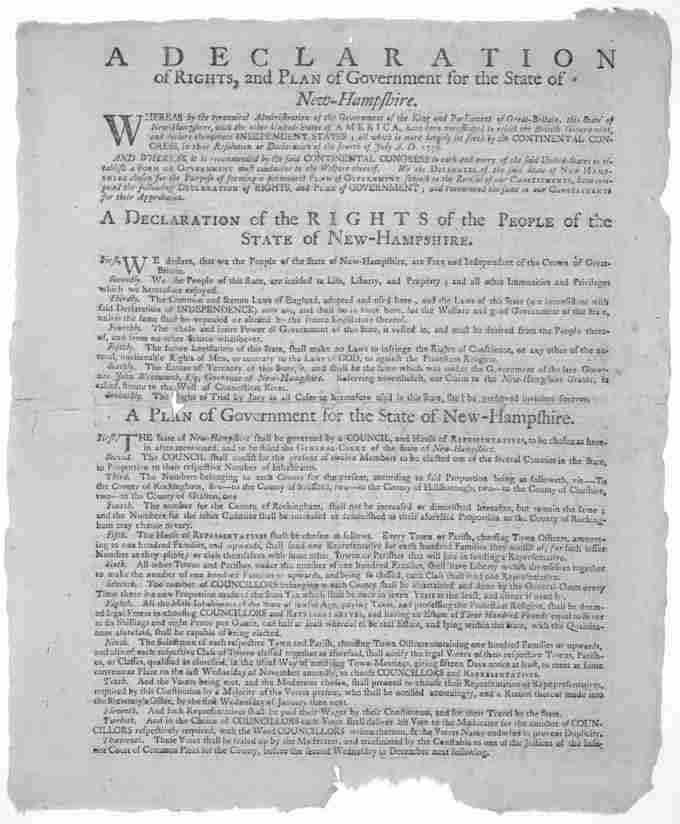

On January 5, 1776, New Hampshire ratified the first state constitution, 6 months before the Declaration of Independence was signed. In May 1776, Congress voted to suppress all forms of crown authority and replace them with locally created authority. Virginia, South Carolina, and New Jersey created their constitutions before July 4. Rhode Island and Connecticut simply took their existing royal charters and deleted all references to the crown.

State Constitutions

The new states had to decide what form of government to create, how to select those who would craft the constitutions, and how the resulting document would be ratified. Key differences existed between the respective documents drafted by affluent and less affluent states. In states where the wealthy exerted firm control over the process (such as Maryland, Virginia, Delaware, New York, and Massachusetts) the resulting constitutions featured:

- Substantial property qualifications for voting and even more substantial requirements for elected positions (though New York and Maryland lowered property qualifications)

- Bicameral legislatures, with the upper house serving as a check on the lower

- Strong governors with veto power over the legislature and substantial appointment authority

- Few or no restraints on individuals holding multiple positions in government

- Continuation of state-established religion

In states where the less-affluent had organized sufficiently to acquire significant power—especially Pennsylvania, New Jersey, and New Hampshire—the resulting constitutions often contained:

- Relatively weak governors without veto powers and little appointing authority

- Universal white male suffrage, or minimal property requirements for voting or holding office (New Jersey enfranchised some property-owning widows, a step it retracted 25 years later)

- Strong, unicameral legislatures

- Prohibition against individuals holding multiple government posts

Regardless of whether conservatives or radicals held sway in a state, the side with less power did not accept the result quietly. For example, the radical provisions of Pennsylvania's constitution lasted only 14 years. In 1790, conservatives gained power in the state legislature, called for a new constitutional convention, and rewrote the constitution. The new constitution substantially reduced universal white-male suffrage, gave the governor veto power and patronage appointment authority, and added to the unicameral legislature an upper house with substantial wealth qualifications.

New Hampshire's Constitution

The Declaration of Rights and Plan of Government for the State of New Hampshire. New Hampshire was the first state to create a new constitution, in 1776, at the urging of the Continental Congress.

Relationship to the Confederation Congress

While the state constitutions were being created, the Continental Congress continued to meet as a general political body. Despite its being the central government, it was a loose confederation, and the individual states help most significant power. Even with the Articles of Confederation, the central government's power was quite limited. While Congress could call on states to contribute money, specific resources, and numbers of men needed for the army, it was not allowed to force states to obey the central government's requests.