Background

During the Reconstruction period of 1865–1877, federal law provided civil rights protection in the U.S. South for freedmen, the African Americans who had formerly been slaves. In the 1870s, Democrats gradually returned to power in the Southern states, sometimes as a result of elections in which paramilitary groups intimidated opponents, attacking blacks or preventing them from voting. Gubernatorial elections were close and disputed in Louisiana for years, with extreme violence being unleashed during the campaigns. In 1877, a national compromise to gain Southern support in the presidential election resulted in the last of the federal troops being withdrawn from the South. White Democrats had regained political power in every Southern state. These conservative, white, Democratic Redeemer governments legislated Jim Crow laws, which segregated black people from the white population, and upheld them constitutionally as "separate but equal" rights.

Federal Aid

The federal government adopted a policy of providing arable land to former black slaves during the last stages of the American Civil War in 1865. They were freed as a result of the advance of the Union armies into the territory previously controlled by the Confederacy, particularly after Major General William Tecumseh Sherman's March to the Sea. General Sherman's Special Field Orders, No. 15, issued on January 16, 1865, provided for the land, while some of its beneficiaries also received mules from the army for plowing. The policy became known as "forty acres and a mule."

The Special Field Orders issued by Sherman were never intended to represent an official policy of the U.S. government with regard to all former slaves. Andrew Johnson, who succeeded President Lincoln after the assassination, revoked Sherman's orders and returned the land to its previous white owners. Because of this, the phrase "forty acres and a mule" has come to represent the failure of Reconstruction policies in restoring to African Americans the fruits of their labor.

During this time, the federal government also attempted to provide aid to black Southerners through the Freedmen's Bureau. The bureau was created through the Freedmen's Bureau Bill, which was initiated by President Abraham Lincoln, and was intended to last for one year after the end of the Civil War. On March 3, 1865, Congress passed the bill to aid former slaves through legal food and housing, oversight, education, health care, and employment contracts with private landowners.

At the end of the war, the Freemen's Bureau's main role was providing emergency food, housing, and medical aid to refugees; it also helped reunite families. Later, it focused its work on helping the freedmen adjust to their condition of freedom by setting up work opportunities and supervising labor contracts. It soon became, in effect, a military court that handled legal issues. The bureau distributed 15 million rations of food to African Americans, and set up a system in which planters could borrow rations in order to feed freedmen they employed.

The most widely recognized of the Freedmen's Bureau's achievements is its accomplishments in the field of education. Prior to the Civil War, no Southern state had a system of universal state-supported public education. Freedmen had a strong desire to learn to read and write. They had worked hard to establish schools in their communities prior to the advent of the Freedmen's Bureau. By 1866, missionary and aid societies worked in conjunction with the Freedmen's Bureau to provide education for former slaves.

The bureau faced many challenges despite its good intentions, efforts, and limited successes. By 1866, it was attacked by Southern whites for organizing blacks against their former masters. That same year President Andrew Johnson, supported by Radical Republicans, vetoed a bill for an increase of power for the bureau. Many local bureau agents were hindered in carrying out their duties by the opposition of former Confederates, and lacked a military presence to enforce their authority.

Black Disfranchisement

Jim Crow laws were state and local laws enforcing racial segregation in the Southern United States. Many of these laws were focused on legally disfranchising the freedmen, especially with regard to voting, thereby blocking their participation in political life. Blacks were still elected to local offices in the 1880s, but the establishment Democrats were passing laws to make voter registration and electoral rules more restrictive. As a result, political participation by most blacks and many poor whites began to decrease. Between 1890 and 1910, 10 of the 11 former Confederate states, starting with Mississippi, passed new constitutions or amendments that effectively disfranchised most blacks and tens of thousands of poor whites through a combination of poll taxes, literacy and comprehension tests, and residency and record-keeping requirements. Grandfather clauses temporarily permitted some illiterate whites to vote.

Those who could not vote were not eligible to serve on juries and could not run for local offices. They effectively disappeared from political life, as they could not influence the state legislatures, and their interests were overlooked. Public schools had been established by Reconstruction legislatures for the first time in most Southern states. The schools for black children were consistently underfunded compared to schools for white children, even when considered within the strained finances of the postwar South. The decreasing price of cotton kept the agricultural economy at a low.

White supremacist paramilitary organizations, allied with Southern Democrats, used intimidation, violence, and assassinations to repress blacks and prevent them from exercising their civil rights in elections from 1868 until the mid-1870s. The insurgent Ku Klux Klan (KKK) was formed in 1865 in Tennessee (as a backlash to defeat in the war) and quickly became a powerful secret vigilante group, with chapters across the South. The Klan initiated a campaign of intimidation directed against blacks and sympathetic whites. Their violence included vandalism and destruction of property, physical attacks and assassinations, and lynchings. Teachers who came from the North to teach freedmen were sometimes attacked or intimidated as well.

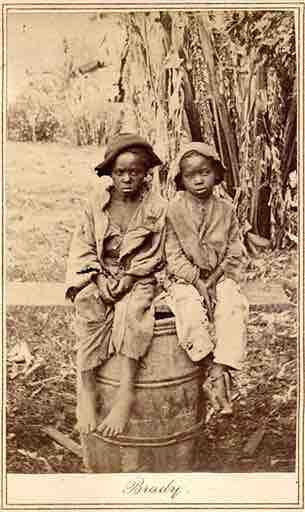

Slave children

Two children who were likely emancipated during the Civil War, circa 1870.