Introduction: Higher Education in the United States

During the nineteenth century, the nation's many small colleges helped young men make the transition from rural farms to complex urban occupations. These colleges prepared ministers and provided towns across the country with a core of community leaders. The more elite colleges became increasingly exclusive and contributed relatively little toward upward social mobility. By concentrating on the offspring of wealthy families, ministers, and a few others, prestigious eastern colleges, especially Harvard, played an important role in the formation of a northeastern elite with great power.

Morrill Land-Grant College Act

The Morrill Land-Grant College Act was a U.S. statute signed into law by President Abraham Lincoln on July 2, 1862, that allowed for the creation of land-grant colleges. For 20 years prior to the first introduction of the bill in 1857, a political movement, led by Professor Jonathan Baldwin Turner of Illinois College, called for the creation of agriculture colleges. On February 8, 1853, the Illinois Legislature adopted a resolution, drafted by Turner, calling for the Illinois congressional delegation to work to enact a land-grant bill to fund a system of industrial colleges in every state.

The Morrill Act was first proposed in 1857 and was passed by Congress in 1859. However, it was vetoed by President James Buchanan. In 1861, Morrill resubmitted the act with the amendment that the proposed institutions would teach military tactics as well as engineering and agriculture. Aided by the secession of many states that did not support the plans, this reconfigured Morrill Act was signed into law by President Abraham Lincoln in 1862.

The purpose of the land-grant colleges was:

... without excluding other scientific and classical studies and including military tactic, to teach such branches of learning as are related to agriculture and the mechanic arts, in such manner as the legislatures of the States may respectively prescribe, in order to promote the liberal and practical education of the industrial classes in the several pursuits and professions in life.

Under the act, each eligible state received a total of 30,000 acres of federal land, either within or contiguous to its boundaries, for each member of Congress held by the state. This land, or the proceeds from its sale, was to be used toward establishing and funding the educational institutions described above. In reference to the recent secession of several Southern states and the currently raging American Civil War, the Act stipulated that, "No State while in a condition of rebellion or insurrection against the government of the United States shall be entitled to the benefit of this act." After the war, however, the 1862 Act was extended to the former Confederate states; it was eventually extended to every state and territory, including those created after 1862.

If the federal land within a state was insufficient to meet that state's land grant, the state was issued "scrip," which authorized the state to select federal lands in other states to fund its institution. For example, New York carefully selected valuable timber land in Wisconsin to fund Cornell University. The 1862 Morrill Act allocated a total of 17.4 million acres of land, which, when sold, yielded a collective endowment of $7.55 million. The state of Iowa was the first to accept the terms of the Morrill Act, which provided the funding boost needed for the fledgling Ames College (now Iowa State University). With a few exceptions, including Cornell University and the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, nearly all of the Land-Grant Colleges are public. Cornell University, while private, administers several state-supported contract colleges that fulfill its public land-grant mission to the state of New York.

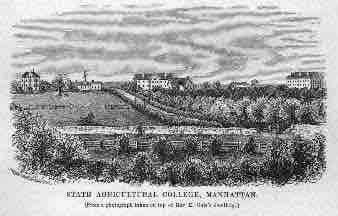

Kansas State University, 1878

Kansas State University was the first college funded by land grants under the Morrill Act of 1862.

The land-grant college system produced the agricultural scientists and industrial engineers who were critical to the managerial revolution in government and business of 1862–1917, and laid the foundation for a preeminent educational infrastructure that supported the world's foremost technology-based economy.

The Farmers' High School of Pennsylvania

The Farmers' High School of Pennsylvania (later the Agricultural College of Pennsylvania and then Pennsylvania State University), chartered in 1855, was intended to uphold declining agrarian values and show farmers ways to prosper through more productive farming. Students were to build character and meet a part of their expenses by performing agricultural labor. By 1875, the compulsory labor requirement was dropped, but male students were to have an hour a day of military training in order to meet the requirements of the Morrill Land-Grant College Act. In the early years, the agricultural curriculum was not well developed, and politicians in Harrisburg often considered it a costly and useless experiment. The college was a center of middle-class values that served to help young people on their journey to white-collar occupations.

The Second Morrill Act of 1890

A second Morrill Act was later introduced in 1890 that required each state to show that race was not an admissions criterion, or else to designate a separate land-grant institution for persons of color. Among the 70 colleges and universities that eventually evolved from the Morrill Acts are several of today's "Historically Black Colleges and Universities" (HBCUs).