Immigrant Labor

Immigrants of the nineteenth century flocked to urban destinations, making up the bulk of the U.S. industrial labor pool. These new sources of labor profoundly influenced the emergence of the steel, coal, automobile, textile, and garment industries, increasing production and enabling the United States to leap into the front ranks of the world's economies.

Many of the population and economic gains during the nineteenth century were made possible by immigration, as hundreds of thousands of people came from Europe, China, and Latin America seeking the job opportunities and the perceived prospect of a better life in America. Different immigrant groups tended to drift toward different occupations, depending on their background. The Irish provided mostly unskilled labor in factories, textile mills, and large infrastructure projects such as canals and railroads. Many Irish went to the emerging textile mill towns of the Northeast, while others became longshoremen in the growing Atlantic and Gulf port cities. Roughly half of the immigrants from Germany went to farms, especially in the Midwest and Texas, while the other half became craftsmen and entrepreneurs in urban areas.

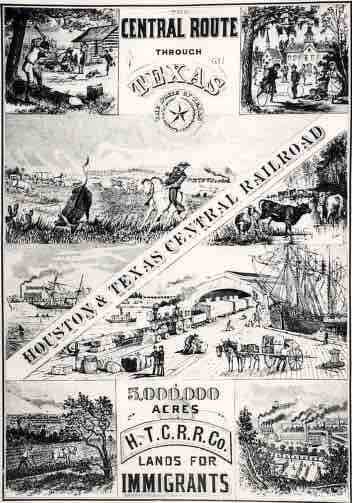

Poster by the Houston and Texas Railroad advertising land for immigrants

Many immigrants were attracted to the United States by the availability of cheap farmland. In particular, large numbers of German immigrants became farmers in the United States.

The California Gold Rush

In 1849, the California gold rush brought in more than 100,000 would-be miners from the eastern United States, Latin America, China, Australia, and Europe. California became a state in 1850 with a population of about 90,000. Many of the immigrants who came for the gold rush also stayed to work on large infrastructure projects such as the railroads.

Exploitation and Discrimination

As German and Irish immigrants poured into the United States in the decades preceding the Civil War, native-born laborers found themselves competing for jobs with new arrivals who were more likely to work longer hours for less pay. In Lowell, Massachusetts, for example, the daughters of New England farmers encountered competition from the daughters of Irish farmers suffering the effects of the potato famine; these immigrant women were willing to work for far less and endure worse conditions than native-born women. Male German and Irish immigrants also competed with native-born men. Germans, many of whom were skilled workers, took jobs in furniture making. The Irish provided a ready source of unskilled labor needed to lay railroad tracks and dig canals.

American men with families to support grudgingly accepted low wages in order to keep their jobs. As work became increasingly deskilled, no worker was irreplaceable, and no one’s job was safe. The resulting competition over jobs led to increased hostility from many native-born Americans toward immigrants during the nineteenth century.