The Rise of the Temperance Movement

In the late eighteenth century, the early temperance movement sparked to life with Benjamin Rush's 1784 tract, "An Inquiry Into the Effects of Ardent Spirits Upon the Human Body and Mind," which judged the excessive use of alcohol as injurious to physical and psychological health. Influenced by this inquiry, about 200 farmers in a Connecticut community formed a temperance association in 1789 to ban the making of whiskey. Similar associations formed in Virginia in 1800 and New York in 1808.

Over the next decade, other temperance organizations formed in eight states, some of which were state-wide. Economic change and urbanization in the early nineteenth century were accompanied by increasing poverty, and various factors contributed to a widespread increase in alcohol use. Advocates for temperance argued that such alcohol use went hand in hand with spousal abuse, family neglect, and chronic unemployment. Americans increasingly drank more strong, cheap alcoholic beverages such as rum and whiskey, and pressure for inexpensive and plentiful alcohol led to relaxed ordinances on alcohol sales, which temperance advocates sought to reform.

The movement advocated temperance, or levelness, rather than abstinence. Many leaders of the movement expanded their activities and took positions on observance of the Sabbath and other moral issues. The reform movements met with resistance from brewers and distillers; many business owners were even fearful of women having the right to vote because it was expected that they would tend to vote for temperance.

Some leaders persevered in pressing their cause forward. Americans such as Lyman Beecher, a Connecticut minister, had started to lecture fellow citizens against all use of liquor in 1825. The American Temperance Society was formed in 1826 and benefited from a renewed interest in religion and morality. Within 12 years it claimed more than 8,000 local groups and more than 1,500,000 members. By 1839, 18 temperance journals were being published. Simultaneously, some Protestant and Catholic church leaders were beginning to promote temperance.

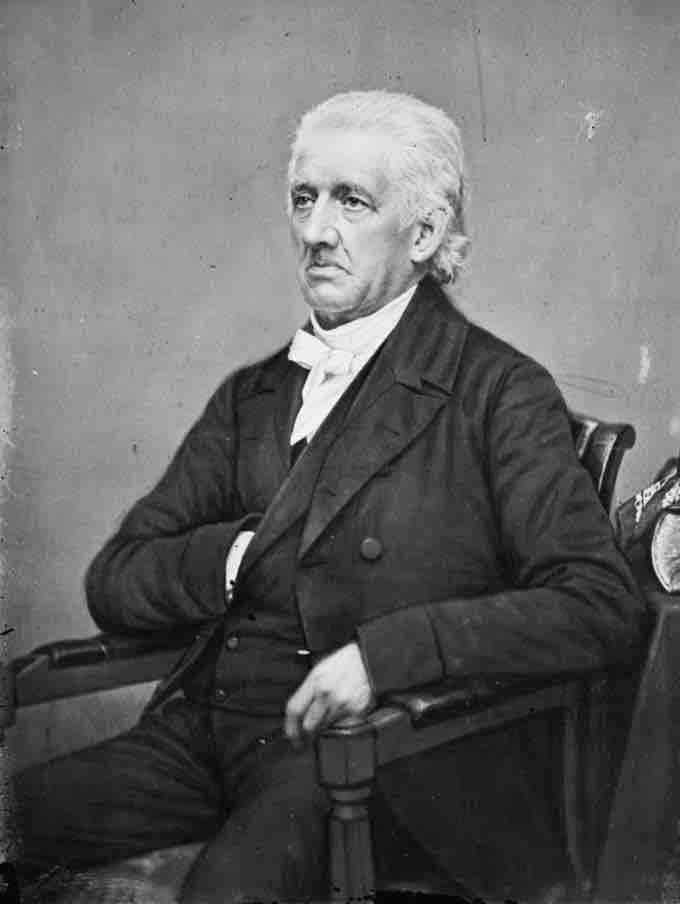

Lyman Beecher, ca. 1855

Lyman Beecher was a charismatic and influential preacher during the first half of the nineteenth century who championed, among other moral reforms, the temperance movement.

The movement split along two lines in the late 1830s between moderates, who allowed some drinking, and radicals, who demanded total abstinence. A split also formed between voluntarists, who relied on moral persuasion alone, and prohibitionists, who promoted laws to restrict or ban alcohol. Radicals and prohibitionists dominated many of the largest temperance organizations after the 1830s, and temperance eventually became synonymous with prohibition.

Temperance in Popular Culture

The movement gained momentum to the point that it inspired an entire genre of theatre. This was first seen in 1825, as The Forgers, a dramatic poem written by John Blake White, premiered at the Charleston Theatre in Charleston, South Carolina. The next significant temperance drama to debut was titled Fifteen Years of a Drunkard's Life, written by Douglas Jerrold in 1841. As the movement began to grow and prosper, these dramas became more popular among the general public. The Drunkard by W. H. Smith premiered in 1841 in Boston, running for 144 performances before being produced at P.T. Barnum's American Museum on lower Broadway. The play was wildly popular and is often credited with the entrance of the temperance narrative into mainstream American theatre. It continued to be a staple of New York's theatre scene until 1875. The Drunkard follows the typical format of a temperance drama: The main character has an alcohol-induced downfall, and he restores his life from disarray after he denounces drinking for good at the play's end.

Temperance and the Civil War

The Civil War dealt the movement a crippling blow. Temperance groups in the South were weaker than their northern counterparts and too voluntarist to gain any statewide prohibition law, and the few prohibition laws in the North were repealed by the war's end. Both sides in the war made alcohol sales a part of the war effort by taxing brewers and distillers to finance much of the conflict. The issue of slavery crowded out the argument about temperance, and temperance groups largely fell by the wayside until they found new life in the 1870s.